Technology is disrupting business models and markets—and the responsibilities of many corporate boards. To fulfill their oversight role, boards need to ensure that a growing array of IT risks and projects are being well managed. At the same time, they need to understand how technology can help attain and sustain competitive advantage. The upshot is that boards need to know much more about IT—a tall order for directors who often don’t “speak the language.”

To be sure, some boards have sensed the shift and have created a governance mechanism—such as a technology committee—to keep pace and ensure that the next data breach doesn’t happen on their watch. But even if a board has implemented such a structure, directors still need to have an understanding of the organization’s IT, including the risks and potential. Critical to this understanding is having the right amount of detail and context.

Tackling this challenge isn’t easy, but there is a person who is uniquely qualified to help: the CIO. A company’s CIO can help the board assess not only IT risks and regulatory compliance but also the strategic value that technology can add.

A Three-Point Plan

Technology doesn’t play the same role in every company or take on the same degree of importance. Accordingly, different boards need to provide different levels of IT governance.

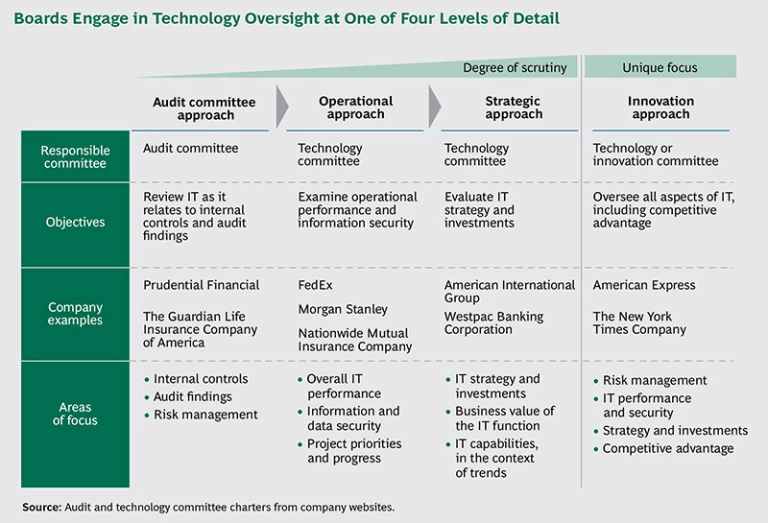

Consider the various approaches boards are currently taking toward IT oversight. Most still focus on internal controls and risk, and the audit committee steers the effort. But some boards have moved to an operational approach, creating technology committees that examine overall IT operational performance and information security, as well as project priorities and progress. Less frequently, boards are adopting a strategic approach, establishing a technology committee to evaluate the company’s IT strategy and investments, as well as the business value of the IT function. Finally, the boards of a global financial-services company and a large media organization have gone further still, tasking their technology or “innovation” committee, as it is sometimes called, with reviewing IT as it relates to competitive advantage, in addition to overseeing risk, operations, and strategy. (See the exhibit below.)

No matter which approach a board takes, CIOs can help directors home in on and better understand the IT issues—and solutions—most relevant to the business. CIOs do this by providing information on and the context for technology and concerns. Like most people who are not technical experts, directors often have misconceptions about IT. Security breaches, for example, are often blamed on faulty technology. In fact, many breaches aren’t rooted so much in IT as they are in processes and people. CIOs can help boards by shedding light on the circumstances and conditions that lead up to such events.

The three strategies we present here enable CIOs to engage with their board, reducing the mystery, misgivings, and misconceptions surrounding technology and helping directors understand and evaluate what really matters when it comes to the company’s IT.

Take the lead on shaping the board’s IT conversation. Instead of waiting for the board to ask for reports and updates, CIOs should initiate and steer the conversation. This doesn’t mean delving into a full array of technology topics with every director. Rather, CIOs should carefully choose the issues to discuss and the sequence in which to present them, so as to gradually build directors’ comfort and knowledge with the topics.

How should CIOs choose the issues? Clearly, the focus should be on IT topics that are most relevant to the business—a list that the CIO should develop with input from the CEO. Collaborating with the chief executive is a crucial first step; CIOs can lock down important topics and avoid conflicts with someone who can be a powerful ally and facilitate access to the board.

The CEO can also help identify board members who have a technology background or a heightened interest in IT oversight—such as the chair of an audit committee. These directors are important stakeholders for the CIO. They can prove valuable partners when engaging with the rest of the board and, as such, should be a first point of contact. These directors also have a feel for the board’s IT concerns, as well as its level of technical sophistication. And these directors can act as a sounding board for presentations before the CIO speaks to the full board.

Indeed, board presentations can be tricky. They need to be tailored to the board’s level of “IT savviness,” striking the right balance between educating and informing, but they also must be compelling. The benefits and the business cases should be clear. Any examples should resonate. Drawing on how directors use technology in their own lives can make IT personal. To ensure a successful presentation, CIOs may want to consider taking a media-training course or having professional marketing or communications talent to call on when creating and giving a presentation. These individuals can greatly enhance a CIOs ability to “make it real” for the board.

Assume the role of technology advisor. CIOs should look for ways to build a rapport with and earn the trust of the board. One way is to provide the full story on hot-button topics and trends—such as headline-grabbing data breaches—and separating fear, uncertainty, and doubt from reality. Directors who are not technology experts may not realize that hackers aren’t always as clever as some news accounts make them seem. Laypeople often do not know that gaining unauthorized access to data doesn’t necessarily require advanced technical skills: hackers can simply prey on faulty processes and human behavior that is, well, human. Indeed, an effective method is phishing, a scam that uses deceptive e-mails to fool recipients into divulging confidential information, such as credentials for accessing IT systems.

By putting such events in context, CIOs can help board members identify—and evaluate—the true risks related to IT. Context can also help boards understand why certain IT investments should be made or prioritized, why particular technologies make sense for the company or a specific business model, and what steps boards themselves can take to fulfill their oversight role. (See “The Proactive Board.”)

THE PROACTIVE BOARD

Many boards have one or more technology veterans on their committees. The effectiveness of these directors can vary, however, depending on their level of engagement and the mandates of the committees. CIOs can help boards better evaluate a company’s IT, but boards can also help themselves. A good place to start is by taking one of the following two steps, which can be implemented in parallel with the strategies recommended for CIOs.

• Reserve a place on the audit committee for a technology expert. This board member could oversee efforts to test the integrity of the company’s IT systems, helping to identify and mitigate risk. An increasingly common—and effective—practice is the use of so-called ethical hacking: outside technology experts are hired to try to penetrate the security of the IT infrastructure, exposing areas for improvement. These efforts should be sponsored by the CIO but overseen by the audit committee.

• Create a technology committee. A dedicated committee can take the lead on assessing technology trends and strategic direction, as well as approving and overseeing major IT investments. But creating a technology committee isn’t the right move for every organization. If IT is not core to the business, then a company probably doesn’t need a technology committee. If IT is a critical component, however, then a company should be sure to include technology experts whose strengths and knowledge match the challenges and opportunities facing the organization.

Linking IT initiatives to the business problems they address is important, as is the ability to come up with roadmaps that show what technology will enable over the next few years. Such roadmaps help boards assess IT’s strategic direction.

Effective communication—using compelling, accessible language and images—is once again important. But so, too, is business acumen. A CIO needs to know the ins and outs of the company’s strategies and operations in order to develop these roadmaps. That’s why CIOs should be proactively engaged with other managers across the business, as well as with the board.

Hands-on demonstrations of technology can make a deeper impression on directors than a PowerPoint presentation ever could. Indeed, one CIO created an “immersion experience” so board members could touch and test some of the technologies the IT unit was planning to deploy. After this demonstration, the board approved a multibillion-dollar transformation of the company’s digital strategy.

Create an IT report for the board. CIOs have to instill confidence among board members that IT risk is under control and being proactively managed. Transparency is crucial: be forthcoming and thorough about the objectives, progress, and challenges of ongoing technology initiatives. Written expressly for the board and issued on a regular schedule, a “state of IT” report can be a powerful tool for keeping directors abreast of the status and payoff of projects. Constructing a report for board members, however, isn’t the same as writing one for management. While the C suite needs information that helps them make operational decisions, boards are more interested in information that helps them perform their oversight function and minimize risk.

When preparing a state-of-IT report, then, the objective is twofold. First, the report should provide insight into the progress and risks of major initiatives, the value they have generated, and IT’s impact on the bottom line. The IT department at Intel, for example, publishes an annual report—publicly available on the company’s website—that lays out the unit’s performance for the year. The report for 2014 noted that the IT department implemented advanced analytics software that generated more than $350 million in revenue[--“How Intel’s CIO Helped the Company Make $351 Million,” Wall Street Journal, February 18, 2015.--].

The second objective for the report is to convey this information in a concise and accessible way.

The CIO at a large global insurer took a savvy approach to preparing a report for the board—an approach that became the model for quarterly CIO updates. He created four simple dashboards, each of which was devoted to a category of IT metrics, such as financials (to demonstrate the value and costs associated with IT), technology risks (to show the status of patching server software and the status of testing and validating business continuity plans, among other things), customer satisfaction, and major IT projects. The dashboards were supported by a 15-page memo. While the dashboards gave board members a quick view of IT’s performance, the memo provided more detail, discussing important trends that had surfaced since the previous report, comparing the company with its competitors using industry benchmarks, and making projections for these metrics in the coming months or years.

In addition to a state-of-IT report, CIOs should prepare project briefs that facilitate board buy-in for technology adoptions or large undertakings. Three elements are critical: a clear description of the business problem, the trade-offs for various options, and the logic for the suggested path. In making the case for a planned upgrade of its IT architecture, one company created a 20-page brief for the board, outlining the pros and cons for all of the viable options. This helped the board understand that the recommended solution was the best option available and that the budget request was reasonable.

Proactively engaging with the board is entirely doable, and CIOs can begin today by using these three strategies. The only requirements are a willingness to make the first move and to put in the work that all close relationships require. Both parties will benefit. CIOs will spend less time defending IT and more time spurring it forward; boards will glean the insights they need and see the value IT creates.