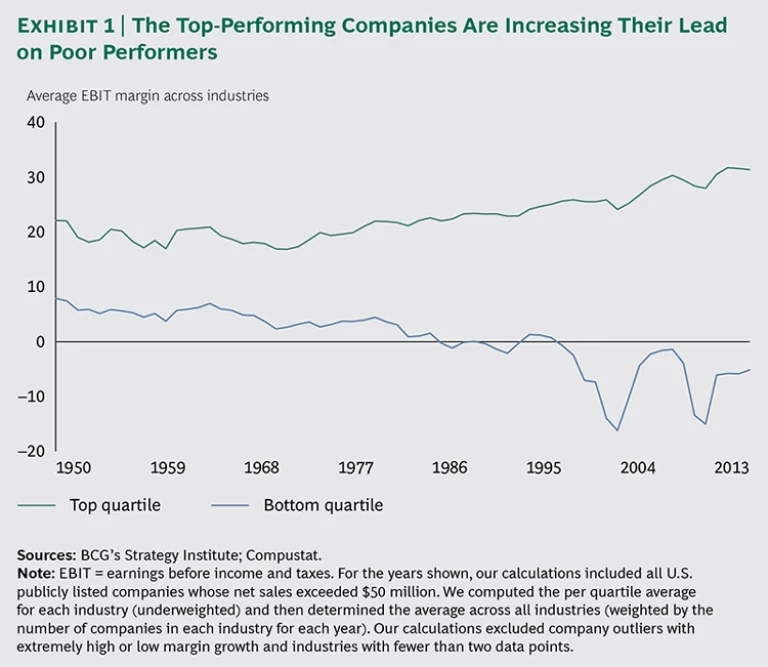

Leadership transitions increasingly happen when companies are at an inflection point, and as a result, new CEOs frequently face immediate pressure to make changes. The challenges are significant. Companies are being buffeted by rapidly evolving technology and digitization, increasing globalization, blurred industry boundaries, and regulatory shifts, among other factors. As the traditional sources of competitive advantage disappear, top-performing companies are increasing their lead on poor and average performers. (See Exhibit 1.)

To keep up with industry leaders—or to remain a leader—it is more important than ever for companies to undergo transformations. (See Transformation: The Imperative to Change , BCG report, November 2014.) We define a transformation as a profound change in a company’s strategy, business model, organization, culture, people, or processes. A transformation is not an incremental change but a fundamental reboot that enables a business to achieve a sustainable, quantum improvement in performance, altering the trajectory of its future. Because of the comprehensive nature of transformations and the need for companies to implement them quickly, transformations are complex endeavors, and the majority either fail to fully capture the potential value or exceed the time allotted to embed new behaviors and processes. Yet by adopting a clear methodology, companies can flip the odds in their favor.

Companies with stable management teams can also benefit from transformations, yet in our experience, a change in leadership offers a critical window of opportunity for implementation. Stakeholders expect changes to occur when a new CEO is hired. In fact, a principal risk for new CEOs is that they may resist taking action too quickly—or hesitate to make changes that go deep enough. The risk is especially high for insiders who are being promoted to the top spot or taking the reins alongside a strong chairperson. Yet through quick and decisive actions—even before taking the top job—new CEOs can seize the opportunity and put their company on the right trajectory for success.

The message for incoming leaders is clear: You need to take action immediately. By laying the groundwork in advance, you can be prepared to lead from the front with a clear vision, solid objectives, and the tools and processes to succeed.

The Boston Consulting Group has helped companies execute transformations that have led to significant financial impact. We have completed more than 500 transformations, generating a median annual impact of approximately $340 million through cost cuts, revenue increases, and the application of capital-efficiency levers; 150 transformations are currently under way. This body of work has helped us identify some clear principles and best practices that can help new CEOs—as well as board chairs and members of the C suite—successfully develop and implement a transformation effort.

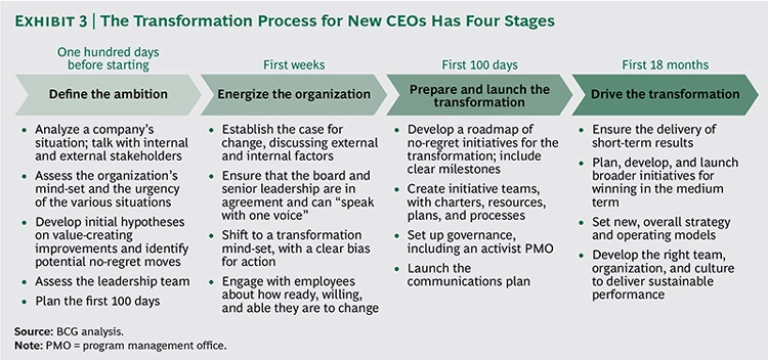

This report is a playbook for new CEOs. It lays out how and where to start and provides a transformation framework. The report then breaks the transformation process into four steps: the 100 days before officially starting, the first weeks on the job, the first 100 days, and the first 18 months. Because the framework applies to all transformations, while the four steps provide specific actions for new CEOs, there is some overlap. The report also includes case studies of successful transformations in various industries—retail, technology, and manufacturing, among others—to show what the process looks like in the real world.

The Transformation Framework

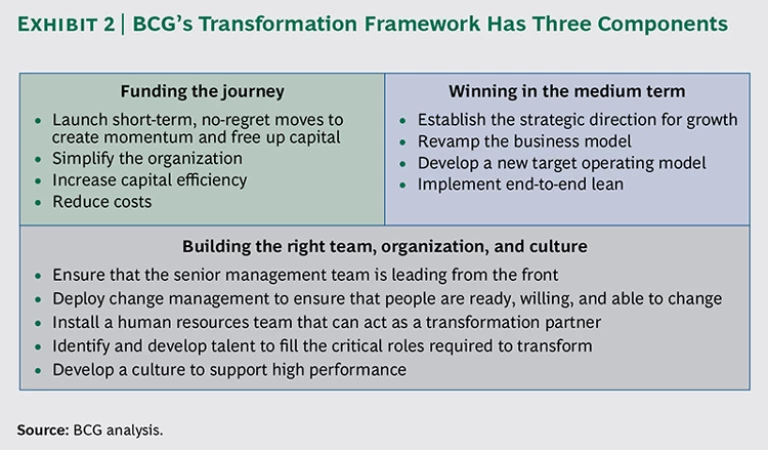

On the basis of our experience helping implement transformations across industries and regions worldwide, we have developed a proven framework that can help leaders define the collective transformation ambition for the company. (See Exhibit 2.) The framework has three critical components:

- Funding the Journey. Launch short-term, no-regret moves to establish momentum and to free up capital to fuel new growth engines.

- Winning in the Medium Term. Develop a business model and operating model to increase competitive advantage.

- Building the Right Team, Organization, and Culture. Set up the organization for sustainable high performance.

A transformation should include all three elements, but the relative importance of these components changes at various points in the process. In the beginning, funding the journey is often the most critical aspect, not only to establish momentum but also to free up capital rapidly. Over time, as a transformation takes root, the priorities typically shift toward winning in the medium term. Throughout a transformation, a focus on building the right team, organization, and culture is vital to ensuring that a transformation is not short-lived but rather becomes a long-term endeavor that delivers—and sustains—improved performance.

One Hundred Days Before Starting: Define the Ambition

New CEOs often have time—as much as 100 days—after unwinding themselves from most of the responsibilities of their former job and before they must assume those of the new position. This period offers a critical opportunity for leaders to take charge and define the organization’s collective transformation ambition. (See Exhibit 3.)

When defining this ambition, it is critically important for CEOs—whether hired from the inside or brought in from the outside—to adopt an investigative and analytical mind-set: “I need to learn more.” (For an example of an incoming leader who defined a bold transformation ambition, see “A New Retail CEO Hits the Ground Running.”) Incoming leaders should talk with as many critical stakeholders as possible, both inside and outside the organization, in order to educate themselves about the company:

- Employees, to determine if there is a consensus regarding the changes that are needed; ideally, leaders should speak with 30 to 50 employees from across all units and at all levels

- Customers, to get unvarnished opinions of the company’s performance in addressing their needs

- Industry and functional experts, to understand the company and the complexities or disruptions in the market

A NEW RETAIL CEO HITS THE GROUND RUNNING

A new CEO was hired to run a retail organization that had been losing market share for several years and that was starting to see profitability decline. During the 100 days before taking over, the CEO visited stores, talked with customers, studied international best practices to build on his own experience abroad, and talked with experts in the retail sector. Through that process, he realized that the immediate priority was to identify rapid, no-regret moves that could increase top-line sales and reenergize the organization.

While conducting this due diligence, the new CEO also developed a strong presentation to introduce his plan to the organization. As soon as he took over, he gave the presentation during the first executive-committee meeting, supporting the plan with the customer feedback he’d generated firsthand, along with his international experience with retail peers. In this presentation, he used very direct language and simple terminology, which made the messages powerful, credible, and resonant.

During his first month, the CEO gave similar presentations to larger groups of employees and managers, which provided clarity and reduced anxiety in the organization. He also traveled to meet the extended management team, visited crucial countries, and granted interviews to select media outlets—always with the same clear and consistent messages.

Within the first quarter, the company had begun to roll out several no-regret moves on the basis of his international retail experience and firsthand research, including a loyalty campaign, extended operating hours for a particular store format, and new promotions. The results jump-started top-line growth for the first time in years, leading to subsequent gains in market share. With those gains behind them, employees were more willing to accept the cost cuts and other measures required for the company to become leaner and more agile.

During these conversations, a new CEO should primarily listen, encourage open and honest discussion, and make sure that all possible dynamic factors and all possible solutions are being brought to the forefront. Through this process, the CEO must start to diagnose problems and create hypotheses regarding which aspects of the company require improvement. This means assessing the urgency of the various situations—in terms of both scope and timing—and determining whether the company should seek to transform a specific function, market, or division or instead undergo a more comprehensive effort that affects multiple areas of the company.

In both broad and narrow transformation efforts, new CEOs need to start identifying rapid, no-regret moves during this time—initiatives that are relatively easy to implement in the first 100 days and that can generate results in 3 to12 months. These no-regret initiatives should close performance gaps in a few critical areas, reduce costs, improve top- and bottom-line performance, and free up cash in order to fuel longer-term initiatives. (For an example of a leader who launched multiple measures to build momentum for a transformation, see “A Technology Leader Creates Momentum Through Rapid Moves.”) As new CEOs establish momentum with these initiatives, they should also clearly define the company’s goals for improving long-term performance—and how the company will sustain those improvements over time.

A TECHNOLOGY LEADER CREATES MOMENTUM THROUGH RAPID MOVES

At a global technology company, the head of a business unit realized that the organization was not winning the highly competitive war for talent. The company had dropped in the ratings at websites such as Glassdoor.com and in Fortune magazine’s annual “Best Companies to Work For” review. The results of employee engagement surveys had been falling for years. And the unit head knew from personal interactions with employees that they were not happy or motivated to go above and beyond. He wanted a transformation that would increase employee engagement, restore internal pride, and persuade employees to go the extra mile.

But his challenges did not stop there. Customer feedback was very troubling. For example, one customer commented: “When we look at your products, we can see how your organization is structured. Your products are siloed, with incompatible components and broken interfaces—which is just like your siloed organization. We need integrated solutions with components that work together to solve our problems, and we need them now.” Such feedback gave the unit head a second impetus for a transformation.

In response, he defined a bold ambition to transform the unit in order to win the war for talent, energize his engineers, deliver the integrated solutions that customers were demanding, and free up resources to deploy on opportunities for growth.

His first step was to conduct a thorough analysis of the root causes of the performance issues. On the basis of this analysis, the unit head defined the ambition for a step-change transformation across multiple dimensions, including growth, innovation, leadership capabilities, workforce quality, organizational efficiency, employee productivity, and culture.

Within the first few weeks, he selected the leadership team to drive the transformation program and communicated the case for change, initially among the top 150 leaders, and then across the business unit.

In the first 100 days, the unit head launched the full transformation program with multiple teams, a program management office, change-management processes, and an employee communications plan. Over the next year, the transformation delivered significant improvements across multiple performance dimensions—the result of a business unit leader conducting a thorough diagnostic and defining a bold transformation ambition.

The First Weeks: Energize the Organization

In the second step—the initial weeks of a new CEO’s tenure—communication becomes critical. Leadership transitions and transformations can be stressful periods for a company, and undergoing both simultaneously can make them doubly so. Yet success requires large numbers of people to go above and beyond to accelerate the pace of change. As a result, new CEOs must carve out the time to energize the organization and build momentum for the collective transformation ambition.

Specifically, new CEOs should start building a compelling case for change from their first day on the job. Initially, new CEOs should make the case to the board of directors and to the senior management team to achieve consensus so that they all “speak with one voice” regarding the transformation. Then, new CEOs should make the case to the entire organization. The case for change should acknowledge the company’s heritage and the hard work of employees, but it should also discuss external factors (such as the customer base, competitors, and capital markets), internal metrics (for example, operational and organizational performance and employee engagement), and the necessary measures the company will soon take in response. (For an example of a CEO taking dramatic steps to energize a company, see “A Consumer Packaged Goods CEO Revamps the Company’s Structure and Product Line.”) The case for change is typically made to internal stakeholders in various venues, such as workshops and town hall meetings, as well as through communication channels that allow the CEO to answer important questions on vision, approach, and tactical next steps.

A CONSUMER PACKAGED GOODS CEO REVAMPS THE COMPANY’S STRUCTURE AND PRODUCT LINE

A new CEO took over a global consumer packaged goods (CPG) company that had been languishing owing to declining sales and a sagging stock price. Recognizing that the company’s historic profit core was shrinking and that dramatic action was required, the CEO established a bold vision to change the shape and direction of the entire organization.

Specifically, the CEO split the company in two, creating a slower-growth domestic organization and a rapidly expanding international player. In addition, the least desirable divisions were sold off, which represented approximately 20 percent of the total portfolio. Finally, the CEO made several acquisitions, particularly in growth areas that could piggyback on the company’s existing distribution channels.

Executing this transformation required strong leadership, not only from the CEO but also from the entire senior-management team. Senior leaders were assigned to new organizations on the basis of their skills and experience in various markets. In addition, the new CEO changed the board to include members with a more activist investor mind-set who would help shape the company’s growth agenda.

Collectively, these measures more than doubled the company’s market value and moved its total shareholder return into the top quartile of the CPG sector.

In addition, leaders should tailor the message and the communication style to the company’s situation. Some companies have well-established ideas about their overall direction and sense of purpose; these companies can focus primarily on short-term performance and delay setting a more visionary agenda. Other companies are tired of short-term thinking and constant cuts and need a more compelling story about where the new CEO intends to lead the company. In all cases, it is critical for the CEO to speak with authenticity and a sense of urgency. (For a case study of a company that had to take rapid and dramatic steps during a transformation, see “A Pharmaceutical Company Transforms Itself and Generates $20 Billion in Value.”)

A PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY TRANSFORMS ITSELF AND GENERATES $20 BILLION IN VALUE

A global pharmaceutical company had been extremely successful—consistently growing earnings by 15 percent a year and reinvesting all remaining excess capital. However, management challenged itself to improve performance through a comprehensive transformation of the company. The investor community also indicated that the company could create more value by accelerating earnings growth. As the company began to consider a transformation, it faced an additional challenge—a hostile take-over attempt.

In response, the company launched an extremely rapid initiative to cut activities that generated a low return on investment and restructured to quickly increase earnings. The project team analyzed and redesigned the entire company in only three months and then implemented the new design. Despite the rapid launch, virtually all functions and business units were included in the scope. Notably, the company implemented the transformation through both senior leaders and managers who were several levels down in the organization hierarchy. This approach led to very specific, pragmatic solutions, and it built momentum for the initiative throughout the company’s workforce.

Through this transformation, the company cut its annual costs by more than $500 million and increased its earnings growth rate from 15 percent to more than 20 percent. These changes yielded an improvement in company value of approximately $20 billion. The transformation also represented a value-creating alternative to the hostile takeover and enabled management to strike a deal with a different acquirer on more favorable terms.

The First 100 Days: Prepare and Launch the Transformation

The first 100 days of the process are critical in that they set the trajectory for the overall transformation—and indeed for the CEO’s tenure. Leaders must put the foundation in place during this time, balancing a long-term vision with day-to-day reality. As the transformation starts to take shape and the case for change becomes clear, the CEO must shift gears from planning the transformation to actually leading it. This means immediately kicking off the rapid, no-regret moves that will deliver impact within 3 to 12 months, creating and enabling initiative teams, setting up the overall governance and change-management program for the transformation, and launching the communications plan.

These no-regret initiatives build momentum for the larger effort, win over internal skeptics who may doubt that change is actually happening, generate credibility for the new leadership team, and often free up capital that can be used to fund subsequent measures. As a result, these initiatives further help energize the organization.

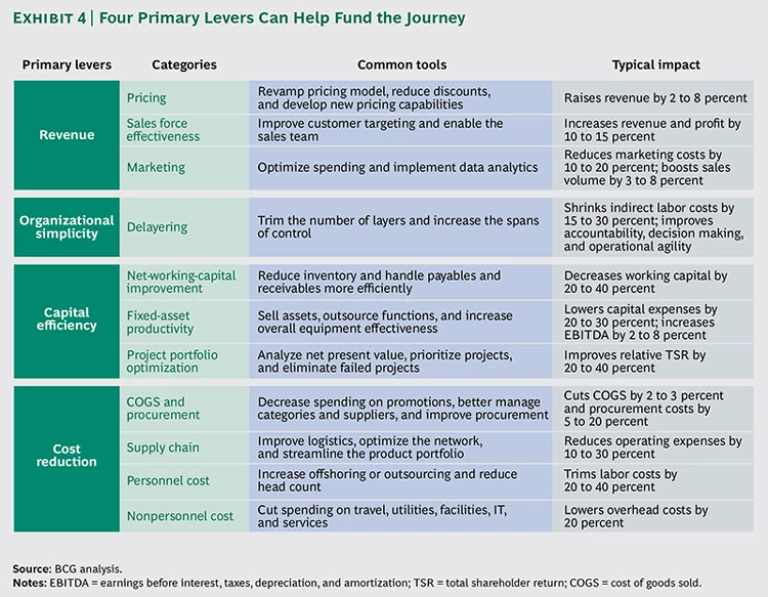

The four primary levers for funding the journey are revenue, organizational simplicity (delayering), capital efficiency, and cost reduction. (See Exhibit 4.) In choosing where to start, many companies understandably opt for the two obvious solutions: cost cutting and organizational simplicity. This approach works, but revenue and capital efficiency can often generate a significant impact as well. (For a case study of a company that launched strong early stage initiatives, see “A Manufacturer Lays the Groundwork for an Ambitious Transformation.”)

A MANUFACTURER LAYS THE GROUNDWORK FOR AN AMBITIOUS TRANSFORMATION

The U.S. housing industry suffered a steep correction following the 2008 global financial crisis. The CEO of a manufacturing company responded with a number of measures that did not improve its financial performance.

Realizing that stronger measures were called for, the CEO decided to launch a more ambitious transformation program, with the goal of increasing earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) in one year, independent of market growth or price changes.

To prepare for the transformation, seven teams—four composed of employees from business units and three made up of employees from major function areas—developed a roadmap of initiatives around growth, pricing, cost reductions, and operational productivity improvements. Each initiative specified the target EBIT improvement, required actions, milestones, and resources. The company also enabled the teams to meet these aggressive goals by providing them with new analytical frameworks and problem-solving methodologies and tools.

To ensure the overall program delivered on the EBIT ambition, the company set up a steering committee composed of senior executives and a program management office (PMO) to provide governance and drive the pace of the transformation.

The PMO provided rigorous program management, including the monthly tracking of improvements. The reports highlighted any initiatives that were exceeding or falling short of their targets. This gave management a clear view of overall performance and flagged situations that required interventions.

As a result, the company was able to deliver on the ambitious EBIT target set by the CEO. In addition, the business units adopted a continuous- improvement approach to capture gains after the formal transformation program ended.

Once measures are under way, there is a real risk of prematurely declaring victory and moving on to other priorities, which all but assures that the transformation effort will fail. Instead, it is critical to maintain focus and ensure that initiative teams are on track to achieve results. Assuming that some form of project tracking has been put in place, now is the time to ensure that leaders have full transparency into the progress of each initiative. Regular review sessions, facilitated by the program management office (PMO), should provide sufficient information for leaders to know whether—and how—they need to intervene.

In particular, CEOs should avoid a number of common pitfalls during this phase, including the following:

- Insufficient accountability among the owners and sponsors of the initiatives

- Failure to have in place clear plans and roadmaps, backed with specific actions and milestones that are linked to financial objectives

- A lack of resources and expertise on initiative teams

- Management incentives that do not support the objectives of the transformation

- Failure to engage stakeholders and overcome institutional resistance

The First 18 Months: Drive the Transformation

As the broader transformation begins to gain momentum and initial fund-the-journey efforts begin to take hold, CEOs must launch broader initiatives to win in the medium term, set the new strategy and operating model, and build sustainable performance.

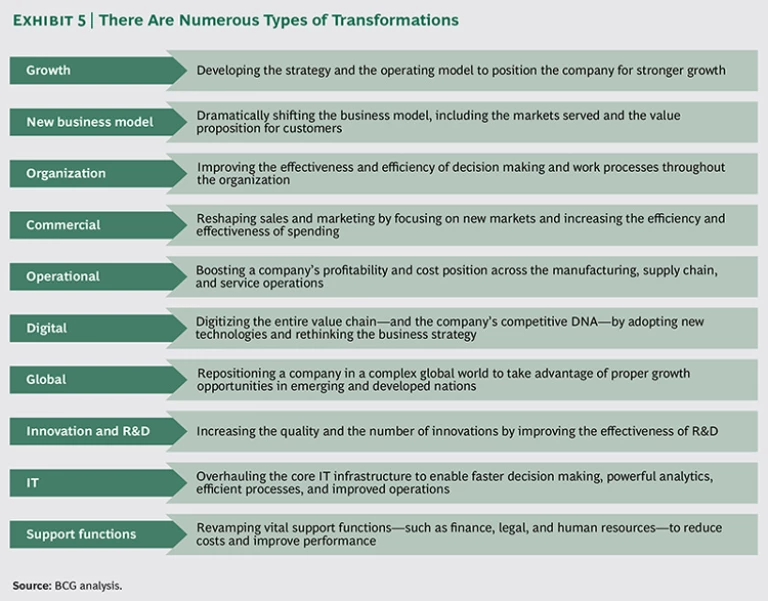

Winning in the Medium Term. This phase requires delivering on transformation objectives that go beyond the short-term goals of earlier, fund-the-journey efforts. The specific objectives will vary by company, but common to all transformations is the need to establish a fundamentally different competitive position, leading to a medium-term step-change in performance. Winning in the medium term could entail a wide range of initiatives to transform, including driving growth, launching a new business model, revamping commercial processes or operations, building digital capabilities and ventures, and transforming internal support functions, such as R&D, IT, or human resources (HR), among others. (See Exhibit 5.)

Compared with funding-the-journey measures, initiatives to win in the medium term are usually more difficult to conceptualize, as they require breakthrough thinking, usually in areas that are less familiar for the organization. These initiatives are also harder to staff and implement, and they call for managing interdependencies across functions and business units. (For an example of a CEO-led transformation that delivered sustainable gains, see “A Global Insurer Implements a Value-Based Transformation.”)

A GLOBAL INSURER IMPLEMENTS A VALUE-BASED TRANSFORMATION

A new CEO took over at a global insurance company that had multiple lines of business. The CEO conducted an outside-in analysis to assess the company’s current situation, along with its capabilities, its competitive position both globally and in individual markets, and industry analysts’ perceptions.

This process identified some clear challenges. The company’s return on capital was low, and its capital position was weak. The company also lacked a rigorous process for allocating capital and had inefficient cost structures and an unfocused portfolio of business units, whose performance varied widely.

Through this analysis, the CEO defined the ambition for a transformation and established explicit financial targets. Once he took over the top job, he built momentum for the effort in a series of meetings with the board of directors and the executive committee.

As part of the transformation, the CEO looked at specific insurance segments and restructured the company into 40 “cells.” Each cell represented businesses and markets with similar underlying characteristics (for example, vehicle insurance in the UK, pension insurance in Poland, and corporate insurance for large companies in the U.S.). The CEO then assessed the performance of the individual cells across several dimensions through financial analyses and the evaluation of market prospects.

On the basis of the results, the company grouped its businesses into three clusters: “grow” (the top 25 percent), “turnaround” (the middle 50 percent), and “divest” (the bottom 25 percent).

Within the first 100 days, and backed by the senior management team, the CEO had begun communicating a new 18-month initiative to the entire organization.

The transformation would include specific corrective actions to improve the cash flow performance of the turnaround units. In addition, the program would reduce costs throughout the company and strengthen the capital management process, with more integrated planning and a better performance-management cycle.

In all, the effort generated more than $400 million in savings in its first year—a savings that included a reduction of 25 percent in the head count of senior management.

That success stemmed from several factors. First, the company took a strictly fact-based approach to analyzing business performance, in part by eliciting an outside-in assessment from the investor and analyst communities. Second, the CEO ensured that all executive committee members had accountability for specific initiatives. And third, the implementation plan was clear from the start, thanks to strong communication and full buy-in from the management team.

Setting the New Strategy and Operating Model. While driving short-term and medium-term initiatives, companies benefit from stepping back and looking at their overall strategy and operating model. This does not need to be a broad strategy- planning exercise. In fact, we find that a targeted workshop-based approach with the senior leadership team—and the appropriate data and analysis—can lead to a strong outcome and do so in a highly efficient manner that doesn’t distract the leadership team from driving the overall transformation. This approach ensures that there is buy-in from the top team and that the strategy leads to immediate operational adjustments. (For an example of a company that implemented strategic changes as part of its transformation, see “A Bank’s Transformation Boosts Customer Satisfaction and Financial Performance.”)

A BANK’S TRANSFORMATION BOOSTS CUSTOMER SATISFACTION AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE

In the wake of the financial crisis, a large bank was struggling to resume a growth trajectory. It suffered from poor profitability and process inefficiency, compared with its peers. The bank also had severe liquidity issues and high write-downs on loans in both core and distant markets. More fundamentally, it had an unclear value proposition for customers and little organizational focus on performance and collaboration among employees.

In response, the CEO and leadership team launched a three-step transformation aimed at improving customer satisfaction and financial results.

The first step was to reorganize the company around the customer experience rather than around divisions and functions, which was the current, silo-based approach. That process clarified the roles for specific functions, and it rewired processes to foster greater collaboration across departments. At the same time, the company revamped its leadership team, making some new hires and giving some current leaders new roles.

The second step was developing a new strategy—new business leaders were tasked with defining the strategy for their units. Those individual strategies were grouped into one major transformation effort that was owned by the CEO and had three specific objectives: better customer satisfaction, greater efficiency, and a performance-based culture.

In the third step—currently under way—the CEO and leadership team are putting their full focus on executing the new strategy.

Building Sustainable Performance. Many organizations that deliver results during the transformation have a tough time sustaining their hard-won performance improvements. The goal of every CEO should be to achieve success during the first 18 months of the transformation program and then maintain it well beyond that point. This is what separates the most transformative CEOs from the rest of the pack. It is imperative for a CEO to own this phase and closely involve the chief human-resources officer and other influential leaders across the company.

There are five important aspects to developing the right people and organization required to support a successful, sustainable transformation:

- Ensure the commitment and change capabilities of the executive team, including their ability to set the right priorities, mobilize and energize initiative teams, and hold themselves accountable for the results.

- Deploy change-management tools and processes (such as an activist PMO, roadmaps, and rigor testing) to engage stakeholders and deliver results. (For more on rigor testing, see “ The Hard Side of Change Management ,” Harvard Business Review, October 2005.)

- Install an HR team that can act as a transformation partner, anticipating talent and leadership needs, rather than as a mere service provider.

- Build a talent pipeline that can help fill crucial roles, and develop capabilities in areas critical for the transformation, such as go-to-market strategies, pricing, sourcing, lean methods, digitization, innovation, and HR.

- Simplify the organization and culture to sustain high performance in conjunction with the new strategy. Usually this entails eliminating waste and low-value work, trimming bureaucracy, implementing shared services, automating processes, and enabling the organization to continue taking these steps on an ongoing basis.

For most new CEOs, the imperative to change is a given; how CEOs respond to this imperative is not. Those who stand out from the pack quickly define a bold transformation ambition—ideally before taking the reins—and then move forward to energize the organization, prepare the program, and drive the transformation. Through quick and decisive actions—while time, the board, and investors are still on their side—new CEOs can seize the opportunity to lead a transformation and put their company on the right trajectory for success.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maya Gavrilova, Jonas Lumby Jensen, Paul Millerd, Louise Herrup Nielsen, Mai-Britt Poulsen, and Fredrik Vogel for their contributions to this report. The authors also are grateful to Jeff Garigliano for his assistance in writing this report and Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, Trudy Neuhaus, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to the editing, design, and production.