Drawing on analysis from proprietary tools, BCG assesses challenges facing container shippers, including overcapacity and low returns, and offers recommendations for restoring carriers’ profitability.

The tone of The Boston Consulting Group’s 2012 report on the container-shipping industry (which assessed industry realities in 2011) was somber. (Charting a New Course: Restoring Profitability to Container Shipping, BCG report, October 2012.) We noted that multiple challenges were plaguing companies, particularly container liners, or carriers. The challenges included record losses, depleted cash reserves, the specter of bankruptcy, and slowing demand for carriers’ services. Equally sobering, competitive pressure in the liner industry was intensifying, along with price wars triggered by carriers’ reactions to a self-inflicted supply-demand imbalance.

Our analysis of the industry in 2013 and 2014 reveals that the picture has not changed much since 2011. Following the volatile period from 2009 through 2011, observers were hoping that the industry would bounce back somewhat, buoyed by economic recovery from the most recent global recession. But the eagerly anticipated uplift has not yet materialized. Indeed, companies still grapple with numerous challenges that are being driven primarily by overcapacity and a highly fragmented industry structure.

Choppy seas indeed, requiring navigational savvy—but not necessarily cause for abject despair. In fact, some carriers have managed to turn a profit in this tough environment, suggesting that there is hope for the industry.

Recovery will take strenuous work, but we believe that even the more embattled carriers can catch up to their profitable peers. To do so, they’ll have to come to grips with the industry’s new normal, establish a solid strategic position, revisit their business and operating models, pursue new transformation levers, and rethink alliance models.

In this report, we address the situation in several ways:

- Analyzing the industry’s persistent supply-demand gap and forecasting the five-year outlook for freight and time charter (TC) rates

- Examining the industry’s fragmented value chain and financial performance

- Considering more sophisticated alliances that could help carriers create more value

Continued Overcapacity with No Market Recovery

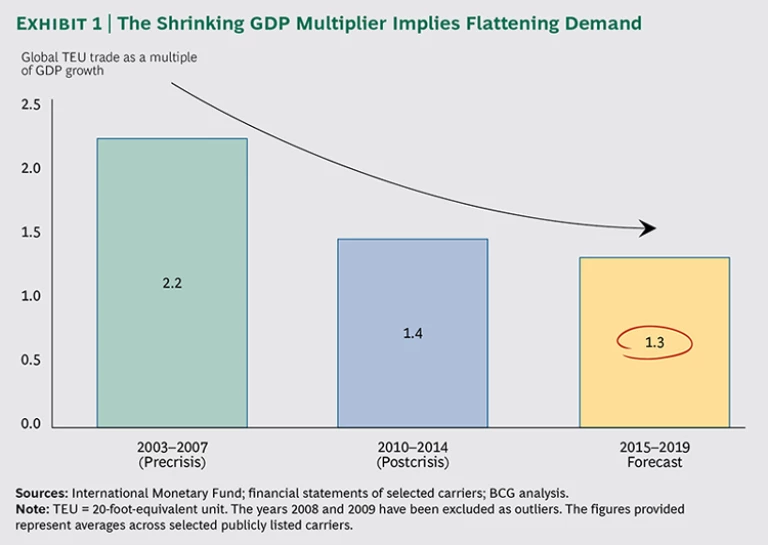

The container-shipping industry has changed, with significantly lower demand growth becoming the new normal. The GDP multiplier, which the industry often uses to express global 20-foot-equivalent-unit (TEU) growth in relation to global GDP growth, is shrinking. (See Exhibit 1.) Over the next five years, we expect to see an overall GDP multiplier of just 1.3—considerably lower than the pre-crisis values of 2.2 or more in even earlier years.

Two critical forces are driving the decline in the multiplier:

- Less Offshoring of New-Production. The global shift of manufacturing from Western economies to lower-cost countries is a onetime effect that is losing steam. Once production has been offshored, it does not add to incremental trade growth. Indeed, a series of BCG studies reveal future downside risk through increased “reshoring.” U.S. and other Western companies have been moving their manufacturing back home as the manufacturing cost advantage erodes. Some industries, such as furniture and appliances, may be approaching a tipping point at which moving production closer to customers becomes more attractive—and reduces the demand for sea transportation.

- Plateauing in the Levels of Containerization. BCG analysis indicates that today, most commodities suitable for containerized transportation have already been migrated to containers, stabilizing the overall containerization levels at about three-quarters of global general cargo. Significant additional containerization jumps are not likely in the years to come.

We also see unfavorable trade-growth dynamics affecting global demand for container-shipping capacity. For instance, we expect more incremental TEU demand growth to come from the back-haul trade routes, or trades (for example, from the U.S. to China), for which capacity is readily available but underutilized. Moreover, some fast-growing regional trades (for example, in Asia) have much shorter round-trip times and, hence, require less additional vessel capacity than the longer-distance deep-sea trades. Therefore, projected overall TEU-throughput growth is the wrong variable to plan with. Instead, carriers need to focus on incremental TEU capacity demand per trade.

For container shipping, this means lower TEU-capacity-demand growth rates than in past years. Carriers must anticipate this new normal in their business and fleet-capacity planning.

Understanding Expanding Capacity Supply

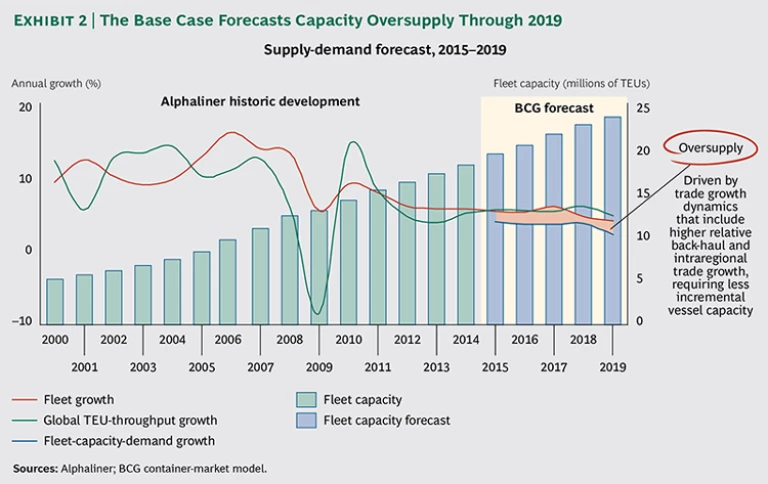

The sluggish demand outlook has not discouraged carriers from ordering new tonnage. BCG expects the global fleet to increase by 30 percent over the next five years—from 18.5 million TEUs today to 24 million TEUs in 2019. Of this new tonnage, we expect roughly 3 million TEUs, equal to roughly 50 percent of the expected deliveries, to stem from ultralarge container vessels with capacities exceeding 13,000 TEUs.

Despite the challenging market circumstances, many carriers, pursuing lower slot costs and higher competitiveness, continue to order new and larger vessels. Recently, several carriers were engaged in discussions to place orders for new 18,000- to 20,000-TEU giants. However, falling bunker prices toward the end of 2014 and in early 2015, as well as less flexible deployment options, make this investment less appealing. The reason: the slot-cost scale advantage of the largest vessels

of 18,000 to 20,000 TEUs over smaller vessels of 10,000 TEUs decreases from about 20 percent to less than 15 percent. This calculation assumes stable utilization levels, but in practical terms, many alliances might find it difficult to fill such capacities on a weekly basis.

To explore how demand and supply changes might play out, we built a comprehensive market model to forecast scenarios over the coming years. We took into account factors such as demand growth rates per subtrade, an outlook on future vessel supply, different speed scenarios, and implied cascading effects of an influx of larger vessels.

The Persistent Supply-Demand Gap

Our market model forecasts excess supply of container-shipping fleet capacity through 2019 unless new-vessel ordering decreases significantly—a development that we don’t expect. The following three scenarios emphasize different dynamics:

- Base Case. The most likely scenario, the base case implies steady supply growth.

- Optimistic Case. An optimistic outlook would mean significantly less vessel ordering.

- Pessimistic Case. The potential impact of moving away from slow steaming due to declining bunker prices is gloomy.

The Base Case. The shrinking GDP multiplier and flattening demand for containerization, together with the substantial increase in the global fleet, will contribute to continued oversupply through 2019. The base case, which we consider the most likely scenario, predicts annual supply growth that results in a vessel supply that will be 0.9 to 2.5 percent higher than capacity demand growth over the next five years. (See Exhibit 2.) This is in addition to the existing oversupply in the market.

The Optimistic and Pessimistic Cases. The optimistic case considers a sharp 50 percent reduction in vessel orders through 2019 beyond current order books, which could close the supply-demand gap and even turn it slightly positive in 2019. But for this to happen, carriers would have to order about 300 fewer vessels than expected in the base case through 2019: 70 of the 300 could be ultralarge vessels ranging from 13,000 to 20,000 TEUs. As of January 2015, the fleet numbered about 190 ultralarge vessels and the current order book included about 110 vessels in the same size segment.

The pessimistic case assumes decreasing bunker-fuel prices, which were nearly halved at the end of 2014. In this scenario, price decreases might act as an incentive to encourage companies to start increasing vessel speed again. This, in turn, would release additional capacity into the market and further widen the supply-demand gap. In this case, we assume an increase of one knot in 2015 and an additional knot in 2016 on all deep-sea trades. Furthermore, our model also incorporated a 50 percent reduction in projected new orders as a response to the released capacity. This scenario would increase overcapacity by 2 to 3 percentage points over the base case from 2016 through 2019.

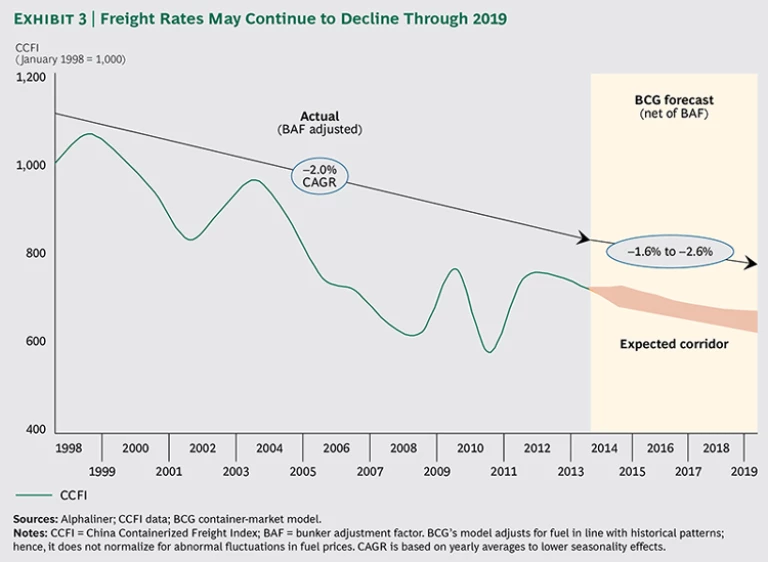

The Consequences of Overcapacity. Owing to persistent overcapacity, freight rates will remain under pressure as carriers strive to fill vessels. However, many factors in addition to the supply-demand gap influence freight rates, making forecasts less reliable. Examples include carriers’ failure to stick to published general-rate increases and less transparent surcharges factored into all-in rates, such as the bunker adjustment factor (BAF), congestion, and security surcharges.

Overall, assuming stable fuel prices, we expect freight rates to decline by 1.6 to 2.6 percent annually until 2019. (See Exhibit 3.) These numbers are in line with the 2 percent annual decline in freight rates (adjusted for BAF surcharges) that the industry has experienced since 1998.

BCG uses the following two approaches to triangulate potential freight-rate developments:

- Cost-Out Model. Given the weak market fundamentals and fragmentation in the industry, to fill their ships, carriers will likely stick with a price floor at the level of marginal costs. Consequently, their cost savings will be passed on to customers in the form of lower rates. Therefore, many shipping stakeholders recognize the ability to take out costs as a strong proxy for estimating future freight rates. The cost-out model is inspired by BCG’s experience-curve concept, which shows that unit costs decline as cumulative volume increases over time. This model thus predicts cost reductions by carriers if they can improve along the experience curve (by, for example, rationalizing operational processes, enhancing efficiency, and improving scale). The prediction is based on the historical relationship between unit slot costs and accumulated industry capacity. We have further verified this model by forecasting average vessel size and associated lower slot cost. The approach results in a unit-slot-cost reduction of 1.6 to 2.6 percent annually.

- Utilization Model. This model builds on expected utilization changes and forecasts freight rates on the basis of the historical relationship between the two factors. The model suggests a decline of 1.8 percent annually going into 2019.

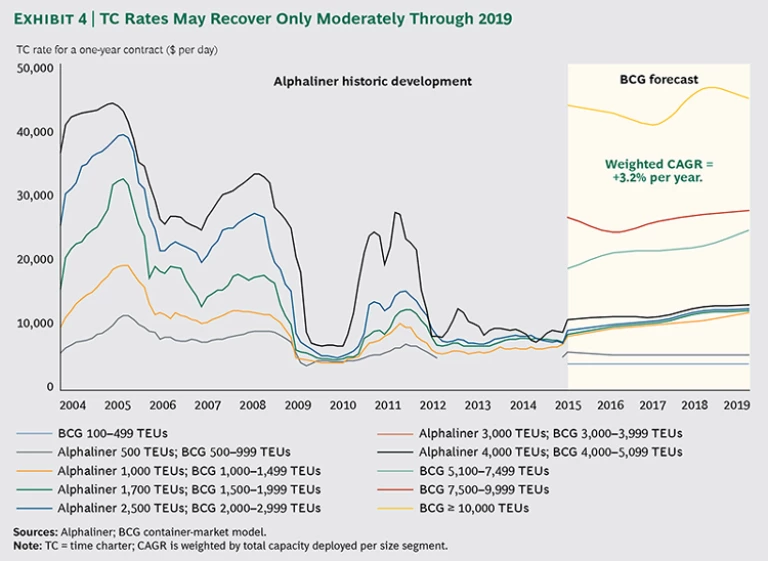

In addition to watching freight rates, many in the market—ship owners with revenues in mind; carriers with their cost base in mind—closely watch TC rates, the daily rates for chartering a vessel. TC rates are also affected by the continued supply-demand imbalance, making a recovery to past levels unlikely. Weighted across all vessel segments, these rates are projected to increase by 3.2 percent per year through 2019 on an aggregate level, but individual changes will vary depending on vessel size segments. (See Exhibit 4.)

In contrast to freight rates, the slightly positive development in TC rates can, for the most part, be explained by the increases in operating expenses (opex)—costs related to crew, maintenance, and consumables on board. Carriers are, however, likely to experience declining TC costs in the coming years as longer-term contracts signed during the peak periods (for example, from 2004 through 2008 and from 2011 through 2012) are renewed at substantially lower rate levels.

Our model forecasts TC rates for the various vessel-size classes, but the overall trend is being driven upward by the small and midsize classes of 1,000 to 5,100 TEUs. For these classes, we expect TC rates to achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7 to 10 percent between now and 2019. Larger Panamax-class ships (4,000 to 5,100 TEUs) will face emerging challenges resulting from the Panama Canal expansion project, which, by 2016, could more than double the canal’s capacity for service vessels with up to 12,000 to 13,000 TEUs. However, we believe that these vessels could find alternative deployment as large feeders or as vessels serving intraregional and emerging markets.

Still, the significant influx of heavy tonnage on the east-west trading routes will probably put some pressure on midsize and even large vessels’ TC rates. Today, these rates are at somewhat healthy levels, but they could experience negative CAGRs—such as –1.4 percent and –1.0 percent for vessel size classes of 7,500 to 9,999 TEUs and 10,000 or more TEUs, respectively.

Accelerating Internal Change

To lift their profitability, global carriers will need to adopt a two-step approach.

This approach could provide a light at the end of the tunnel for many carriers. However, to achieve such gains, carriers will have to stretch themselves to reach far beyond their current practices. Here, we examine a three-part framework that could help them accelerate their internal transformation. In the next chapter, "Extracting More Value from Alliances," we focus on how carriers can achieve greater synergies and scale from their alliances.

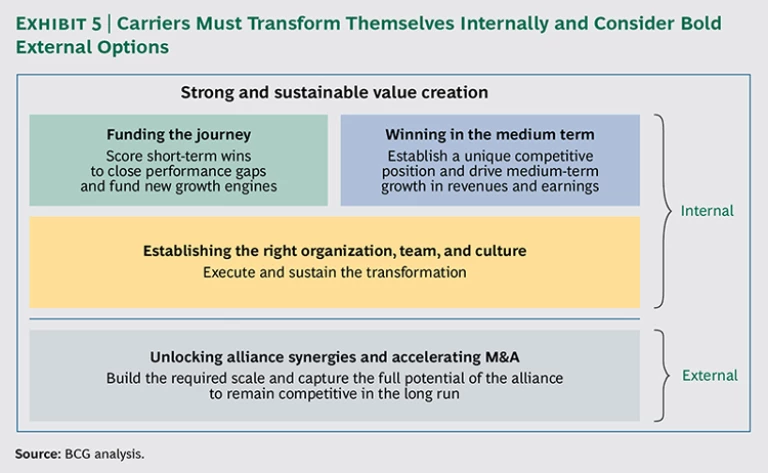

BCG's transformation framework comprises three interconnected parts aimed at delivering strong, sustainable value creation: funding the journey, winning in the medium term, and establishing the right organization, team, and culture. (See Exhibit 5.) In each part, carriers can extract greater value from commonly deployed change levers as well as explore “next frontier” levers.

Funding the Journey

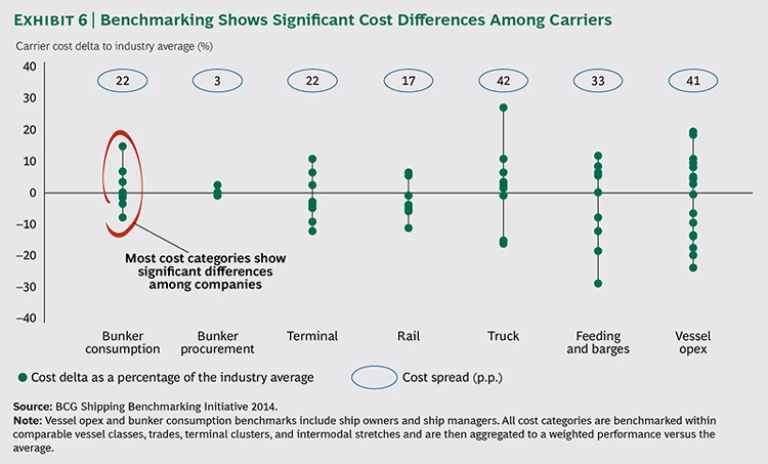

To fund the journey, companies launch initiatives aimed at scoring immediate wins that generate measurable bottom-line impact. In the shipping industry, most carriers have launched cost-efficiency initiatives to fund their transformation journeys. However, BCG’s Shipping Benchmarking Initiative (SBI) shows significant variances among carriers across major cost categories. (See Exhibit 6.) There is a 22- to 42-percentage-point spread in cost-delta-to-industry-average performance between best and worst peers in most categories.

CHANNELING MANAGERIAL ATTENTION AND RESOURCES TO WHERE THE DOLLARS ARE

Because many carriers lack a clear view of their cost performance, their management has difficulty prioritizing resources. As a result, they launch too many initiatives in too many areas of the organization, trying to “boil the ocean.” They need instead to focus on cost reduction programs that offer the largest savings potential. Full internal cost transparency (including accurate profit-and-loss statements at the container box level and continual benchmarking against the market and best-in-class peers) can help.

BCG’s Shipping Benchmarking Initiative (SBI) has helped numerous carriers achieve that transparency across critical cost categories, such as bunker, terminal handling, intermodal, and ship management. More than 50 leading shipping companies with more than 2,500 vessels participate in the SBI, including ten large carriers.

The results, in which companies remain anonymous, are available only to participants and their operations teams and help carriers optimize their transformation programs in the following ways:

- Facilitating constructive, fact-based team dialogue

- Identifying root causes behind variations in performance

- Monitoring performance against competitors and peer groups

- Identifying new best practices and optimizing initiatives

- Quantifying expected bottom-line impact to improve target setting and resource allocation

Leading participants consider the SBI the most comprehensive and actionable benchmark in the shipping industry. The SBI is open to companies across all major shipping segments, including container, tanker, and dry-bulk shippers.

Often, the variance stems not from differences in scale but from variations in procurement and operational practices. Benchmarking enables shipping companies to realize the full cost-reduction potential and focus managerial attention. (See “Channeling Managerial Attention and Resources to Where the Dollars Are," below.)

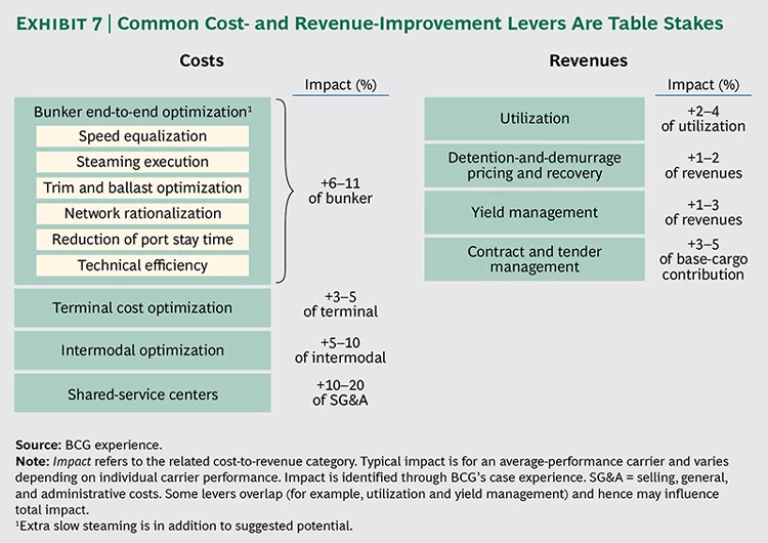

In large part, the shipping industry’s few leading companies have outperformed their peers thanks to their scale and uncompromising focus on cost reduction. However, owing to the relentless pressure created by weak fundamentals in the industry, most carriers have limited their transformation efforts to cost or top-line improvements gained by addressing common improvement levers. (See Exhibit 7.)

For instance, most have stepped up their programs aimed at reducing bunker consumption by equalizing sailing speed, optimizing steaming execution, reducing port stay time, and pursuing new trimming approaches. These moves can yield bunker consumption savings of 6 to 11 percent, savings from speed reductions, and additional benefits through vessel retrofits and technical modifications requiring some capital expenditure. Many carriers have also renegotiated terminal contracts and adopted more advanced procurement strategies in intermodal and depot categories. And some have offshored certain activities—such as documentation, accounting, and customer service—to shared-service centers in lower-cost countries.

On the commercial side, many carriers have launched initiatives aimed at improving vessel utilization and yield management, and they have implemented more effective methods for recovering surcharges such as for detention and demurrage. The results of such efforts vary depending on each carrier’s starting point, but some companies have lifted their operating margins by as much as 3 to5 percent by pulling these levers.

Because most companies have begun applying these improvement levers, the resulting gains have become industry table stakes, delivering advantage only until competitors catch up. Still, we believe that these levers contain significantly more value potential. Capturing that value can help carriers further fund their transformation journey.

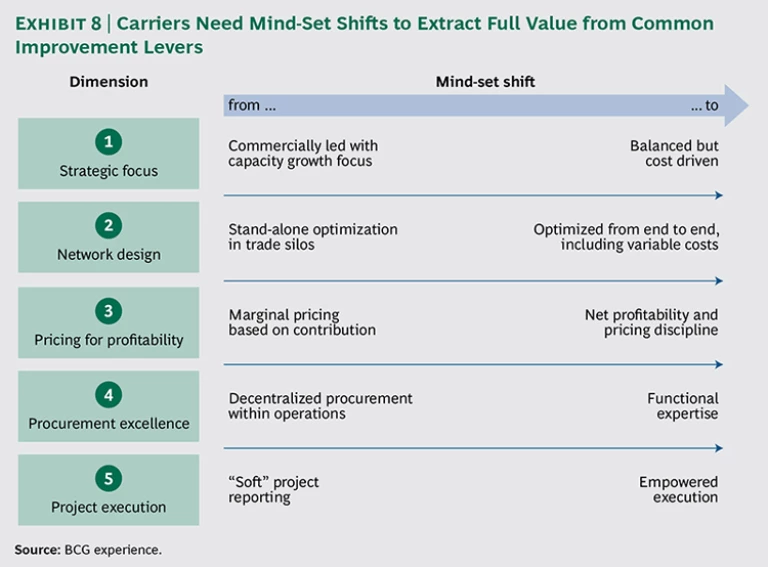

To tap into that remaining potential, carriers must make a mind-set shift across five dimensions: strategic focus, network design, pricing for profitability, procurement excellence, and project execution. (See Exhibit 8.)

Strategic Focus. Carriers must shift from commercially driven decision making to more balanced decision making with strong emphasis on cost efficiency. When a carrier is designing its global network, operational and procurement functions need more leverage.

Network Design. Many carriers take a piecemeal approach to managing their network, organizing themselves into trade silos that give business unit leaders the incentive to optimize their own parts of the network—perhaps at the expense of overall network performance. Admittedly, carriers in an alliance might have limited control over network decisions, but even they should strive to break down trade silos to capture the full benefit of optimizing and consolidating gateway terminals and transshipment hubs in their network. This approach allows for cost reductions through more efficient voyages at lower and equalized speeds, as well as more competitive terminal and intermodal costs. The savings, in many cases, go straight to the bottom line.

Pricing for Profitability. It is common for carriers to focus on marginal pricing to beef up vessel utilization and to cover their high fixed costs. Because carriers lack transparency into net profitability at the container box level, many unwittingly accept unprofitable cargo when considering all variable and fixed costs associated with a shipment. As a result, potential efficiency gains and cost savings get passed on to customers in the form of rate reductions. Instead, carriers must achieve cost transparency at the box level and enforce a stricter pricing discipline—even if this means losing cargo on routes that are not cost competitive.

Procurement Excellence. Carriers must develop strong functional-procurement expertise. Historically, procurement in critical cost categories has been scattered across independent operational departments and regional organizations that have rich industry knowledge but little procurement expertise. In certain large cost categories—such as intermodal—procurement processes are still led by local offices. Consequently, carriers can miss out on opportunities to secure favorable supplier terms by, for example, bundling vendors across locations, leveraging electronic sourcing platforms, and implementing advanced negotiation tactics. Setting up a global procurement function can help carriers implement advanced category strategies and achieve new levels of cost efficiency. The results are lower charges for third-party suppliers such as terminal or intermodal operators, equipment manufacturers, and container depots.

Project Execution. Many companies formulate ambitious improvement programs but fail to execute them effectively because of problems related to, for example, “soft” project reporting and confusion over who will drive which change activities. To surmount this challenge, carriers must infuse discipline into project execution. Case experience shows that the most successful programs establish an “activist” transformation management office (TMO) to centrally drive the execution of change programs across regions and functional departments. Moreover, senior leadership assumes full accountability for the results of these programs, with each leader committing to clearly defined individual targets. In such companies, change becomes the language of business through a TMO armed with a robust suite of tools critical to risk management, communications, capability development, and project status monitoring. The TMO is vital for sustaining the “burning platform” required to execute fund-the-journey initiatives.

Winning in the Medium Term

Having funded the transformation journey by securing short-term wins, carriers must use the resulting momentum to generate medium-term competitive advantage. This requires rethinking their business model and backing it with the right operating model.

Rethinking the Business Model. As noted earlier, many carriers are not large enough to play the global-scale game, and they lack a strong position as niche specialists. To break out of this middle position, many of these carriers have entered alliances to boost scale, but the majority remain unprofitable. They therefore need to rethink their business model, clarifying how they plan to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. The business model signifies where a carrier intends to “play”—and how.

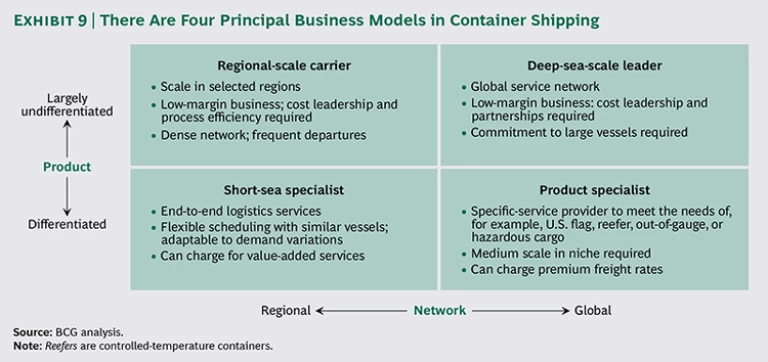

BCG’s assessment of the container-shipping industry shows four principal business models: regional scale, deep-sea scale, short-sea specialist, and product specialist. (See Exhibit 9.)

- Regional-scale carriers achieve sufficient size in a regional niche and customize their capabilities to regional needs while competing with deep-sea-scale carriers for cargo. However, thanks to their closer regional relationships and local knowledge, regional-scale carriers can compete against larger carriers in their market.

- Deep-sea-scale leaders offer a global service on high-volume trades and leverage their scale (large vessel sizes, network reach, and density) to get the lowest possible slot costs.

- Short-sea specialists take the regional-scale approach one step further, tailoring their services to the short-haul market through flexible scheduling while also deploying smaller vessels and providing value-added logistics services. They lack scale, but they differentiate their services enough to compete with larger global or regional carriers. Many even transport those companies’ short-haul cargo.

- Product specialists provide specific niche services such as refrigerated containers or out-of-gauge cargo, or they cater to U.S. flag requirements. They can, therefore, charge a premium for their services.

Some global carriers have combined several business models under different brands and somewhat autonomous organization setups. However, midsize carriers cannot be “everybody’s darling.” Given their limited scale and existing capabilities, they must develop a right-to-win business model that enables them to create a sustainable and competitive position in their respective market.

Building the Right Operating Model. Carriers must back their chosen business model with the right operating model. For example, the operating model spells out which processes the carrier will centralize or decentralize, which it will outsource or offshore, and what its cost structure will look like. By reconfiguring its operating model, a carrier in effect rewires how it delivers products and services to its customers.

For instance, to compete effectively on shorter trade routes in specific regions, some carriers set up standardized, automated processes to maximize efficiency combined with a low cost-to-serve. Others use tailored infrastructure—such as depots—as a platform for providing new value-added logistics services.

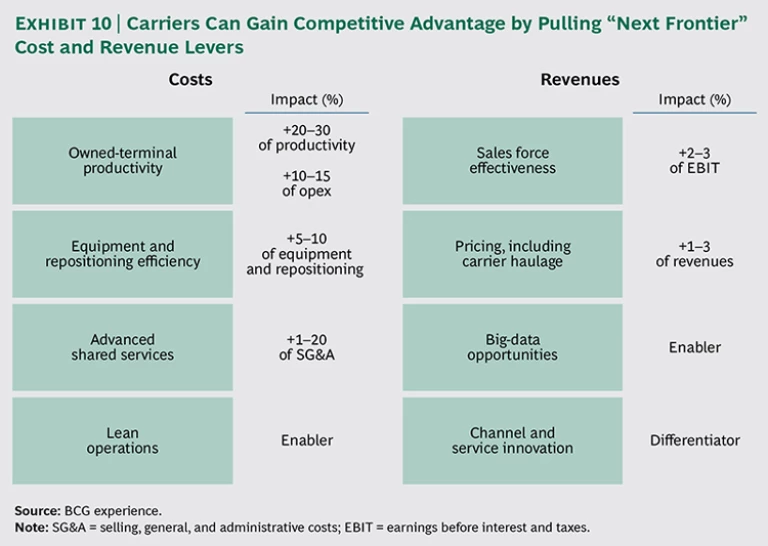

Having defined their business and operating models, carriers must then pursue “next frontier” cost and revenue levers to gain competitive advantage. (See Exhibit 10.)

- Cost Lever 1: Owned-Terminal Productivity. Many large carriers own or have interests in strategic terminals, whether gateway or transshipment hubs. Optimizing this critical infrastructure’s efficiency is vital for permanently reducing port stay time and, hence, bunker consumption. Generating additional peak productivity also improves network flexibility, enabling a carrier to weather potential delays and other disruptions. We have found that container terminals that adopt tools used in advanced asset-constrained manufacturing industries can boost quay crane productivity by up to 30 percent. They do this by reducing previously unrecorded performance issues such as tractor flow disruptions and shift change delays and by improving yard and stowage planning to maximize dual cycling and twin lifting. In addition, such programs help reduce terminal opex by up to 15 percent, through, for example, labor-planning reviews and optimization of maintenance cycles and spare-parts management.

- Cost Lever 2: Equipment and Repositioning Efficiency. There are plenty of cost reduction levers that carriers have yet to pull to reduce equipment costs and improve efficiency and repositioning along the entire equipment life cycle—from purchasing or leasing, operations, and maintenance to storage and disposal. For example, all carriers face significant challenges in equipment positioning. Container flows dictate where full and empty containers end up, and most flows are not balanced in opposing directions. Some of these imbalances stem from structural issues: some countries export more than they import. But there are carrier-specific imbalances as well. For instance, customers are scattered across port and inland destinations, and that can mean costly repositioning of containers. Our analysis indicates that up to 10 percent of carriers’ operating costs are related to flow adjustments, mostly for intermodal and terminal operators moving empty containers. Carriers could reduce these costs significantly by exchanging more equipment among themselves in locations with opposite demands. But to do so, carriers need to overcome their reservations about making such exchanges. Our experience with all 15 equipment-optimization levers—including procurement optimization, container inventory reduction, repositioning-cost minimization, and repair-planning improvement—shows that carriers can reduce equipment- and repositioning-related costs by 5 to 10 percent in the medium term.

- Cost Lever 3: Advanced Shared Services. Many carriers have started offshoring such basic functions as documentation and accounting to shared-service centers. We believe that carriers can drive this process further by offshoring virtually all mature and strategically less important operational, financial, and commercial processes to lower-cost shared-service centers. Furthermore, carriers should consider consolidating functions that require high-level skills (for example, stowage planning) to improve quality and reduce redundancies. The result could amount to savings of 10 to 20 percent on overall selling, general, and administrative costs.

- Cost Lever 4: Lean Operations. Carriers can further differentiate themselves by eradicating operational inefficiencies and waste, such as cargo renominations, rehandling, and minimization of port stay time. Some carriers have launched lean and Six Sigma programs that target such cost savings and process improvements, but few have realized the full potential in core operational processes. BCG’s lean-in-operations approach has enabled carriers to minimize waste and associated costs and to achieve significant efficiency gains. Lean and harmonized processes are also critical for strengthening a carrier’s internal capabilities and improving IT support, because they enable carriers to fully unlock the benefits provided by scale.

- Revenue Lever 1: Sales Force Effectiveness. Shipping-industry customers are increasingly savvy about their needs and the solutions and services available to them, and their procurement organizations are more sophisticated than ever before. Many carriers haven’t adapted to the changing environment, and they struggle with longer sales-cycle times, lower conversion rates, and less reliable forecasts. Clearly, carriers must enhance their sales-force effectiveness to acquire better cargo, optimize network flows, and enhance net profitability. Five practices are essential to this effort: targeting the most valuable markets, customers, and advantageous origin-destination pairs; optimizing deployment of sales force resources to targeted customers; maximizing the number of conversations with targeted customers to increase each rep’s number of “at bats”; engaging with customers in new ways to identify and deliver on business opportunities; and equipping salespeople with the tools, metrics, compensation, and training they need to excel at their jobs. Moreover, customers brought in by the sales force must be retained through flawless service. These practices can yield a 2 to 3 percent uplift in EBIT margins.

- Revenue Lever 2: Pricing, Including Carrier Haulage. Many carriers do not yet perceive pricing as a significant value lever. Key hurdles include decentralized pricing governance, insufficient analytical decision-making tools, and inefficient pricing processes. To take pricing to the next level, carriers must craft advanced pricing strategies for spot and contract cargo by, for example, developing dynamic pricing that adjusts freight rates according to projected utilization levels or by offering different booking classes, similar to airline industry practices. Carriers can also extract more value from carrier haulage pricing and surcharges. In our experience, advanced intermodal pricing can help transform the intermodal service from a cost center to a revenue generator. Today, many carriers take a one-size-fits-all approach to intermodal pricing, treating all customers with a cost recovery or cost-plus calculation, or—worse—providing all-in rates whereby the ocean freight subsidizes the intermodal expenses. A better approach would be to identify the customers that do not have their own intermodal capabilities and to charge premiums for the additional service. Experience shows that smarter pricing and carrier haulage can result in a 1 to 3 percent revenue boost.

- Revenue Lever 3: Big-Data Opportunities. Advances in data analytics and reporting solutions are providing carriers with unprecedented opportunities to link a wide variety of internal and external data and to generate actionable business insights from it. BCG’s speed-to-insight approach has helped carriers generate business value from big data in a quick three-to-four- month process rather than the typical multiyear journey. The key here is an iterative rollout, whereby carriers conduct pilot projects during which they prototype new approaches to data analysis before incorporating them into long-term solutions. For example, some carriers have tested tools to measure their agencies’ cargo-forecasting accuracy, drilling down to the level of individual customers. This has helped them optimize utilization levels and test dynamic pricing and has equipped sales reps to anticipate market developments and potential cargo shortfalls. On the operational side, big data can foster box-level cost transparency by enabling carriers to combine dispersed data from different systems and sensors to facilitate real-time operational decision making. Finally, carriers can use big data to help their salespeople uncover needs that customers don’t yet know they have. To accomplish this, companies need to combine external data sources (such as the Piers database of U.S. international trade) with internal customer information. Such advanced analytics help the sales team analyze customer needs early in the process and target previously unknown but attractive cargo.

- Revenue Lever 4: Channel and Service Innovation. Some industries have established neutral global distribution systems that are similar to the Amadeus system used by commercial airlines. By contrast, obtaining a freight rate directly from a carrier can be a cumbersome manual process through local sales reps, call centers, and key account managers. Current carrier-supported platforms, as well as carriers’ proprietary solutions, typically focus on supply chain activities, such as schedule inquiries, booking execution, and follow-up documentation. Developing a modern end-to-end customer interface and distribution system, including a real-time rate-inquiry element, could help carriers regain some of the ground lost to freight forwarders and the many emerging virtual platforms. It would also free up commercial capacity to focus on winning new customers rather than responding to rate inquiries.

The Right Organization, Team, and Culture

To successfully execute initiatives aimed at funding the journey and winning in the medium term, carriers must establish the right organization, team, and culture. As much as 50 to 75 percent of transformation change efforts fail, primarily because companies neglect these imperatives.

Organization. A BCG study found that while business complexity has increased sixfold since 1955, companies have responded by increasing operational complexity by a factor of 35 through the introduction of new procedures, processes, reporting layers, structures, and scorecards. The result? People in organizations spend more time managing work than doing work: they spend more time on activities that don’t add much business value.

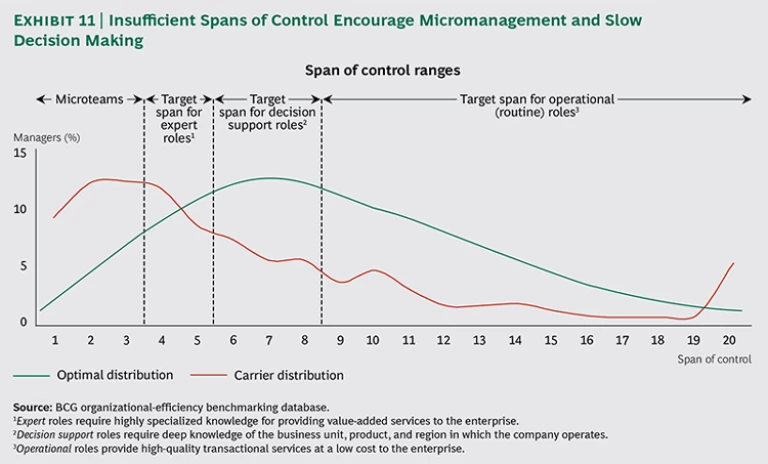

Data from BCG’s organizational-efficiency benchmark in shipping verifies this trend and reveals large variations in terms of organization size, complexity, and structure across carriers. Owing to less sophisticated systems and processes, certain functions (such as finance) have roughly three times the number of employees as their counterparts in adjacent transportation industries. Complexity worsens with an increase in the number of reporting layers and inappropriate spans of control. Indeed, many carriers have too many reporting layers. The resulting “belly fat” slows decision making and overburdens payrolls. On average, 34 percent of managers in the companies represented in our benchmarking database have spans of control with fewer than four people—many of them with just one direct report—which leads to efficiency-sapping micromanagement. (See Exhibit 11.)

Costly complexity from too many reporting layers and overly narrow spans of control can sabotage the execution of a transformation effort. With a plethora of ongoing projects and sluggish communication between the center and the front line, people lose focus, and the change program stumbles.

To avoid this situation, carriers need a streamlined organization with a flat reporting structure that is characterized by the fewest possible layers and managers whose spans of control are wide enough (depending on each function’s needs) to empower decision making and enhance agility. In addition, carriers can benefit by choosing the right business processes to centralize or to offshore to shared-service centers. The head office should focus on process design, structure, governance, and KPI definition. Activities common across regions can be bundled into a few centers to minimize costly duplication. Many mature processes, well beyond accounting and documentation, can be offshored. Meanwhile, regional offices should focus on target setting and performance management; individual sales offices, on executing mandates coming from the center and regional offices.

Team. Effective transformation teams embody a blend of traditional shipping backgrounds and fresh talent from outside the industry. Their leaders demonstrate commitment to the change journey and model the right behaviors to drive change from the front lines. To identify such leaders, carriers must consider candidates’ past performance, current readiness, and future potential on the basis of such criteria as knowledge of change, soft (people) skills, experience, motivation, and ability to cascade change through the organization. Such skills differ markedly from those required to manage day-to-day operations.

Culture. Our work with global shipping and other transportation companies shows that the best organizations also foster a performance culture in which individual and collective behavior supports execution of the company’s strategy and reinforces desired behaviors. Performance management (through the use of the right KPIs, rewards, and recognition programs) plays a critical role in building such a culture, as do training, clear decision rights, and career path and promotion policies.

In this regard, the shipping industry is fairly immature compared with the overall transportation industry. Furthermore, BCG’s organizational-efficiency benchmark in shipping shows that most shipping companies lack a harmonized set of KPIs across different functions, project teams, and regions. For instance, few shipping companies measure the value of their human-resources function using metrics such as ability to recruit and retain the best talent and to provide effective training. Moreover, although most of the companies in our database had defined sales targets and KPIs for their individual sales teams, the targets and indicators were not encouraging the right behaviors—including those called for by the companies’ transformation efforts.

In sum, the three-step holistic-transformation framework described above can help carriers begin to pull themselves from the vicious cycle they’ve been trapped in and start to create strong, sustained value instead of destroying it. Ultimately, such change programs may restore the companies to profitability and enable them to deliver returns above their cost of capital. But carriers stuck in the middle cannot stop there. To continue creating value in the long term, they need to climb the scale curve and forge new kinds of alliances.

Extracting More Value from Alliances

Carriers operate in a tough business in which customers care most about getting the lowest-possible freight rate. Economies of scale are a crucial aspect of reducing slot costs to enable competitiveness on rates. Our models show that, depending on the trade, relative vessel size, and cost level, carriers can typically achieve slot cost savings of 15 to 20 percent by doubling the size of vessels. Vessel-sharing agreements (VSAs) and firmer alliances let carriers jointly deploy the most economic vessels to serve specific trades, provide more departures in key ports, and achieve wider network coverage. Moreover, sharing spreads the utilization burden of larger vessels among more companies and clients, and carriers can, therefore, offer a good product at low cost.

The years 2013 and 2014 saw the forging of ever-larger alliances in the container-shipping industry: 16 of the top 20 carriers are now firmly associated with a large alliance, and only a few smaller and niche companies remain independent. In addition, the scope of such alliances has gradually increased and now covers all three east-west trades: Asia and Europe, transpacific, and transatlantic. Further expansion into intraregional trades (and feeder operations) or north-south trades such as Latin America could be a logical next step.

Why Alliances Instead of Real Consolidation?

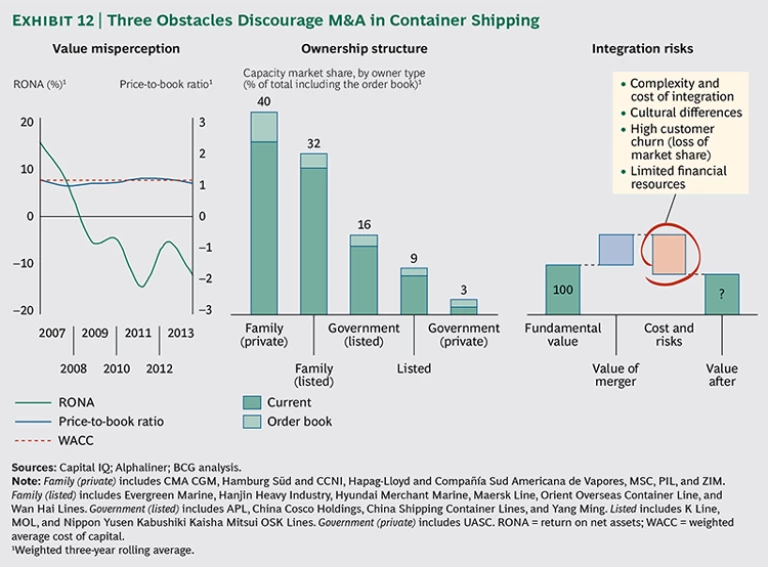

Alliances help carriers build scale, improve their offering, extend their network reach, and reduce costs. But one might wonder whether carriers could get the same benefits through M&A. The industry is ripe for more consolidation. Plus, M&A deals offer farther-reaching synergies in terms of streamlined organization structures and far less day-to-day operational complexity than is common among alliance partners. Moreover, M&A allows carriers to achieve commercial synergies in a consolidated entity, which is not legally permissible for alliances. In recent years, however, carriers have steered clear of larger M&A transactions for three reasons: value misperception, ownership structure, and integration risks. (See Exhibit 12.)

Value Misperception. Shipping-company valuations are still pegged to the “value of the steel” even though many companies are far from meeting their cost of capital or even achieving positive cash flows. Many are reluctant to correct the valuation of expensive assets they acquired before the recent economic crisis to reflect their current market value. Furthermore, considering the negative cash flows that many carriers will likely face for some time to come, current price-to-book ratios of about 1 scare away potential acquirers.

Ownership Structure. As much as 90 percent of the vessel capacity operated by the 20 largest carriers is family or government controlled. For both types of owners, decisions, behaviors, and priorities can be influenced by forces other than financial returns. For instance, most families are unwilling to loosen their grip on their companies. Meanwhile, governments often have sovereign and other interests in addition to interests in the carriers they own—for example, securing reliable import-export channels and jobs for citizens.

Integration Risks. Like other industries, the shipping industry is susceptible to postmerger integration (PMI) risks. These include the introduction of costly complexities into a combined entity’s operations—a likely situation, given the industry’s dispersed regional setups and heterogeneous processes. Cultural differences also present risks. Moreover, in the past, some large entities formed through acquisition experienced high customer churn due to service disruptions related to the integration.

Given the difficulties stemming from overstated valuations, ownership structure, and PMI risks, alliances provide a safer way for midsize carriers to achieve the scale required to compete in deep-sea or regional trades. The formation of alliances may also compensate for the current absence of consolidation in the industry, possibly providing more stability and serving as an intermediate step toward full integration. However, in their current form, alliances are leaving value on the table.

Leaving Value on the Table

In our 2012 industry report, we emphasized the need for carriers to get smarter about alliances if they wanted to reap the full potential of such arrangements. Today, the majority of alliances are still based on VSAs. Consequently, carriers have not yet unlocked the full value that these alliances promise. However, some regulatory filings that have already been approved outline key elements that could help alliances create more value for members. For example, the current agreements governing some midsize alliances include extensive provisions on levers for capturing additional scale benefits and synergies. Such levers include joint procurement—in categories such as terminals, intermodal services, and depots—and joint operations centers. Yet members of these alliances haven’t yet taken full advantage of most of these provisions.

Most alliances would face limited regulatory hurdles to activating these levers, given the current market fragmentation (commercial and pricing collaboration being the most notable exceptions). Claiming this value will be particularly important to midsize carriers continuing in the deep-sea trade.

A Better Way: Toward More Sophisticated Alliance Models

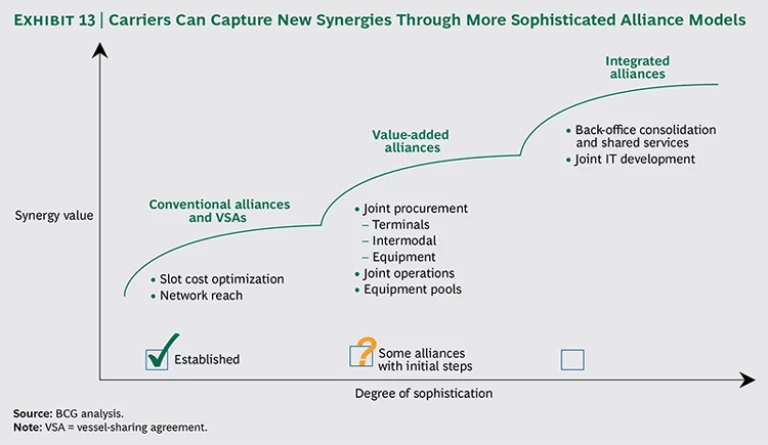

To extract more of the value that these arrangements offer, midsize carriers need to approach alliances in a new way. Transitioning from conventional alliances and VSAs to more sophisticated alliance models would constitute a good first step. (See Exhibit 13.) Although VSAs today focus on optimizing members’ slot costs and network reach, a value-added alliance model can unlock far more substantial value in the form of cost synergies gained through joint procurement, joint operations, and equipment pools. Integrated alliances can build on those gains, adding consolidated back-office functions and joint development of IT solutions. Of course, such tightly knit alliances aim to generate competitive advantage and value for the long run, because the partners will find it harder to separate from these arrangements than from the looser kinds of alliances.

To grasp the jump in value that more sophisticated alliances can produce, let’s examine critical elements in the value-added and integrated alliance models.

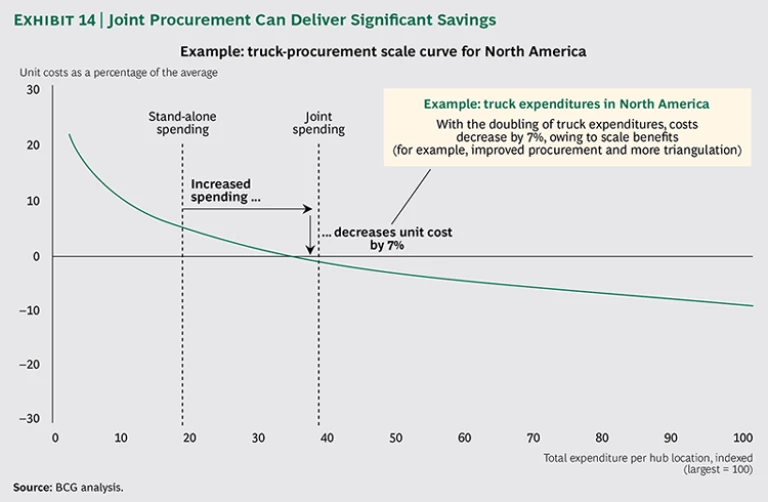

Joint Procurement. Alliances that use joint procurement can achieve substantial scale advantages in most major cost categories. Drawing on BCG’s SBI, which contains detailed cost data across all categories, we have calculated the full impact of scale advantages across different cost categories, cost positions, and regions. We analyzed data covering more than $30 billion in total annual spending of ten leading carriers. We found, for example, that if members of an alliance bundle their procurement of truck services in North America and double their total spending, truck unit costs can decrease by 7 percent (depending on spending, category type, and region). (See Exhibit 14.)

Joint Operations. By setting up an independent center with a mandate to fully manage operations for an alliance’s entire fleet, an alliance can optimize vessel deployment, eliminate redundant vessel-operations centers, and optimize unused capacity among partners. Instead of allocating vessels on a pro rata or similar basis, an alliance would be able to deploy the vessel best suited to specific trades regardless of who owned it or how it would be shared. The vessel network would, thus, work across silos instead of within individual carriers.

Equipment Pools. Alliances could reap additional benefits by pooling their equipment to optimize container repositioning with a much larger critical mass. Pooling equipment could further translate into lower overall equipment levels, owing to safety-stock-level reductions in depots. However, pooling has complications related to the exchange of sensitive commercial data and equipment prioritization. To manage these complications, carriers would need to implement effective platforms that would facilitate the exchange of sensitive data and equipment prioritization.

Back-Office Consolidation and Shared Services. Alliance members have already worked hard to build shared-service centers in critical regions. These could be integrated to provide common functions and tasks in one center that would handle, for example, documentation, customer service, finance, and HR activities. Thanks to the economies of scale and scope achievable through this approach, such centers can manage the tasks much better and at a lower cost than can an individual alliance member.

Joint IT Development. Annual costs of running IT systems typically constitute only about 1 percent of a carrier’s total expenses. But because of the lack of available third-party solutions, most carriers make large investments in the development of their own IT solutions for supporting the core processes needed to manage their operations. Today, most carriers make these investments independent of one another, in many respects, reinventing the wheel. Alliance members could share the investment burden by codeveloping more standardized, common applications.

The Size of the Prize

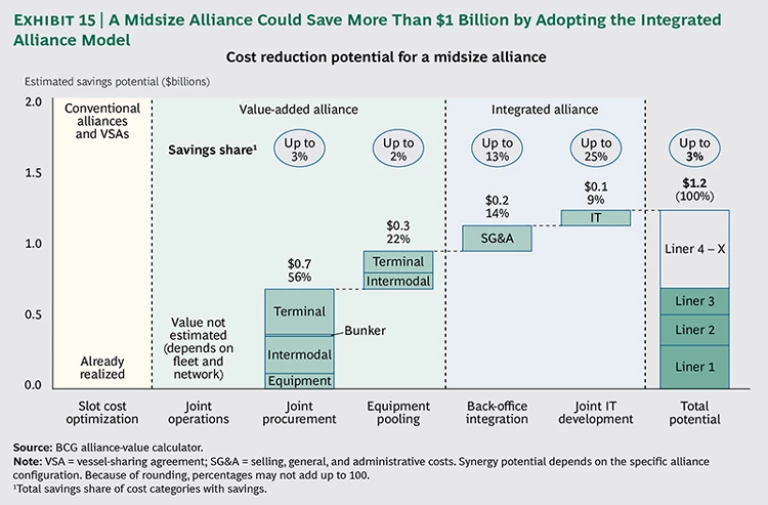

How big a prize can carriers expect if they transition to a more sophisticated alliance model? Using BCG’s CBI, we have developed estimates on the basis of hard cost facts. For example, our analysis suggests that if a midsize alliance were to be transformed from its current setup to the value-added alliance model, joint procurement and equipment pooling alone could deliver almost $1 billion in annual savings. Integrating back-office functions and establishing joint IT development through an integrated alliance model could add another $300 million in savings. The total annual savings could thus exceed the $1.2 billion that today constitutes roughly 3 percent of the alliance’s estimated operating expenses. (See Exhibit 15.) Although the alliance’s members probably will not realize the full extent of these savings in the near term, even a partial realization could move the needle toward more acceptable shareholder returns.

The transition to more sophisticated alliance models comes with challenges. For instance, midsize alliances may include as many as six members from different parts of the world—and disparate cultures. Such diversity can make it difficult for members to agree on critical matters, such as whether to establish joint procurement, who will make which decisions, and how new value will be shared. Finding the right strategic partners and establishing the right alliance operating model are critical for achieving alignment among members on these and other important matters.

Finding the Right Strategic Partners

To get a sophisticated alliance model to work, members must establish a good “fit” in four areas: strategy, culture, assets, and equity.

- Strategic Fit. Partners that have a good strategic fit share a similar operating model, trade footprint, and organization size—in terms of revenues, number of employees, and number of vessels. If partners differ considerably in size, the smaller ones may be left out of decision-making processes, while the larger ones may benefit more from procurement synergies.

- Cultural Fit. Alliance members must see each other as allies, and that requires trust. Cultural differences can foster mistrust, which can spawn behaviors that benefit particular members—but not the alliance overall—and prevent the alliance from achieving the best collective results.

- Asset Fit. Partners stand the best chance of capturing greater synergies if they share the same asset goals (for example, the ratio of owned to chartered vessels and their size), the same specifications needed to serve customers (such as reefer slots), and complementary terminal interests.

- Equity Fit. Partners have good equity fit when they have similar ownership structures, degree of financial strength (such as available funds for investments), and growth strategies. A financially stretched carrier may be less willing than its stronger partner to invest in the assets required to succeed in specific regions and trades.

To forge a value-added or integrated alliance with new partners, carriers may have to leave an existing alliance. Depending on the characteristics of the new partners, defecting could mean a temporary loss of or decrease in advantages enjoyed in the previous alliance. These include scale benefits (such as lower slot costs), network reach, and influence over other members’ activities. There are trade-offs with every choice, and carriers must weigh them carefully.

However, because many companies operate vessels of similar size in the different trades, defecting from a major alliance may not necessarily result in substantial slot-cost losses—especially if the new alliance obtains similar-size vessels. BCG analysis shows that most shifts to alternative alliance setups do not incur substantial slot-cost disadvantages owing to industry fragmentation and meager differences in average vessel size among alliances. For the most reasonable new alliances, the slot-cost disadvantage will amount to less than $100 million, which could be significantly lower than the potential benefits of more sophisticated alliance models.

Considering New Alliance Operating Models

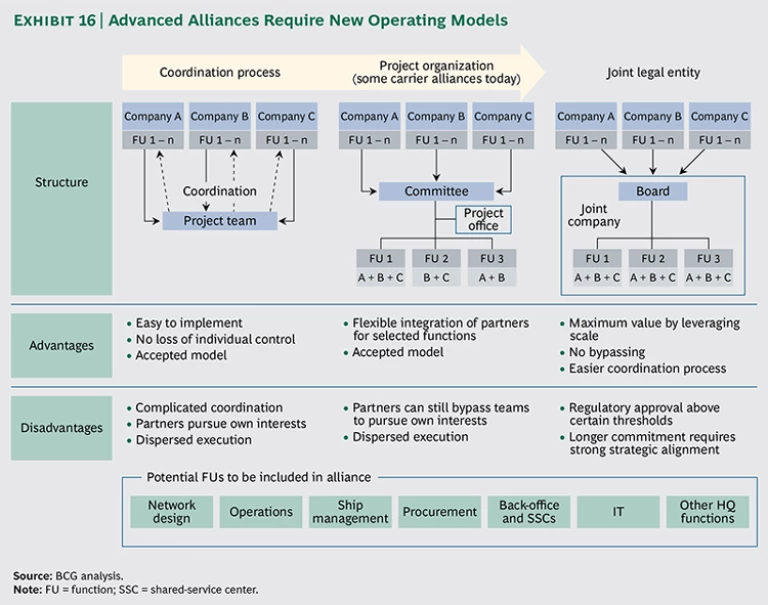

Adopting the value-added and integrated alliance models requires major change, as well as the definition of a new operating model. (See Exhibit 16.) Today, most alliances are managed through relatively simple information-coordination processes among the partners. In this setup, each member retains some control over each decision made. However, like managers in a siloed organization, alliance members tend to make decisions that support their own interests, not necessarily those of the alliance overall. Some alliances have set up committees and a project office to control functions such as network design and planning. But because the alliance members are still discrete entities with their own interests and authority, they can generate only limited collective value.

To fully capitalize on alliance opportunities, members need to shift away from the traditional coordination process that has a project team or the project organization using a separate committee and project office. Instead, members have to consider a joint legal entity that takes control of advanced functions including network design, operations, procurement, fleet management, and IT development. The structure of the joint legal entity can deliver important efficiencies, but adopting it requires strong strategic alignment among the partners as well as regulatory approval.

Our investigations with specialty lawyers and former European and U.S. maritime commissioners suggest that carriers face limited legal hurdles in building such operating models—provided that alliances don’t exceed certain size thresholds or distort competition. As described earlier, many elements of the value-added and integrated alliance models are already in place in some currently filed alliance agreements. Moreover, some regulations (such as the block exemption regulation in Europe) allow a wide range of synergy opportunities in alliances, including joint operations, equipment pools, and IT development. Still, carriers exploring these newer alliances should obtain expert legal advice and closely communicate with regulators in critical regions to develop an approach tailored to their situation.

As carriers move toward more sophisticated alliance models, the tightening of the bonds among them could presage a move toward consolidation in the industry through subsequent M&A activity. Indeed, the more advanced models should help alleviate the ownership reservations and limit PMI risks that are currently discouraging consolidation.

Ten Imperatives for Restoring Profitability

The much-anticipated recovery of the global container-shipping industry won’t likely happen anytime soon, owing to persistent challenges in the industry, including overcapacity and fragmentation. Many carriers have intensified their cost-cutting and transformation efforts to address these challenges, but these will probably not be enough to restore midsize carriers to attractive profit levels in the medium term. To lift their earnings and to return (or exceed) the cost of capital, they will need to intensify their transformation journey by implementing the three-step framework introduced in this report, including funding the journey, winning in the medium term, and establishing the right organization, team, and culture. Transitioning to more sophisticated alliance models can further help midsize global carriers create new value that could endure into the long term.

However, making these major internal and external changes will require an unprecedented degree of boldness and a willingness to venture into new frontiers of efficiency, collaboration, and, possibly, even consolidation. We believe that embracing the following ten imperatives can help carriers navigate the rough seas ahead.

- Define a clear path toward creating more value for shareholders and meeting (or exceeding) the cost of capital.

- Decide on a winning business model and build the capabilities needed to implement it.

- Incorporate the new, low-growth normal and declining freight rates into your strategy and business planning.

- Be selective when ordering new vessels, because every additional ship will further distort an already oversupplied market.

- Reap the full cost-reduction potential by giving operations more leverage when designing and running the global network.

- Enforce pricing discipline through advanced tools and processes that mitigate freight rate erosion.

- Flatten the organization and simplify reporting structures and accountabilities.

- Steer your company through the transformation with an activist program office.

- Exploit technology and business model innovation to break out of the vicious cycle.

- Reinvent your alliance and consider M&A to build the scale required for deep-sea trades.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dinesh Khanna, Seungwook Oh, Byung Nam Rhee, Tomer Tzur, Jesper Præstensgaard, Jihoon Kang, Mads Peter Langhorn, Sanjaya Mohottala, Yossi Arouch, Rüdiger Wolf, Mathias Thomsen, David Stone, Alexander Rasmussen, Johannes Schlingmeier, Johannes von Dungen, Iulia Tarata, Jonas Lorentzen, Dorota Korenkiewicz, Dustin Klimczak, Robert-Alexander Koch, and the team members of BCG’s Shipping Benchmarking Initiative.