The Danish company Maersk Group dates its founding to 1904, when ship captain Peter Mærsk Møller and his son A.P. Møller founded a shipping company. Today, Maersk is the world’s largest container-shipping company, with additional businesses in container terminals, shipping services, upstream oil and gas, and contract oil drilling. With annual revenues of nearly $50 billion, Maersk is Denmark’s largest company, representing roughly 14 percent of the country’s entire GDP. The company’s market capitalization is second only to that of pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk. Maersk is publicly traded on the Copenhagen stock exchange, but the majority of voting shares are owned by a foundation controlled by the founding family.

During the five-year period from 2010 through 2014 covered by this year’s Value Creators report, Maersk delivered an average annual TSR of 13.3 percent. That may seem modest when compared to the world’s top value creators, but for the company’s sector and peer group it represents remarkably strong performance. Keep in mind that during the past five years, the container-shipping industry has faced severe economic headwinds as a result of the collapse of global trade after the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent slow recovery. The sector has suffered from serious overcapacity, falling freight rates, and major price volatility. (See The Transformation Imperative in Container Shipping: Mastering the Next Big Wave, BCG report, March 2015.) And the recent drop in oil prices, although beneficial in the short term for Maersk’s shipping business, has had a major negative impact on its oil and oil-services businesses.

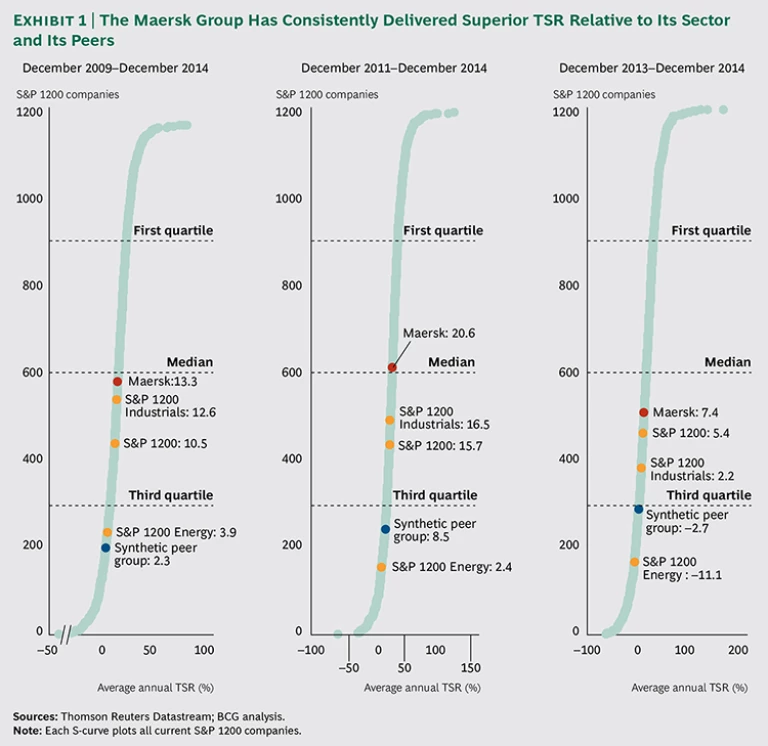

In the past few years, however, Maersk has undertaken a major transformation of its value-creation strategy, which has allowed the company to successfully navigate this turbulence, improve its value-creation performance, and outperform its peers. We compared Maersk’s TSR performance during three periods (comprising five years, three years, and one year) with the relevant market indices and with a synthetic peer group that mirrors the company’s current business mix. (See Exhibit 1.) Not only has Maersk consistently delivered above-average TSR relative to these benchmarks, but it has also, over the five-year period, delivered TSR nearly six times greater than its peer group.

Confronting a Crisis

In 2007, not long after the company’s centennial birthday, Nils Andersen joined Maersk as the fourth CEO in the company’s history (and only the second who was not a family member). At the time, Maersk was coming off a period of extremely strong earnings growth owing to the massive expansion in worldwide trade associated with globalization and to the company’s major oil concessions, located primarily in Denmark and Qatar. From 2001 to 2008, Maersk more than tripled its revenues.

What Andersen didn’t know when he joined the company was that all this was about to change. Not long after he became CEO, Maersk was hit with two major reversals that sent its earnings and its share price reeling. The first was the global financial crisis. The breakdown in the global credit system in 2008 led to a general collapse of world trade. By the beginning of 2010, more than 10 percent of container-shipping capacity worldwide was idle. The resulting overcapacity wreaked havoc with industry pricing and caused Maersk’s revenues to decline precipitously—by 20 percent, about $10 billion, in 2009—forcing the company to post a loss for the first time in its 100-year history.

As if that weren’t bad enough, there were emerging problems in Maersk’s oil business. Although the business was highly profitable, the company had been exploiting its reserves for years and not investing in the future. Maersk had one of the lowest reserve-to-production ratios in the industry. In order to sustain the business, massive new investments were necessary.

The combination of the enormous cutback in global trade as a result of the financial crisis and declining investor expectations because of the issues in Maersk’s oil business caused Maersk’s share price to plummet. From the time Andersen joined the company, in 2007, to the end of 2009, the company lost two-thirds of its market value.

Focusing on Value

The first challenge that Anderson and his team faced was to stop the bleeding. From 2008 to 2010, Maersk inaugurated a series of major cost-cutting initiatives, recouping some $3 billion. But Maersk didn’t focus only on cutting expenses. The company also engaged in a systematic effort to simplify the business, increase transparency and accountability, and get managers to concentrate on creating operational value rather than merely managing assets.

For a variety of reasons, Maersk had an organizational structure that made it extremely difficult for not only investors but also the company’s managers to understand how its various businesses were performing and whether or not they were creating value. For one thing, Maersk’s shipping-related operations were integrated: container shipping, the management of terminals, and logistics services—quite different businesses and each with its own competitive dynamics—were combined in the same organization. Not only did this hinder transparency about the performance results and investment needs of the various segments, but it also meant that most of management’s attention and the lion’s share of capital investment were focused on the container-shipping business. As a result of this lack of transparency and poor capital allocation, Maersk’s shares suffered from a substantial conglomerate discount in the capital markets—foregone equity value that analysts estimated as equal to roughly 25 percent of the company’s market capitalization.

Maersk’s senior-management team took three steps to start addressing these problems. First, it created a small but activist corporate center, separate from the traditional shipping business, in order to ensure a targeted focus on each of the businesses in the group’s portfolio. Second, the team increased the transparency of results, with a focus on getting each business to operational excellence compared with relevant peer groups—part of an effort to develop a more value-focused “operator mind-set” in what had been traditional asset-driven industries. Finally, the team explicitly defined the strategic roles of each business unit, clarifying where to manage for value, where to invest for growth, what to divest, and what to fix.

These moves allowed Maersk to significantly increase the underlying operating performance of its businesses. Today, the majority of Maersk’s businesses are best in class or in the top quartile (as measured by return on capital employed) when compared with their relevant peers.

Restructuring the Portfolio

With the clarity and accountability of the various businesses in the group improved, the next step in the transformation of Maersk’s value-creation strategy was to systematically restructure the group’s portfolio. Over the years, the company had acquired positions in a far-flung range of businesses outside its core shipping and energy businesses. For instance, it owned a majority stake in Dansk Supermarked, a large Northern European retail-grocery chain, and a 20 percent stake in Danske Bank, the second largest bank in the Nordic region.

The new portfolio strategy had three components. The first was a series of divestments. Some of the businesses sold were marginal non-value-adding assets. Others, like Dansk Supermarked (in which Maersk retained a small minority stake) and Danske Bank, were large, well-performing businesses but outside Maersk’s core strategic focus. In some cases, the proceeds from these sales were reinvested in Maersk’s core businesses; in others, they were returned directly to the company’s shareholders. These moves were made in a way that both built shareholder value for Maersk and set up the divested businesses for long-term success.

At the same time, Maersk proceeded with the second major step of the new portfolio strategy—the reorganization of its remaining operations into four core business units, each with ambitions for global leadership: Maersk Line, the world’s largest container-shipping company; APM Terminals, the world’s largest container-terminals company; Maersk Oil, a midsize global upstream oil-and-gas company; and Maersk Drilling, a leading drilling operator. Moreover, a cluster of midsize shipping-related businesses with promising platforms for future growth were taken out of the other businesses and grouped in a business unit of their own called APM Shipping Services. That way, they would get the attention necessary to develop further.

The third component of the portfolio strategy was equally important. The company developed new rules for allocating capital across its five new business units. Allocation was determined on the basis of each unit’s performance, outlook, and specific role in the overall portfolio. These new rules have had a major impact on how Maersk allocates its capital to the businesses that are most attractive over the long term.

Becoming More Investor Friendly

Creating a more focused and transparent portfolio has gone a long way toward making Maersk more investor friendly. So has a major shift in the company’s financial policies.

In February 2013, Maersk took advantage of the cash accumulating on its balance sheet because of its value-based initiatives, balance sheet trimming, and sales of noncore assets to announce a 20 percent increase in its dividend—and then, in February 2014, the company announced an additional increase of 17 percent. In April 2014, Maersk announced a five-way share split to improve liquidity and make it easier for investors to buy and sell stock. Four months later, the company announced the first share buyback in its history—a program of $1 billion to be executed over the subsequent year. And recently, the company announced a one-time special dividend associated with its divestment of Danske Bank.

All these moves helped the company shift its investment approach from a traditional focus on pure growth to one that emphasizes balanced growth at a reasonable price. The new focus attracted an investor base that was more aligned to the company’s new value-creation strategy.

Breaking Away from the Pack

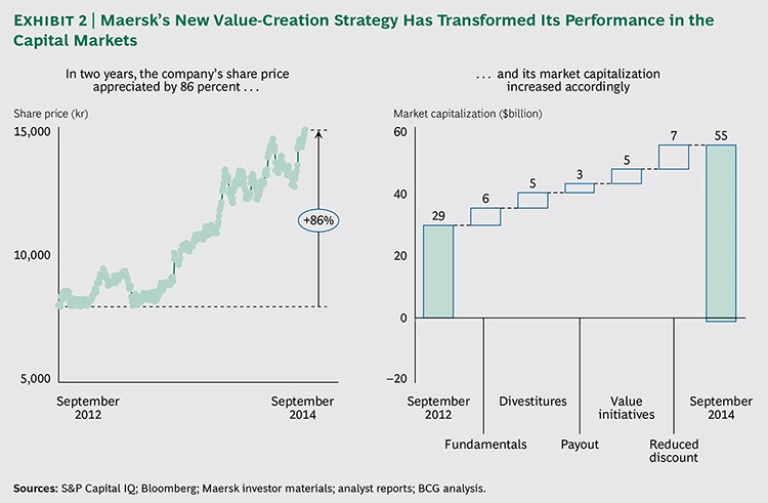

This combination of initiatives has had an extraordinary impact on Maersk’s stock price and market capitalization. In the two years following the introduction of the new value-creation strategy, the company’s stock price grew by 86 percent, and its market capitalization increased by $26 billion. (See Exhibit 2.) We estimate that nearly three-quarters of this increase can be attributed to the various moves the company has made—improvements in fundamental value, the divestment program, the increase in cash payout, and the value-based initiatives associated with more transparent metrics and a more focused portfolio. The remaining amount is the result of the elimination of the company’s conglomerate discount as investors have responded favorably to Maersk’s new strategy and purchased the company’s stock.

Today, Maersk is a far more efficient and powerful value creator than it was five years ago, despite the challenges facing its core industries. A clear sign of this change: in 2014, the combination of an improved business climate, operational improvement, and proceeds from divestitures allowed the company to grow its net profit by 37 percent—to $5.2 billion—despite the fact that net revenue remained flat compared with the previous year.

No doubt, the future will bring new challenges. The container-shipping sector remains plagued by overcapacity and a decline in freight rates. And the company’s oil business remains subscale compared with the industry’s giants. Now that Maersk has created a more stable platform for value creation, it will need to find new ways to improve margins and asset productivity while generating growth in what remain extremely competitive and capital-intensive businesses.

“The macroeconomic environment remains volatile,” says Maersk CEO Nils Andersen. “But the many change programs that we implemented in response to the financial crisis have helped us create a more agile organization. We now have a group of competitive business units and a financial strength that positions us well for the future. We are on an exciting journey and will continue to invest in growth and create value for our customers and shareholders—regardless of whatever turbulence lies ahead.”