C oded by an unknown hacker, germinating in the netherworld of cypherpunks, Bitcoin was not discovered by the business mainstream until 2015. Just as punk rock was repackaged as new wave, so was Bitcoin domesticated into blockchain. It burst on to the popular imagination and the conference circuit. Visionary Don Tapscott affirmed, “I’ve never seen a technology that I thought had greater potential for humanity.” CEOs pointedly asked whether this was yet another disruptive technology. Their subordinates were set to investigate how it might work. And they found that it is all rather complicated.

Hints of disillusion. Time, perhaps, for some strategic analysis.

The truly disruptive technical advances of the past decades, the PC and the internet, had something in common. They wasted a newly cheap resource—computing power and bandwidth, respectively—to do something radically new. Digital tokens and blockchains , two distinct but complementary technologies, waste cheap storage to give data the continuity of real-world assets. Bitcoin is just the first application. The technologies are far from mature, but if scalability limitations are overcome, they will have long-term disruptive potential in complex transaction networks such as trade, health care, and the Internet of Things. And it is by no means obvious that traditional intermediaries will be able to control them.

This essay outlines how the economics of transaction costs and trust could be reshaped by tokens and blockchains and by the stacked architecture on which they are built. The aim is not to prescribe exactly what leaders should do (every business is unique, and the devil is in the details) but to provide a strategic context to help executives frame the right questions. For example:

- Which aspects of my organization are vulnerable to disintermediation and how likely is it to happen?

- Where likely, how do I need to rethink and reshape my existing business—before others do it for me?

- Where can I take advantage of blockchain-enabled digital continuity to build new offerings and business models?

- Where blockchain-based solutions are advantageous, should I go it alone or collaborate for decisive scale?

To begin at the beginning...

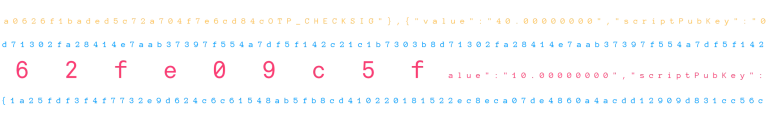

In the winter of 2014, Ukraine was on the brink of revolution. Protesters in Kiev held signs for the television cameras asking for money. (See image below.) The signs bore a QR code that allowed donors to send bitcoin to the protest movement. Thousands around the world pointed their cellphone cameras at the on-screen video and made donations with literally three clicks. The transactions were communicated in 20 seconds and confirmed within ten minutes at a cost of a fraction of a cent per dollar. They were anonymous: the government could not monitor them, and the recipients did not know whom to thank.

A donor could have made the same gift through the banking system, but that would have required detailed (and politically compromising) information about the recipient’s bank account, if he or she had one. It would have cost a commission of 10% or more, and taken three or four days to complete. PayPal, of course, would have been quicker and cheaper but was banned by the Ukrainian government. Paying with bitcoin was direct, anonymous, and irrevocable—like a sympathetic onlooker crossing Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the central square in Kiev, and dropping a couple of hryvnia into a plastic cup.

That is not just a figure of speech. A bitcoin is a digital bearer instrument: ownership and control are the

Some libertarians see bitcoins as “digital gold”: the incorruptible global currency that will ultimately replace the fiat currencies manufactured and debased at whim by central and commercial bankers. But as JPMorgan Chase CEO, Jamie Dimon, has vigorously pointed out, if Bitcoin came anywhere near to supplanting conventional currencies, central bankers would almost certainly intervene

Digital tokens and Blockchains, two distinct but complementary technologies, waste cheap storage to give data the continuity of real-world assets. Bitcoin is just the first application.

From a strategic point of view, Bitcoin’s importance is less as a currency and more as the early manifestation of its two underlying technologies: token (in this case, bitcoin) and blockchain. A token need not be a digital coin; it can be any kind of digital asset or any digital representation of a

How Bitcoin Works

How Bitcoin Works

- Bitcoins are digital tokens whose authenticity can be proved because they document their own ancestry.

- A blockchain is an online ledger that proves that a token has not been spent twice.

- Thousands of specialized computers operated by Bitcoin “miners” maintain the blockchain. These miners ensure the integrity of each new “block” by competing to solve an arbitrary computational task, making the cost of corrupting the blockchain practically insurmountable.

READ THE ARTICLE

The possibilities extend far beyond financial services, to supply chain documentation, land registries, health records, microtransactions, and smart contracts among billions of intelligent devices worldwide.

Venture funds and technology companies have committed over $1 billion to using these technologies to disrupt whole industries—or maybe to selling themselves and their services to incumbents to forestall such disruptions.

So what principles of economics and strategy will govern this brave new world?

Blockchain and digital tokens deliberately waste storage, which is cheap, to create something new that is valuable. This is actually the third chapter in an old story. Over the past 50 years, the information revolution has been propelled by exponential advances in the cost, speed, and capacity of three functions: computing, communication, and

PCs were less efficient than mainframes, but they gave end users greater control. PCs disrupted the mainframe industry. The internet was vastly less efficient than hierarchically switched telecommunications architecture, but it offered robustness and shifted the locus of innovation to the periphery. The internet disrupted everything.

Memory and storage are now following that same pattern. With cost per terabyte in free fall, the first response is to accumulate more data—hence, big data. But what can you create if you waste storage? Bitcoin, for one thing. The Bitcoin blockchain provides an inviolable record of each bitcoin’s history at the cost of storing each transaction record 5,700 times over.

Thus blockchain is the disruptive technology for storage, as the PC was for computation and the internet for communication. It is the last response to the transformative power of the

But what exactly is achieved by wasting storage?

Digital tokens such as bitcoin waste storage in massively duplicative blockchains to create virtual continuity. This is the fundamental breakthrough. Continuity—outside the domain of quantum physics—is a universal property of the physical world. If I pass an object behind my back, you can be reasonably sure that what reappears in my left hand is what disappeared from my right. Continuity permits identity of both things and people; it permits property because a continuously identified thing can be owned by a continuously identifiable person. It therefore permits transactions—transfers of property. It permits

But in the virtual world, there is no continuity. There is no guarantee—indeed, generally no meaning in saying—that a string of data is an original as opposed to a copy. Neither an object nor a person has identity. The old joke: on the internet nobody knows you're a dog. In many contexts, of course, that is a desirable feature. It lowers the cost of broadcasting and relaying information to near zero. But absent continuity, there is no peer-to-peer basis for identity, ownership, transactions, trust, or contracts.

Where the parties have a prior real-world relationship, they can establish a virtual equivalent directly through encryption. But otherwise, the world addresses the lack of virtual continuity through intermediaries. I have a real-world relationship with my bank, for example, you have a real-world relationship with yours, and the banks have real-world relationships with one another. Collectively, intermediaries (of which banks are just one type) guarantee our respective virtual identities and mediate our transactions.

The technologies of token and Blockchain endow data with continuity: they make the virtual real.

There are two problems. When there is just one intermediary, it will be a monopolist, which—if profit maximizing—will underinvest, overprice, and appropriate most of the value. But if instead the market is competitive, the intermediaries themselves require intermediation. In the multilayered system of international remittances, a money transfer to Kiev generates multiple transactions, delays, duplicated effort, and errors.

Bitcoin demonstrates the revolutionary potential of tokens and blockchains. As explained in the sidebar , it establishes continuity between two sequential transactions, say X and Y. Although it is just a string of numbers, the structure of the bitcoin—the token—guarantees its "ancestry": the coin in the earlier transaction X is the only “parent” of transaction Y. The authenticity of the coin can therefore be proved by tracing it back to its original mining.

And the blockchain guarantees "inheritance": the coin in the later transaction Y is the only “child” of transaction X. The coin cannot be spent twice. So the two aspects of Bitcoin technology together waste storage in order to create virtual continuity. Virtual continuity enables digital identity, ownership, transactions, and trust—and contracts and markets—among parties with no prior relationship and without intermediaries.

Seven Possible Killer Apps for Blockchain and Digital Tokens

Seven Possible Killer Apps for Blockchain and Digital Tokens

- Transacting on the Internet of Things

- Transforming the economics of digital content

- Making supply chains cheap and transparent

- Reforming land registries

- Guaranteeing digital identities

- Streamlining health care and revolutionizing research

- Minting digital fiat currency

The technology is potentially disruptive to all virtual intermediaries. Its disruptiveness is proportional to the cost, complexity, and degree of transaction duplication in the current system of intermediation.

Virtual continuity leads to one final symmetry. Recent technology waves—notably the Internet of Things, the proliferation of smart mobile devices, and augmented reality—directly endow physical objects with information and intelligence: they make the real virtual. The technologies of token and blockchain, conversely, endow data with continuity: they make the virtual real. When the real and the virtual converge, it is as if our world and our map of the world become the

Bitcoin has a stacked architecture that serves as the model and template for all other tokens and blockchains. A stack is a set of interoperable modules arranged in a hierarchy. Upper-level functions depend on lower-level functions, but not the reverse. General-purpose functions needing scale and reliability reside at the bottom of the stack (the infrastructure), while functions benefiting more from customization, experimentation, and innovation occupy the

With Bitcoin, the economics of each layer are radically different.

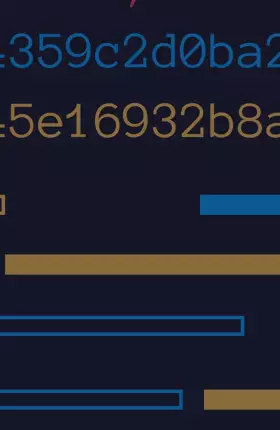

Blockchain

At the bottom of the stack is the Bitcoin blockchain: a database of all transactions, grouped into “blocks” and replicated across thousands of “nodes.” It is monolithic and scale sensitive (there is only one), and it becomes more reliable and robust as the number of nodes (currently 5,700) and the number of blocks (currently 430,000) continue to grow. Physically, these nodes are racks of dedicated computing devices, operated in data centers owned by so-called mining pools and concentrated mainly in China. Mining is a for-profit, commodity business.

Protocol

The Bitcoin protocol—its “operating system”—sits on top of the blockchain. This is free, open-source software, maintained by the Bitcoin Core team. Like Linux, it has the strengths of the open-source “business model”: rigorous code testing by all comers, rapid improvement cycles, and trust in the collective product because nobody owns it. It also has the model's weakness: the difficulty of making strategic choices by consensus.

Tokens

Bitcoins themselves are the next layer. They are tokens that are exchanged within the system and minted by miners (the network of nodes that validate transactions) as a reward for validating transactions. Like any medium of exchange, the tokens have value only because people think that other people think they have value. The first known bitcoin purchase occurred in 2010, when Hacker Laszlo Hanyecz bought a couple of Papa John’s pizzas with 10,000 freshly mined bitcoins. Today those bitcoins are worth more than $6 million.

Applications and Services

Applications and services make up the top layer and consist of “wallets” (software to hold and manage bitcoins on a smartphone or computer); exchanges that convert bitcoins to and from fiat currency; and information services. There are hundreds of such products and services, chiefly developed by startup companies.

The bottom of the stack, the Bitcoin blockchain, is extraordinarily secure. The total value of all bitcoin—some $10 billion—is a sufficiently rich honeypot to have tempted the best hackers in the world, yet the blockchain has never been successfully attacked. The top of the stack is another story, with claims of incompetence and criminality circulating around such well-known failures as Mt Gox and Silk Road. But the beauty of stacked architecture is that the moral and economic frailty at the top does not compromise the revolutionary robustness at the bottom.

As shown in the exhibit above, this stacked architecture defines the recombinatorial framework within which new currencies, new services, and entirely new concepts have been developed.

Colored Coins

Colored coins are top-of-stack innovations that exploit a blank field within each bitcoin to record unrelated data. The UK-based company Everledger, for instance, initially leveraged bitcoins to put “bling on the blockchain” by recording some 40 unique, laser-read identifiers of a diamond, providing proof of provenance and ownership. The bitcoin was not used to buy the diamond, just to create an inviolable record of the transfer of a specific authenticated stone. The same approach could be used to track any valuable asset with a complex

Altcoin

Altcoins borrow most or all of the Bitcoin protocol to create a separate token with its own stack. Many are exotically named jokes or Ponzi schemes: BaconBitsCoin (symbol: YUM), Kimdotcoin (KOIN), and Zombiecoin (ZMB), among others. However, some are more ambitious tweaks on the Bitcoin protocol. Litecoin, for example, is designed to produce blocks at a faster rate and with less computation than Bitcoin, and Monero pools transactions to prevent even pseudonymous tracing of payments.

Ethereum

Ethereum is an entirely new stack, which only a year after its launch, in July 2015, had a market value of nearly $1 billion. Many call it Bitcoin 2.0. Ethereum has its own blockchain and token (ether), and a protocol that supports not just payments but programmable transactions: “smart contracts” that are executed in code,

Permissioned Blockchains

Permissioned blockchains deviate substantially from the open Bitcoin paradigm, restricting certain roles or access to a club of participants, typically financial institutions. Only members are variously allowed to inspect the blockchain, engage in transactions, and operate as a processing node. Permissioned blockchains allow transactions to be written in legal language as well as in computer code; they also enable regulatory review. Today they are only at the proof-of-concept stage, but consortia such as R3 CEV in banking and many financial technology companies are focused on making permissioned blockchains a reality, especially for clearing and settling transactions in securities and foreign exchange.

Distributed ledgers are often described as “trustless” systems, but that is not quite right. More precisely, their locus of trust moves to the periphery.

When Everledger certifies a diamond, you know with blockchain-level certainty that someone possessing Everledger’s private key posted certain data on a certain date. But you still have to trust Everledger. Everledger therefore relies on a global network of industry-respected certification houses to authenticate

This leads to what we might term a Coasean theory of blockchains. Ronald Coase famously posited that corporations exist to economize on the transaction costs of markets. But when some degree of scale is reached, organizational complexity overwhelms. The optimal size of the company, according to Coase, is therefore the point at which the incremental benefit from transaction cost savings is offset by the incremental cost of complexity.

Blockchains similarly exist to economize on transaction costs: they protect a common database from failure or attack; they eliminate duplicate record keeping and associated delays and errors; and they convey trust transitively across the network. But the larger or more comprehensive the blockchain, the less trustworthy is the data entered by the least trustworthy member. Thus, the optimal size of a blockchain is determined by the tradeoff between transaction costs, which improve with scale, and peripheral trust, which deteriorates.

This is not mere theory. One of the most scrutinized uses of a blockchain is for the clearing and settlement of securities transactions, currently a complex network of brokers, custodian banks, stock transfer agents, regulators, and depositories. A single transfer can require a dozen intermediary transactions, and typically takes three days. Some 20% generate errors, which must be corrected by hand.

With a blockchain, two trading parties could read and write to a common, trusted, and error-free database. The transaction could be written in legal language as well as in computer code, so that the data exchange itself is the settlement. And it could be visible to regulators but not to other institutions. This is the concept behind Corda, a permissioned blockchain protocol under development by the R3 CEV consortium. It would eliminate bilateral errors and perhaps be cheaper than modernizing existing settlement platforms—the focus is on efficiency, not disruption.

But why stop there? The brokers (as agents of the buyer and seller) could trade on a larger blockchain to disintermediate the custodians, thereby further reducing total transaction costs. Institutions issuing securities, such as corporations and municipalities, could issue them directly onto the blockchain, thereby disintermediating their stock transfer agents.

What limits these more ambitious solutions is peripheral trust. Some 50 regulated global banks might have sufficient reason to trust one another’s honesty and competence. But for hundreds of brokers and thousands of issuing institutions, trust would be much, much harder to achieve. Hence the tradeoff between transaction costs and peripheral trust.

One can imagine a permissioned securities blockchain starting small but evolving to progressively larger scale and lower costs, as methods are developed to qualify the trustworthiness of additional participants. But there is a radical, if speculative, alternative: significant functions currently performed by “securities” could be performed by new, deconstructed smart contracts that are denominated in tokens native to some blockchain.

For those contracts, peripheral trust would be a lesser constraint, perhaps irrelevant. Such a blockchain would disrupt the club of trusting intermediaries, directly connecting the principals who create, buy, and sell the contracts. “Securities trades” would then be as fast, cheap, and secure as Bitcoin payments. And a big piece of the financial services industry would disappear.

Within most transaction networks, the larger a common blockchain, the lower the transaction costs but the less trusted the parties at its periphery. These and other scale economics are constrained by a more narrowly technical set of issues: the blockchain’s scalability.

Scale economics involve more than just balancing size and trust. There are four other mechanisms:

- The larger the number of nodes and the greater the height of the blockchain, the more secure are the recorded transactions. This gives established blockchains (notably those for Bitcoin and Ethereum) an advantage over smaller and newer alternatives—not just in payments but in any application that can be built on these blockchains.

- The larger the dollar volume of digital coins in circulation, the more liquid the currency and, probably, the more stable its exchange rate. This again favors established coins (such as bitcoin and ether) over startups. But more important, if a digital coin were to reach critical mass, it would become acceptable as a medium of exchange and a store of value in the economy at large, and a big piece of its associated transaction costs—the cost of trading into and then out of the coin—would disappear.

- A single compelling killer app can pull through an entire ecosystem of associated innovations and create a network effect at both the top and bottom of the stack. However, one of the striking features of the blockchain landscape is that no killer app has yet emerged. Bitcoin, the currency, appears to be entering the flatter part of its S-curve (daily transaction volume has grown by only a third in the past 12 months), and The DAO, which many thought was the killer app for Ethereum, has collapsed.

- The larger the blockchain and the more heterogeneous its participants, the more politically complex is the challenge of setting strategy. In permissioned chains, consortium management among members that otherwise compete with one another becomes critical. (Banks, in particular, have a checkered history of managing industry collaborations.) In permissionless chains, the challenge is to formulate and execute a technology roadmap in the face of the conflicting priorities of open-source coders, miners, and commercial developers. With digital currencies, conflicts escalate as the dollar value of the coins owned by some of these parties steadily grows. And open entry implies open exit: absent proprietary intellectual property, dissatisfied coders—convinced that they know better—can fork the code and steal the growth as well as the limelight.

Besides issues of business scale, there are huge challenges in technical scalability.

If Blockchains have a serious future, they must overcome current scalability roadblocks.

Currently, Bitcoin can handle 3 to 5 transactions per second and Ethereum 15 to 25. But the interbank Visa system handles 2,500. So if blockchains have a serious future, they must overcome current scalability roadblocks. Bitcoin’s capacity limit is dictated by the fixed rate at which blocks are created and the maximum block size. Faster block creation, it is feared, would destabilize validation, since a rogue chain could propagate faster than the consensus mechanism chasing it across the network could disown it. And larger block size would intensify economies of scale in mining, driving consolidation and making the validation system more vulnerable to collusion. (Already, 58% of the hashpower is held by four Chinese

Moreover, the deliberate inefficiencies of Bitcoin and Ethereum will eventually impose practical limits. Nodes can create a block only by solving a very arduous and arbitrary computation called proof-of-work (for each block, 10,000 terahashes). This inefficiency secures the network by massively escalating the cost of rewriting the blockchain. But bitcoin mining already consumes as much electricity as a US city of 280,000, and by one estimate, as much as Denmark will consume

The broad components of a scalability solution are widely recognized but have not as yet been implemented:

Proof-of-Stake

Under this protocol, a string of blocks is deemed valid only if the nodes creating it demonstrate sufficient ownership of the asset represented by the token to give them a compelling motive not to subvert its value. Proof-of-stake would radically reduce computing and transaction costs, enabling blockchains to facilitate much smaller transactions.

Channels

Channels are another layer in the stack. A subgroup of parties transacts directly but commits only a small fraction of transaction data to the main blockchain. Channels can thus proliferate without burdening the main blockchain and while still enjoying some of its security. There are many variants on this idea, such as the proposed Lightning Network for Bitcoin.

Sidechains

Closely related to channels, sidechains are blockchains in their own right. They create and destroy their internal token as a mirror of a transaction that immobilizes an equivalent on the main chain. This effectively allows users to move tokens from the main chain to sidechains and back again. The sidechain can operate on any principle whatsoever: lower security for minuscule transactions, fast block creation, smart contracts. It can even be a closed, permissioned chain.

Sharding

This is an approach that preserves a single global blockchain, but not all nodes validate all transactions. It sacrifices a measure of security for the benefits of scalability.

These developments are at the cutting edge of blockchain research and experimentation. The Bitcoin Core leadership is moving cautiously in these directions, as befits a blockchain advantaged for its security. The Ethereum developer community is moving much faster: the 2017 Release 2.0, code-named Serenity, will be explicitly built on all four design principles.

But startups with no legacy to protect are trying to beat established blockchains to the punch with the right combination of these principles. They may build on existing Bitcoin or Ethereum code and currency, or they could start afresh. The pieces are largely known, but the world is still waiting for the killer combination, the killer app.

There are five broad principles that will shape strategy for token and blockchain technologies.

1. BLOCKCHAIN STRATEGY IS MORE ABOUT COLLABORATING THAN COMPETING. It makes sense to expend resources on digital tokens and blockchains only when multiple entities are transacting at high cost and with imperfect trust. Therefore, the implementation opportunity presents itself to the entire transaction network, not to an individual participant. Global enterprise technology companies are investing to build alliances among their customers that could underpin transaction platforms in fragmented industries such as health care and international trade. Hundreds of Silicon Valley startups are focused on the same goal, or at least on advancing far enough to get themselves acquired. These will be decade-long projects. Participants in those fragmented industries need to decide whether the gains in growth and efficiency are worth the risk of being at least partially commoditized by a new, dominant transaction platform—and, if not, whether they can act in concert (as banks are attempting to do) in order to protect their autonomy.

2. ORGANIZATION AS MUCH AS TECHNOLOGY WILL DETERMINE THE RELATIVE ADVANTAGE OF BLOCKCHAINS. A central conflict over the next few years will be between permissioned blockchains curated by coalitions of intermediaries and the far more radical program to give end users direct access through open protocols. Oligopoly versus democracy, as some would have it. In many intermediary industries such as financial services, incumbents are rationally responding by adopting the technology among themselves. But it is a big and open question whether that will ultimately suffice. Open blockchains enjoy an advantage in scale: they have more blocks, more nodes, and more rigorous validation. By design, they can add participants less constrained by diminishing peripheral trust. But permissioned blockchains have an advantage in scalability relative to their target transaction network. They need fewer participants and can dispense with nonscalable features such as proof-of-work. So whether and when the status quo is disrupted—and by how much—depends less on the absolute pace of technical advance than on the relative pace at which private and public implementations advance. And that is largely a contest of political organization. Industry consortia need to work together when their members are otherwise competing. And open communities need to stick to a single script when individuals have diverse ideological commitments and are tempted to fork the codebase. The strategist needs to understand both, intimately, and be clear-headed about which camp holds the winning hand.

3. GOVERNMENT IS A WILD CARD. The current regulatory climate is surprisingly favorable. Bitcoin is legal in most jurisdictions, regulated as a commodity but not as a financial instrument. The primary focus of regulation is the top of the stack (exchanges, in particular) rather than the bottom (blockchains). Indeed, blockchains facilitate regulatory goals: they reduce counterparty risk, can comply with know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering rules, and can provide an efficient “backdoor” access to transactions. But of course the regulatory climate could change quite suddenly, especially in the face of security vulnerabilities. On top of that, governments themselves could drive transformative blockchain applications in identity, health care, and digital currency. They have the incentive and the critical mass. Many policymakers see this kind of technology as the catalyst for broader economic stimulus, job creation, and national competitive advantage. Some countries are more likely to think that way than others.

4. FINANCIAL SIGNALS ARE PROBLEMATIC. There are already murmurs in some boardrooms that the ROI on these technologies is not that impressive. Highfalutin rhetoric about embracing digital disruption notwithstanding, incumbents have little incentive to collaborate and invest to create a level playing field that merely lowers industry prices. Executives have to believe either that such innovation will open new markets or that it is a necessary response to a real disruptive threat. Otherwise, it is easy to imagine the majority quietly shelving the technology and the grand industry coalitions falling apart. A few “visionary” CEOs will ignore their bean counters. If the disrupters later succeed, those visionaries will become the heroes of business school case studies—and if not, the fools.

5. RADICAL UNCERTAINTY IS THE NORM. It only takes one really compelling and broad-based application, one killer app, to drive widespread adoption and pull through complementary infrastructure, products, and services. All we know is that it’s not bitcoin, the currency.

Conversely, some hacker could find an irreparable security flaw: not enough to deter enthusiasts, perhaps, but sufficient to spook the regulators. Or scalability could prove an insuperable problem.

Or a middle scenario: a few disparate applications might enjoy modest success without converging into a tidal wave comparable to the PC or the internet. Transformational ideas could die on the vine for lack of self-fulfilling momentum. Silicon Valley could have another bust or just move on to the next new thing.

The truth is that nobody knows.

As with any early-stage technology subject to network effects and strongly increasing returns, the business equilibrium is radically unstable. Strategy cannot be based on a “point estimate” of what the future will look like, whether derived from financial projections or a grand vision. Instead, strategy under conditions of uncertainty must focus on acuity, options, and experimentation.

1. ACUITY. Your organization needs to know its environment intimately: the technology, competitive moves, alliance politics, crazy startups, and shifts in public policy. Look out for discontinuities. Some open blockchain protocol could eclipse the closed efforts of an industry consortium; some government-sponsored initiative on the other side of the world could catalyze a killer app. Some breakthrough in encryption—or decryption—could transform security or scalability. Some development in another industry could wash over yours, the way whole industries became mere apps on the PC or the internet. Acuity cannot be delegated, because the correct framing of the threats and priorities is not yet apparent. Senior managers need to be part of a process of continuous learning.

2. OPTIONS. In strategy as in finance, the greater the uncertainty the greater the value of having options. Options are an investment whether they pan out or not; it is false economy to skimp or delay until the outcome is evident. So at the risk of redundancy, and even of supporting contradictory or competitive initiatives, invest broadly. Buy into a portfolio of alternative technologies. Join industry alliances and consortia: membership will give your organization early participation in whatever succeeds, the chance to learn, and an opportunity to shape the group’s priorities from the earliest stages.

3. EXPERIMENTATION. Apply “agile” principles to the development of small-scale token and blockchain applications. Experiments matter because they can point to a “strategy” and also because the very practice builds operational capability and confidence. MIT's David Clark famously articulated the mantra of the early internet community as “rough consensus and

So stay close to the coders, the entrepreneurs, and the policymakers. Keep your options open. Experiment. These are the watchwords for thinking outside the blocks. And they are better guides to strategy than the airy enthusiasm of evangelists or the myopia of bean counters.