Bank operating models continue to evolve in response to new regulations, digitization, a volatile economic and risk environment, external threats, and advances by nontraditional competitors. This evolution presents new types of operational risk (OR), and many banks are suffering large losses or embarrassing headlines from cyberbreaches, new varieties of fraud, third-party issues, and unreliable technology.

In response, many banks have increased their spending on OR management by more than 50% in the past five years. Yet boards and executive teams have begun to question the effectiveness of these investments. One bank executive noted, “We can invest an additional $10 to 20 million, but not really know if what we’re doing is more effective,” and then added, “We seem to default to rote, tick-the-box exercises that satisfy our regulators but aren’t risk based or aligned with business value. There has to be a better way to do this.”

To understand how banks are dealing with the increased strategic importance of operational risk, BCG benchmarked the performance of ten major banks globally. The results show that some banks have begun to crack the code. Besides becoming more effective at managing operational risk, they are achieving high performance without sharply elevating their OR spending.

Learning from Leaders

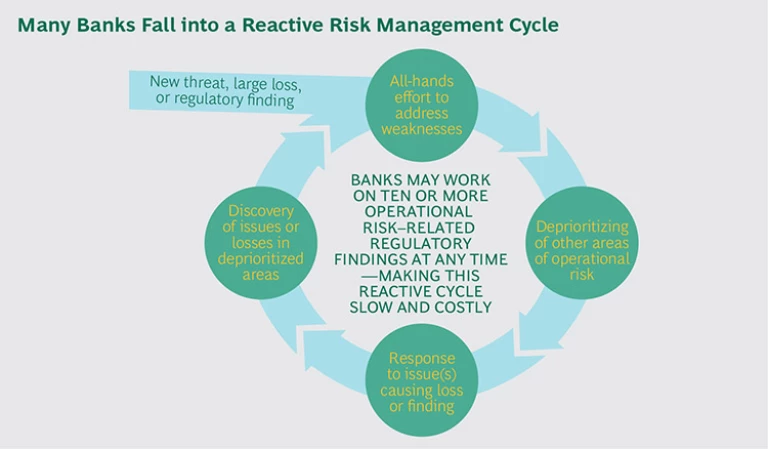

Over the course of several months, we conducted extensive interviews with executives and operational risk teams within the traditional second line of defense or oversight role, and within the operating businesses themselves. The results indicate that many banks find themselves in a reactive cycle in which discovery of a new threat, loss, or regulatory finding leads to an all-hands effort to address weaknesses—an effort that usually entails adopting a resource-intensive point-solution that draws people and attention away from other important or new operational risks. (See the exhibit.)

BCG’s benchmark also revealed a number of banks that have excelled in dealing with OR. Three institutions—one from Europe and two from North America—stood out for their ability to create and execute a more proactive, integrated, and sustainable approach to operational risk. While they had different strategies and risk profiles, our analysis found that these leading OR institutions do five things especially well.

They set clear objectives and maintain discipline around strategic priorities. Regulations require all large banks to have a risk appetite statement that includes operational risk, but often the goals stated for OR do not align with senior business leaders’ priorities. Often, the misalignment stems from translation issues. OR teams sometimes wade too deeply into technicalities, don’t understand how to “speak business,” or don’t discuss how risk issues relate to the bank’s overall goals. And some business leaders lack the knowledge base or fail to invest the time needed to keep up with evolving risk topics.

The leading OR institutions in our benchmark do things differently. They start by shaping consensus among senior leadership on the overall OR program in the context of the bank’s business objectives, and then they design the OR program accordingly. That process involves making thoughtful and explicit tradeoffs between risk reduction and operating cost. For example, one leading OR institution needed to make rapid changes to products and systems to gain competitive advantage and found that risks related to these changes were the primary driver of operational losses. That insight shaped the bank’s OR goals. The bank channeled spending toward mitigating risks caused by product and technology changes, and that focus gave the bank a clear way to prioritize spending and well-defined targets by which to gauge the success of the OR program.

Leading banks also avoid scaremongering. One board member complained that he was “tired of the cyberrisk executive sending alarmist articles without proposing any solutions or concrete goals.” Such tactics can gain attention and funding, but they usually backfire in the longer term. Phrasing risk topics in more-familiar business terms is often a more effective strategy. At one leading OR institution we studied, the OR team compares the process of managing risk to the more familiar process of buying insurance. That construct helps executives think about “how much coverage they want to buy and what it would cost.”

They manage mature risks cost effectively to free up and reallocate staffing and investment. Underperforming OR programs tend to budget backward, not forward. They typically revisit their strategy and budget only in the wake of large losses or when prompted by regulators, and they use additional investment to expand existing risk management processes past the point of diminishing returns, with “tick-box” exercises that grow more complex and cumbersome from year to year.

Top-performing OR programs are more flexible and strategic than other such programs. In mature areas of operational risk (that is, in areas with flat or declining risk and losses), the leading OR institutions in our benchmark act more aggressively. Instead of basing their staffing estimates on current levels (with some additional increase for remediation and hot spots), leaders regularly calibrate where their current and emerging operational risks are greatest and reallocate staff accordingly.

Further, whereas many banks leave proven but people-intensive OR processes alone, leading OR institutions use technology to provide a more efficient, repeatable solution. These leaders proactively create a cycle of reducing headcount in mature areas of OR through lean process redesign and automation to free up resources for newer, less mature areas. Those efforts significantly lower costs while continuing to support a consistent, high-quality control environment.

Our benchmark confirmed how difficult it can be for banks to withdraw resources from an established risk management area. For instance, one bank in our study continued, through inertia, to build out its business continuity program, increasing staff by more than 40% over a five-year period, even though the bank’s operational risk capital needs for business continuity had not grown and there had been no major business continuity incidents.

Adjusting or reducing risk resources takes boldness. But leading OR programs can afford to be bold because they have stronger risk assessment and risk capital processes. As noted, they examine and refresh their overall OR strategies at least every two years, and they use those insights to guide their investment decisions. One institution actively reallocates staff based on its operational risk capital requirements. As a result, that bank is far more successful in maintaining effective cost control over mature risks and is more nimble in scaling up its risk resources in new areas.

They create a strong predictive risk function to identify emerging risks. Besides managing mature risks more effectively, leading OR programs do a better job of surfacing and tracking emerging risks. Most have some type of “control tower”—a small group, usually housed within the second line of defense, that monitors the existing set of risks and spots new ones that might become serious.

Such groups help operationalize the risk-sensing function. They detect risks from various internal and external sources—by investigating anomalous loss incidents, researching external incidents within and outside financial services, and collaborating with industry and public sector groups. Individuals in one bank’s control tower group regularly meet with managers across banking disciplines, from business lines to call centers, looking for insights into what’s changing, where losses are emerging, and where other risks may be tapering off. They created a cyberrisk forum with peer banks to stay current on potential threats and mitigation efforts, and they use data from the Operational Risk Exchange (ORX) to monitor loss trends. That multifaceted approach allows the bank to keep pace with the evolving risk environment.

Effective control towers do more than track risks, however. They also establish flexible budgeting processes that allow them to redirect investment over the course of the year as risks that require stronger management emerge. In addition, they plan for scalability, assigning triggers for when they will make critical investments as the importance of a particular emerging risk increases. Should the risk level reach a stage at which it merits its own policies, procedures, and dedicated management team, the control tower can recommend the creation of a separate formal risk program.

By maintaining a more responsive budgeting and management process around emerging risks, the leading OR institutions in our benchmark are better able to respond to a dynamic risk environment, thereby improving overall risk and cost performance.

They articulate clear roles and responsibilities for each line of defense. Blurred roles and responsibilities between lines of defense hinder many OR programs, leading to redundancy in some cases and to gaps in others. In the absence of well-defined roles, many second line OR functions may be stretched to cover issues that the first line might manage, to the detriment of their core responsibilities. At one bank, business managers felt ill-equipped to deal with tracking OR issues, so they pushed the task to the second line. But because the second line team was understaffed and distracted by several remediations, it missed two important trending risks that ultimately cost the bank over $200 million.

Leading OR institutions spend time clarifying the roles for each line of defense and ensuring that each line has the skills needed to perform its duties. Role charters detail these assignments so that all stakeholders understand their exact responsibilities. This process helped one bank identify gaps in its approach to cyberrisk and revealed the need for improved training to help programming teams execute their cyberrisk responsibilities. Now the bank has an annual process to evaluate the roles and responsibilities of every line of defense, ensuring that each has the skills needed to succeed. The bank also created a rotation program that enables high-potential second line staffers to spend time in audit and first line operational risk roles to deepen their skill base and, ultimately, improve the quality of the second line.

To ensure effective oversight of all operational risk topics, leading institutions create small teams within the second line to oversee topics such as cyberrisk where the first line organization formerly had sole responsibility. The banks keep these teams small so they cannot take on any operational roles. By staffing the teams carefully, the institutions ensure that they have the expertise to provide a credible challenge to teams in the first line of defense (for example, by hiring former cyberrisk consultants to staff the second line cyberfunction). In stark contrast, many less effective banks manage certain critical risks exclusively within the first line.

In addition, to help support the operational risk needs of the business, some banks have created a dedicated risk unit within the first line—often called a “line 1.5”— to manage aspects of its operational risk, such as issues detected by the second line, by audit, or by the first line staff. These structures are most effective when they support specific first line needs (rather than duplicating the functions of the second line), such as cyberoperations or quality control.

They revise incentives to lock in the behavioral changes needed. Many regulators now require that risk management be part of senior leaders’ bonus calculations. Not all such programs have been effective, however—and in some cases, they have even created perverse incentives. One institution, for example, rewarded business leaders based on how many OR issues they resolved, only to find that those leaders self-identified many low-risk issues expressly to close them out.

Leading OR institutions try to find the right balance by mixing formal rewards based on risk outcomes with a strong set of informal incentives. They reward leaders who proactively address risks and punish those who hide them (by looking at such things as the percentage of issues that are self-declared and at losses that fall outside the formal list of top and emerging risks.) In one case, a leading OR institution demoted a rising star in a large business whose team had presided over an unusually large operational loss—an action that sent a clear message to other managers regarding the importance of risk management.

Building a Leading Operational Risk Program

Institutions that aspire to build a leading program must take a few crucial steps. The first is to create clarity around OR goals, showing how and where superior OR management will add value in line with the bank’s overall strategic direction. This should lead to a concrete statement or set of metrics defining success (phrased in business terms) that board and senior management support. For example, a bank focused on customer service might say, “To support an outstanding customer experience, our operational risk program’s goal is to prevent material customer-facing disruption or error.” Agreeing on those goals requires careful prioritization and, in some instances, difficult tradeoffs.

The second step is to address critical obstacles to achieving the bank’s OR goals. This may require a short-term ramp-up in resources to manage immediate priorities, so as not to divert other resources from moving the rest of the program forward. For example, one bank hired a team of contractors to improve a technology risk program to meet regulatory expectations. By focusing these temporary resources on a specific goal, the bank created goodwill with the regulators, tapped technical experts to build an effective program, and freed in-house OR teams to focus on other improvements.

The third step is to build a set of OR competencies (no more than three to five to start) that support specific elements of the bank’s business strategy. To help one bank achieve its goal of differentiating the quality of the customer experience, the bank’s OR leaders focused on controlling risks from frequent changes in products, processes, systems, and organizations, which they had identified as being the leading causes of service disruption for customers. The bank also sought to improve the reliability of its core consumer platforms to prevent further failures. By developing targeted sets of competencies capable of evolving in line with strategy, leading OR programs in our benchmark have gained and sustained traction, notched measurable successes, and built credibility.

Despite increased investment, many banks feel unsure about whether their OR programs are performing effectively in what has become a more complicated and volatile environment. With digitization, regulation, and globalization disrupting the business and operating landscape, banks can no longer afford to rely on static, check-box controls. Instead, as our benchmark shows, the most effective OR programs need to become as dynamic, targeted, and responsive as the banks’ own operating business lines, with a well-defined and well-aligned series of objectives, better resource allocation, superior risk detection and mitigation capabilities, clear roles, and revised performance incentives calibrated to sustain the desired behavioral changes. The banks that most effectively channel their OR efforts in these five areas will be in the strongest position to anticipate and protect against risks that threaten growth and profitability in both the short run and the long run.