The financial technology (fintech) phenomenon first started to evolve in the capital markets (CM) industry more than 40 years ago. Today, accelerated both by the electronification of trading in the 1990s and the subsequent thrust of the entire financial services industry toward digitization, fintechs—which we define as firms that use innovative technology at scale to either enable or compete with other financial institutions—have experienced exponential growth in the CM domain.

The most prominent CM fintechs have been strongly supported and engaged by the CM ecosystem, which includes players such as investment banks, custodians, exchanges, clearing-houses, and CM-focused information service providers. Such players have been, and will remain, best positioned to pick the most promising fintechs for potential collaboration.

Yet despite rapid growth, CM fintechs have been attracting less than their fair share of venture capital (VC) funding. This shortfall is partly due to the highly specialized and regulated nature of capital markets, which may hinder outside investors. Indeed, when fintechs are backed by incumbent banks, they attract greater funding and mature more quickly than when they are backed solely by VC firms. Incumbents that invest actively can shape business models and help fintechs evolve into collaborative suppliers rather than disruptors. Moreover, the funding that CM fintechs have received to date has been heavily focused on front-office initiatives within execution and pre-trade. Funding for post-trade activities has been much more modest, with investment concentrated in a select number of fintechs, resulting in the highest average ratio of funding per company.

Simply put, fintechs focus on creating new value propositions or improving existing ones. They help build capabilities that can enhance client relationships, reduce costs through automation and simplification, and facilitate regulatory compliance. They also enable disaggregation of the value chain as they become more embedded in the supply chain.

Nonetheless, in order for the fintech boom to realize its full potential, a number of barriers must be overcome in the way that fintechs relate to investment banks and the CM ecosystem as a whole. These hurdles exist in the areas of simplifying IT architecture, developing industry standards, improving collaboration among players, and mitigating the risks of working with vendors, among others. Moreover, inertia on the part of incumbents can have a dire consequence: the inability to compete with new entrants that use cutting-edge technologies to reverse banks’ traditional competitive advantage. Market structure changes brought on by technology, regulation, and shifting client needs make it critical for incumbent banks to take action now.

In addition, as banks begin to think of themselves more as data and technology companies, they need to start managing their IT stacks, and the data and analytics within them, as assets that can be commercialized. Banks can leverage the experience gained in such areas as execution algorithms, direct-market-access connectivity, and securities services, and explore opportunities for unconventional partnerships. In order to move forward efficiently and effectively, however, banks must fully grasp the history and scope of the fintech domain. In this report’s analysis of the rapidly evolving CM fintech landscape, we used the Fintech Control Tower proprietary database of Expand Research, a BCG subsidiary. The database covers more than 8,000 fintechs.

The Fintech Landscape

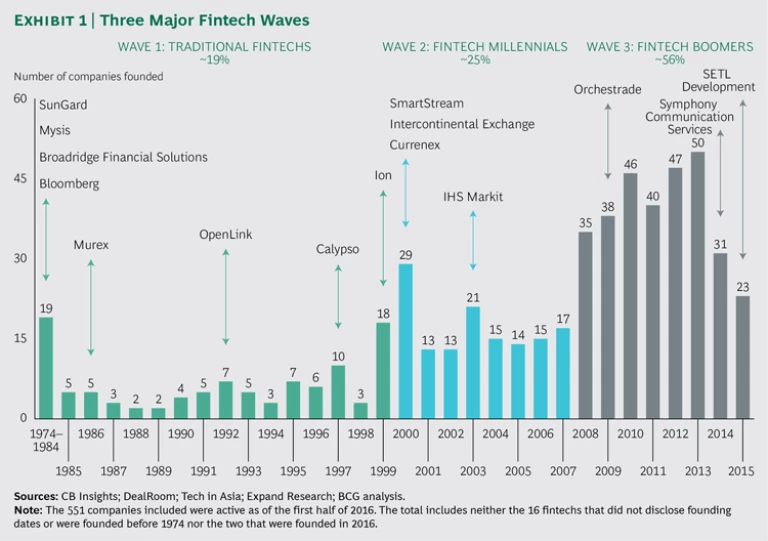

Since the establishment of Instinet as the first electronic communication network in 1969, and the creation of Nasdaq as the first electronic exchange in 1971, there have been three major fintech waves. (See Exhibit 1.) The first occurred mostly in the 1980s and 1990s and featured roughly 100 CM fintechs, predominantly enablers, that focused on market data, news distribution, risk management, and core processing. Most of these players are now embedded in sell-side and buy-side firms. Market electronification accelerated with the introduction of the Financial Information eXchange protocol in 1992, and by the late 1990s, electronic venues, such as Electronic Broking Services, had become the primary trading vehicles for interdealer foreign-exchange transactions.

The second wave took place from 2000 to 2007 and comprised just under 140 fintechs that focused more on e-trading. These players included business disrupters, such as high-frequency trading, and execution platforms, such as Currenex.

Starting in 2008, the post-crisis wave of about 310 fintechs evolved to mostly comprise enablers designed to fix the post-crisis challenges of falling revenues, high costs, complex legacy infrastructures, and fragmented liquidity and data. One such player was the buy-side-to-buy-side venue Luminex. Today, many of these firms are emerging startups with regulation built into their DNA. They use cutting-edge technologies, such as machine learning, which are often delivered as a service.

It is worth noting that the latest wave of digitization is being fueled by incumbent banks’ rapid digital transformations and is characterized by paradigm shifts in technology instigated by the proliferation of cloud hosting, artificial intelligence, peer-to-peer computing, and distributed ledger technologies. Regulation has been a key driver of the latest fintech explosion, as CM players have moved toward low-capital-intensive business models that require enhanced technologies.

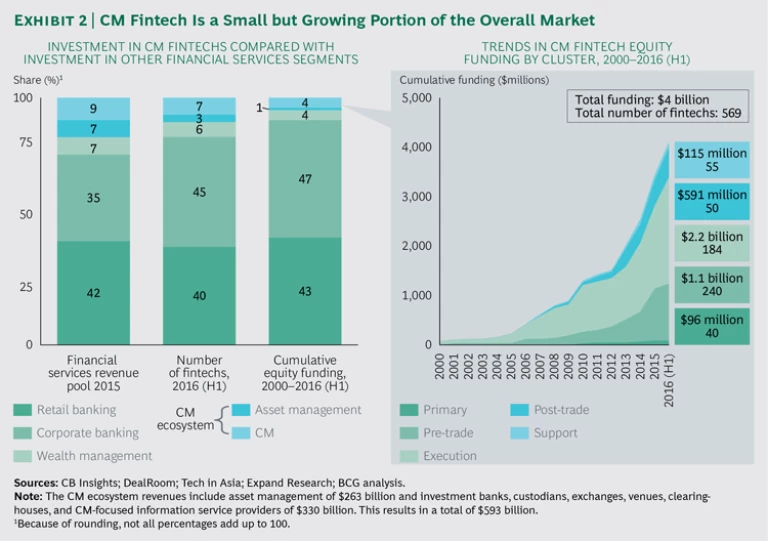

Capital Markets Fintechs Have Received Less Than Their Fair Share of Funding. Of the roughly 8,000 fintech startups that we track globally across all business lines, only 569 are active in the CM space. And of the roughly $96 billion in VC funding that has been raised since the turn of the century, only about $4 billion (or approximately 4%) has gone specifically to CM fintechs. (See Exhibit 2.) Thus, it is clear that the potential gains are much larger than those currently being realized. Indeed, the 2015 CM revenues of $330 billion (excluding those related to asset management) represent 9% of the total financial services revenue pool of $3.67 trillion. Therefore, the CM equity funding ratio, relative to the revenue pool share, is skewed at 1:2, with CM fintechs attracting less than half their fair share. If we use the broader definition of the CM ecosystem, which includes asset management, the ratio is even more pronounced, at 1:3.

The vast majority of fintech disruption in the banking industry is happening on the retail and corporate fronts, where technology provides a way for companies to serve large, diverse client bases while still reducing the cost of customer acquisition across a number of distribution channels. The prospect of mass adoption makes equity financing readily available, with numerous VC firms on the lookout for the “Uber moment” of finance. As a result, there is a large imbalance in the amount of VC investment going to retail and corporate banking versus the amount going to CM firms. The handful of CM-focused startups that do exist have not only generated fewer VC funding rounds than their retail- and corporate-focused peers, but they have also attracted significantly less funding per round: roughly $11 million in CM in 2016, compared with about $14 million in retail and corporate banking.

Such differences are partly attributable to the perception of a higher risk of failure in the CM industry, which is highly specialized, heavily regulated, and dominated by a few incumbent players. This reality discourages VC investors who are not industry specialists. In light of this, many CM players have taken up the dual role of investing strategically in new tech ventures as well as representing their traditional client bases.

An Attractive Investment Opportunity. Indeed, despite perceptions to the contrary, the overall CM ecosystem has thrived in recent years, generating a sizable revenue pool that is expected to markedly increase over the next five years. (See Global Capital Markets 2016: The Value Migration, BCG report, May 2016.) Given the size and growth of the industry, as well as the less crowded landscape, the CM fintech space is an attractive market for both investors and entrepreneurs.

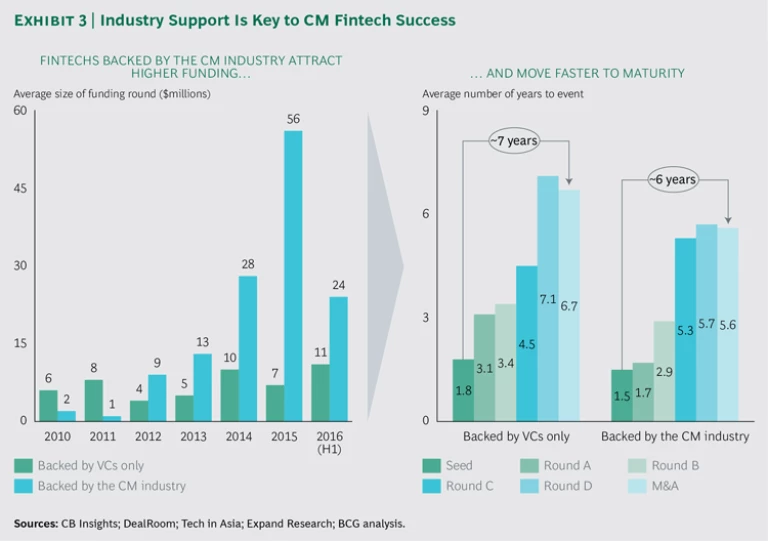

In addition, as we have seen, evidence shows that fintechs supported by banks or other strategic players, such as exchanges, tend to reach maturity faster and become more successful than those that are not backed by such players. (See Exhibit 3.) They also attract much greater funding, because VCs tend to follow strategic players in their investment allocations. The presence of such investors in fintechs signals that they are high-quality companies with credible business models and good prospects. On average, industry-backed fintechs reach the exit stage in six years, compared with seven years for firms backed only by VCs. Also, the average funding for industry-backed fintechs in the first half of 2016 was $24 million, compared with less than $11 million for those backed only by VCs.

Investment banks, however, have been facing revenue headwinds that are far more powerful than those faced by other players in the CM ecosystem. Indeed, information service providers are growing strongly and commanding price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples as high as 30 (compared with an average of 10 for investment banks). Banks have also been constrained in redistributing cash to shareholders because of recapitalization and deleveraging. Equity investments, therefore, provide avenues to reinvest retained earnings in projects with high returns on investment, helping to deliver long-term value to shareholders. Fintechs can help investment banks across the value chain by monetizing existing assets, such as data and algorithms, as well as by mutualizing industry costs. So-called know your customer (KYC) tasks, market data, client-reference data, and trade surveillance currently amount to $4.4 billion in annual IT and operations costs. And the opportunity will be even larger where efficiency is a primary goal, such as in the automation of trade processing. (See “Blockchain-Based Solutions.”)

BLOCKCHAIN-BASED SOLUTIONS

The main promise of blockchain technology in capital markets lies in the full automation of trade processing across asset classes. The greatest expected impact is on products such as syndicated loans, foreign exchange for currencies not covered by continuous linked settlement, and over-the-counter derivatives, whose back-office processes remain largely manual.

Blockchain-based solutions are currently being developed through two approaches: industry collaborations that involve multiple players, such as the Hyperledger Project, and efforts led by individual players (SETL, NASDAQ OMX Group with Chain, UBS with Clearmatics Technologies, and the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation). However, although prototypes exist, there is still minimal traction within the industry because of the relative immaturity of the technology and the fact that solutions based on private blockchain implementations are the only acceptable alternatives to bitcoin-like public chains for financial institutions.

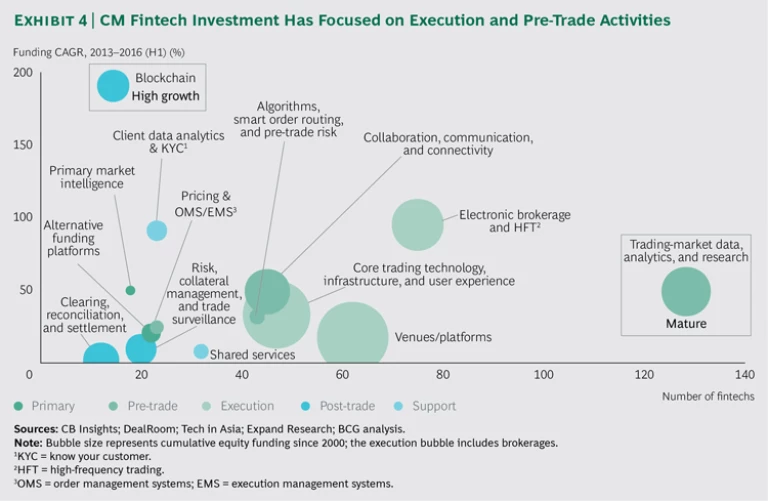

Of all the tech clusters, blockchain-based fintechs have experienced by far the highest compound annual growth rate over the past three years. Yet disclosed funding for such projects is still significantly behind other areas of innovation, such as data and analytics (a ratio of 1:4). Cross-industry settlement of billions of daily trades among globally dispersed counterparties, although theoretically feasible by using blockchains, represents one of the toughest use cases for a technology still in its infancy. Automation of more simple processes, such as recording client data on decentralized ledgers for KYC and for anti-money-laundering purposes, is likely to emerge first.

Execution and Pre-Trade Take Center Stage. Investors have been choosing fintechs that focus on enabling execution and pre-trade activities (with funding of about $2.2 billion and $1.1 billion, respectively), at a combined ratio of about 6:1 relative to post-trade activities. (See Exhibit 4.) Moreover, post-trade and support remain the least mature segments of the value chain, with early rounds up to series B representing 82% and 64%, respectively, of the total funding they have received since 2000.

For investment banks, this dynamic partly reflects an effort to revive the age of revenue growth, notably by increasing the share of client wallet. Although there are areas in which banks could create new products and increase trading volumes, the pursuit of market share in a stagnant environment is a zero-sum game for the industry as a whole, because competitors can improve their relative positions only by capitalizing on market share dislocations.

Also in play are reactive strategies to maintain positioning in a market with increasing electronification. With front-office compensation representing roughly 40% of total costs, banks recognize the benefits of moving toward more cost-efficient service models with lower front-office headcounts. Most important, banks may be finding it easier to apply front-office technology, which can be deployed one bank at a time, rather than back-office initiatives, which could require significant industry collaboration to fully realize any benefits. Moreover, although explicit post-trade costs represent 15% to 20% of the total cost base, the implicit costs arising from cash flow inefficiencies, such as excess collateral for clearing, can weigh down capital resources.

Ultimately, data and analytics underlie the entire value chain, and investment banks have started to recognize data as a strategic asset that offers differentiation opportunities. (See “The Focus Is on Data and Research.”)

THE FOCUS IS ON DATA AND RESEARCH

The data and analytics niche is one of the largest for CM fintechs: approximately 150 companies are active within the space, and they have received $670 million in funding. Another 950 companies, with $11 billion in funding, offer solutions to CM players as well as to the wider financial services market. Such proliferation of fintech firms is not surprising, considering that the efficient processing and exchange of information underpins the CM industry. Moreover, the explosion of available data means that the opportunity for harnessing it is both urgent and critical.

Historically, broker-dealers were the principal accumulators and gatekeepers of data, deriving power from their market-making role in the order flow. But poor data governance and too many silos have led to significant underutilization and undervaluation of this asset.

Today, the financial services industry treats data management as a primary function. And while the role of the chief data officer has become relatively established, the position will continue to evolve as data begins to be monetized. This increase in importance has been enabled partly by the regulatory push for transparency and standardization in the markets, as well as by recent technological advancements in aggregating and analyzing both structured and unstructured data.

Despite this progress, however, issues with data management are far from resolved. Big data solutions are sometimes deployed on top of existing data silos to meet short-term goals, with few improvements in the underlying core data architecture. To avoid amassing an ever greater technological burden within the organization, therefore, deployment must be accompanied by efforts to improve data governance standards.

The value migration happening today has been aided by a reduction of information asymmetry, as exchanges, information service providers, and the larger buy-side players hold information that is comparable to that of broker-dealers. Moreover, the regulatory drive for unbundling is causing providers to price research on a standalone basis and to find new ways of monetization. The intellectual property within research can be used to launch indices and systematic strategies, in line with the move of investors toward low-cost index funds and smart beta investing.

When it comes to distribution, some fintechs, such as the research aggregator Visible Alpha, can enable the delivery of research in new ways. This includes access to the underlying analytical models, semantic search, and sentiment scoring capabilities, so that research consumers can mine the large daily output in unique ways. Also, licensing agreements can provide revenue sharing opportunities from the rise of alternative data. The Chicago Board Options Exchange, for example, has partnered with Social Market Analytics to launch dynamic indices that track stocks with high sentiment scores and facilitate options trading based on social media.

The Fintech Value Proposition

Banks are constantly in search of measures that can help them restore ROE. In addition to monetizing existing assets and mutualizing costs, fintechs can come to their aid by building capabilities to improve existing client relationships and experiences, streamlining front-to-back costs, and optimizing regulatory compliance.

Improving Client Relationships. Fintechs can help prioritize profitable clients and optimize pricing and sales strategies. For example, transaction cost analysis can help establish a complete internal view of client profitability through rigorous analytics, allowing banks to raise their game on pricing, increase hit ratios, and capture client flow. Such initiatives can shield banks from increased competition, as client flow is expected to become more price-sensitive with the advent of the second Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFid II) and its best-execution requirements covering nonequity asset classes. In addition, banks can provide more coverage and high-touch resources to clients that have a more profitable flow.

A second category of front-office fintechs is focusing on enabling banks to increase retention by improving the client experience and helping banks embed themselves into their clients’ workflow. Indeed, until recently, most front-office applications were built in-house, available only on specific platforms, and siloed under a thin layer of integration at the level of the user experience. Today, driven by the adoption of a suite of HTML5 technologies, this situation is changing as the industry moves toward a more flexible user experience model. Fintechs can now enable banks to create a smooth and unified client experience that tracks behavior across different platforms. Moreover, new fintech offerings such as multi-issuer structured product platforms allow banks to match products with investors’ risk preferences, thus shifting product governance to more client-driven, self-service solutions that avoid inappropriate selling.

The reality is that many investment banks lag behind organizations in other industries when it comes to tracking customer satisfaction, at a time when customer expectations have increased substantially. Banks thus have an immense opportunity to leverage predictive-modeling solutions that blend financial-market and client transaction data to understand and anticipate client needs. Use cases vary from establishing client profiles and predicting demand for certain products to forecasting the propensity to issue equity or debt or to perform block trades.

Partnerships with fintechs can also reduce the time to market for proprietary products and services and increase revenue. For example, Goldman Sachs collaborated with Motif Capital to issue structured products that express the unique thematic views of clients.

Streamlining Costs. Most fintech enablers in the CM ecosystem have a lower-cost component in their value proposition and can thus provide investment banks with an alternative route to additional efficiency gains. Consider the modern trading desk, for example, which is evolving to adopt a unified communication approach that merges channels, such as voice and electronic (including digitizing voice trading through speech recognition). Services that enable trading from any location, while leveraging cloud-computing services, could become ubiquitous in the future. Such software could eliminate large portions of legacy systems and costly private-communication lines, as well as improve overall asset productivity. By moving to internet-based cloud-computing services, investment banks can rent computing power and hardware in a way that efficiently meets fluctuating demand.

In addition, mutualizing costs in post-trade and support is a particularly attractive opportunity, the benefits of which have yet to be fully realized. Current utility players are still nascent, and adoption is slow because the market remains fragmented.

Meanwhile, process automation is expected to maintain momentum across both front- and back-office activities as machines continue to replace human workers. Some of the most promising areas are intelligent processing, which can be found in functions as varied as robotics and machine learning systems, and the application of distributed ledger technology for settlement, confirmation, and reconciliations. Other potential areas to realize cost efficiencies include connectivity and order management systems in fixed-income and trader communications.

In many of the above cases, the potential for cost reduction on the respective functions can be significant (greater than 50%). However, the transformation should start from the ground up, with the infrastructure layer, to avoid leaving fundamental IT architecture problems unresolved.

Furthermore, to become credible as a viable substitute, fintechs must offer high standards of service and reliability. To be sure, a major challenge in adopting innovative solutions today is building trust. The potential for regulatory accreditation can quickly raise fintech credibility.

Overall, up to 75% of sell-side IT costs are nondifferentiating, according to Expand Research. A large proportion could be externalized to fintechs over the next 15 years, leaving the remaining 25% to be built and managed internally as a competitive asset—such as by developing systems that provide pricing sophistication, client analytics, and execution.

Optimizing Regulatory Compliance. Regulations have been a huge burden for investment banks since the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In investment-banking technology functions alone, around $3 billion is spent annually on regulatory and compliance IT, which includes only officially reported regulatory projects. So-called regtech firms, which have received about $200 million in funding, have stepped up to help banks navigate the evolving regulatory maze. Currently, there are more than 400 sources of regulatory information, with many regulatory tasks (such as KYC and trade surveillance) requiring extensive manual efforts. Regtech companies, deploying technologies such as natural-language processing and machine learning, promise to automate these processes while reducing duplications caused by regulatory requirements that overlap across jurisdictions. In addition, behavioral technologies, such as Behavox, can analyze employee actions and provide risk warnings for possible noncompliance, helping banks proactively deal with any conduct issues that could cause incidents.

Implicit in the efficient use of any regtech tool is maintaining a certain level of data standards. Regulatory harmonization and convergence require international coordination between the private sector and the official sector. The regulatory goal of developing a more robust financial system must involve developing and adopting data standards, such as the Financial Industry Business Ontology common language, and finding ways to nurture the regtech ecosystem.

Four Factors Are Critical to Getting the Most Out of Fintechs

The value that can be delivered by CM fintechs is often diluted by certain industry barriers that need to be understood and overcome. These barriers exist in areas such as simplifying IT architecture, developing industry standards, improving collaboration among industry players, and mitigating the risks of working with vendors.

Simplifying IT Architecture. Over a period of years, many banks have been adding IT infrastructure without consolidation, resulting in excessive complexity. That complexity, in turn, has required banks to deploy middleware to provide interfaces among their fragmented applications. In addition, dealing with a large number of vendors places significant strain on internal resources. Ultimately, investment banks need to avoid creating additional application layers and work to become more agile in order to integrate fintechs and transform the IT architecture uninhibited by legacy issues. The agile method delivers iterative, minimum viable states that continue to communicate with the existing infrastructure and allows for gradual migration to the new platform. Agile involves rapid prototyping to identify use cases and develop solutions that help a company adapt its IT operating model more quickly.

Developing Industry Standards. Although CM players can play a significant role in developing common assets, regulators can act as a catalyst for technological innovation by promoting standardized solutions. For instance, the European Securities and Markets Authority decided to use International Securities Identification Numbers as identifiers for derivatives under MiFID II in order to expedite implementation. The industry is still grappling, however, with a common standardized approach for describing all facets of the CM universe, such as reference data for distributed ledger technology, given the complexity of the financial instruments, entities, and processes involved.

Improving Collaboration Among Industry Players. Governance frameworks within industry-owned fintechs can foster better collaboration among industry players, increase adoption rates, and promote goodwill on the part of incumbents because they have a stake in ensuring their fintech partners’ success. In addition, initiatives such as Project Neptune, launched by a group of banks and investors to facilitate the exchange of fixed-income inventory information among participants, demonstrate the benefits that accrue to both the sell side and the buy side as a result of unifying their efforts.

Indeed, the current lack of interoperability and open innovation among fintech and CM players hinders new business and sourcing models. The adoption of open innovation principles can drive cocreation across firms by combining enterprise assets in new ways. Some of these assets could be monetized by individual firms. Application programming interfaces (APIs), for example, have become a prominent feature of the digital economy and constitute a core capability of technology leaders such as Uber, Twitter, Google, and Facebook. Moreover, third parties can develop applications that leverage enterprise assets though APIs, thus connecting firms, developers, and end users. CME Group, for instance, has partnered with Dwolla to make real-time margin payments on behalf of CME’s customers.

Mitigating the Risks of Working with Vendors. The advent of multiple startup firms supplying solutions to the market has led to the perception of an increase in risks when working with vendors. Reducing these risks will be critical for the industry to drive innovation. At the same time, in light of regulatory capital constraints, the appetite for operational risk has diminished.

For fintechs, many of which have yet to attain the necessary maturity to displace established practices, knowing how to build solutions that both minimize integration costs and enable the firms to work alongside other industry vendors in a seamless manner is crucial. Fintech clients will need to analyze and mitigate both contractual risks and operational risks, such as reliability and security. To help in these areas, some fintech offerings have emerged to provide so-called know-your-third-party services that simplify vendor due diligence.

Taking an Engagement Approach

Incumbent banks need to find the optimal engagement mix for interaction with the fintech community and actively select individual companies to acquire, invest in, or partner with. A recent BCG report described five potential innovation models. (See Global Capital Markets 2015: Adapting to Digital Advances, BCG report, May 2015.) The models are as follows:

- Business incubation and acceleration can provide support for, and cooperation with, startup companies in the early stages of development.

- Venturing allows banks to make equity investments in order to assess and take advantage of new growth opportunities.

- Strategic partnerships allow banks to explore joint ventures that drive incremental revenue and extend market potential.

- Mergers and acquisitions can act as fast-to-market solutions when investment banks acquire developed companies.

- Internal R&D has a significantly longer lead time and a considerably higher total cost of ownership, but it allows banks to maintain full control.

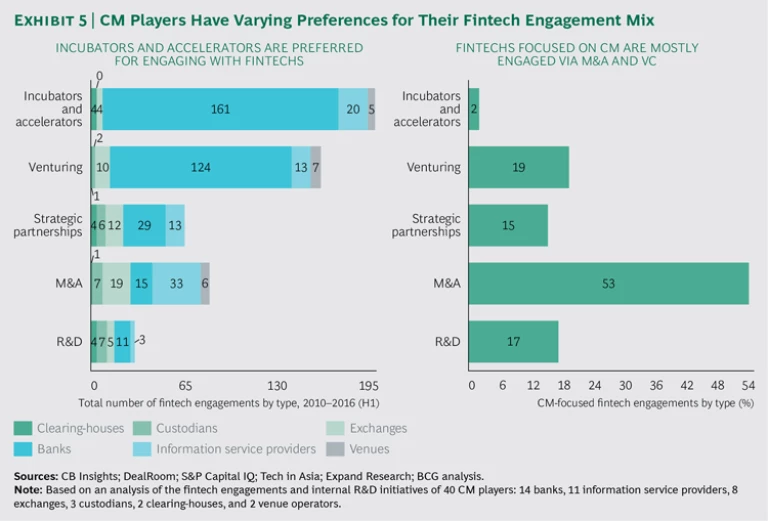

Our analysis of fintech engagement shows that incumbents’ preferences for the mix they choose varies according to the nature of their strategic growth plans (organic versus inorganic), their degree of innovation momentum, and their digital maturity. (See Exhibit 5.)

CM fintechs are mostly engaged through M&A and VC funding rather than through incubators or accelerators. This may be owing to the sophistication and high value of their intellectual property (IP), making them attractive acquisition targets. Challenging market conditions, including regulatory and cost constraints, have also meant that many CM players have preferred inorganic growth, taking advantage of consolidation opportunities and external innovation channels rather than internal development.

Information service providers have the most aggressive inorganic strategy, using mostly M&A to acquire fintech assets. Such providers also use strategic partnerships to extend their offerings. Exchanges and venue operators are the second most active in M&A, as they diversify into multiasset trading and nontransaction businesses. These players have been expanding into software segments that command loftier P/E multiples owing to higher expected growth. Favorable revenue prospects have also spurred these players to become active in internal R&D with new product launches and services.

Some banks have shown a balanced approach that includes the use of incubator and accelerator programs. These programs can afford such banks the first pick of promising businesses, the opportunity to cost-effectively outsource experimental R&D, and the ability to discover budding tech talent. Internal innovation labs, meanwhile, can help attract IT expertise. Moreover, investment banks have been registering patents to protect and monetize the IP they have been developing internally. For example, Goldman Sachs has filed patents both for a virtual settlement currency called SETLcoin and for swap futures contracts to secure recurring revenues from third parties. Regulators and central banks have launched their own accelerators with the potential to help fintech companies achieve authorization.

An Urgent Need for Action

Though the overall CM ecosystem has been thriving in recent years, the industry is facing a perfect storm of multiyear revenue declines on the sell side, an exodus of technical talent (partly toward fintechs) that requires banks to look outside their own organizations for resources, an expanding supply of fintechs brought on by the growing need to replace legacy IT architecture across the industry, and a wealth of maturing technologies (such as cloud, machine learning, and big data) that are ready to be applied to the CM industry. Banks must take action now both to protect their own interests and to boost the CM fintech ecosystem as a whole. These actions include:

- Focusing on standardization

- Opening the banking framework to reduce integration costs

- Improving strategic principal-investment capabilities to overcome the lack of VC funding

Banks also need to manage their technology stacks as investors do and quantify the value of their portfolios. For example, investment banks can identify potential ventures by leveraging their current IT assets, much the way Goldman Sachs has done by forming a joint venture with Synchronoss to begin monetizing its IP in mobile communication technologies.

Overall, the shifting competitive landscape has heightened the urgency for CM players to proactively explore fintech adoption. Nonbank players have already broken into traditional fortresses of investment banking, such as market provisioning. Capability gaps between nonbanks and banks have been decreasing, while investors have been growing impatient in the face of chronic underperformance. A wait-and-see approach is no longer viable. Banks that defer their options will lose significant value by not participating in the innovation process. They face the risk of disintermediation by competitors.

Ultimately, fintechs are introducing new paradigms that CM players can exploit to their advantage. (See the Appendix.) Proliferation in innovation means that the landscape is complex and difficult to navigate. By establishing labs to focus on early-stage, novel technologies that are core to their principal activities, and by systematically pursuing adjacencies that have synergies with their existing portfolios, investment banks can position their businesses for a bright digital future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their BCG colleagues, as well as Emily Chapman and Esther Gross of Expand Research, for their valuable input and insights.

The authors would also like to thank Philip Crawford for his contributions in writing this report, and Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Lilith Fondulas, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their assistance in its editing, design, and production.