Given the negative headlines that dominated news coverage about Africa in 2015, the casual observer might conclude that the outlook for business there is gloomy. But nothing could be further from the truth. If projections hold, Africa will have over 1.1 billion consumers by 2020—more than the populations of Europe and North America combined. And incomes are growing. In 2020, Africa will have twice as many affluent consumers as the UK. What’s more, our research shows that African consumers are very optimistic and eager to spend. A wide range of products and services have already found enthusiastic buyers. And certain products—like mobile phones—are a greater priority than food in some regions.

Among the highlights from our 2015 survey: Rural areas and Ethiopia are two emerging markets with growing potential; we explore the opportunities and challenges of each. And 75% of African consumers with Internet access are online every day—most using mobile phones; as a result, the growing market for mobile financial services could explode, especially given that consumers lack access to traditional banking services. We look at what it will take to capture these opportunities.

For multinational companies (MNCs) hoping to capitalize on the continent’s growing consumer market, one of the biggest challenges is finding answers to the following critical questions:

- What income levels drive consumption?

- Where is demand growth coming from?

- What products and brands command a premium?

- Where do shoppers buy specific items, and what is the status of e-commerce?

- How do consumer preferences and behaviors differ in different countries?

- Which emerging markets bear watching?

These are exactly the questions we’ll be answering in this year’s African Consumer Sentiment report—the go-to guide for companies seeking an inside track—and in future installments of the series. In 2015, The Boston Consulting Group and BCG’s Center for Customer Insight polled 11,127 consumers across 11 African countries. The consumers we interviewed represent a broad range of ages, incomes, education levels, and household types. Besides exploring the attitudes, budgeting, and spending behaviors of Africans, we looked at where consumers shop and tracked the effect of income levels on the purchase of specific products.

The result is a detailed, quantitative database that supports the theory of emerging consumer classes—not one, but many—across the continent. Africa’s countries, markets, and consumers have varying tastes, preferences, and behaviors. Understanding these differences is critical when trying to make inroads. For instance, the market for washing machines in Kenya is limited because of a broad skepticism that machine-washed clothes are as clean as hand-washed clothes. Insights such as these can help guide companies as they develop strategies for reaching and engaging Africa’s diverse and growing consumer base. We’ve divided our findings into four sections:

- “Consumer Pulse Check”: An overview of the survey findings on buying behaviors, brands, and purchase influencers

- “The Connected African Consumer”: Mobile Internet access, new business opportunities, and the growing market for mobile financial services

- “Market Watch”: The Market Attractiveness index and a deep dive into the emerging markets of rural Africa and of Ethiopia

- “Channel Insights”: Where Africans are shopping for specific products, and how to penetrate traditional trade outlets

Except for the discussion of emerging rural markets, the data in this report focuses on urban consumers.

Consumer Pulse Check

The consumers we surveyed in 2015 represent 11 African nations: Algeria, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa. We excluded consumers younger than 18 and older than 75, as well as those with no stated income and those who said they rarely or never made purchasing decisions for themselves or for their households. Most surveys were conducted face-to-face in the respondents’ homes, but we also spoke to some consumers in offices and shopping malls. (See the sidebar, “Survey Methodology.”)

Survey Methodology

BCG’s 2015 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey polled 11,127 consumers in February and March 2015 across 11 of the continent’s largest countries: Algeria, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa. Of the consumers we polled, 8,977 lived in urban areas.

The survey was a follow-up to BCG’s 2013 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey but added three countries—Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, and Ethiopia. The 2015 survey also asked some new questions; other questions were rewritten and don’t allow for longitudinal comparisons.

The survey population was designed to align as closely as possible with the general populations of Africa in terms of gender, income, and age. The data we collected from participants included age (participants were between the ages of 18 and 75), gender, income, ethnicity, employment status, marital status, education level, rural or urban residency, self-perceived economic class (elite, upper class, upper-middle class, middle class, lower-middle class, or lower class), household composition, employment status of other household members, whether the participant received financial support from or provided financial support to others, and shopping role (“I always or sometimes make purchasing decisions for my family or household”).

For individual countries, results are statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. We excluded consumers who were under 18 or over 75; those who rarely or never made purchasing decisions for their household; and those with no or undisclosed income. Most surveys were conducted in respondents’ homes, but we also spoke to some consumers in offices and shopping malls. With minor exceptions for cultural or practical reasons, the survey was conducted in the same manner in each country to control for survey results and allow for the highest confidence in cross-country comparisons. We selected rural and urban regions randomly from a sample set, and survey administrators chose sampling locations randomly within each region.

The survey data was not weighted to match the target population. To compare 2013 and 2015 data, we used survey responses only from urban consumers. Where responses within the 2015 data were meaningfully different, we compared rural responses with urban responses.

Key Survey Findings

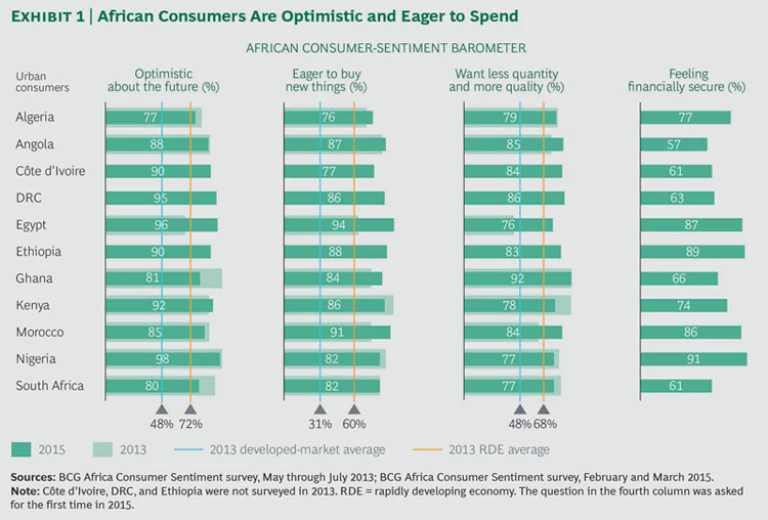

Our survey showed that 88% of African consumers are optimistic about the future. This bodes well for the continent, because optimistic consumers are more inclined to buy, which helps drive an economy forward. In the major consumer markets of Egypt, Kenya, and Nigeria, optimism is above 90%. The biggest change is in Egypt, where consumers have recovered their optimism and eagerness to spend, following a return to some political stability.

The overall optimism of African consumers is reflected in their eagerness to buy new things and the high levels of happiness they derive from their purchases. (See Exhibit 1.) Of our survey respondents, 85% agreed with the statement “It seems like every year there are more things I want to buy”—up from 75% in 2013. In Africa, buying and product ownership are closely associated with status and a sense of well-being. Particularly in Egypt and Morocco, consumers are buying more “luxury” items such as health and beauty products, appliances, electronics, vehicles, and clothing. This may be because people there have among the highest levels of financial security (more than 85%), which often determines whether consumers will spend more. By contrast, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, and South Africa reported the lowest levels of financial security. Consequently, people in those countries are buying fewer luxury items.

The proportion of respondents who said, “Even when my financial situation is bad, I’ll spend a little extra money to treat myself” varied considerably across the countries we surveyed (from 15% to 82%) but was still significantly higher, on average, than in developed markets and other emerging economies.

Africans are also discerning consumers, making well-informed purchasing decisions and willing to pay more for quality—especially for nongrocery items. The percentage of survey respondents who agreed with the statement “I buy less in quantity but pay more for quality” was higher in 2015 than in 2013 (82% versus 73%).

Brands and Other Purchase Influencers

Africans continue to highly value brands—some more than others—and social approval of a brand is an increasingly strong influence on purchasing decisions. Despite this finding, our survey showed that generational differences have grown. Compared with 2013, a larger number of respondents agreed with the statement “All things being equal, I don’t want my mother’s or my father’s brands.” But brands are becoming less important to the African consumer’s overall sense of identity. The share of respondents who agreed with the statement “Brands say something about who I am” dropped significantly from 67% to 56%.

Although leading brands vary widely across product categories, global brands are preferred. Nokia and Samsung are Africa’s favorite mobile electronic brands by a large margin. Brands are less influential in clothing, accessories, and shoes—many consumers can’t name a favorite brand—but Adidas is the relative leader in these categories. For example, 17% of survey respondents in Algeria favored Adidas for clothing and accessories, while 12% favored Nike—the second-most-preferred brand. In Angola, 14% of respondents preferred Adidas footwear, while 6% preferred All-Star, the second-most-preferred brand. Africans favor Japanese and German automobiles, although French brands are more popular in French-speaking countries. Toyota is the top choice overall. Fast-food preferences are extremely varied within and among countries, and local brands are usually preferred.

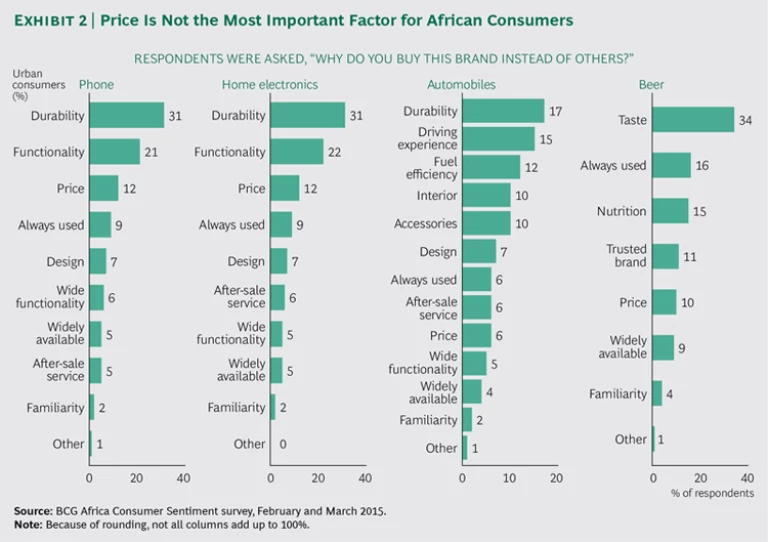

Interestingly, price is typically not the most important factor when African consumers decide what to buy. (See Exhibit 2.) Durability and functionality are primary considerations when they buy home electronics, while taste is the most important factor when buying beer. When entering African markets, companies should focus on hitting the right price points without sacrificing quality.

Brand longevity is less of a concern in Africa than it used to be. Today’s African consumers are more open to new brands—a development that bodes well for new products targeting the African market.

The purchasing decisions of African consumers are most influenced by spouses, partners, friends, and family across most markets. Although younger adults are more likely to be influenced by friends, older adults are more likely to be influenced by spouses or partners. In Morocco, 59% of adults aged 35 to 44 said that their purchases are influenced by spouses and partners, while just 31% of adults aged 25 to 34 agreed. In South Africa, just 13% of adults aged 35 to 44 said that their purchases are influenced by friends, while 33% of 18- to 24-year-olds agreed. Close to 40% of consumers in Ghana, Morocco, and Nigeria see friends as a strong source of influence—especially younger adults aged 18 to 24.

Television is by far the most influential advertising channel in Africa—much more so than radio, newspaper ads, the Internet and social media, and other channels. That said, companies shouldn’t completely ignore the Internet or social media marketing—areas of significant growth in some countries. Our research showed that Egyptian consumers are also strongly influenced by newspaper ads and billboards, Ghanaian consumers by radio ads, and Nigerian consumers by online advertising. Those differences show the need for a country-specific marketing approach.

The Connected African Consumer

The Internet is sweeping across Africa, as it is in the rest of the world, and connectivity is rising. Internet access is growing rapidly—up 8% since 2013 among our survey respondents. At the time of our 2015 survey, 63% of consumers across the continent had online access, but connectivity reached 83% in some countries. Fully 75% of consumers with Internet access were online every day.

New Business Opportunities

Mobile phones are driving this surge in connectivity. (See Exhibit 3.) Of our survey respondents, 43% access the Internet with their smartphones, and mobile usage is growing compared with desktops, laptops, and tablets. This growth of online access and the mobile Internet is creating new business opportunities in areas such as e-commerce, online advertising, and especially mobile financial services. But connectivity in Africa may pose some challenges. Power outages leading to intermittent connection issues and slower connection speeds overall will likely present obstacles. To succeed, companies will have to innovate and adapt to those conditions as well as to the specific needs of African consumers.

In 2012, for instance, the Africa Internet Group launched Jumia—Africa’s version of Amazon.com—in Nigeria and designed it to fit local needs. As one of the founders explains, “We saw a big opportunity. The reason Africa is not more developed is due not to a lack of demand but to a lack of supply.” The e-tailer sells a wide range of products and offers a mobile purchasing application. To ensure success in Nigeria, Jumia offers a cash-on-delivery option to build trust, and keeps customer-service and delivery functions in-house for better quality control, rather than outsourcing them. Jumia also forms partnerships with telecom companies, tapping into their large subscriber bases and giving their customers access to the Jumia website. Today, Jumia is among the top five online-shopping websites in five African countries—Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, and Nigeria.

Also capitalizing on Africa’s surge in connectivity is the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX), launched in 2008 to offer a secure, transparent, and trustworthy system for commodity trading. Before ECX, transactions in the country’s agricultural markets were high cost and high risk. To avoid being cheated or not getting paid, commodity buyers and sellers tended to trade only with people they knew. Only one-third of Ethiopia’s agricultural output reached the market. ECX provides a secure and reliable system for handling, grading, and storing commodities. The system matches buyers and sellers, offers risk-free payment, and provides a delivery system for settled transactions.

Information and communication technologies empower ECX buyers and sellers, including small farmers, to access markets more efficiently and profitably. For instance, the exchange offers text-messaging and call-in services in four local languages. Anyone in an area of the country where a mobile-phone network exists can access market prices, commodity-related news headlines, weather forecasts, and other relevant information. Currently, the messaging service has 800,000 subscribers and the call-in service receives 1.5 million calls per month.

Mobile Financial Services

Africa’s growing connectivity is also giving rise to a new market with enormous potential: mobile financial services. Today, more than 50% of all Africans over the age of 15 own a mobile phone. For most of these consumers, mobile banking will be their first experience with financial services. By 2019, an estimated 250 million “unbanked” Africans will have mobile phones and a monthly income of at least $500—generating a projected $1.5 billion in revenues from mobile financial services. Given the high cost to serve and low margins of traditional bank accounts in Africa, financial services providers haven’t made the continent a priority. As a result, 75% of Africans don’t have a bank. Mobile phones make up for the absence of a banking infrastructure. Although Africans use their phones to prepay utilities, purchase small items, and make debit-card transactions, they use them mostly to transfer money. Many urban workers send a portion of their earnings to their families.

A major opportunity exists to expand the range and types of financial services offered through mobile phones, providing new ways for consumers to save, borrow, invest, and transact business. Microloans, mortgages, mobile music, e-commerce, safer forms of cash management for businesses—all are ways that the mobile platform could be used to generate new revenues. The key will be for banks and phone companies to work together to realize this market’s potential.

Banks have the most to gain from developing mobile financial services, because mobile phones offer a low-cost way to reach such a huge market. But banks have a limited understanding of lower-income consumers and what they want. To succeed in this market, banks must rethink their offerings to address the needs of the African consumer and create a cost-effective business model.

For their part, mobile network operators already have a low-cost communications network, some form of agent network, and a good understanding of the low-income African consumer. But the financial services they offer often don’t comply with banking regulations; the offerings of different network operators aren’t very compatible yet; and interoperability is limited.

Market Watch

In this report, we introduce BCG’s Market Attractiveness index, which aggregates our research to reveal the consumer markets and products showing the strongest growth—and growth potential. Our research pointed to the emergence of two potentially important markets. The first is Africa’s rural consumers, who are often overlooked by companies focusing on the continent’s urban populations. The second is Ethiopia, whose economic strength and growth indicate a bright future. Both of these markets are poised to generate increasing consumer demand.

BCG’s Market Attractiveness Index

When will the market for large household appliances in DRC be big enough to justify the entry of a new brand? At what income level will penetration of air conditioners in Nigeria be above 50%? Because the availability of detailed consumer data in many African countries is limited, BCG developed the Market Attractiveness index to provide answers to these types of questions. For consumer products companies hoping to enter new markets or increase their share in existing ones, the index can help identify the most lucrative growth opportunities. For instance, while the markets for clothes, shoes, and accessories in Ghana and Kenya are of a similar size today, Kenya’s market is projected to grow 18% more quickly than Ghana’s over the next ten years. Similarly, although South Africa is currently the largest market for beauty care among the 11 African countries included in this report, Ethiopia will be the fastest-growing market for these products over the next ten years. The index includes estimates of market size—for today and projected forward ten years to 2025—for 19 consumer categories across the 11 countries.

In our survey, we asked respondents to indicate which of 17 household-income brackets their families fit into, ranging from less than $50 per month to more than $7,000 per month. We also asked them to estimate how much money their household spends per month on each of the 19 consumer categories, ranging from recurring expenses such as food and utilities to big-ticket items such as education and health care. We then combined this data, showing how much more—or less, in some cases—households spend on different categories as incomes increase, with 2015 estimated and 2025 projected household-income data by country across defined income brackets. The output is an index that estimates the market size of different categories both today and in the future. (See Exhibit 4.)

Rural Consumers

Given headlines such as “Urban Consumers Will Power Africa’s Rise” and “African Cities in Particular Are Booming,” it’s no wonder that MNCs are focusing their efforts on Africa’s urban markets. With their expanding consumer bases, rising incomes, and relative population densities, cities are indeed the place to start for most businesses. But the continent’s growing rural markets can offer significant opportunities for companies that already have an extensive urban presence and the capital and know-how required to successfully penetrate new markets. “The next million customers will come from there,” says Zunaid Dinath, chief officer of sales and distribution for Vodacom, a regional telecommunications company based in South Africa.

In terms of purchasing behavior, our survey showed that Africa’s rural and urban consumers are quite similar. Rural consumers value quality just as much as their urban counterparts do, and are willing to spend more for better cars, electronics, beauty and baby products, spirits, and certain foods. Demand for household appliances, mobile phones, and clothing is particularly strong. However, spending power differs. The average income of rural consumers across the 11 countries we surveyed is 49% less than that of urban consumers.

We currently see rural markets as a niche opportunity for MNCs that have largely captured the urban opportunity—in sectors such as mobile phones, soft drinks, and banking. We recommend that players in other sectors continue to focus on urban markets and reevaluate the rural opportunity as it develops.

MNCs that are ready to enter rural markets should understand that rural consumers are harder to reach than urban consumers, so the cost to serve them is higher. To capitalize on the opportunity, companies will need to rethink how they market and distribute their products. (See “Traditional Trade.”) Rural consumers are less exposed to the media and marketing methods, and tend to be less trusting of the unfamiliar. Old-fashioned word of mouth and trust building are still the most effective marketing tools. That’s where “zonal champions” come in.

A concept developed by a marketing agency, The Creative Counsel, as a way to reach rural consumers, zonal champions are members of local communities who are hired to represent a brand and to promote products during their daily interactions. The objective is to persuade friends, family members, and neighbors to try something new.

Distribution and logistics challenges are typically cited as principal barriers to reaching rural consumers. Once again, innovative and tailored solutions are the answer. Some companies make it easy for even the smallest shops to market and sell their products by providing signage for stores, creating shipping cases that become compact displays that fit into a smaller retail footprint, offering small package sizes at the right price points, and using wholesalers and other third parties to expand distribution.

Coca-Cola established micro distribution centers (MDCs) to help its third-party distributors in rural areas that are difficult to reach and serve. Although the company’s preferred model is to have bottlers handle direct distribution to all retail outlets, the MDCs are a way for Coca-Cola to adapt to the rural environment. Each MDC gets an exclusive territory franchise, as well as additional support services such as microcredit and loans for trucks and other assets, in addition to training in advertising, merchandising, accounting, and recruiting.

Ethiopia, the Next Frontier

A number of macro trends indicate a bright future for this African country. According to the International Monetary Fund, Ethiopia’s GDP grew by 10.2% in 2015—making it the fastest-growing country in the world. It’s becoming easier to do business there, too. The number of days required to start a business dropped from 46 in 2004 to 15 today, and the cost of starting a business decreased from about $700 to $400. Another good sign: Ethiopia’s government is upping its level of investment, having directed about 15% of GDP toward large infrastructure projects and having doubled health care spending since the late 1990s. Global consumer-products companies are starting to take notice—and action.

Although doing business is only slightly more challenging in Ethiopia than it is in other African countries, starting a business is harder. The government requires higher fees and more capital for start-ups relative to other countries and is strict in its oversight of businesses. Since Ethiopia is a landlocked country heavily reliant on access to the Djibouti seaport, trading across borders is also more problematic. Export times are longer and related costs are higher.

Because of these obstacles, MNCs need patience and persistence to make inroads, but many global leaders in consumer products believe it’s worth the effort. Coca-Cola has designated Ethiopia as its fourth-most-important market in Africa. The company has been in Ethiopia since 1959, now owns two factories, and is investing in three new bottling plants worth a total of $500 million. Greig Jansen, then CEO of the East Africa Bottling Share Company, explained the company’s ambitious plans in 2013: “Our strategy is to have a cold Coca-Cola within arm’s reach for all our consumers in Ethiopia by 2020.”

Beer maker Heineken is also investing heavily to capitalize on Ethiopia’s emerging consumer demand. Founded in 2011, Heineken Ethiopia has seen the country’s beer market double in five years. The company invested $220 million in two bottling plants and launched an Ethiopian brand, Walia. Heineken’s current strategy is to build on its momentum. The company is investing $120 million in a state-of-the-art brewery that will be the largest in Ethiopia and will double the company’s potential output. The next step is to launch the Heineken brand and capture the superpremium market. Jean-François van Boxmeer, Heineken International’s CEO, explains, “We are investing ahead of the curve, and with a long-term ambition to create sustainable businesses. The beer category in Ethiopia has huge potential.”

Consumer sentiment among Ethiopians is also positive. Perhaps because the country’s GDP growth is so strong, Ethiopians feel more financially secure than many other Africans. Their savings rate is the second highest in Africa and it is increasing.

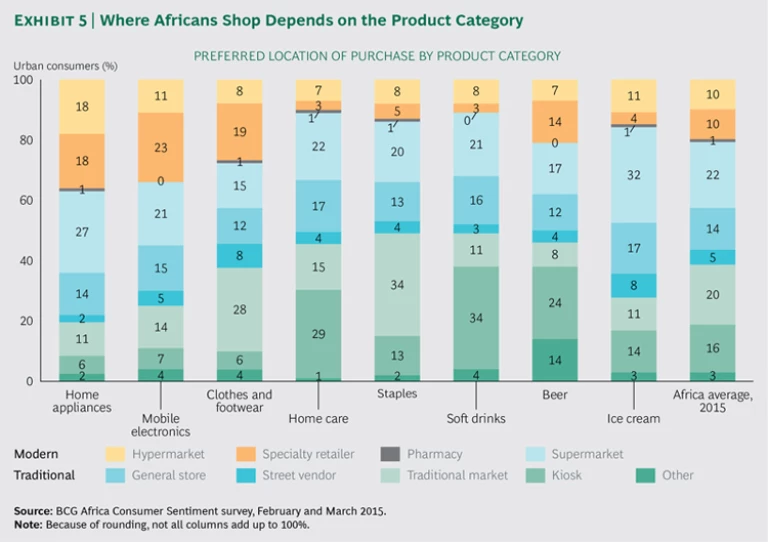

Channel Insights

Where do Africans shop? Traditional trade outlets such as markets, street vendors, and spaza shops still dominate. But modern trade is making inroads—more so in some countries than in others—with 26% of consumer store visits being made to modern trade outlets. Online purchasing is still rare. Where Africans shop depends largely on the product category. (See Exhibit 5.)

South African and Angolan consumers visit modern retail stores more often than consumers in the other countries in our survey, with modern trade accounting for 39% and 34% of visits, respectively. Certain product categories—such as home appliances and mobile electronics—are more often purchased in modern retail stores than are other categories. The DRC, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Ghana have a low prevalence of modern trade, particularly for food and home items.

For a number of reasons—including lack of Internet access, trust issues, and a desire to see and touch a product—online purchasing is rare in Africa. Nigeria’s consumers are the most likely to shop online (25% have done so). But as Internet access spreads and comfort levels increase, online buying will likely grow, as it has in other developing markets.

Traditional Trade

Despite the growth of modern trade in many African countries, traditional trade continues to represent a significant opportunity. In South Africa, the informal market is declining but still represents at least 20% of retail sales in many categories. Although Nigeria has more than 700,000 traditional trade outlets in the soft-drinks category, it has very few of Africa’s most prominent supermarket chains: only 7 Spars, 16 Shoprites, and 2 Game stores. By comparison, South Africa alone has nearly 2,000 Spar and Shoprite supermarkets.

Africa’s traditional trade outlets are notoriously difficult for MNCs to penetrate. For one thing, the huge number of markets makes it hard to track goods through to the final consumer—a problem made even more challenging by a lack of data. The likes of Nielsen or Ipsos do not yet track Africa’s traditional trade. What’s more, the marketplaces are often jammed with vendors and located in remote areas.

How to Make Inroads

To successfully penetrate Africa’s traditional trade, companies must first conduct a census to understand the types and locations of trade outlets in the targeted countries and the differences among them—their size, the products they stock, their customers, and how often those customers shop. The next steps are to assess the potential revenues from and accessibility of each outlet, and to develop a strategy for product distribution that is profitable after factoring in the cost to serve. Then companies should create specific territories and assign each to an exclusive distributor—a trusted partner with deep experience in the region. They should put in place measurable KPIs to ensure consistently high standards of execution, and track performance against those KPIs. As sales are monitored, the distribution model can be updated and improved as required.

Nestlé uses unconventional sales methods to access hard-to-reach traditional trade outlets. The company’s informal distributors walk or use bicycles to deliver Nestlé products to small and micro outlets in far-flung places. These informal arrangements can give MNCs an inside track with small local spaza owners, who would typically need four to five weeks of getting to know outsiders and trusting them enough to carry their goods.

Besides controlling costs and increasing sales coverage, MNCs’ relationships with local distributors can also boost general brand awareness. As one small distributor in South Africa noted, “Nestlé is becoming popular because of us.”

Africa’s growing consumer markets offer enormous potential to MNCs looking for new opportunities. But success requires a deep understanding of the tastes, preferences, and behaviors of the continent’s varied populations. To make inroads, companies will have to target those segments with the greatest potential, rethink how they market and distribute their products, and create tailored solutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Neeraj Aggarwal, Nomava Zanazo, and Abdeljabbar Chraiti for their valuable contributions to this report.