Over the past 18 months, communications between the US and Cuba have improved significantly. The two countries now enjoy diplomatic relations, and President Obama’s recent trip to Havana was the first visit to Cuba by a US head of state in nearly 90 years. Restrictions on trade and travel are easing. Cuba has taken steps toward opening its market and loosening the rules governing private businesses, and it has made overtures toward reestablishing international trade. Both Pope Francis and the Rolling Stones traveled to Cuba during the past year, highlighting the scope of global interest in the country.

All of these changes have created interest and excitement, and many of Cuba’s government ministries are backed up with requests from outside organizations looking to forge ties to the country.

US consumer goods companies see a clear opportunity: Cuba’s economy is growing, yet its people still have very little exposure to consumer products and brands, so it remains one of the last true white-space markets on the planet. At the same time, most US executives know little about Cuban consumers. Economic data about the island’s economy is incomplete, and its retail and distribution networks are opaque. Management teams lack the data they need to properly assess the opportunity.

Recently, BCG has been studying Cuba’s economic evolution, the emerging profile of Cuban consumers, and the potential opportunity for US companies. This article is the second in a series. The first looked at Cuba’s overall macroeconomic development. (See “ What Cuba’s Economic Evolution Means for Multinationals ,” BCG article, April 2016.) A third will analyze the country’s travel and tourism industry.

In our analysis, we examined Cuba’s retail infrastructure and the behavior of its consumers, including their spending trends, brand awareness and purchasing habits, and sources of product information. (See “Methodology.”)

Methodology

BCG surveyed 326 Cuban respondents in Havana (Cuba’s capital and largest city) and an additional 114 in Santiago (a smaller city in the poorer, eastern part of the country) to capture the perspectives of different types of consumers. Responses were anonymous, and all survey participants were responsible for making purchasing decisions for their households. Respondents’ ages mirrored the country’s overall demographics. However, given Cuba’s aging population, we sought to capture a larger proportion of younger respondents, who are considered by consumer goods companies to be more attractive customers.

The respondent base included people who work for the state as well as those in the country’s emerging private sector. We also identified those who receive remittances—such as money and gifts—from the US and those who do not. Because Cuba has extremely limited Internet access, we conducted the interviews in person. For questions related to income and spending, we confirmed which of Cuba’s two currencies applied to each respondent’s answers.

In addition to the survey, we interviewed experts across a range of disciplines in the US, Cuba, and Latin America, and we spoke with Cubans who had recently left the country for the US. Furthermore, we visited the island to study the country’s retail and distribution infrastructure firsthand.

Our research results focus on consumers in urban areas. Overall, we believe that consumers in more rural areas have less purchasing power because of their limited access to remittances from friends and family in the US and less income from private enterprise and tourism.

This study represents one of the first formal studies of the consumer market in Cuba. The retail landscape is still relatively undeveloped, as are the means for gathering market intelligence. We believe that our analysis is directionally accurate, but we also understand that some findings may not be in alignment with the direct or anecdotal experience of people doing business in Cuba.

The results of our research suggest that the opportunity for consumer goods companies in Cuba will likely expand over the next five to ten years, primarily because of a small but growing group of urban, increasingly affluent consumers who have access to private income that supplements their government salaries. Some local factors—such as stiff regulations and a lack of infrastructure—present sizable challenges to foreign companies trying to get their products into the hands of Cuban shoppers, even compared with the challenges of other developing markets. (See “Getting Goods to Market.”) Yet over the long term, and with continued development of the economy, Cuba represents a promising opportunity.

Getting Goods to Market

US companies interested in establishing a footprint in Cuba may find that the process is challenging. The usual first step is to secure a license from the US government. Under the terms of the Cuba embargo, which was established in 1962, all domestic companies seeking to do business with Cuba must gain US government approval. Approvals have been most commonly granted in categories such as food and medical supplies, although, lately, the number of categories and the number of licenses issued overall have been rising. The US government stipulates the amount of product a company can sell. This degree of government control will not change as long as the embargo remains in place.

With a license in hand, companies must work with Cuba’s Ministry of Trade, which controls the wholesale and retail sale of goods. (Companies may get permission from the Cuban government first and then approach the US government. That, however, is not the norm.) Companies may also work with a distributor that already has a relationship with the government, but, either way, the Cuban state makes all decisions, particularly regarding the quantity of goods and how they will be distributed. The quantity is frequently lower than what the US government allows, and such decisions are final. If, for example, supply runs out in October, the product will not be restocked until the beginning of the next year.

The government handles distribution. However, payment systems, logistics, and even transportation infrastructure, such as refrigerated trucks, are all very basic in terms of capabilities. The country’s retail network is split into three primary channels:

- Libreta, or ration book, stores are government-owned sites that sell primarily subsidized food—such as rice, beans, oil, and flour—and basic goods under a system that uses Cuban pesos.

- Government-owned chains such as Cimex (Cuban Export-Import Corporation), TRD (Tiendas Recaudadoras de Divisa), and Cadena de Tiendas Caracol operate independently and sell other food and goods that are not included in the ration system. The government allocates products and sets category budgets for each outlet.

- Some very small private retailers—mainly street vendors and home-based shops—also sell a small array of goods. These retailers are very fragmented and highly regulated. For example, people may sell clothing, but only garments that they themselves have made.

The Macroeconomic Baseline

Cuba has a population of 11 million and, as of 2014, a nominal GDP of roughly $82 billion. Since 2009, the country’s economy has been growing steadily at about 3% per year in real terms. We believe that Cuba will continue to grow at that pace, on average, for the next several years. Factors spurring the growth include continued improvements in US-Cuba relations, increasing remittances from US-based individuals to Cuban residents, and market-based reforms by the Cuban government.

With regard to the long term, we believe that, in order to grow faster, the country will need to address several structural limitations of its economy. For example, much of Cuba’s infrastructure has decayed as a result of underinvestment. The government currently cannot—and does not want to—access funding through international financial institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, or Inter-American Development Bank, whose funding was a key factor in the rapid growth of other formerly closed economies, such as Vietnam’s. And thus far, Cuba’s leaders have been fairly tentative about economic reform, especially compared with former Communist states that took aggressive measures to open up their markets.

The Cuban Consumer Today

The Cuban economy is centralized, and many Cubans work for the government, earning a state salary of, typically, $20 to $25 per month. As a result, purchasing power in Cuba is limited, with more than 75% of Cuban households earning less than $1,000 per year.

The government provides free education and health care, and it heavily subsidizes the purchase of basic food items through a ration card system. A one-pound bag of rice, for example, sells for the equivalent of $0.01. According to our survey, 90% of Cubans use food rations, but the rations are not generally enough to cover all their needs. The limited rations include only very basic items—such as rice, beans, flour, and vegetable oil—and there are frequent shortages.

Cuba’s two currencies play a role in Cubans’ overall purchasing power as well. The Cuban peso (CUP) is primarily used by Cubans, and the Cuban convertible peso (CUC) is pegged to the US dollar and is meant to be used by foreigners. (However, it’s increasingly being used by Cubans, too.) Although the government recently announced that it will unify the two currencies and link the unified currency to the dollar, it has not specified a target date for the change.

The two-currency system has led to an income divide. The segments of the population with access to the CUC currency—including tourism workers (who often get tips), those who deal with foreign businesses, and those who receive remittances—have most of the real purchasing power. Furthermore, depending on the work they do, some members of Cuba’s emerging private sector also have access to CUCs. The Cuban government allows people in certain service professions—for example, restaurant owners, hairdressers, and tour guides—to own their own businesses. These cuentapropistas, or entrepreneurs, have benefitted from market-based reforms that the Cuban government has rolled out over the past several years. The reforms added other sectors to those that qualify for private ownership and allowed cuentapropistas to hire a small number of employees. Many such sectors are in tourism or related industries in which people are often paid in CUCs, and because all such sectors lie largely beyond the government’s economic controls, they are free to price their wares and pay employees more than the standard government salary. Still, cuentapropistas face heavy regulations and taxes that make it hard to build a business’s value over time.

It is worth noting that our survey found that purchasing power is about 25% higher than what has been reported in official data. The country has a large informal economy that is not fully captured in government statistics. For example, in Havana, about 25% of government workers receive additional income from remittances (money, clothing, and other gifts sent by friends and family in the US), along with tips from tourists and similar sources.

In fact, remittances are a central factor of the Cuban economy. Our research found that approximately 40% of Cubans living in Havana receive such remittances. This flow of money into Cuba grew by 15% anually from 2010 through 2014 to approximately $3 billion—the result of both higher caps and a larger population of Cubans living in the US—and could hit $6 billion by 2020. By comparison, Cuba’s net exports in 2014 were estimated at less than $4 billion.

As Cuba’s economy continues to evolve, the income divide between those with access to CUCs and those without is likely to grow. Tourism is growing, as are the number of cuentapropistas and the professions that qualify for private ownership. All three trends will increase the percentage of the Cuban population that receives income from outside formal government channels—and, in turn, augment their purchasing power. By contrast, the salaries of government employees are likely to improve at a more modest pace.

Three Consumer Profiles

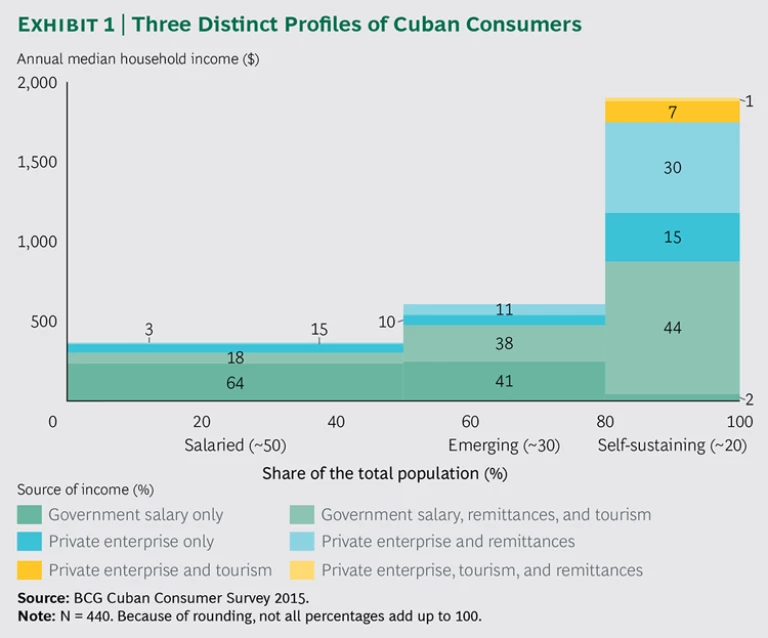

Because the source and type of currency dictate purchasing power for Cubans as much as the absolute value of income, we have identified three consumer profiles. (See Exhibit 1.)

Salaried. Salaried Cubans are paid in CUPs by the government and rarely have access to CUCs either through tourism dollars or remittances. People in this group represent about half of the country’s population—a larger share in rural areas—and they have limited purchasing power. Their median household income ranges from about $300 to $400 per year, and they struggle to meet their basic needs.

Emerging. The emerging group consists of Cubans who are starting to receive income from outside the government. This category includes government employees who draw a state salary and also get tourism dollars or remittances, as well as cuentapropistas. With a median annual household income of $600 to $700, emerging Cubans represent about 30% of Havana’s overall population. They occasionally struggle to obtain the basics but are largely able to make ends meet.

Self-Sustaining. Cubans in the third group might receive a government income, but they do not depend on it. The group includes cuentapropistas and tourism workers who may also receive remittances. Self-sustaining Cubans represent up to 20% of the population in Havana and other cities—and a smaller percentage in less urban areas. They have the highest median household income of the three consumer profiles—$1,800 to $2,000 per year—and although they still use the ration system, they are able not only to cover their basic needs but also to purchase aspirational goods on occasion.

Trends Affecting the Consumer Industry

We believe that the government will continue to roll out market-based reforms over the next several years, raising the number of cuentapropistas and their influence on the economy. Increases in remittances from the US, along with more tourism and higher foreign investment, will also enhance the flow of capital to the island, giving greater segments of the population access to CUCs and leading to higher average household incomes. These shifts will benefit the emerging and self-sustaining groups primarily, and we believe that both groups will grow, not only in income level but also in the percentage of the population each represents.

That said, there are clear uncertainties associated with the consumer market. One concerns demographics. Overall, the Cuban population is aging as a result of low birth rates and the departure of working-age people. More people left Cuba in 2015 than in any other year since the mass emigrations of the Mariel boatlift in 1980. These trends leave Cuba with a hole in its population of young people, who tend to spend the most on consumer goods.

Currency unification is another uncertainty. As noted above, the government plans to unify the two currencies, which is a positive step that will lead to greater transparency about the economy and will partially rectify the income divide. However, currency unification is a tricky process that requires resetting the value of financial assets owned by individuals and institutions. The historical precedents in the region are not reassuring: several Latin American countries—including Venezuela, Argentina, Peru, and the Dominican Republic—that pegged their currency to the dollar subsequently experienced hyperinflation.

Infrastructure is yet another consideration. The US is easing tourism restrictions. However, because Cuba’s airports and seaports have suffered from a lack of investment, there may be limits to how many visitors the country can accommodate. A bigger factor for consumer companies is that it is difficult to get goods into the country, and it’s harder still to move them around the island because of the inadequacy of distribution infrastructure, such as trucks and well-maintained highways.

The biggest source of uncertainty for consumer goods companies is the need to work with the Cuban government for the foreseeable future, through processes that in many cases are highly bureaucratic and slow.

Spending Habits of Cuban Consumers

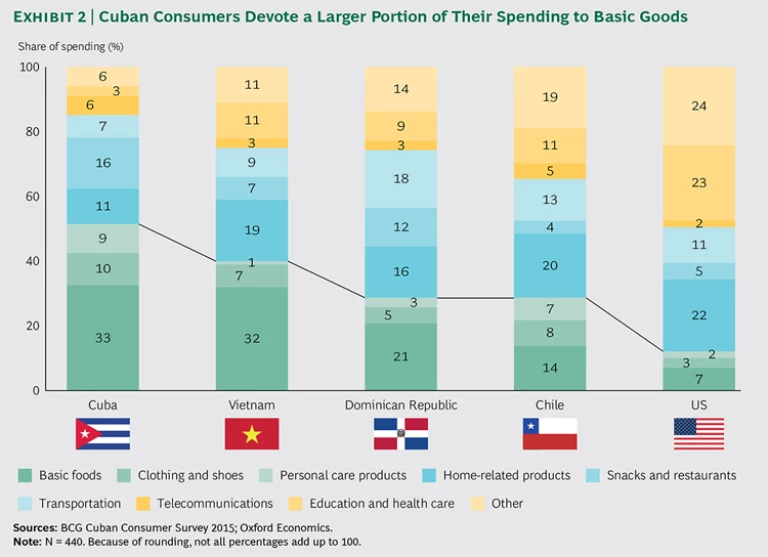

Cuban consumers spend a relatively high portion of their income on basic needs. Overall, about 50% of spending is for basic items such as food, clothing, shoes, and hygiene products, compared with about 30% to 35% in countries such as Chile and the Dominican Republic. (See Exhibit 2.)

This is true even among consumers in the higher-income emerging and self-sustaining segments: they make occasional discretionary purchases in categories such as vacations, transportation, and telecommunications, but they still spend the bulk of their money on basic consumer goods.

In categories such as snacks and eating out, spending among Cuban consumers is higher than in other formerly Communist countries, but it remains comparatively lower in areas such as education and health care because of the Communist system.

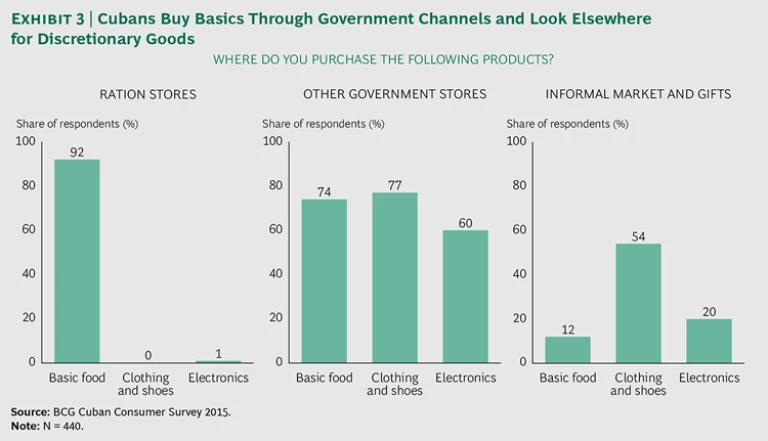

Our research identified significant unmet demand—the result of both relatively low household-income levels and the limited availability of some products—that is often addressed through the informal economy. (See Exhibit 3.) Self-sustaining consumers are the most likely to use such channels to get nonbasic goods.

Limited Brand Awareness

In addition to limited discretionary income, another challenge for consumer companies is that Cuban consumers have relatively little brand awareness.

Most products are sold through the government, and, except for store displays, the country allows no direct advertising or marketing to consumers. In many cases, the most significant factor in purchasing decisions is product availability.

This lack of brand awareness is particularly true in basic product categories, such as food and personal-care products: among home staples, no company has more than 30% brand recognition. As a result, these product categories are wide open: an outside company that can secure the necessary approvals and work with the Cuban government’s heavy degree of distribution control could potentially establish its brands among Cuban consumers. Over time, as income levels, the range of available products, and exposure to the outside world all increase, we expect that brand awareness in basic categories will grow as well.

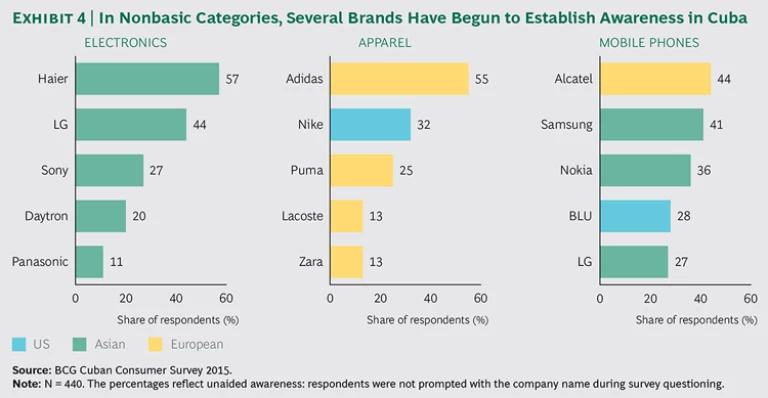

At the same time, Cubans show higher brand awareness for products in discretionary categories such as electronics, apparel, and mobile phones. (See Exhibit 4.) For example, 41% of respondents were able to name Samsung as a brand of mobile phones. These goods are often purchased through informal channels that circumvent the government’s restrictions on advertising. As a result, outside companies in these categories could build their brand through indirect channels.

Sources of Brand Information. The most significant sources of brand information are friends and family abroad, through whom, according to our research, Cuban consumers most commonly become aware of—and acquire—foreign brands. Cuban stores and foreign media, such as television shows, movies, and music, are next in importance.

Another source of brand awareness is El Paquete, or The Packet, a weekly collection of information and entertainment that is disseminated on USB drives. The material typically includes some foreign content (such as US television shows, movies, and magazine PDFs), along with Cuban magazines and a spreadsheet of items for sale. Some Cubans subscribe to a weekly delivery of El Paquete, but consumers can also buy individual downloads.

Other sources of informal commerce are marketplace sites similar to Craigslist that connect buyers and sellers of goods. Purchases from such sites usually require significant coordination, in part because the seller is, in many cases, located in the US. In those situations, the buyer needs to use friends and family in the US to deposit money into the seller’s account. The goods are then delivered in person: someone traveling to Cuba is paid to carry the goods in his or her luggage. Like El Paquete, these marketplace sites are technically illegal, yet the Cuban government has not taken steps to crack down on them.

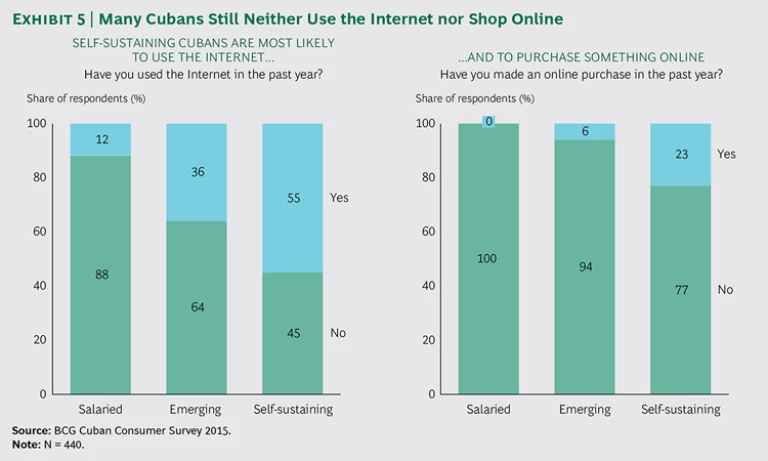

The Effect of the Internet in Cuba. The Internet has the potential to extend brand awareness and commerce. Internet penetration has increased since it was officially introduced roughly two years ago. The number of public hot spots is climbing, and they are reaching beyond urban areas. Some Cubans almost certainly had earlier access through informal channels. Overall, nearly 50% of Havana’s population uses the Internet at least occasionally, and usage rates are rising in line with income levels. It is not unusual to see hundreds of Cubans in a plaza, all using their smartphones. However, service remains very limited and expensive: rates are typically about $10 per hour, or half of the typical monthly government salary. Most people use the Internet primarily to stay in contact with friends and family outside of Cuba.

Among the three segments we identified, self-sustaining consumers are the most likely to go online. However, there is virtually no e-commerce. Even among self-sustaining consumers, less than 25% made online purchases in the past year. (See Exhibit 5.)

Outsiders Face Persistent Challenges

The degree of government control creates clear challenges for foreign companies. Although the Cuban government is implementing reforms to open its markets, thus far, those measures have been limited to peripheral service industries. The country’s retail and wholesale industries are still under government control and will likely stay that way into the near future.

As long as the state retains control over the products that may be sold in the country—and how they should be distributed among retail channels and markets—companies will find that using traditional tactics, it’s challenging to get goods into the hands of consumers. Moreover, because the government sets nationwide prices, companies lack the option of stimulating sales through pricing and promotions. And the lack of advertising makes it difficult for companies to differentiate their products.

Compounding these challenges are the government’s bureaucratic and opaque decision-making processes, particularly those associated with purchasing. Contracts tend to favor the government, and business operations require considerable cash flow. Although the government does pay its bills, it does not always pay promptly—a six-month wait for payment is not unusual.

Our research indicates that in the short term, these challenges aren’t going away. The government will almost certainly retain control over the distribution and retail sales of consumer goods. In the wholesale segment, government-approved local suppliers will likely see slow deregulation. However, imported goods will still face strict oversight, as will all retail channels. The most likely reforms will involve government operations incorporating more private-sector principles—for example, making decisions in a more transparent manner, easing price controls, and introducing some limited competition.

In the longer term, we anticipate that foreign companies will probably have greater access to Cuban consumers—still primarily through wholesale channels. Retail will likely be the last aspect of the market that will open to outsiders. In addition, as Cuban consumers’ brand preferences grow, and the government begins to rely more on foreign companies to meet the demands of the population, officials will need to ensure a level playing field, in part through a consistent application of the rule of law.

Steps That Outside Companies Can Take Today

In the short term, Cuban consumers will continue to spend most of their income on basic goods. In the long term, Cuban consumers in all three segments will see their purchasing power grow and will begin to spend more in discretionary categories. The rate of increase depends on Cuba’s overall growth, which, in turn, depends on how fast the government can open markets and launch other reform measures. The Internet—and access to more information about consumer products—will lead to greater brand awareness.

Companies that want to enter the Cuban market can start by taking several steps today:

- Begin to build relationships. Good relationships with government-approved suppliers in Cuba are critical for getting into the country’s consumer market. These suppliers know how to navigate the bureaucracy and how distribution works. It’s possible—but more difficult—to work directly with the Ministry of Trade, so foreign companies that want to move more quickly should reach out to approved suppliers to establish relationships.

- Establish your brand among expatriate Cubans. Marketing and advertising aren’t allowed in Cuba, but it’s possible to build a brand indirectly through Cuban expats. For example, companies can connect with the large Cuban population in South Florida and can use expats as a conduit to reach Cuban consumers through remittances, websites, and El Paquete. And as Internet penetration grows in Cuba, companies can use the technology in similar fashion to connect with the expatriate population and slowly increase awareness of their brands among Cubans. In particular, the Miami neighborhood of Hialeah has an extremely concentrated Cuban population, and smart companies are marketing to newly arrived Cubans there, specifically anticipating that they will pass word back to their family and friends still on the island. (We witnessed a similar effect in China following the reestablishment of ties with the US, as well as in parts of Africa and India that have quickly adopted mobile phones.)

- Take a long-term view. Companies that take a long-term view can position themselves to capitalize on Cuba’s growth. This applies particularly to distribution. Getting goods onto store shelves is extremely difficult now, but by working with established distributors on the island, Cuba’s government, or both, companies can start to gain knowledge, establish a presence with consumers, and build relationships that will be critical as the economy slowly opens to outsiders. It will not be easy, given the relative lack of sophistication in distributor capabilities, but companies can work with local distributors to help build up the basics. (See “Unconventional Approaches to Access the Cuban Market.”)

Unconventional Approaches to Access the Cuban Market

Given the constraints on doing business in Cuba, foreign companies need to take a less traditional—and longer-term—approach to building their businesses there. Several have already established a presence among Cuban consumers:

- Heineken. Heineken has adopted a less traditional approach, ceding control of distribution to the Cuban government to build brand awareness among consumers. The company has brought refrigerated trucks to the island and essentially given them to Cuba’s Ministry of Trade to use according to its priorities. This approach has helped the company establish a presence on the island and forge relationships that could expand as Cuba’s economy opens. It also has used point-of-sale displays and branded events to help it further establish the Heineken brand among Cuban consumers.

- Adidas. Among brands we tested, Adidas was the most recognized on the island, thanks largely to Fidel Castro’s preference for the company’s tracksuits. He so loves Adidas tracksuits that he has worn them to meetings with foreign dignitaries, including Pope Francis in late 2015. Although Adidas products are not broadly available in Cuba, Castro’s implicit endorsement has raised the Adidas profile and stimulated demand for Adidas goods from outsiders who send things into Cuba, either as remittances or through informal channels.

- BLU. A mobile-phone manufacturer based in Miami, BLU sells low-cost, unlocked phones throughout the Caribbean and Central American market. Although the company doesn’t distribute its products in Cuba, it enjoys high brand awareness (28%) there because of the Cubans in Florida who purchase the phones in Miami and send them to friends and family back home. Through this indirect approach, BLU has become the fourth-most recognized mobile-phone brand in Cuba, ahead of multinational players such as LG.

The Cuban consumer landscape is still relatively undeveloped, but conditions are steadily improving. As the government continues to liberalize segments of the economy, the US eases restrictions on trade and travel, and incomes increase among Cuban citizens, the opportunity for consumer companies will grow. In the short term, success requires working directly with the Cuban government and giving up control of, for example, distribution. In the longer term, companies can begin to forge more direct ties to consumers—in part by building brands through unconventional channels. Like most other newly emerging markets, Cuba will be a turbulent ride for the next several years, but it will ultimately reward companies that are able to ride out the bumps.