Companies looking for growth in slowing Asian economies should aim for the upper middle class. There are already about 150 million upper-middle-class consumers in the developing countries of Asia, accounting for more than $3 trillion in spending annually. Their number could easily swell by 100 million or more in the next few years.

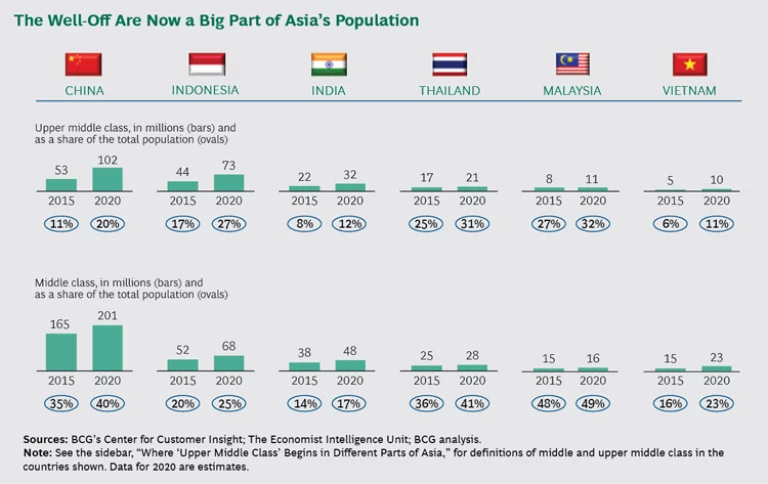

In China, for instance, more than one in ten households now qualify as upper middle class. That proportion will roughly double by 2020, according to BCG’s analysis. The upper middle class already accounts for a quarter of the population of Thailand and more than that in Malaysia. As in China, this segment is growing especially quickly in Indonesia and Vietnam.

Clearly, Asia’s upper middle class is a buying segment that companies both inside and outside the region should be looking at. (In this article, references to Asia are shorthand for the developing countries of Asia.) BCG analyzed six countries that are still considered to be developing—China, Indonesia, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam—to understand the impact of consumers with higher-than-average incomes. (See the exhibit, “The Well-Off Are Now a Big Part of Asia’s Population.”) While these countries still have many households below the middle-class level—varying from one in four in Malaysia to more than three in four in India and Vietnam—there are also an increasing number of well-off households. They include a tiny sliver (likely less than 2%) of the very rich and the expanding segment that we are calling the upper middle class.

Resilient Consumers

The upper middle class’s emergence in Asia helps explain why consumer spending in many of these countries hasn’t decelerated as much as the countries’ overall economies. Economic growth in China, Indonesia, and Malaysia has slowed in recent years. But if the slowdown has affected the region’s upper middle class, it’s hard to tell.

China’s upper middle class is expected to account for $3.8 trillion in urban spending by 2020—more than double its current level, according to a recent study by BCG’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI). This segment could represent two-thirds of all Chinese urban consumption by then, versus about half today. (See The New China Playbook , BCG Focus, December 2015.)

Signs of the upper middle class’s optimism also came through in the CCI’s survey. About three in five upper-middle-class consumers in Indonesia and Thailand said they felt secure about their financial situation, and almost half believed their ability to spend would not be affected by global economic uncertainty.

Shopping and Spending Habits

Asia’s upper middle class isn’t monolithic. There are subtle differences among countries, such as greater brand loyalty in China compared with Indonesia; the types of retail shops that upper-middle-class consumers frequent (for example, more traditional channels—including mom-and-pop shops—in India versus branded retail stores in Thailand); and the extent to which the upper middle class shops online. (China is the furthest along in e-commerce revenues, with most other emerging Asian economies far behind.) In our view, there are also differences in the levels of household income needed to qualify as upper middle class. (See “Where ‘Upper Middle Class’ Begins in Different Parts of Asia.”)

WHERE “UPPER MIDDLE CLASS” BEGINS IN DIFFERENT PARTS OF ASIA

The Asian countries that are the basis of this article report income levels differently, and trying to compare them is challenging. For instance, while some countries look at annual household income, others use less familiar metrics, such as spending on a variety of items.

BCG has come up with its own income- class categorizations. Income levels are shown in dollars to allow for comparisons between countries.

China

Middle class: Urban households with annual disposable income of $8,000 to $20,000. Upper middle class: More than $20,000.

India

Middle class: Annual household income of $7,500 to $15,000. Upper middle class: More than $15,000.

Indonesia

Middle class: Annual household spending of $1,800 to $2,600 on a “basket” of items that include food, utilities, communication, and transportation. Upper middle class: More than $2,600 in spending on these items.

Malaysia

Middle class: Annual household income of $8,600 to $20,000. Upper middle class: More than $20,000.

Thailand

Middle class: Annual household income of $5,000 to $10,000. Upper middle class: More than $10,000.

Vietnam

Middle class: Annual household income of $8,000 to $16,000. Upper middle class: More than $16,000.

But more striking than the differences are the similarities. To begin with, upper-middle-class consumers in Asia, no matter the country, are generally more sophisticated than their middle-class counterparts. They have greater exposure to outside influences and tend to be early adopters of new concepts. They use credit cards more than the middle class.

Not surprisingly, given its higher income, the upper middle class spends more freely than the middle class. For instance, the average upper-middle-class Vietnamese spends about 87% more annually on travel and vacation than the average middle-class Vietnamese. In India, the difference between upper-middle-class and middle-class spending on travel and vacation is about 62%. BCG’s research suggests that there are similar differences in travel spending between these two classes throughout developing Asia.

One can get a sense of the spending differences in other discretionary product areas by looking at the upper middle class’s behavior in China. For every $1 spent by the middle class on cosmetics, upper-middle-class consumers spend $1.60. For every $1 spent by the middle class at restaurants, China’s upper middle class spends $1.59.

Asia’s upper-middle-class consumers in general do more shopping outside their home countries than middle-class consumers do. And in most of the Asian countries that BCG looked at, the upper middle class is becoming more dispersed: it is no longer found only in tier 1 cities (a government classification given to cities with certain levels of economic development, among other things). Tier 2 cities, such as Zhuhai in China and Padang in Indonesia, are increasingly wealthy and connected to the internet, and their residents—more of them now upper middle class—can easily travel to other countries.

Upper-middle-class consumers in Asia are more willing than the middle class to pay for premium-quality goods and services that enhance their sense of well-being. Such goods could be dairy or other food products from New Zealand, cosmetics or skin care products from Japan, or leather goods from Europe. However, not all high-end products are popular with Asia’s upper middle class. Upper-middle-class consumers in the region are willing to trade up and spend more only if they are convinced of the technical, functional, and emotional benefits of a product or service. In fact, they can be quick to complain and discredit a product or service provider if they encounter low quality, misrepresentation, or another indication of poor value.

How to Compete for Asia’s Upper Middle Class

If companies are to win over this valuable consumer segment, they should consider three actions.

Taking Advantage of Digital Tools. Digital media and e-commerce are powerful ways to reach the upper middle class in Asia. These consumers tend to use social media to advocate for brands they like. They also use social media to figure out which products to buy next.

The digital habits of the segment haven’t been lost on global companies. Burberry and Louis Vuitton are already active on the Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo; both also have official accounts on the popular mobile messaging service Weixin (known outside China as WeChat). The perfume and cosmetics site Rose Beauty was launched in China in 2010 by Lancôme and now has more than 4 million subscribers.

And, as is the case with affluent consumers in the West, upper-middle-class consumers in Asia often look at a product online as well as offline before deciding whether to buy it. E-commerce can also fill in gaps in supply availability. After all, a product not available through any retailer in a smaller city can often be ordered on a website and delivered directly to the customer.

Anecdotal evidence suggests there is already a lot of online commerce in tier 2, tier 3, and lower-tier Asian cities—much of it involving upper-middle-class consumers. For instance, in the first half of 2015, 45% of premium skin care sales on Alibaba’s Tmall came from consumers in cities that don’t have physical stores in which those products are sold, according to Alibaba’s research arm. The Economic Times recently quoted Amazon as saying that more than half its orders for luxury brands (including Tumi, Versace, and Roberto Botticelli) in India were coming from smaller cities such as Jaipur, Indore, and Coimbatore.

Thinking Globally as Well as Locally. Affluent Asian travelers bring their overseas experiences home, and their cultures shape their expectations when they travel abroad. Many makers of luxury brands have begun to cater to these consumers and have been hiring more retail personnel who speak Asian languages for their stores in locations popular with Asian tourists, such as Paris.

Upper-middle-class travelers frequently return to their home markets with new interests. When Thai consumers find something they like while traveling abroad, they often write about it on Pantip, the widely used Thai-language discussion forum. The buzz about a product like Tokyo Banana (a Japanese snack) or the roasted duck from London’s Four Seasons Chinese Restaurant creates interest in these products, boosting their popularity in the domestic market. Local Thai companies then look for ways to offer similar products.

Retailers and brands can take advantage of this phenomenon by staying on top of traveler trends and making sure their brand image and messaging are consistent across all channels. Some companies might even want to introduce changes in their organizations that make it easier for them to serve Asian upper-middle-class consumers, regardless of which countries the consumers happen to be in.

Targeting the Younger Generation. The Asian upper middle class can be viewed as two subsegments: those below 35 and those above it. The distinction is important because the young upper middle class represents the most promising part of the segment. These consumers spend an average of 40% more than older members of the segment. This is true across a broad range of products, including digital cameras, electric razors, and cosmetics.

Not surprisingly, younger upper-middle-class Asians are more digital savvy than older ones. That means an investment in digital tools and capabilities, as mentioned above, could be particularly effective in reaching them.

For many luxury companies, it may make sense to develop two different brands: one with broad reach that attracts the majority of upper-middle-class consumers and a more narrowly focused brand that appeals to the younger subsegment.

Targeting a Segment, as Opposed to a Region

In deciding how to approach the still-developing markets of Asia, companies are sometimes too reactive—expanding their footprint at times when a particular country’s gross domestic product is surging, and pulling back during slowdowns. The less-than-stellar results that many companies have achieved in these markets are a reminder that geographic expansion decisions shouldn’t be made on the basis of GDP trends alone. Companies need to look below the surface of economic data to understand where the best opportunities lie, and use that analysis to guide their decisions and strategies.

Asia’s upper middle class is emerging as a powerful economic force—sophisticated, influential, increasingly wealthy. Some companies have already taken steps to capitalize on the opportunity. More will undoubtedly do so—for good reason: this is a market that will pay off handsomely.