This article is an excerpt from Global Leaders, Challengers, and Champions: The Engines of Emerging Markets (BCG report, June 2016).

2016 BCG Global Challengers

- Global Leaders, Challengers, and Champions

- Meet the New Challengers

- How Challengers Have Achieved Global Leadership

- Competing for the Future

The recent struggles of emerging markets are so well known that it can be hard to distinguish the fast-growing trees from the forest. Despite the slowdown in macroeconomic growth, the drop in commodity and currency prices, the crash of equity markets, and the rise of geopolitical risks, the top companies from these markets have kept on expanding overseas.

The economies of some emerging markets may have paused, in other words, but not their strongest and most global companies. The global challengers, BCG’s list of 100 rapidly globalizing companies from emerging markets, are doing just fine.

BCG published its first list of global challengers ten years ago to highlight the achievements of companies that, in the words of the accompanying report, were “changing the world.” If anything, we underestimated in that report the future potential of the global challengers—and the larger group of successful emerging-market companies to which they belong. (See “A Tale of Three Markets.”) In this, the tenth anniversary of that inaugural list, we look more broadly at emerging markets and the dynamic companies that they produce. These include a group of nearly 1,500 companies we call “champions,” which are smaller than the challengers but still growing and expanding impressively. Collectively, the challengers and champions are powering ahead, undaunted by the concerns of Western analysts and commentators.

A TALE OF THREE MARKETS

In the last several years, companies from emerging markets have grabbed market share from multinationals in several key categories within countries. Here are just three examples:

- Handsets in China. Local players, notably Meizu, Oppo, and Xiaomi, increased their share of this expanding market from 19% to 57% from 2009 through 2014. Multinationals grew handsomely, at 24% annually, but local players grew more than twice as fast.

- Cement in Kenya. Multinational cement makers increased their revenue by 8% annually in Kenya from 2009 through 2014, so they may think they are doing well. In fact, their market share dropped from 55% to 40% because local companies are growing more than three times faster.

- Business Process Consulting in India. From 2006 through 2014, the market share of multinational business process outsourcers dropped from 85% to 61%, while Indian companies more than doubled their global market share. Indian BPOs, such as Tata Consultancy Services, have grown at three times the rate of similar multinational companies.

Despite the recent slowdown, emerging markets have benefited tremendously from years of compound growth. For example:

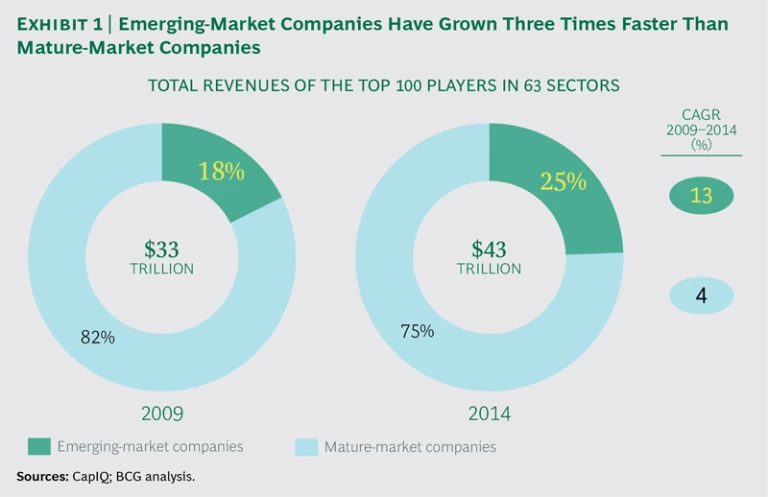

- The top companies from emerging markets grew three times faster than their counterparts in mature markets from 2009 through 2014. (See Exhibit 1.) From 2005 through 2014, the average revenues of the largest emerging-market company in each of 63 industrial sectors expanded from $15 billion to $43 billion. Revenues for Huawei, for example, ballooned to $61 billion in 2015, a 37% increase from the prior year. In IT services, India’s Tata Consultancy Services and HCL Technologies have achieved double-digit growth almost every year.

- In sectors as varied as household appliances, construction and engineering, industrial conglomerates, construction materials, and real estate development, companies from emerging markets have captured global market shares exceeding 40%. For example, the three air conditioning manufacturers with the largest market share in the world are China’s Gree, Midea, and Haier.

To be sure, the road ahead will be more challenging than the one just traveled. Despite the growing middle class and increasing disposable income in many of these markets, global challengers are not immune to macroeconomic forces. They cannot necessarily count on the purchasing power of mature markets to fuel growth or on foreign investors to fund their capital needs. More than $500 billion of net capital flew out of emerging markets in 2015. Commodity players cannot depend on China’s once insatiable appetite for raw materials.

Still, we are bullish on the long-term growth of many of these markets and even more so on the homegrown companies they have produced. Global challengers know how to win in volatile and uncertain times.

These companies are still developing world-class capabilities. And unlike ten years ago, when their primary competitors were multinationals, global challengers today face a new generation of local competitors. Finally, both the challengers and their homegrown competitors are vying for a pool of local revenues that is expanding less quickly, forcing them to seek growth elsewhere. Given these headwinds, global challengers—and companies that aspire to that status—must focus equally on growth and competitiveness. We still expect the overwhelming majority of them to thrive in this new world order. They are proven winners.

Winning Ways

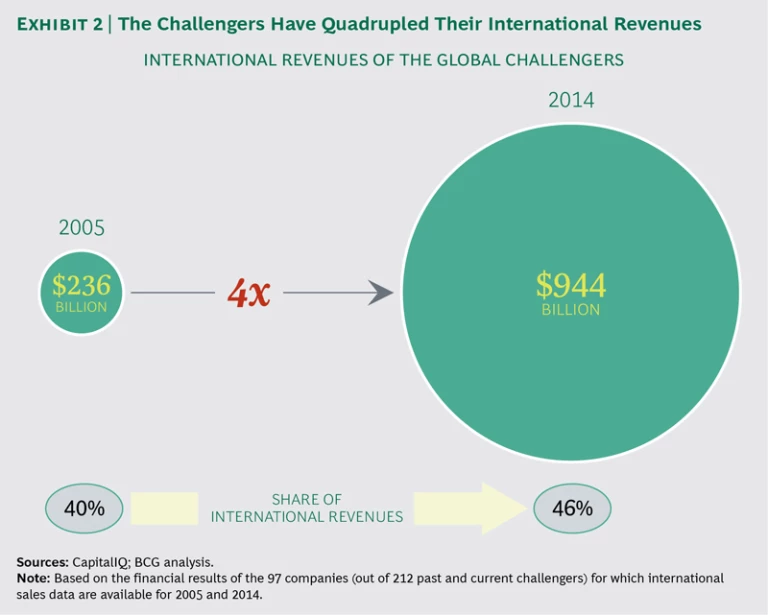

Ten years ago, we anticipated that the global challengers would become potential competitors, customers, partners, and M&A targets. We also predicted that they would “radically transform industries and markets around the world.” On both counts, the global challengers have stood the test of time. They have moved into the global spotlight by dramatically increasing their share of overseas revenues. (See Exhibit 2.) And they have reshaped the landscape of their industries and of key geographic markets.

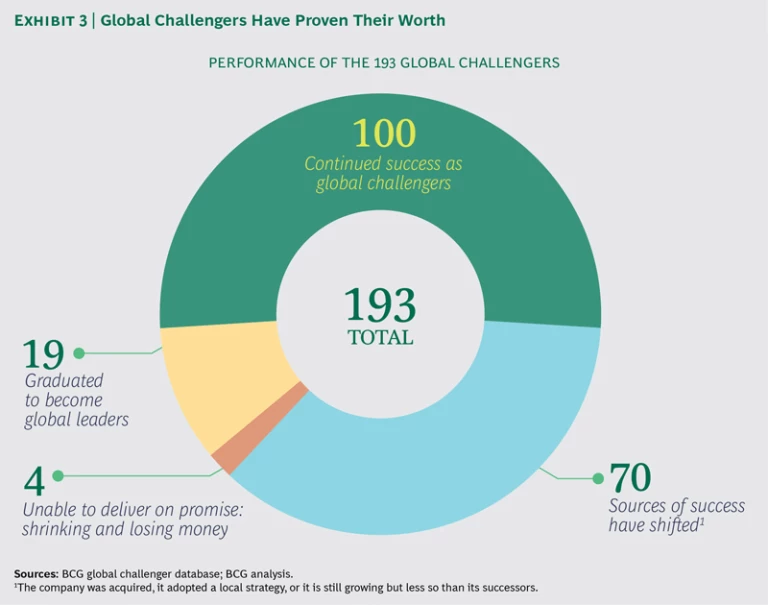

The remaining challengers that we identified in past reports are not standing still. Most of them continue to be challengers. In other words, they are still growing and globalizing impressively.

Of course, given the volatility of emerging markets, not all challengers have remained at the top of the globalization game. Some have been acquired or have refocused on local markets. Others are still growing but less so than their successors. A few have suffered lapses in corporate governance that were not initially evident. A vanishingly small number have been flat-out disappointments. Only 2% of the 193 global challengers are now losing money and shrinking in size. In other words, 98% of the challengers are still strong businesses. (See Exhibit 3.)

MEET THE GRADUATES

Global challengers live in a sort of halfway house between their home markets and the global economy. They have global aspirations and global footprints but not necessarily global leadership. Graduates, on the other hand, have made the full transition. They have annual sales exceeding $10 billion, are top-five players in their industries, generate at least half their revenues overseas, and expect to maintain a global footprint and operations. Here are the seven new graduates.

- América Móvil (Mexico). This telecom operator has the third-largest number of mobile subscriptions globally and a 43% share of the Latin American mobile market. With operations in 25 countries, the company plans to increase its wireline presence in Eastern Europe.

- Gazprom (Russia). This energy company is the largest producer of natural gas in the world, with a 19% share. It expects 30% of its revenues to come from Asia by 2025.

- Hindalco (India). The third-largest producer of aluminum globally has cushioned itself from the financial effects of the collapse in commodity prices through diversification. In particular, its copper business and its 2007 acquisition of Novelis, a producer of rolled aluminum based in the US, have helped smooth out the commodity cycle.

- JBS (Brazil.) The largest meat producer in the world has expanded globally through acquisition. It has production facilities in 24 countries and sales in more than 300 countries.

- Johnson Electric (China). This supplier of motors and other motion components for the auto industry has plants in China, India, Mexico, the US, and several European countries. It also has innovation and design centers throughout Asia, Europe, and North America.

- Tata Consultancy Services (India). This IT outsourcing and consulting company grew by 15% last year, compared with less than 2% for the overall industry. It has 29 customers, each with annual billings exceeding $100 million, and offices in 46 countries.

- Tata Motors (India). India’s largest car maker is also the second-largest bus maker globally and the fourth-largest truck maker. Tata bought Jaguar Land Rover in 2008 and turned the brand around; it now has the largest share of the UK auto market.

While becoming a global challenger is a worthy achievement, the ultimate goal for many companies is to “graduate” from the list, effectively becoming peers of mature-market multinationals whose rule they have disrupted.

Of the 193 global challengers selected over the past ten years (and described in six previous reports), 19—or 10%—have become global leaders.

If the last ten years represented the coming of age of emerging markets, then the overall list of 193 challengers reveals trends that have stood the test of time. We identify several below.

The Global Footprint of B2B Companies

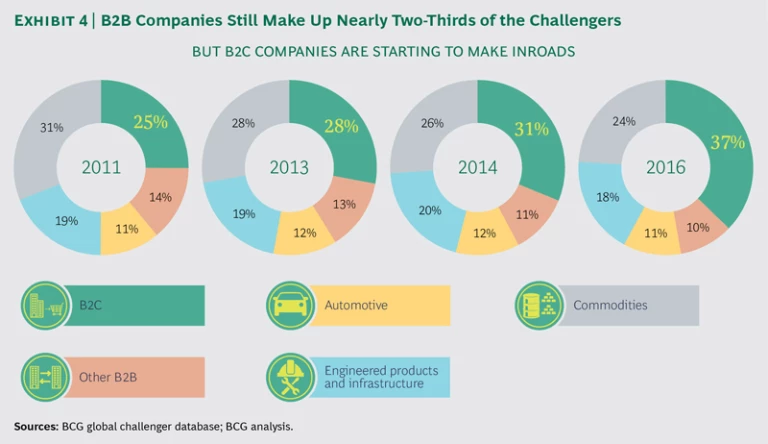

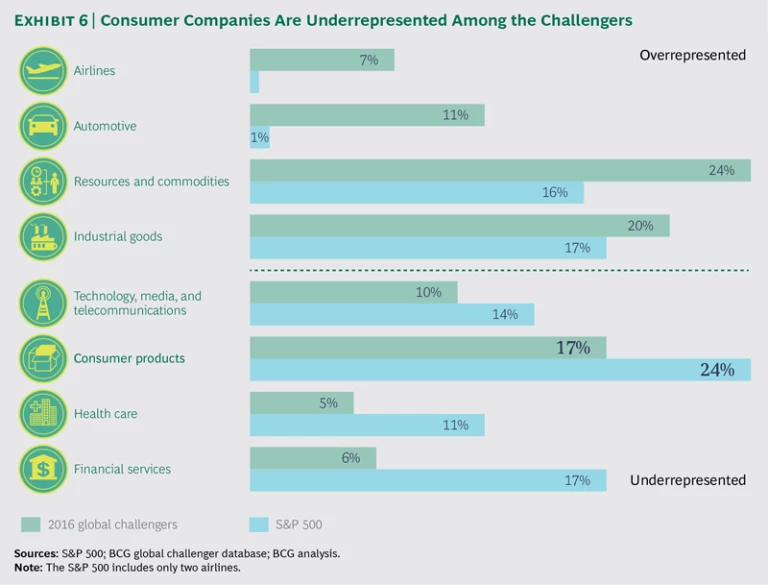

On past lists, companies that sell to other companies have done better than consumer companies, constituting between 63% (the current percentage) and 75% of the global challengers. (See Exhibit 4.) Generally, B2B markets are more global than B2C markets. The similarity of business needs for goods and services across markets allows these companies to build global scale more easily than many consumer-oriented companies.

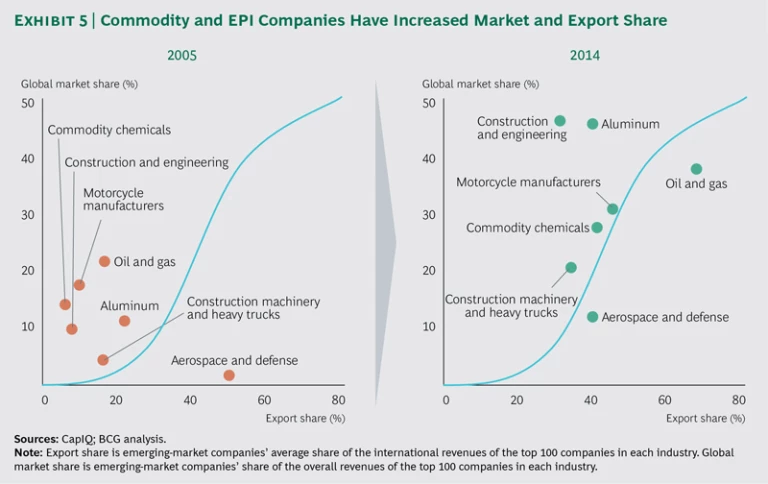

In particular, commodity companies and engineered products and infrastructure (EPI) companies—a broad group that encompasses construction and manufacturers of heavy industrial equipment and wind turbines, for example—have excelled at globalization over the past ten years. (See Exhibit 5.) But their sources of success are different.

- Commodity Companies. Commodity companies from emerging markets have succeeded globally by keeping their costs low while achieving global quality standards. They have also benefited tremendously from China’s thirst for natural resources.

- EPI Companies. EPI companies break into two broad groups: construction companies and heavy-equipment manufacturers. The construction companies have benefited from massive spending in their home markets, which they have parlayed into success in other emerging markets. Heavy-equipment manufacturers, on the other hand, started at the low end to acquire scale and then invested in R&D and innovation as a way to expand into new segments.

A word of caution: the end point for most of our analysis in this report is 2014, before the drop in commodity prices and the slowdown in infrastructure spending, so it remains to be seen how the composition of future lists of global challengers may change.

The First Wave of Consumer Challengers

Consumer companies historically have been underrepresented on the global challengers list. (See Exhibit 6.) There are plenty of successful consumer-oriented companies, but relatively few global fast-moving-consumer- goods companies. Instead, many of the global consumer companies based in emerging markets have relied on low costs (the Chinese appliance makers, for example) or on access to commodities (the Brazilian and Southeast Asian food manufacturers).

A few have also emerged from capital-intensive, highly regulated industries, such as airlines and telecoms. Middle Eastern air carriers, for example, have benefited from their hubs in an important long-haul region that was less affected by the global financial crisis, while the Asian and Latin American airline challengers have offered better routes and lower costs than most of their regional competitors.

Fast-moving-consumer-goods companies, on the other hand, require superior consumer insight, branding, and go-to-market execution—skills that many emerging companies are just starting to master. To be fair, many consumer companies may not feel the need to expand globally. First, they can find growth close to home. The swelling middle classes in their own and nearby markets may be providing them with ample opportunity to become regional powerhouses, as we discuss later. Second, consumer companies that are privately owned may simply not want to take the risks associated with globalization when they are doing fine close to home.

But, as we will see in the next chapter, the market is in flux. As these companies mature, they are starting to achieve and even exceed the capability levels of multinationals.

The Strategic Importance of M&A

Challengers and other leading emerging-market companies increasingly are engaging in M&A as a way to achieve key strategic goals. Often they are trying to acquire scale, new markets for growth, intellectual property, and critical capabilities. Deals are no longer simply vehicles to secure natural resources but catalysts to re-engineer companies to compete more effectively in the global economy. For example, China National Chemical Corporation’s $43 billion offer to buy Syngenta, a Swiss seeds and pesticide company—if successful—would help China boost agricultural production and feed its population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the dozens of colleagues around the globe who assisted with the research and analysis for this report. Several partners, consultants, and knowledge team members made contributions in each local market covered by the report. The authors would especially like to thank Nivedita Balaji, Sumit Dora, Mohandass Kalaichelvan, Nicolas Meyer, Vivek Sharma, Praipim Vutivijarn, Brigitta Wastuwidyaningtyas, and Hannah Wang for research and analysis; and Mark Voorhees for writing assistance.