In market after market worldwide, an increasingly popular breed of retailers is proving an old credo wrong. Stores such as Aldi, Lidl, Trader Joe’s, and Mercadona, which offer more targeted assortments than traditional grocers do, are showing that shoppers don’t have to choose between value and quality.

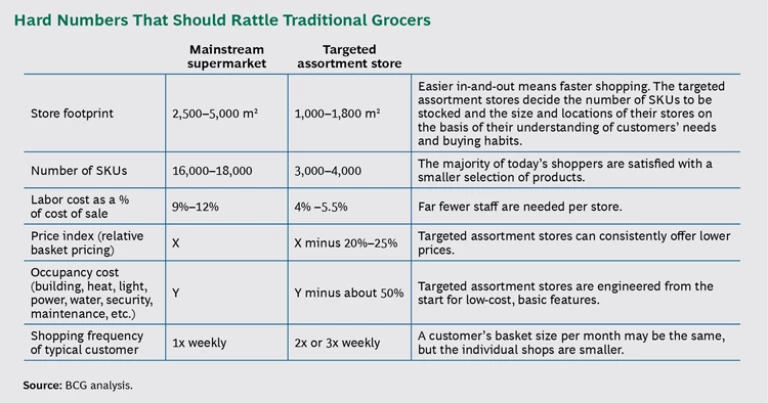

Mainstream grocers need a fresh approach to serving customers and running their businesses—an approach that goes beyond tactical bottom-up moves at the store level. (See “ The Retail Revival Series: Succeeding with a Store-Led Strategy ,” BCG article, September 2014.) They have long positioned themselves as champions of assortment and value as well as beacons of quality. But they have been finding it increasingly difficult to settle on the right positioning (and to drive top- and bottom-line growth). That’s because the needs and behaviors of shoppers have been shifting—and because the targeted assortment stores have recognized and responded to those shifts more quickly, upsetting the economics of the grocery trade in the process. (See the exhibit, “Hard Numbers That Should Rattle Traditional Grocers.”)

These days, far fewer families shop for what they’ll need next month. Instead, they take shorter, more frequent shopping trips, increasingly to smaller stores nearby that are easier to get in to and out of than the larger-format supermarkets and hyper-markets that, in the 1980s and 1990s, held the high ground on price and selection. Online retail further undercuts the “one-stop shopping” advantage and is well-suited to today’s consumers.

The relative newcomers in the grocery industry—firmly established in Europe and rapidly making inroads in the US, Australia, and elsewhere—were quick to seize the opportunity. With their smaller footprints, superior value, and steady additions of fresh and appealing products, they have won over more and more mainstream shoppers—and they’re keeping them. Why shop elsewhere when you can get almost everything on your list for 20% less and navigate the store more quickly?

The targeted assortment retailers have not been standing still. They have been adding services such as in-store butchers and products such as cage-free eggs, champagne, and snow crab claws at surprisingly low prices—items that once were sold only by retailers catering to affluent shoppers. Interestingly, more than a few of those well-heeled customers now shop at the targeted assortment stores.

Traditional Retailers’ Responses Have Fallen Flat

Traditional retailers were quick to slap “discounter” labels on the newcomers, dismissing their collective moves as a low-quality play. But the incumbents have finally seen how fundamental are the shifts in customer demand and how different are the underlying proposition, operating model, and economic model that characterize the targeted assortment retailers. As a result, the mainstream grocers have realized that many of their initial responses have actually widened the gap. Below are some of the moves they have made—with limited impact.

Adding Products. As their sales volumes have declined, many retailers have added range to try to stimulate sales and satisfy suppliers during negotiations. Variety appeals to shoppers, of course, but 176 types of salad dressing—an actual SKU count at a leading US supermarket chain—is probably excessive. Wide, undifferentiated ranges dilute sales per product line, make stores more cluttered and harder to navigate, and add costs throughout the value chain.

Many retailers have also launched “discount” private-label lines. Yes, this has given them a lower entry price point in the categories, but it has failed to match the quality-price balance of the targeted assortment grocers. Worse, the private-label push has diluted sales per SKU and has created price and quality inconsistencies in many categories between different private-label tiers.

Boosting Promotions. Many traditional retailers have increased promotions to spark short-term sales, compensate for lack of price competitiveness, and please suppliers during negotiations. These days, it’s not uncommon for retailers to have upward of 40% of their sales come from promotions. However, the added promo typically disrupts shoppers’ perceptions of price and undermines their trust in the retailer. And it often inflates the shelf price and piles on operating costs across the retailer’s value chain.

Cutting Labor. Many grocers are cutting team members’ hours to relieve pressure on the bottom line and free up funds to invest in price cuts. But the consequences are quick to appear, in the form of deteriorating service levels, and shoppers soon notice. Associates who are disengaged or too busy are poor ambassadors for a store’s brand; if they’re surly or rude, many customers will shop elsewhere.

While many factors shape grocery operations, short-term moves such as the ones we’ve described can be a “triple whammy”—a detriment to shoppers, suppliers, and retailers. More and more consumers see traditional retailers as expensive, complex, and unengaged. Suppliers experience declining volume, more complexity, and lack of scale per product line. And retailers see sales volumes sliding and operating costs heading in the wrong direction.

The Right Way to Rethink Operating Models

So, how should retail executives respond? Leading grocery retailers that have successfully reinvented their operating models emphasize the following actions:

-

Revisit the customer value proposition. A crystal-clear value proposition demonstrates a deep understanding of a store’s target customers and a high degree of confidence in being able to meet their expectations. Note that “value” in this context does not simply mean “discount” (although it could); instead, it refers to whether the customer feels that the store is meeting or exceeding his or her expectations.

BCG identifies three priorities for retailers that are reinventing their value propositions. The first is developing a clear understanding of customer demand, priority segments for the retailer, and its mission or purpose.

The second priority is clarifying the role and intent of each product category. By “role,” we mean the core purpose of a category as determined by customer insight, market attractiveness, and economics, and by the strategic importance to the grocer. The “intent” of a category refers to the direction for resource allocation and prioritization; it is based on relative market share, relative growth, and profit margin.

The third priority is ensuring that the right type of store is in the right location. To be sure, store types and networks can’t be changed overnight, but retailers can quickly adjust macro spaces within their walls, and micro spaces within categories, in order to deliver a desired customer experience.

-

Get ready for category reset. For too long, retailers have either outsourced the category management process to major suppliers or have done little more than match competitors’ actions in that respect. By “resetting” their categories, retailers can regain control of all aspects of them, including range, own brand, price architecture and level, trade strategy, merchandising principles, and supplier strategy and terms. A reset should also involve operational considerations such as pack size, stock levels, availability, and waste.

The reset process should be guided by a clear understanding of customer behavior and needs in the category, competitive positioning, and the economics of delivering the category proposition.

Range is an essential consideration for retailers facing rivals with lower SKU counts, such as Lidl and Biedronka. To compete, it’s crucial to curate SKUs—carefully matching them to what most shoppers need most often—instead of adding more of them.

The reset process depends on the category. For fresh categories—often the key to driving overall customer perceptions—the process could result in more range, higher service levels, and more everyday low pricing. For basic packaged categories, the reset could result in big reductions in range and suppliers, a move to merchandising units, and a mid-low pricing strategy

-

Streamline the total business operating model. Any reinvention initiative will require a hard look at end-to-end operations, from supplier to shelf. Trade-offs have to be made between investing in customer service and the funds required to pay for that while supporting the format’s economic model. An efficient operating model is the basis for long-term price competitiveness, and the differences between retailers can be significant. For example, less efficient retailers can have a total loss (due to waste, shrink, and markdowns) of 4.0% to 4.5% of sales, whereas the efficient exemplars have losses as low as 2.0% to 2.5%.

Several elements of the operating model merit attention. One is collaboration between retailers and suppliers. Retailers and suppliers can achieve mutually beneficial outcomes by working together to improve promotion planning and on-shelf availability; tailor flows and delivery volumes by format, store, and category; and cut supply chain costs.

Another important element is labor, which accounts for far and away the largest chunk of store operating costs. The key here is to establish and apply standard operating procedures that routinize store execution, improve productivity on the shop floor, and free up associates’ time to spend with customers—all of which helps the bottom line.

There can be no doubt that shoppers’ buying habits and needs have changed substantially in the past decade. Name-brand loyalty is a thing of the past; the targeted assortment retailers have proved that point. It’s time for mainstream stores to grasp those changes, too, and respond appropriately, with long-term positioning in mind.