Yue, a 38-year-old mother in Beijing, knows all about the limitations of health insurance in China. Her public insurance allows her to go to public hospitals to get routine care, but those hospitals are crowded and confusing to navigate. She has often been unhappy with the quality of doctors and the overall experience. Indeed, when her son was suffering from a fever, she decided against taking him to a public hospital and instead brought him to a highly regarded private hospital. After two days, her son’s condition improved. But the private hospital didn’t accept public insurance, and Yue ended up paying RMB 10,000 (

Not long afterwards, Yue bought a supplementary private reimbursement policy. Only about one in 20 people in China owns such a policy, so Yue was doing something out of the ordinary. But as China’s middle-class and wealthy populations grow, tens of millions of people will be turning to reimbursement policies in search of improved care, a more satisfactory experience, and a better chance of ensuring their families’ health.

The growing interest in reimbursement insurance among Chinese consumers is creating an opening for private health insurance companies, both local and foreign, that want to do more business in China. And as private forms of insurance gain a toehold in China’s vast market, others in the ecosystem—including private hospitals—are likewise taking note.

Today, the vast majority of people in China are part of a public insurance system that is inefficient in many ways. The system pushes people to public hospitals for every sort of ailment—and once in a hospital, people often have to endure long waits to meet with a doctor who doesn’t have much time, in a setting that doesn’t offer much privacy. In lieu of individualized care, the default is sometimes to administer drugs or an IV saline solution and see how the patient fares.

There is also widespread dissatisfaction with reimbursement practices. About 50% of individual health care spending in China is out of pocket. So if a family member has a health problem that results in RMB 1,000 in medical bills, the family will pay an average RMB 500 out of pocket. If the cost of treatment is beyond a family’s means, the patient may receive inadequate treatment—or even none at all.

China’s Private Health Insurance Market

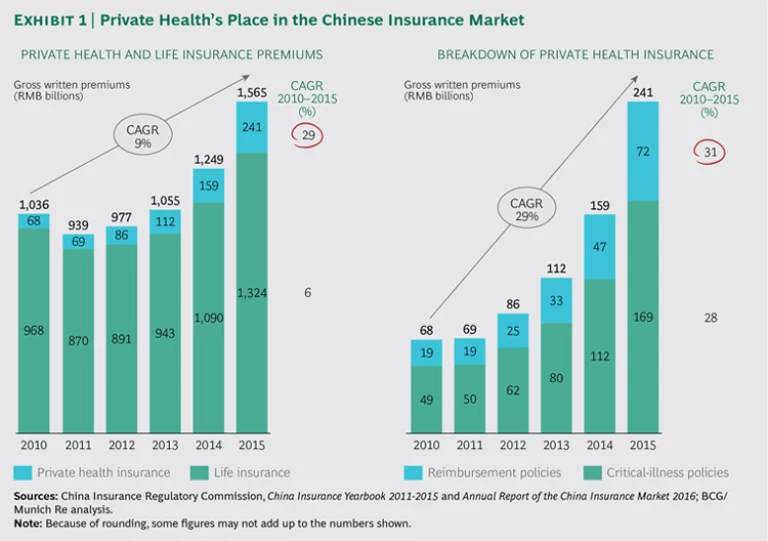

As of 2015, private health insurance in China was about an RMB 241 billion ($36.7 billion) market, having grown rapidly—at about 36% a year—since 2010. The majority of the market consists of critical-illness policies—indemnity products sold by life insurance companies. Such products pay a lump sum if the insured person is diagnosed with any of a set of agreed-upon medical conditions. These policies are usually offered as riders to life insurance products and are easy to sell and design, a fact that has led to their popularity. However, critical-illness policies cover only a narrow set of predefined conditions, such as specific types of cancer. And their structure doesn’t allow for ongoing reimbursements if long-term treatment is needed. To get such coverage, people must have a purer form of reimbursement health insurance that covers them no matter what their diagnosis.

The market for private reimbursement insurance in China is quite small today. Whereas many prominent Chinese life insurance companies offer critical-illness policies, relatively few insurers offer reimbursement insurance. Certainly life insurance is a much more lucrative market than health insurance in China. For every RMB 1 in combined critical-illness and reimbursement premiums sold there, more than RMB 5 in life insurance premiums are sold. (See Exhibit 1.)

There are a number of reasons for the underdevelopment of the reimbursement health market in China, including a lack of consumer awareness about the benefits of such products and a lack of strong sales channels to reach consumers. In addition, because of reimbursement’s limited presence, those selling it haven’t been able to forge strong relationships with hospitals and other entities that might be able to provide data about patients and treatment outcomes. This has made it hard for private health insurers to price or design their products and to manage claims. Partly as a result of this situation, the claim ratios for reimbursement insurance have been both unpredictable and very high. The lack of profitability of pretty much all pure-play Chinese health insurers has discouraged them from developing their reimbursement offerings further and from investing in the area.

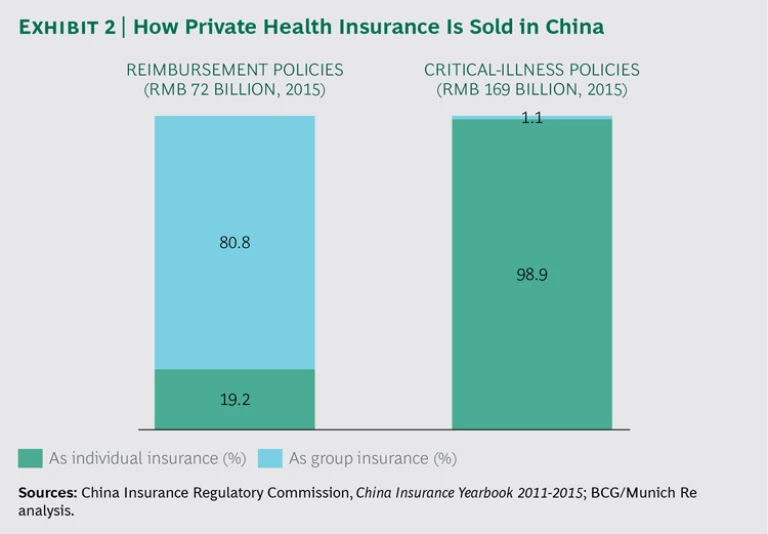

Most people with reimbursement insurance in China have obtained it through group policies at the companies where they work. (See Exhibit 2.) Multinational corporations that do business in China often offer their executives high-end reimbursement policies that cover visits to private hospitals. The reimbursement insurance available to middle managers at these companies tends to be more limited—for instance, covering surgical procedures only at public hospitals. There are also differences according to employers’ financial strength, with the most profitable MNCs typically offering the most generous reimbursement benefits.

While the market for group-provided reimbursement insurance will continue to grow, a lot of the new group business is likely to come from local Chinese companies and small and midsize foreign enterprises (such as private equity firms). Both categories of businesses are adding scale and becoming more profitable in China, and both will look to provide reimbursement insurance on a group basis in order to compete for the best employees.

Why the Reimbursement Market Is Poised to Grow

Despite the obstacles to the use of individual reimbursement insurance in China, the market will grow substantially. Several developments make this a certainty.

The first is a set of new government policies in support of private health care. Chinese policymakers understand the limitations of China’s system of social insurance and have taken steps to encourage consumers to embrace private insurance. These steps include tax breaks for individuals who buy private insurance and moves to encourage partnerships between health insurance companies and private hospitals.

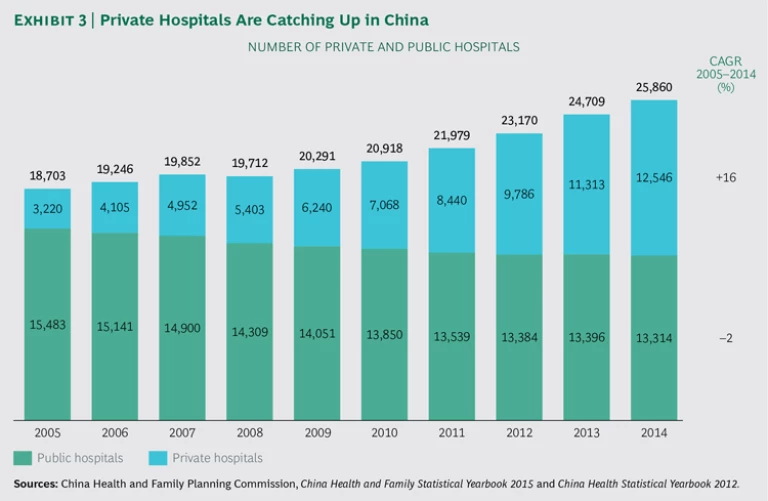

Second, the government has introduced incentives for more private hospitals to form and operate. As of 2005, there were only about 3,200 private hospitals in China. By 2014, that number had almost quadrupled, to more than 12,500. (See Exhibit 3.) A growing ecosystem of private hospitals is critical to the development of reimbursement insurance because private hospitals can share data with insurers and be partners in the push toward a healthier population.

The third and perhaps most important development is the growing sophistication of certain segments of the Chinese population when it comes to reimbursement policies. Like Yue, many middle-class and affluent Chinese have grown frustrated with the public health sector: the difficulty of finding good doctors, the experience of navigating enormous, poorly laid-out hospitals, the long waits to see doctors, and the overreliance on IV therapy. Increasingly, these consumers say they would be willing to pay for private insurance if it provided something better.

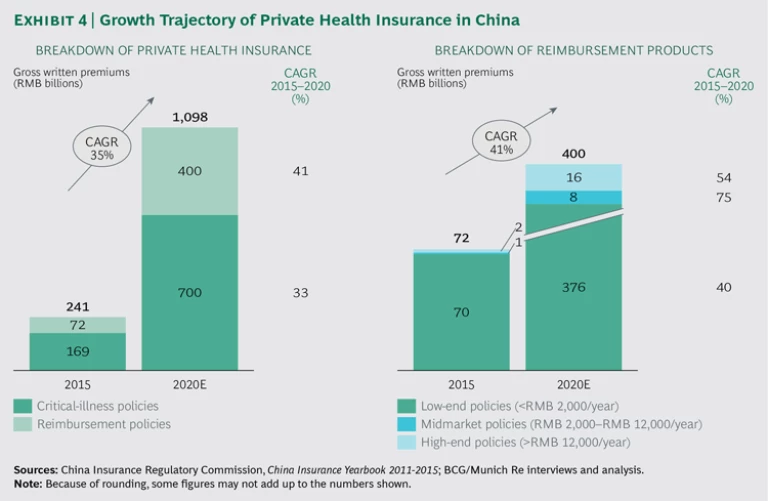

Together, these developments position reimbursement policies purchased by individuals to become a substantially bigger part of the health insurance market in China. Such policies have grown faster than the market for critical-illness policies in recent years. Our expectation is that this trend will continue and that reimbursement products at every level—low end, midmarket, and high end—will enter a sustained period of more rapid adoption.

For instance, the market for low-end reimbursement products, with annual premiums below RMB 2,000 ($300), will grow upwards of 40% per year between now and 2020. There will be even faster growth—likely exceeding 50% a year—in high-end reimbursement products: policies priced above RMB 12,000 ($1,800) annually. The fastest growth will be among midmarket policies—those costing between RMB 2,000 and RMB 12,000. (See Exhibit 4.) From a product perspective, this segment is largely a white space in today’s Chinese reimbursement market.

One risk is that those buying reimbursement insurance on an individual basis will be sicker than average and thus more expensive to insure. Reimbursement insurers need to factor this in as they design and position their products.

Segmenting China’s Health Care Consumers

Several factors drive Chinese consumers to consider reimbursement policies. One is the extent to which they are frustrated with the public health system and are searching for alternatives. New parents, in particular, are likely to find themselves in this position. Having experienced the crowds and long waits at public hospitals, many Chinese want something better for their children. Indeed, the birth of a child is probably the single biggest trigger of private reimbursement purchases in China. Some parents buy private policies just for their children and continue to make do with the public system for themselves.

Besides the birth of a child, age and income are the most important factors determining consumers’ willingness to consider private reimbursement insurance. Next come education level and vocation.

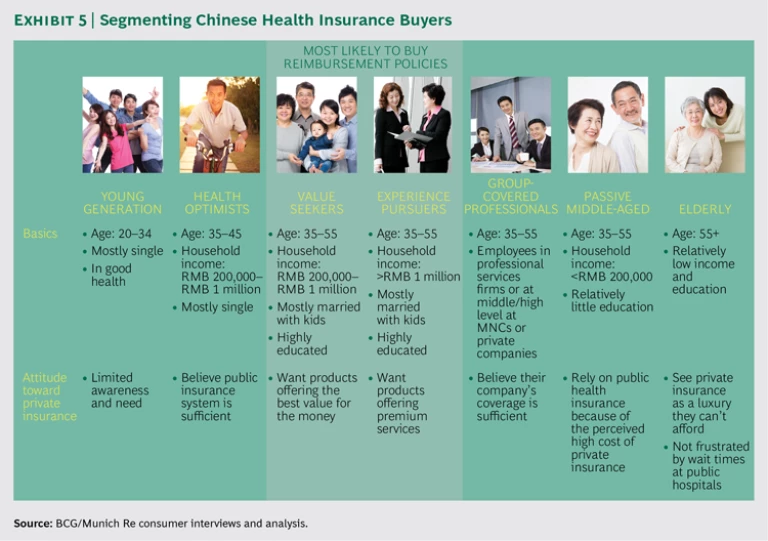

In a survey of almost 1,000 Chinese consumers, BCG and Munich Re identified seven groups of individual health insurance consumers in China, two of which have especially high potential as purchasers of reimbursement insurance. We call the first high-potential group “experience pursuers.” (See Exhibit 5.) These are people aged 35 to 55 with household incomes above RMB 1 million ($152,000). By our calculation, there will be more than 4 million such people in China by 2020. Highly educated and typically married with children—and

The second high-potential group comprises consumers who are likewise aged 35 to 55, usually married with children, and highly educated; we call them “value seekers.” With household incomes from RMB 200,000 to RMB 1 million, they are somewhat more cost-conscious than experience pursuers and would probably be willing to pay between RMB 12,000 and RMB 15,000 annually ($1,800 to $2,300) for a policy covering a family of three. We expect about 38 million Chinese to fall into this category by 2020. Value seekers don’t mind public hospitals as long as their insurance gives them access to the VIP section (where the waits are typically shorter and the doctors less harried). Value seekers can be broken down into two subsegments: a mid-low-end group willing to pay RMB 2,000 to RMB 6,000 ($300 to $900) annually for an individual policy and a mid-high-end segment willing to pay RMB 6,000 to RMB 12,000 ($900 to $1,800). The first group is looking for risk protection, pure and simple; the second is looking for services on top of risk protection, including broad coverage for diseases and drugs.

To date, neither experience pursuers nor value seekers are buying reimbursement insurance in large numbers. This is partly an awareness issue: consumers in these segments barely know that reimbursement insurance exists, let alone the benefits it provides. The information problem came through loud and clear in a set of interviews we did with consumers. “I have friends who are interested in private insurance but have no idea where to get it,” said a financial executive in Shanghai who has group reimbursement insurance. Another Shanghai resident, not quite as wealthy as the first, said she had been frustrated in her attempts to get information directly from insurance providers and ultimately relied on the recommendation of a friend in deciding which private insurance to buy. “The information on the websites of the providers I looked at just wasn’t thorough,” she said. “I couldn’t understand what they were offering.”

The lack of health insurance purchasing by these two high-potential groups may also reflect poor product design. In the course of our field interviews, we heard complaints about needlessly high or excessively low maximum reimbursements for outpatient procedures, unused second-opinion physician hotlines, and unnecessary coverage for treatment in foreign countries. Poor product design isn’t a problem unique to health insurance in China; it happens in every industry all over the world. And the result is always the same: when a product doesn’t match consumers’ needs, they don’t buy it.

Finding Success in China’s Reimbursement Insurance Market

The questions for companies looking to establish an early lead in China’s nascent reimbursement market are how to get their wealthy and middle-class prospects to buy a policy and how to operate profitably. We believe that six capabilities will be essential. Private health insurers that develop or deepen these capabilities will be able to attract more business from individual consumers. Just as important, they will position themselves to turn reimbursement insurance into a profitable area of activity.

Advanced Customer Segmentation. Insurance companies need to understand the characteristics and preferences of different customer segments: the amount of money they are willing to spend on reimbursement insurance, what they expect to get in return, the essential (versus nice-to-have) product features they are looking for, and the marketing or sales approach that works best for them.

For instance, there’s a clear preference among experience pursuers for recommendations from family members or friends. Therefore it might be fruitful to try to penetrate this high-end segment’s social network in order to elicit word-of-mouth recommendations. Also, these consumers’ demand for a generally better medical experience suggests that insurers should invest in building premium hospital networks and improving end-to-end services. Similarly, the preference of value seekers for online research means that insurers trying to reach them should look for ways to use online and social media in their marketing.

Expertise in analytics and a strong data infrastructure are essential to advanced customer segmentation. Such expertise can help with traditional applications—using consumer research to make customer interactions more straightforward—and enable highly innovative applications as well. For instance, some insurance companies in the West have considered using social media postings as the basis for predictive modeling in order to identify consumers’ otherwise unknown risks. Privacy concerns have kept such approaches from moving into general use, but it seems inevitable that new sources of consumer data and the ability to analyze them will become increasingly important to insurers in the future.

Differentiated Proposition and Product Design. Once insurers understand the needs of a target segment, they must create products that will meet those needs. This kind of innovation—developing a new product type or significant new features—is still quite rare in China. An insurer that becomes adept at it will have a big advantage.

Differentiation could take a variety of forms. For instance, an insurer could structure a reimbursement product for consumers active in or interested in sports and then subsidize sports club memberships as a way of marketing it. Or it could create reimbursement products associated with specific pathologies, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease. An example is the way in which Barmer GEK and DAK-Gesundheit (two German “sickness funds”) have gone about lowering the cost of treating osteoporosis in Germany. After aggregating patient data from multiple regions, they used sophisticated analytics to identify the most cost-effective way of treating this debilitating condition, which accounts for more than $7 billion in health care spending in Germany each year. The data ultimately persuaded the two funds to cover an innovative new drug, despite its high upfront costs.

Since consumer data is limited in China, this means of making decisions about drug coverage would probably not be available to Chinese insurers. But there may be other ways to obtain the data needed for condition-specific insurance products, such as partnerships with pharmaceutical companies.

Channel Development. Chinese health insurers generally don’t have effective channels for reaching consumers of individual insurance products. As the interviews we did in China’s tier 1 cities made clear, the problems start with insurers’ websites, which frequently fail to provide the necessary information. Correcting this should be among the first digital investments that insurers make.

There are many more advanced ways to use the digital channel to market to consumers. PingAn Insurance, for instance, has introduced an online platform called Good Doctor that connects patients with a network of 50,000 contracted doctors and specialists. Good Doctor offers round-the-clock medical consultations via text and video, using an appointment feature. Besides offering an alternative to long hospital wait times, the application has considerable potential as a customer acquisition tool. Some 77 million people have registered to use Good Doctor and hundreds of thousands of health queries are made over the system daily. People using the app can also get information about PingAn’s medical insurance plans.

Offline channels, too, are crucial. Although this is starting to change in select markets, reimbursement insurance is for the most part still sold by intermediaries. It is thus imperative for private health insurers to invest in their agent and broker networks. Wealth management advisors at banks are one potential sales channel, given their experience explaining complex products to well-to-do clients.

The online and offline channels can also be integrated. This is what the German insurer Allianz has done, using Facebook as a platform for its agents. Agents offer advice and services on their own Allianz-branded Facebook pages, allowing them to communicate with existing and prospective customers in a consistent setting.

Efficient Claims and Operations Management. Piquing the interest of consumers—and even getting them to buy reimbursement insurance—won’t count for much if a company can’t make a profit on these policies. Operational efficiency can lower an insurer’s costs. For example, PingAn has built an IT system that takes into account hospital type, hospital location, and claim amount in order to identify potentially fraudulent claims.

Efficiency can serve twin goals, increasing customer satisfaction at the same time that it helps insurers become more profitable. Claim Connect, a mobile app launched by Aviva in Singapore in 2015, allows users to scan or take photos of their medical claims and submit them electronically; they can also check the status of current claims or view their claims history. Some 140 Singaporean companies have introduced Claim Connect to their employees, who now submit more than half their claims through the app. That has reduced the amount of time that Aviva spends on paperwork. It has also meant faster turnaround of claims and earlier availability of information about claim status—two clear customer benefits.

Hospital and Health Provider Network-Building. Until now, private insurers’ weak ties to major public hospitals have kept them from getting the patient data that would help them price and design successful products. Similarly, their limited involvement with physician groups has prevented them from instituting practices that would allow them to lower their risks and claim ratios.

But now that regulators are allowing insurers to invest in hospitals, these obstacles are no longer inevitable. And some Chinese insurers are moving to capitalize on their new freedom. Sunshine Insurance was one of the first, building a 2,000-bed hospital in Weifang in cooperation with the government. The hospital, called Sunshine Union, opened for business in May 2016. Taikang Life, another insurer, is investing billions of renminbi to build a network of hospitals, elder-care communities, and specialty facilities—not unlike Kaiser Permanente’s model of managed care in the US. In some cases, Taikang is building hospitals from the ground up; in others, it is buying public facilities and privatizing them.

There are twists on the theme of network development that could work in China. For instance, a Chinese insurer could create a network of nursing care facilities for the elderly, as Sompo Japan Nipponkoa, one of Japan’s largest insurers, has done in that country. Sompo owns almost 500 nursing homes in Japan and has 400 offices providing at-home services. Such a network makes perfect sense in Japan, which has one of the world’s largest populations of people aged 65 and older. But it could also make sense in China as the country’s population continues to age.

Partnerships with health providers are another way to add customers and to control risks. This is what China Taiping has done through its relationship with Arrail Dental. In return for marketing Arrail’s services, Taiping has gained immediate access to 30 clinics in seven tier 1 cities in China. In addition to providing Taiping with deep discounts, the arrangement gives the insurer valuable information about the costs and risks of dental care. This will allow it maximize its profitability in this lucrative area of health care.

Health Management. This capability involves the use of wellness programs—incentives to exercise, lose weight, and stop smoking, among other things. In Hong Kong, the insurance company AIA encourages policyholders to complete online health assessments and get regular checkups through its Vitality product; AIA Vitality also lets them track their exercise and sleep patterns. Policyholders with good health habits earn such benefits as gift coupons and discounts at retail shops and movie theaters. The data that AIA collects allows it to improve pricing, anticipate claims, and encourage at-risk customers to adopt healthier habits.

A program that helps prevent illness, rather than just providing treatment after the fact, is obviously best for a health insurer. But wellness programs are also helpful for patients struggling with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension.

In the US, many insurers are paying for telemonitoring programs that take a proactive approach to treating heart disease. Clinical data is captured at home and transmitted to the patient’s doctor, who can spot changes that may signal trouble. According to Priority Health, a Michigan insurer, participants in its telemonitoring program have fewer emergency room visits and hospital admissions, and shorter hospital stays, compared with participants who are not telemonitored. At the same time, insurers are pushing chronically ill patients toward apps and devices that remind them to take their prescription medications.

The key to successful health management is simplicity. The more integrated into a patient’s daily life the regimen is, the more effective it will be. This is true all over the world, and it will also be true in China.

Conditions have never been more favorable than they are today for reimbursement insurance to become a prominent part of China’s health landscape. To be sure, there still aren’t enough well-designed offerings, nor do many Chinese know what private health insurance is or where to get it. But widespread dissatisfaction with the system of public insurance, the Chinese government’s encouragement of alternatives, and the growing number of Chinese who can afford to pay for more than what they get from the public system will fuel substantial growth in the next few years.

The winners in this fast-developing part of the health care market will be those that move the soonest and operate from a strong base of knowledge. This means rolling out the right products and services at the right time over the next few years. The returns from doing so are potentially huge.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Wenxin Deng and Yanmei Shi of BCG and Vivienne Dong of Munich Re. They also thank Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Carrie Forster, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, Gina Goldstein, Robert Hertzberg, and Sara Strassenreiter for writing, editing, design, and production.