When Chinese life and auto insurers set their agendas, they should think about how to make their brands more trustworthy, their products and services simpler, and their claims processing faster and more transparent. These attributes matter most to Chinese consumers and are fast becoming prerequisites to success for providers.

These are among the findings of a survey of 3,200 Chinese consumers that was conducted by The Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight. Participants were asked whether they had recommended or criticized a life or auto insurance provider within the most recent 12 months, and if so, why. Their answers provide a map of where insurers can look to gain an advantage.

The Chinese insurance market is changing rapidly. In buying insurance, people have more choices than ever before—now that the government has opened the market to more companies—including foreign competitors. Furthermore, regulators have been pushing insurers to offer flexible premiums in addition to the fixed-price premiums that prevailed in the past. China’s Internet-plus action plan is adding to the pressure on insurers to make their services available through multiple channels and devices. That pressure is coming also from consumers, who are changing their behavior as they increasingly handle their personal affairs on mobile devices and with e-commerce companies.

The net effect of these developments has been to shift power from providers to consumers and to increase the importance of customer experience as the key factor that will determine which insurance companies will prevail.

The Importance of a Trustworthy Brand

By far the biggest reason for recommending a life insurance brand, the survey shows, is the brand’s perceived trustworthiness, which manifests itself in advice that consumers consider has been tailored to meet their personal needs and in recommendations that are unbiased. Simplicity—insurance products and processes that are easily understood—is the next-most-important attribute. Trustworthiness and simplicity are also the attributes that trigger the most recommendations of auto insurance brands.

Simplicity is central to the experience that customers want at every stage of the insurance process—research, purchase, post-sales services, claims, and renewal. Trustworthiness and one other factor, word of mouth, are highly important in the research stage, but during the purchase stage, neither is as important as product attractiveness—namely, the affordability of the premiums. After the insurance has been purchased, other drivers of recommendations come into play, such as convenience and, especially, customer service.

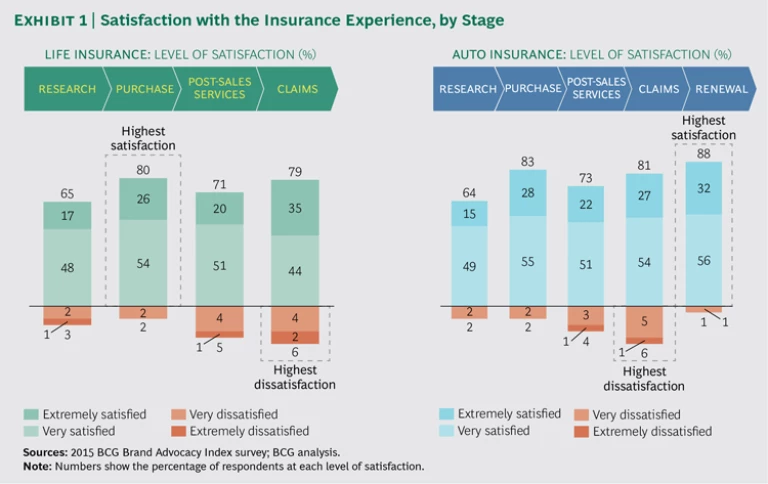

The claims stage, which generates the most dissatisfaction, is an area in which Chinese insurers might consider differentiating themselves. (See Exhibit 1.) Half or more of those who had criticized an insurance brand within the preceeding 12 months said that they had done so because of a frustrating claims process that is too slow, is not transparent enough, falls short of the customer’s payout expectations, or requires too much effort from the customer. More than one in five said that the level of service they received during the claims process wasn’t the same as the level they had received earlier.

Lack of transparency (an issue related to customer service because it reflects a customer’s or a prospective customer’s inability to find information) is another big source of criticism. Of those who criticized a life insurance brand, 15% said that they have a hard time understanding what is needed to complete an application in the first place.

For both life and auto insurance, customer service issues gain importance as customers advance through life stages. For instance, customer service is the biggest concern for

Older respondents (independent of their life-stage situations) are also more apt to say something negative about an insurance brand when they feel they’ve been given poor customer service. Whereas 18- to 25-year-olds are most likely to criticize an insurance brand for an inherent aspect of the product or for word-of-mouth reasons—in effect repeating a criticism that they’ve heard from friends or family members—older customers are more likely to cite service issues as their reason for criticizing an issurer. Among people aged 46 to 55, for instance, more than three in five customers who had said something negative about their life-insurance provider in the previous 12 months—to a friend, to a family member, or in a social-media posting—did so after a poor customer-service experience. Nothing else accounted for anything close to that level of expressed dissatisfaction.

Finding Consumers Willing to Become Advocates

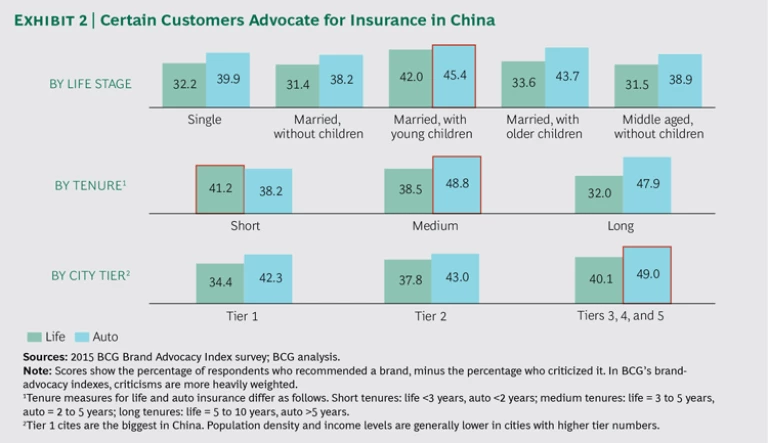

On the flip side, consumers in some cohorts tend to speak more favorably of insurers. In life insurance, married couples with young children have a brand advocacy score of 42, at least 8 points higher than those in the life stage with the next-highest score. (See Exhibit 2.) The difference is narrower in auto insurance, but even in that category, married couples with young children have the highest advocacy scores. (See “Survey Methodology: How the Brand Advocacy Data Was Gathered.” )

Survey Methodology: How the Brand Advocacy Data Was Gathered

Here is some information about the research underlying this article.

Survey Date. 2015.

Sample. 3,200 Chinese consumers.

Method. The survey was conducted online. Those participating were asked what they had said about a brand—to friends, to family, or on social media—within the preceding 12 months.

Participants’ Profile. Of the respondents, 77% were college graduates. More than three-quarters lived in tier 1 or tier 2 cities, and two-thirds had monthly incomes greater than RMB 12,000, qualifying them as upper-middle class or affluent.

Scoring. In BCG’s scoring system, spontaneous advocates are seen as more valuable than nonspontaneous advocates, who recommend only in response to a question. The recommendations of spontaneous advocates get twice as much weight as those of the nonspontaneous. The most weight is given to comments of spontaneous critics because of the damage their criticism can do to a brand. The calculation for brand advocacy treats one spontaneous criticism as the equivalent of two spontaneous recommendations.

The higher advocacy scores may stem from the greater attention paid to insurance by people at this life stage. Those in the married-with-young-children group have more reasons to own insurance than those in other groups. They have more life insurance than the average Chinese insurance customer (1.9 products compared with the average 1.7) and, on average, spend about 15% more on life insurance products (RMB 7,773 compared with the average RMB 6,732). In auto insurance, there is less difference between the number of policies owned by married couples with children and the number owned by other groups, and less difference in the amount spent across groups on those policies.

A combination of factors affects brand advocacy as customer tenure increases. On the life insurance side, customers are most apt to recommend their providers during the first five years in which they own life insurance; brand advocacy drops off between years five and ten of ownership and declines further after the tenth year. This is almost certainly because of the number of interactions between life insurers and customers when the relationship is new and the more sporadic nature of those interactions as the years go by.

By contrast, customers’ brand advocacy for auto insurance is at its lowest in the first two years after purchasing a policy. In their first year of owning a car, a lot of Chinese use an insurance product that the automobile dealer has bundled in as a condition of selling the car at a discount. Consumers’ freedom to explore other insurance options after the first year may allow them to find insurers more to their liking.

The truism that those who live in big cities are harder to please holds for Chinese insurance customers. Both auto and life insurance providers have more brand advocates in tier 3, tier 4, and tier 5 cities (which have smaller populations and less competitive insurance markets) than in tier 1 cities such as Beijing and Shanghai.

One of the surprises of the survey results is that advocacy scores for auto insurers are higher than those for life insurers. Automobile accidents are among life’s inevitable frustrations, and even when they are minor, the aftermath—filing a claim and collecting payment—is often tedious, time-consuming, and expensive. Yet, during most interaction stages—claims included—auto insurance customers express more satisfaction with their providers than do life insurance customers, and auto insurers have higher overall brand-advocacy scores (44.3 versus 36.8 for life insurers).

Greater Trust in Big Insurers

In China, “big” is sometimes equated with “reliable,” so it’s no surprise that big insurers have the highest brand-advocacy scores. Many of the recommendations that big insurers elicit stem from their perceived trustworthiness and the simplicity of their propositions. From a stage-of-insurance perspective, a higher percentage of customers of big insurance companies than of small insurance companies also said that they are satisfied with what happens at the research stage. The area most in need of attention among big insurers in China seems to be their product offerings themselves, which in some cases are less attractive to consumers than the offerings of smaller insurers.

Smaller insurance companies in China generally have lower brand-advocacy scores than big insurers. This is due, in part, to the smaller companies’ lacking the same brand recognition as larger insurers and being less likely to be considered by people making a switch. However, when it comes to transparency and product attractiveness, small insurers have relatively high brand-advocacy scores—equal to and sometimes exceeding those of big insurers—as well as the flexibility to offer customized products.

Small and midsize insurers may be able to use these attributes to their advantage, especially in China’s underserved niche insurance markets.

Insurers’ Future Moves

As China’s life and auto insurance industries mature and competition intensifies, there will be changes. Chinese consumers will become more sophisticated about insurance, making them harder to please (a challenge already seen among the more demanding Chinese living in tier 1 cities). In life insurance, the marked falloff in advocacy that happens the longer a customer stays with a given provider could translate into defections. If smaller providers offer more flexible, more affordable products along with a more convenient experience rooted in technology, they will have a good chance to pick up share.

Insurers will have to adapt in this evolving environment. For many Chinese insurance companies, a focus on improving the customer experience will mean exploring new distribution models and moving away from an outmoded one-size-fits-all sales approach. It will mean shifting the culture and KPIs to focus on customers rather than on economic factors only. And it will mean devising a true omnichannel strategy that allows customers to interact with their insurance providers through an app on their smartphones, for instance, as well as offline.

Amid these shifts, it will be important for Chinese insurers to gain a clearer understanding of how consumers view their brands. If it’s true that consumers vote with their wallets, either renewing policies or not, it’s also true that they vote with their voices—in casual commentary they make every month, every week, and even every day.

Knowing which customers are unhappy enough to complain to a friend or family member (and understanding why) can give insurers a chance to reinforce essential attributes before those attributes undermine the business. Likewise, knowing which customers are happy enough to make word-of-mouth recommendations can be an important ingredient in an insurer’s marketing strategy and growth plan.

In the immediate future, the no-regret moves for Chinese insurers will be to enhance their trustworthiness, offer simpler and more transparent products and services, and improve their claims processing. Chinese insurers don’t have to rely on gut instinct to recognize the importance of such changes. Their customers are telling them what matters loudly and clearly.