A digital revolution is putting more than half a trillion dollars into play. Television and filmed entertainment, especially traditional broadcast TV, is being transformed by the big and fast-growing inroads of internet and over-the-top (OTT) video platforms. Some $570 billion in annual market value—in content creation, aggregation, and distribution—is at stake.

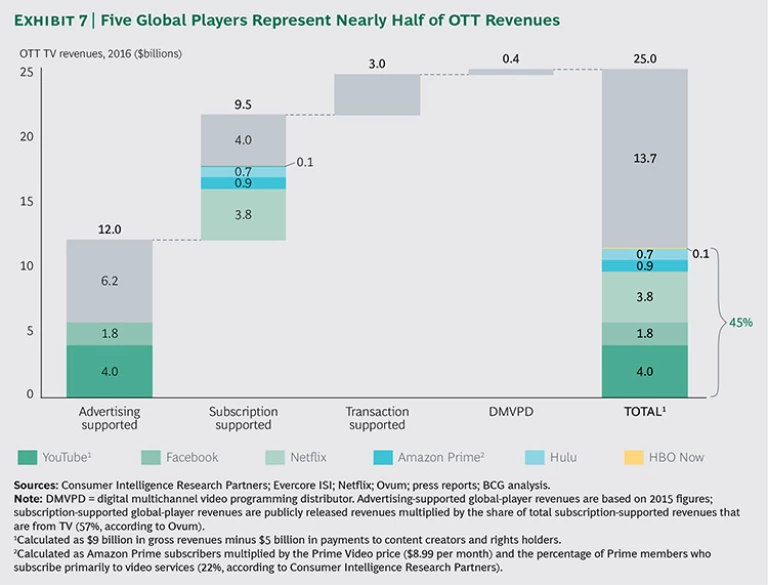

OTT television—representing some $25 billion in annual revenues worldwide and generated mostly by a handful of big US-based global players, including Netflix, Amazon, and Google’s YouTube—is at the center of this revolution. Its impact on traditional networks (broadcast and pay TV) and video distributors (cable, telco, and satellite) has been extensively examined. To date, however, there has been little study of the impact of OTT and the changing TV landscape on the various domestic production ecosystems around the world.

OTT in the Context of the TV Industry

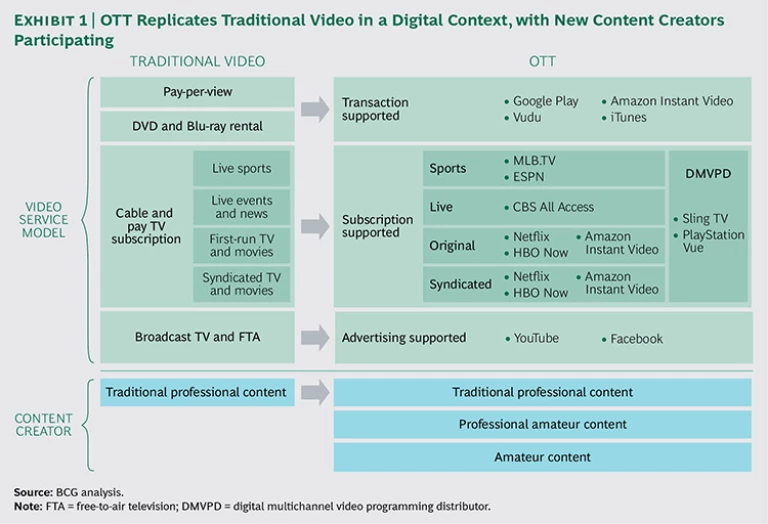

OTT encompasses the distribution of video content “over the top” of traditional distribution technologies. At the most basic level, OTT is simply a technology alternative that allows for the replication of the traditional home entertainment “stack” of consumer value propositions in a digital context. In technology terms, OTT is the delivery of video content through fixed or mobile broadband internet connections instead of over the broadcast TV spectrum or dedicated cable, fiber, or satellite networks. In many ways, OTT is neither more nor less than a replication of the traditional set of consumer video services.

Furthermore, although OTT mirrors the traditional video stack, digital technologies enable many distinctive characteristics and features that are not possible with over-the-air, cable, or satellite distribution. These include the sheer breadth of content available, flexibility of time and place for viewing content, and the flexibility of consumer offerings and price points that companies can offer and from which consumers can choose.

Finally, OTT and traditional TV are further differentiated by the content creators that participate in the space. By eliminating constraints on content distribution and space, OTT has introduced new types of content creators to the market. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Traditional professionals produce expensive, high-quality content and are characterized by a well-defined and well-funded ecosystem of studios, production houses, and professional talent (including actors and directors). Before OTT, this group constituted the TV content production ecosystem.

- Professional amateurs (pro-ams) do not have access to large production infrastructure, but they have regular production schedules and profit motives, and they generate revenues. They are focused primarily on producing content for OTT, and many began as amateurs on YouTube or other social media platforms (for example, The Young Turks).

- Amateurs make content sporadically, but they are frequent and prolific contributors to the content community. Their output forms the backbone of consumption on social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat. Amateurs are especially good at capturing the viewing public’s imagination: many amateur videos have “gone viral” and been seen by millions. This is a completely new but hugely important part of the content production ecosystem.

A $25 Billion Industry in 2016

These alternatives have been welcomed by consumers, who today enjoy significant choices beyond the traditional pay TV and broadcast ecosystem. As a result, in just a few years, the OTT TV video category has grown to $25 billion in annual revenues. Although this represents only some 5% of the global industry, OTT is growing by more than 20% annually and winning share over traditional TV, whose revenues are growing at a far more subdued rate of 2%.

However, simple market statistics under-emphasize the impact of OTT, which has been a driving force for change in the wider video industry. OTT’s impact encompasses how consumers interact with content; what they expect in terms of choice, flexibility, and navigation; and the competitive context in which incumbents and upstarts now operate across the value chain.

We have extensively detailed the history of these changes and the technology advances that have enabled them. (See The Value of Content , BCG report published with Liberty Global, March 2016.) However, in order to address the fundamental focus of this study—the impact of OTT on global and individual countries’ domestic content production—it is important to assess the current state and likely future direction of OTT’s impact at both the global and the domestic level. In this chapter, we examine the OTT market, the changes in consumer behavior, and the players and player types that are the driving market forces in content production. We also address several misconceptions. For example, it is the view of some that OTT has benefited only the US content production ecosystem, to the detriment of domestic players in other countries. Before that conclusion can be confirmed, it’s necessary to weigh the degree to which OTT has unlocked global audiences’ access to locally produced content—across genres and across the spectrum of traditional professional, pro-am, and amateur participants.

Player Types and Value Pools of Professionally Produced Content

In the past, the online value chain has included three primary video-on-demand (VOD) business models, known as AVOD (advertising-based VOD), TVOD (transaction-based VOD), and SVOD (subscription-based VOD). As the VOD abbreviation indicates, these services are not tied to a linear television schedule in which the TV company sets the time of viewing. However, there are an emerging number of OTT players that now offer live content but are not tethered to traditional, facilities-based distribution infrastructure such as cable or telco. For example, Facebook Live, which is supported by advertising revenues, streams video content.

Consequently, the traditional VOD moniker no longer wholly applies. The OTT market is better defined now by the following four player types, each of which competes in—and is disrupting—a value pool within the traditional home video stack of services: advertising-supported services, transaction-supported services, subscription-supported services, and digital multichannel video programming distributors (DMVPDs).

Advertising-Supported Services. These services offer free access to large libraries of movies, TV shows, clips, and other live or on-demand content from professional as well as amateur content creators. As with traditional free-to-air (FTA) TV, content and other costs are offset by advertising revenues. Advertising-supported services vary in content type and strategy and include traditional professionally produced content (previously available only through traditional television distribution) and digital-first content from a wide range of traditional professional, pro-am, and amateur players. Advertising expenditures, a fixed pool of dollars whose size correlates closely with the macroeconomic environment, are shifting to OTT video at the expense of print spending and, to a lesser degree, TV ad spending. Germany-based MyVideo and US pioneer Hulu are ad-supported services.

Transaction-Supported Services. Content from these services is available to own or rent for a one-time fee. Video is streamed or downloaded and can be stored on the user’s own hardware and viewed at any time, when, for example, an internet connection may not be available. Transaction-supported players, which offer digital rentals and purchases of primarily professional, long-form video content (TV and films), participate in the home video value pool. And, in fact, there is a nearly one-to-one relationship between the decline in brick-and-mortar home video revenues and the rise of OTT transaction-supported revenues. Apple’s iTunes Store, the Maxdome store in Germany, and Amazon Instant Video are transaction-based services.

Subscription-Supported Services. For a monthly fee, services in this group offer access to a library of content, which typically includes a mix of movies and TV shows. Video is usually distributed via streaming, which requires an active online connection. Subscription-supported entertainment services, such as Netflix and Hulu Plus, and sports programmers, such as MLB.TV in the US and Viaplay in Scandinavia, are competing primarily for consumer spending with subscription TV services. In some cases, these services are also supported by advertising. They focus on the hyperengaged audiences that have, in the past, been the bread and butter of strong cable network brands that dominate a specific content genre. (In the US, these include the cable channels ESPN for sports and Food Network for cooking.)

Digital Multichannel Video Programming Distributors. DMVPDs are also subscription services, but they follow a different model: they seek to replicate the traditional cable bundle in a digital context, essentially bundling and selling online a set of live and on-demand services at a price point that is relatively similar to that of cable and satellite TV companies. And indeed, many of the players are traditional pay TV video companies. Satellite operator Dish Network’s Sling TV is the largest such service in the US. Like transactional players, they replicate an existing content offering and business model, albeit with more flexibility and options for personalization than traditional pay TV. Over time, we believe that share will shift from traditional pay TV bundles to DMVPDs.

The Most Disruptive OTT Services

Transaction-supported and DMVPD services have, so far, had a muted impact on the content creation industry. They remain, in many ways, digital distribution vehicles for existing video content packages at similar price points.

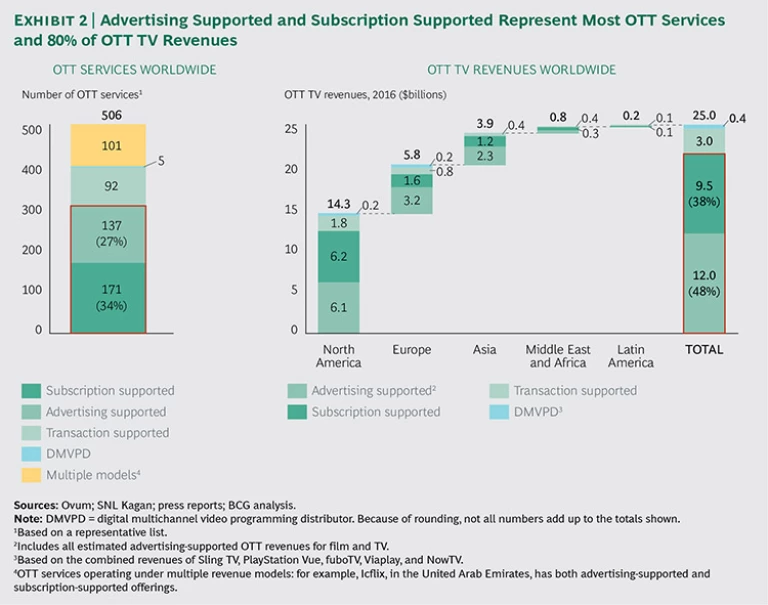

Advertising- and subscription-supported services have, however, materially disrupted the industry with new content models (such as short-form and original content), “windowing” (new approaches to content release), and innovative pricing and value chain relationships (such as Amazon Prime, which, for a set annual fee, bundles high-quality video content with free product shipping). Of the more than 500 OTT services available globally, the vast majority operate advertising- and subscription-supported business models. These players have captured more than 80% of global OTT revenues. (See Exhibit 2.)

How OTT Is Changing the Fundamentals of Content Creation and Consumption

OTT has unlocked three transformational changes in video content and how it is created and consumed: space shifting, place shifting, and time shifting.

Space Shifting. Perhaps the change with the biggest impact on the video value chain has been that facilities-based distribution (such as cable and satellite) is no longer the only means of access for consumers. The music industry provides an instructive example. Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, offers approximately 60,000 music tracks for purchase at its brick-and-mortar locations. Its selection is limited by the size of its stores, a circumstance not unlike the constraint of channels in traditional facilities-based video distribution. In contrast, digital music subscription services, such as Spotify and iTunes, have unlimited “shelf space” and can make some 30 million tracks available to customers.

OTT has had a similar impact in video. No longer are content creators and aggregators bound by the limited-distribution “bandwidth” available on a fixed (even if large) number of TV channels delivered over the air or on cable, fiber, or satellite transponders. It now seems arcane to imagine a world in which facilities-based content distribution—domestic or global—is an asset of significant value. Distribution is no longer a zero-sum game. In all kinds of markets, the internet has eliminated the constraint of shelf space. Almost every video producer or storyteller—essentially anyone with a high-speed mobile or internet connection—now has access to billions of potential viewers, including more than 75% of the EU population and 90% of the US population.

The availability of unlimited content space has altered the definition of the content creator. Far more players—professional, pro-am, and amateur creators—today compete for attention (and money).

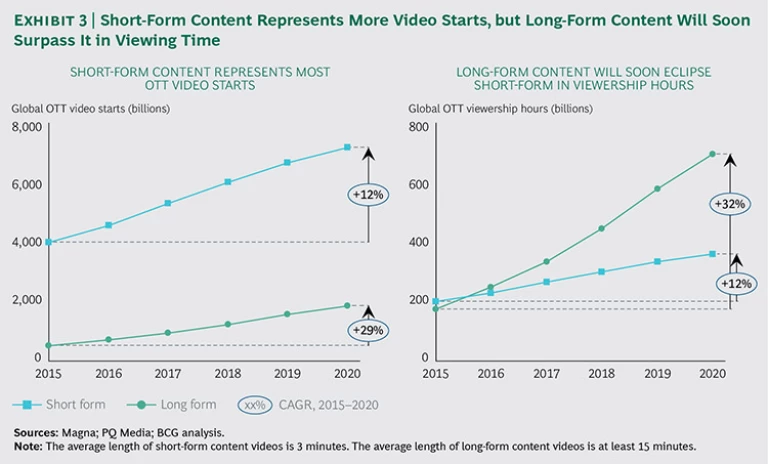

All three types of content creators have been fueling the massive growth in OTT. Pro-am and amateur players are primarily short-form creators, and they are driving much of the out-of-home growth in video consumption, especially mobile short-form video “starts,” or the number of videos that consumers watch. Traditional professional OTT content, which is primarily long form, is taking up a growing share of consumers’ viewing time and cannibalizing more of the at-home viewing experience. (See Exhibit 3.)

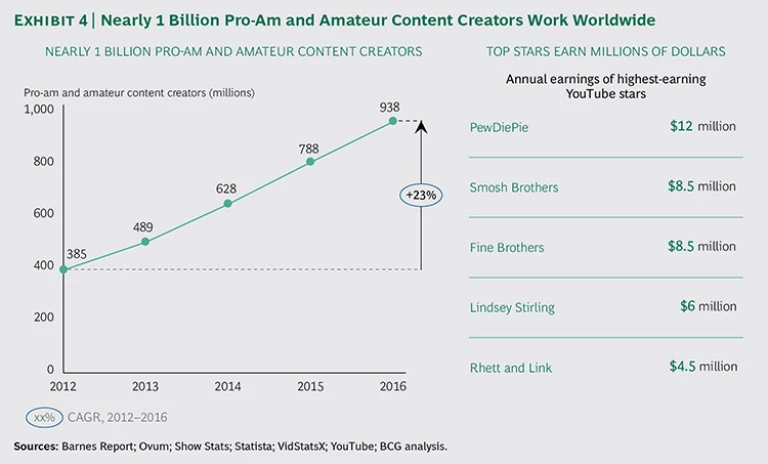

This democratization of consumer access has provided audiences for all kinds of content creators. What many have perhaps failed to recognize is that there are now 1 billion content creators around the world. And although most are amateurs, participating in it as a hobby rather than as a profession, some amateurs are earning millions of dollars, and all are contributing to the depth and breadth of content available to consumers. In the study of the impact of OTT and internet video on content production, one must consider the full range of content producers, not only the professional enterprises that serve the legacy TV ecosystem. (See Exhibit 4.)

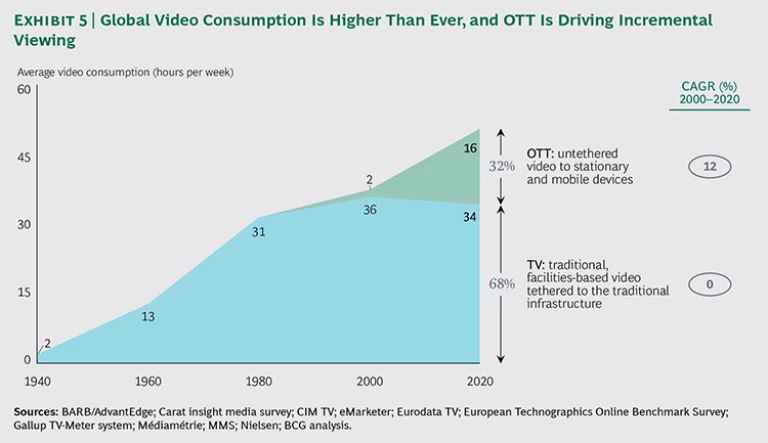

Place Shifting. The proliferation of mobile and streaming access (as well as portable media devices with ever-larger and higher-definition screens) has enhanced consumers’ ability to choose what they watch (scheduled programming versus streaming video) and when and where they watch it (at home or on the go). For example, Facebook says that 90% of its daily active users access the platform through mobile devices. Viewing statistics tell the story: since 2009, overall viewership in the US is up by three hours per week, and almost all of the increase is viewing that is not tethered to traditional facilities-based TV. And although this trend was initially centered in the US, it has spread around the world. Indeed, by 2020, online viewing will account for more than 30% of all video consumption—some 16 hours per week for the average viewer, who, in the early years of this century, watched only a couple of hours of video each week. Online viewing has increased the size of the overall video pie rather than cannibalizing it and has created new consumption opportunities for video viewing both at home and away from home. (See Exhibit 5.)

The increase in mobile-device use as do-everything tools has also changed the type of content that consumers care about. Watching video on a mobile phone—at home or on the go—cannot be the same kind of long-form viewing experience as watching on a big-screen TV. And while long-form video remains very healthy, the rise in mobile use has driven significant demand for short-form, high-quality content that simply didn’t exist before. It bears repeating that this content adds to the overall volume: by and large, it does not replace long-form viewing.

The advent of so-called snackable content has brought major new players to content creation. The Young Turks, for example, offers short-form news videos—many not even ten minutes long—every day on important topics around the world and has become a key news destination for millennials. New digital studios, such as RocketJump, have emerged with a mandate to make short-form, digital-first content. All kinds of consumers are increasingly turning to live, user-generated video and “citizen journalists” for news related to developing events or stories. Yesteryear’s evening news broadcast has nowhere near the same size audience or widespread social impact it once had. (In the US, network news audiences are close to half of what they were in the 1990s.) Public and political events are shaped in real time by video on social media recorded and watched on smartphones.

Large incumbent digital players are also starting to produce more live, snackable content. Facebook Live was launched in April 2016 with the goal, according to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, of making “it easier to create, share, and discover live videos. Live is like having a TV camera in your pocket. Anyone with a phone now has the power to broadcast to anyone in the world.” One media production and casting executive said, “Live video will continue to play an important role and AVOD has the ability to surpass linear because it can broadcast free, live content in a focused way.” Global subscription players, who in the past competed only in long-form content, have also indicated a shift in this direction. In 2014, Amazon rolled out its Video Shorts section, which is dedicated to short-form video. According to another digital-media-industry executive, “Emerging, digital-first content production companies have begun to sell more to OTT players like YouTube Red and Facebook.”

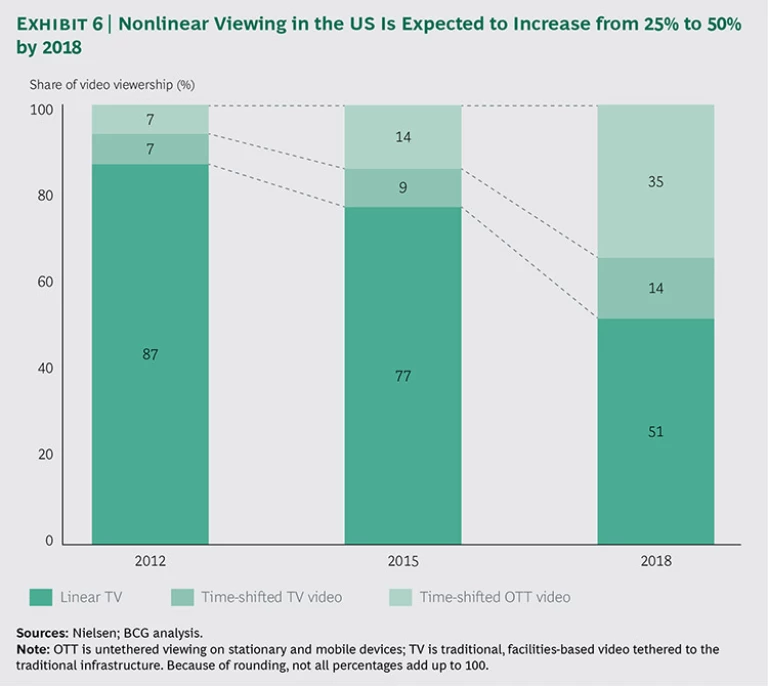

Time Shifting. The combination of the shift in viewing to OTT, which caters to an on-demand content experience, and distributors’ development of “free” VOD services, has moved consumers away from linear “appointment viewing.” Today, nearly a quarter of all viewing hours is nonlinear or time-shifted viewing, either tethered or untethered to traditional facilities-based distribution. The US is ahead in this: by 2018, nearly half of all US viewing is expected to be nonlinear. But as with online and mobile video growth, the rest of the world is following fast. (See Exhibit 6.)

Time shifting has changed what people watch and how they watch it because, as we discuss in more detail below, nonlinear viewing supports some content types better than others. Certain entertainment content, such as serialized dramas, encourages viewing in bulk (also known as binge watching), since it is easier to follow multiple characters and plot lines. Furthermore, some viewers prefer instant gratification to watching content that stretches out over months.

Many subscription-supported players have disrupted the traditional viewing ecosystem by taking a new approach to windowing. In the past, consumers who didn’t watch (or record) an episode of a favorite program when it aired at the time set by the network or cable channel had to wait (in some cases, several years) until the show was made available to rent, purchase, or watch in cable syndication. Now, subscription players (such as Hulu Plus) are stacking episodes so that consumers can watch current and past seasons, and they are rereleasing full seasons all at once, making seasons available for the life of the show (in some cases, up to a decade) so that consumers can watch at their leisure. In the UK, for example, drama series are the key driver of time shifting: some 40% of serialized drama viewing is now nonlinear. And our research shows that the vast majority of US consumers have binge-watched multiple episodes in one sitting. Binge watching is transforming the consumer’s viewing experience and adding value to the subscription players that have enabled the habit.

Not only is entertainment content changing, but news and sports have also been disrupted (and enabled) by OTT. For both news and sports, live content has always been critical. But choice and breadth were limited in the traditional TV environment, which constrained channel space for live, linear programming. OTT has unconstrained space for many more voices, opinions, and events, superserving far more niche audiences and interests.

OTT: A Concentrated Market?

Even though OTT has enabled the removal of market entry barriers and competition has heightened, the market is, in many ways, more financially concentrated today than it was in the traditional TV ecosystem. Five large global and semiglobal players compete across multiple markets and collectively control approximately half of the $25 billion of annual OTT market revenues. (See Exhibit 7.)

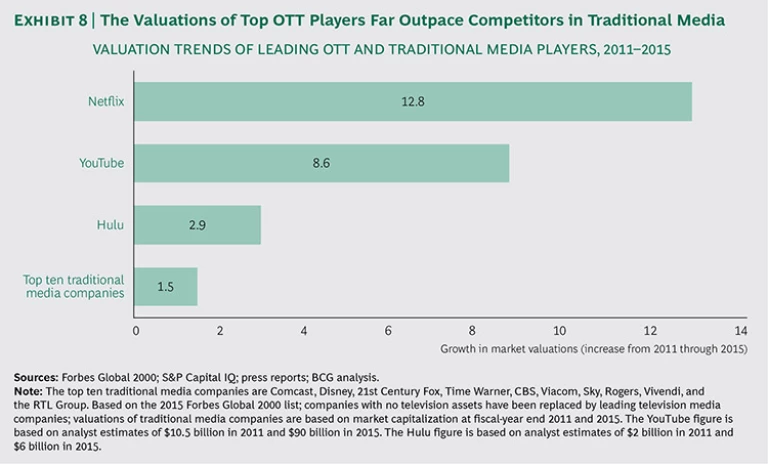

Of these five behemoths, Facebook and YouTube are focused primarily on ad-supported, pro-am, and amateur content. Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Prime deliver traditional professionally produced content and generate mostly subscription revenues. Together, the five companies have created enormous market value. Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube have grown many multiples above the index of traditional video media companies and have generated huge rewards for their owners. As of mid-2016, Netflix’s market capitalization was approximately $50 billion, while according to some equity research reports, YouTube was estimated to be worth as much as $90 billion, and Hulu’s value was pegged at some $6 billion. (See Exhibit 8.)

Local Players Respond (with Varying Degrees of Success)

As the consumer appeal and success of global OTT players continue to grow, local companies in many markets—new entrants and incumbents—have aggressively launched OTT services of their own. The bulk of financial value may have been created by global players, but most of the 500 OTT services are focused in a single domestic market.

There are a few examples of local success:

- In Germany, Maxdome offers a robust catalog of free ad-supported video, traditional professional as well as pro-am and amateur. It offers a subscription tier and a transaction-supported service for film and TV. Maxdome is a leader among German OTT companies, having captured about 15% of the OTT market by the end of 2015.

- In Southeast Asia, iflix is an independent upstart that operates in five markets. Its subscription-supported model includes a mix of acquired and originally produced domestic and foreign content. By the end of 2015, iflix claimed it had more than 1 million subscribers and had raised $90 million in funding. It has a fourfold competitive strategy: beat the large global players to market, undercut those players on price, offer temporary downloads to reach customers with low internet speeds and poor streaming access, and enter new markets through wholesale partnerships with telcos to drive marketing and customer acquisition activity.

- Sports programming, a fiercely local experience, has many successful local upstarts, just as video companies catering to niche sports audiences have unprecedented access to consumers. FloSports, based in Austin, Texas, for example, produces and airs a variety of sports events, including “Olympic” college sports (such as volleyball, wrestling, and swimming), catering to a fragmented but devoted audience led by former and current athletes. By mid-2016, FloSports had more than 100,000 subscribers, each paying $20 per month or $150 per year for access.

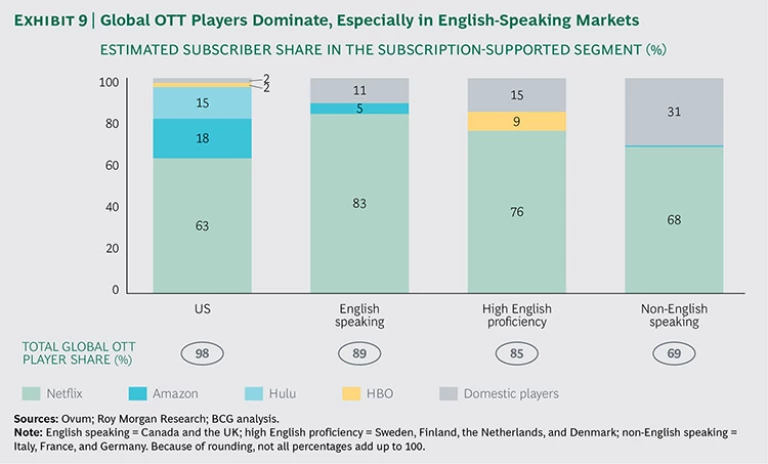

Despite these and other successes, however, gaining traction has been a struggle for most domestic-only players. In only a few of the markets where Netflix is present has a local player gained more than 25% of the subscription-supported market. OTT advertising market share, while more fragmented than subscription, is nonetheless concentrated among the big players, especially YouTube. And although many new domestic players have entered the OTT market, there have also been a number of high-profile exits, as domestic players struggle to keep up with the content and marketing costs required to compete successfully with the global giants. In Germany, ProSiebenSat.1 Media shut down its German MyVideo advertising-supported service, and Vivendi is rumored to be shuttering Watch-ever. (See Exhibit 9.)

The Revenue and Cost Strategies of Global Players

The top global players benefit from a series of structural advantages that enable them to enter new markets and win share with relative ease. From a revenue perspective, these include the following:

- Ready-Made Product and Content Offerings. Many global players are buying or creating content for global markets, and they have technology that scales easily for new markets.

- Customer Acquisition and Customer Service Expertise. Sophistication in acquiring subscribers, managing subscriber acquisition cost, and minimizing subscriber churn is critical to OTT success. Netflix, for example, has reduced global customer churn from 4.4% in 2008 to 3.5% in 2014, and it has honed its customer acquisition marketing machine, building its base to some 75 million subscribers—more than any traditional multichannel video programming distributor.

- Audience Scale and Diversity. Particularly for advertising-supported businesses, the ability to offer a diversity of audiences that range from big and broad to diverse and deep (in many cases, across markets) creates major go-to-market advantages for OTT companies. They can offer advertisers access to broad and hypertargeted audiences. YouTube has more than a billion monthly users globally, a number that no domestic player is close to approaching.

The big players’ cost advantages include the following:

- Buying Content Worldwide. The ability to acquire content across markets is a significant advantage for global players, which can easily bundle small new markets with existing deals in large mature territories.

- Original Programming. Creating high-quality programming means supporting a large fixed-cost base, albeit one that is smaller than it used to be. The more markets and—more important—the more viewers and subscribers over which an OTT player can amortize the cost of original productions, the more attractive its economics become.

- Delivery Costs. Back-end technology features significant economies of scale. For example, as total cloud storage grows, the price per unit (in this case, gigabytes of storage space) declines.

Herein lies one of the key questions of this report: Can the global titans of OTT sustain or even expand their global advantages in their share of time, revenues, and costs? How will this affect the economic activity accruing to domestic production ecosystems around the world?

The Evolution of Global and Domestic Content Production

It has been said that the video industry is currently in the Golden Age of TV. This is a broad generalization, of course, and probably a US-centric one at that. The telling question is this: Are all, or even most, production ecosystems experiencing boom times, or is the US industry feeding disproportionately off the global OTT video consumption trend? Who—from the genre, producer, and market perspectives—is really winning? And how is the competition affecting consumers’ choices?

A Golden Age

Global content production is booming, and the amount of content, the number of content creators, and the market value of content are all higher than ever before. In fact, content production dollars globally are expected to soar from $150 billion to $240 billion from 2011 through 2016, with an annual growth rate of 10%. OTT has been a critical source of this increase—not only as a buyer of content but also as a globalizing force that provides content creators with access to new markets and as a technology that eliminates traditional barriers to distribution and facilitates access of content creators to consumers and consumers to content creators.

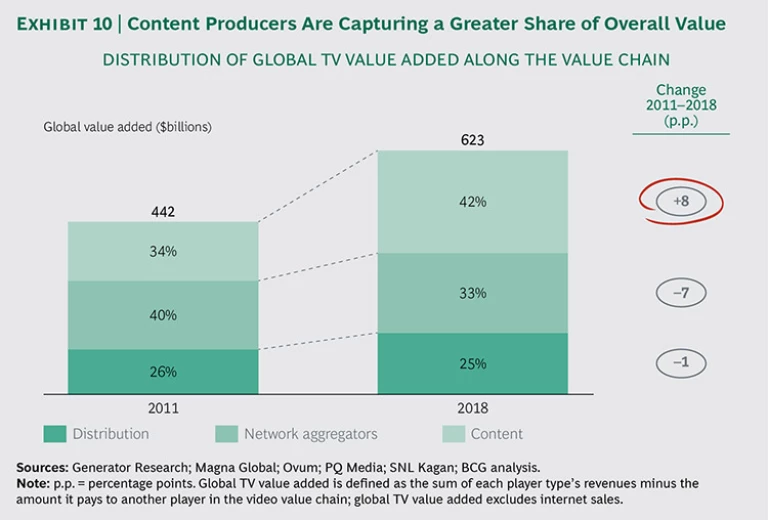

Content owners and creators are gradually increasing their share of the value captured relative to that of network aggregators and distributors, as the traditional TV ecosystem struggles with the loss of subscribers and advertising dollars to OTT. This isn’t true for all markets, of course. Some markets are at the apex of growth for pay TV and are supporting a healthy downstream value chain of participants, such as network aggregators and video distributors. For instance, in Brazil, which has been benefiting from the middle class and improving infrastructure, pay TV penetration has been increasing at 10% per year since 2010, with all traditional participants benefiting. And although there are players outside the pure-play video value chain that are creating real value and growing on the back of OTT (for instance, broadband service providers and content delivery networks such as Akamai Technologies and OTT enablers such as BAM Technologies), in most markets, especially developed markets, OTT is facilitating a value shift from traditional video distribution to content creation in the video value chain. (See Exhibit 10.)

The Collapse of the Middle

Not all content creators are created equal. This is both an unequivocal truth and a critical factor in the changing circumstances of global content creation. Trends in content production volume and the financial value it creates play out differently across the three tiers of content creators described in the previous chapter—traditional professional, pro-am, and amateur. Moreover, within the professional ranks, there are distinct subtiers with quite different circumstances and outlooks for the future.

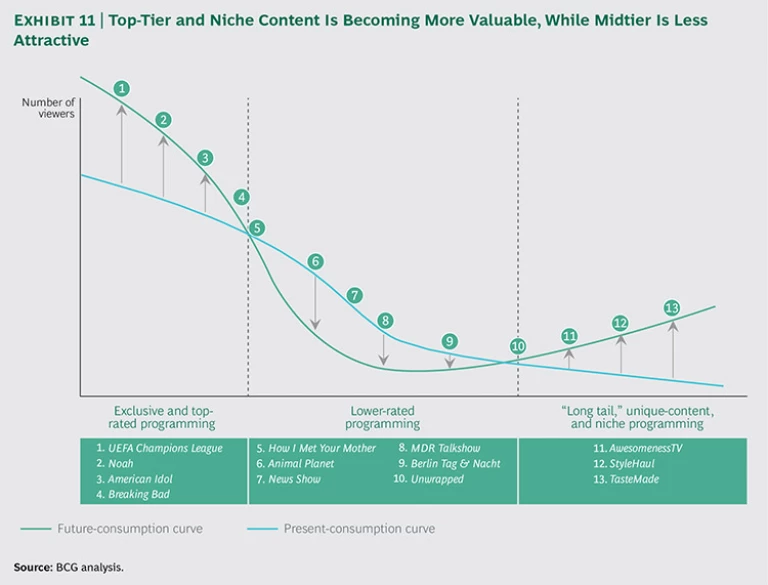

A second unequivocal truth is that the middle of the content market—mid-level quality content produced for a mass-market audience (what the US TV industry used to call the lowest common denominator)—is collapsing while the top and bottom ends thrive. (See Exhibit 11.) The massive increase in available content has simultaneously reinforced the importance of top-quality content in a cluttered world and enabled the superserving of endless niche audiences with almost infinitely narrow interests and desires. As one leading media industry executive put it, “Yes, we are in the golden age of TV for consumers: every need state can be satisfied. This strategy of appealing to all customer segments has come at the expense of midtier content, which originally tried to appeal to everyone.”

Top-Tier Professional Content. For professionally produced, English-language television content, this is indeed a golden age. Spurred by OTT demand, more professionally produced content is being commissioned than ever before, amid rising competition for consumers’ attention and wallets.

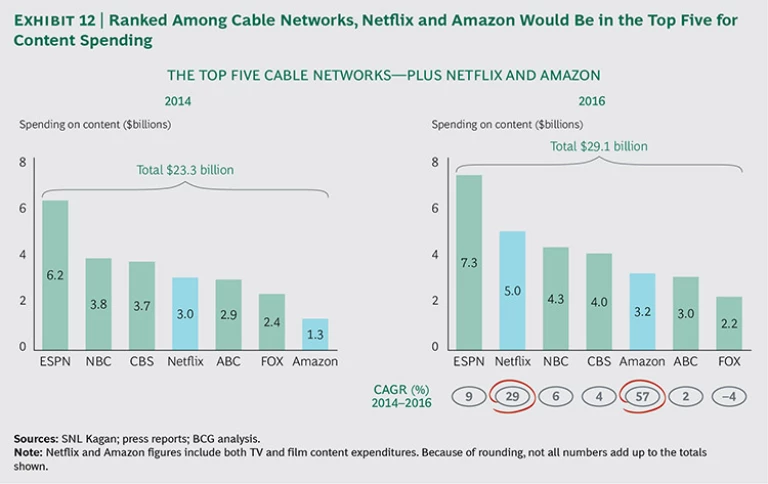

US producers dominate this tier. According to an analysis by the Los Angeles Times, more than 400 original US productions were greenlighted in 2015, compared with about 200 in 2009. OTT is at the forefront of this surge: Netflix and Amazon would rank second and fifth, respectively, in programming spending among all US cable networks—the top-spending cable networks in the world. (See Exhibit 12.) Not only are the OTT titans spending more, but they are also carrying their traditional competitors up the spending curve with them. OTT players are increasing demand (and the ability to pay) for original-content productions, requiring traditional players to invest more deeply in original content to differentiate and secure audiences in a far more competitive environment. The net result, at least for the near term, is that there is more competition for top-quality content, and unique content is more valuable than ever before.

The impact is most readily apparent in the categories of serialized dramas and children’s programming. These two categories are perhaps the most conducive to time-shifted watching, or binging, and they also travel internationally most easily. (In the UK, for example, about 40% of all viewing of serialized dramas takes place on a time-shifted basis.) One content executive who produces children’s content in Canada said, “I was going to retire five years ago, but OTT has unlocked so many new monetization windows for me—domestically and internationally—that I am making multiple times what I used to on most of my productions. The reason is simple: when we make a piece of animation in English and dub it in Spanish, it is in Spanish to Spanish children. Kids don’t know the difference. All they see and hear is SpongeBob, and on OTT, they watch it over and over again.”

Increased competition for top content has driven up prices at the expense of traditional distribution companies’ margins. This dynamic is most pronounced in marquee sports, as companies race to secure rights to the top events—the last bastion of must-see live content. For example, ESPN and Turner Sports bought the National Basketball Association (NBA) media rights for $2.6 billion annually in a nine-year deal that starts in the 2016-2017 season, a 180% increase over the previous near-decade-long contract. Not only does such programming guarantee high viewership, it is also the key to driving subscriber acquisition and retention and advertiser demand. Brands like the NBA guarantee audiences, and game viewing cannot be time shifted without losing all immediacy.

In non-English-speaking markets, the landscape for top-tier professional content is murkier. Again, sports programming is unique, and the cost of sports rights has been exploding around the world. The German Football League saw an 85% increase in its 2016 domestic TV deal, for example. Sports aside, despite a number of subsidies, tax breaks, and programming quotas, dollars flowing into original entertainment productions have not necessarily increased at the same rate in non-English-speaking markets. For example, in the Netherlands, which has a fairly stable pay TV ecosystem and significant government subsidies, investment in professional original programs has stayed relatively flat at €439 million to €459 million over the past five years. The number of productions has been flat as well.

Midtier Professional Content. Audiences are aging, content-viewing habits are evolving, and this combination is having a decidedly negative impact on the middle of the market. In particular, commoditized second-run entertainment, once the darling of the video world, is becoming less valuable for two key reasons: growth in the volume of new original content diminishes demand for reruns, and through time shifting, consumers have more opportunities to catch up on programs long before they reach syndication.

This one-two punch is having a cascading impact on upfront investment in two subgenres of entertainment in particular: sitcoms and procedurals. One industry executive told us that sitcoms are being replaced by reality shows because the latter are more predictable from both a production cost and an audience attraction perspective. “Realities do many of the same things that sitcoms do: they deliver light entertainment, laughs, drama, and water cooler value. But they are cheaper and far easier to get right,” she said. Procedurals, which are self-contained stories that do not build a plot over time, don’t work as well in the new on-demand viewing environment, where binging is often favored. Shows such as Law and Order and CSI, once staples of the content production ecosystem thanks in part to their cable syndication value, are no longer supported by exorbitant second-run fees. As another executive put it, “What used to be million-dollar-per-episode checks in syndication have become a few-hundred-thousand-dollar-per-episode checks. In a binge-watching environment, procedurals aren’t as much fun to watch.”

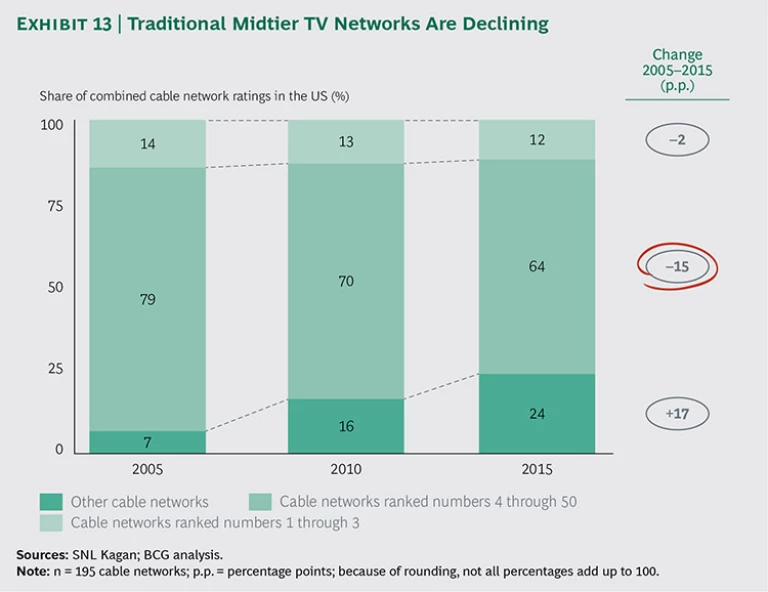

These trends are evident in traditional TV viewership. Top networks and niche networks are gaining audience share, while midtier general-entertainment networks in competitive OTT markets with mature pay TV ecosystems, such as the US, are declining. (See Exhibit 13.)

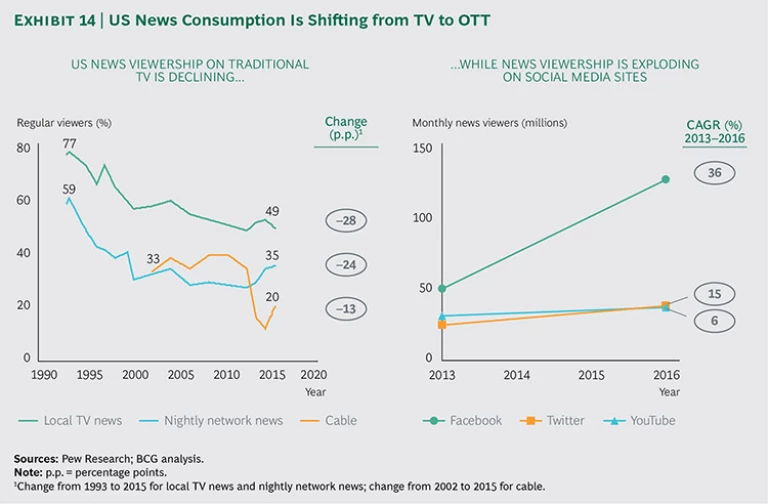

Niche Professional Content. With the decline in traditional television viewership of news and entertainment, backfilling has occurred in the form of niche content. Broadcast news in the US—national and local—has been declining significantly for years, but there are now at least a half-dozen cable news networks, each delivering its own point of view on many of the same newsworthy topics. These networks target niche audience segments, some of which comprise no more than a few hundred thousand viewers in prime time. On the internet, more than 100 OTT US news websites garner more than 1 million unique visitors per month. And this dynamic is not only in the US. Canada, for instance, has nearly a dozen OTT news websites with the same level of visitors. Virtually all of these sites feature significant video content, which would have been impossible over the facilities-based TV infrastructure. News has also been supported by the growth of social media as a distribution platform. Millions of consumers go to social media platforms as their core destination for breaking news, and, more often than not, this news is rooted in video. According to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 12% of consumers use social media as their main source for news. (See Exhibit 14.)

Some niche news formats have been created or reborn as a result of this shift. “News variety” shows, which sit at the intersection of entertainment and news (Last Week Tonight with John Oliver is a prominent current example), have become hugely popular as evergreen pieces of content that also have a long shelf life. The majority of Last Week Tonight viewing happens on a time-shifted basis on the internet. The TV linear audience for the program is about 1 million, but clips from the show on YouTube gain 2 million to 10 million views (and this doesn’t count people watching on HBO’s OTT apps HBO Go and HBO Now).

Documentaries have also been supported by this shift. Making a Murderer, a Netflix series, likely would not have been funded in 2005, but the long-lasting nature of the content and its ability to travel meant that the potential return justified the production costs. It became a hit in many of the Netflix markets. According to one media executive, “Documentaries were never mass market, but so many more are being produced today because they can hypertarget specific audiences, and some are even becoming hits.”

OTT has also had a huge impact on sports. Some marquee sports are establishing deep viewing relationships with fans through direct-to-consumer subscription services that emphasize live games, commentary, and analysis, compensating for some of the viewership loss on traditional TV. For instance, ratings for NBC’s coverage of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games were 31% lower than in 2012, but the lower ratings were offset by a surge in online streaming, with the cumulative audience producing what the NBC Sports Group chairman called “the most economically successful” Olympics in history.

At the same time, and possibly of greater impact, niche sports are beginning to thrive online because they can tap into pent-up demand from fans who, in the past, had no access to niche sports in the traditional TV lineup. For example, there are 7.6 million US lacrosse fans whose interests are being served by Lax Sports Network. Perhaps the best example is e-gaming. OTT first gave video game players the ability to upload clips of games, and this proved very popular among the broader community of game players. Twitch, which has capitalized on this phenomenon and now has more than 100 million unique viewers per month, was acquired by Amazon for nearly $1 billion. This is happening worldwide: dozens of OTT services are giving customers access to more sports teams, leagues, competition, and games than ever before.

Short-Form User-Generated Content. As discussed, a critical, but too-often-neglected effect of OTT has been the democratization of content creation. There is far more broad-based human activity than ever before: there are now nearly a billion “content producers” around the world. Pro-ams and amateurs are challenging the industry’s long-held belief that quality content is expensive and can be developed only by traditional production houses and studios with large production infrastructures. An episode of a top series on a broadcast network can attract 14 million or more viewers, but producing it can cost as much as $5 million. A top series on YouTube can reach several million viewers at a per-episode cost of well under $50,000—or a hundredth the cost of an episode of a professional series. And many viewers lap it up. It’s estimated that content from PewDiePie, a Swedish producer who hosts YouTube’s “Let’s Play” videos, had gained some 9 billion views by June 2015. Furthermore, according to the Swedish newspaper Expressen, PewDiePie had generated $12 mil- lion in annual revenues for his company, PewDiePie Productions. Another example: Tastemade, a food-focused video network that was launched as a channel on YouTube, racks up 700 million views a month, three times the online audience of its traditional professional rival, the Food Network. These, of course, are two of the top success stories, but they’re still powerful examples of value creation at the far end of the pro-am and amateur spectrum. As in the professional content world, the big successes are relatively few, but unlike in the professional ranks, the long tail of amateur production is very long indeed.

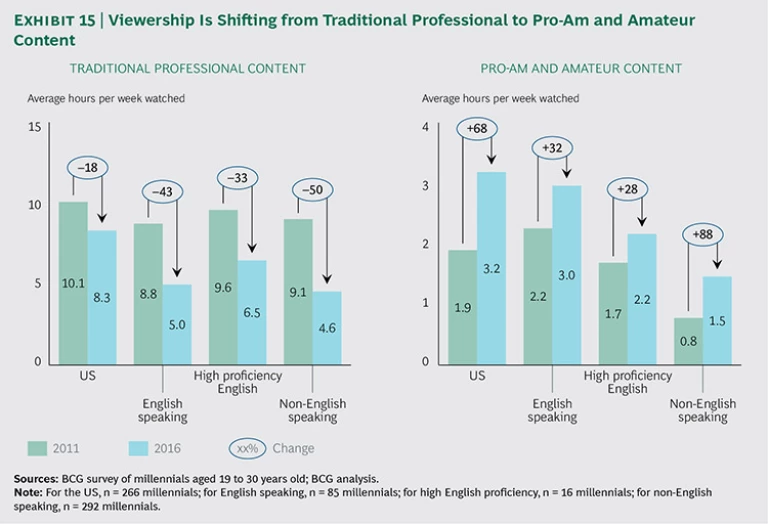

Amateur producers are also hyperlocal, and in many ways, they have replaced some of the domestic professional content development in the middle that has been squeezed out, especially in non-English-speaking markets. For example, blogger Clara Henry has become a national hit in Sweden, generating almost 60 million views on her YouTube channel, where she interviews people and does comedy sketches, all in Swedish. A BCG survey of college-educated millennials in 50 countries found that millennials are consuming a growing share of pro-am and amateur video content—a 30% to 90% increase, depending on the market, from 2011 through 2016. (See Exhibit 15.)

Some amateur content creators are quickly building large libraries of content—and audiences. Take, for example, social media celebrities Hannah Bronfman and Brendan Fallis. The couple, both New York deejays, started making social media content for their friends in 2012. As they gained followers (only some of whom they knew), they decided to make a greater investment in building out their social media platforms. Every week, using Snapchat and Instagram, they collectively create up to 100 minutes of video content that covers a number of lifestyle topics including sports, food, and fashion. They are now supported by a robust ecosystem of brand and marketing partners for whom they create bespoke content and focus on topics and stories that are particular to their hyperlocal context, interests, and causes.

Finally, while local professional productions in news and general interest may be waning, there is an explosion of pro-am and user-generated content that is filling that void—and then some. According to Pew Research, 12% of social media users have posted videos of news events to a social networking site.

Who’s Winning and Who’s Losing in the Entertainment Content Value Chain

Even though more content is being made than ever before, some players within the content creation value chain are benefiting far more than others. Three key forces affect individual actors across the entertainment value chain:

- New Models of Content Creation. Content creation is becoming less expensive, reducing barriers to entry. It is easier than ever to make high-quality, compelling content.

- More Competition for Content. Although demand varies slightly from market to market, there is generally more demand from both traditional and OTT players for high-quality, differentiated content.

- New Financing and Distribution Models. As more content buyers choose to own an asset not only for a short live or first-run window but also in second run, a new business model is emerging. Deficit financing, the traditional model for TV financing, is receding in importance. (Deficit financing is the practice of a content buyer, in many cases a network, paying a portion of the content costs for airing a given show but asking the program producer, in many cases a studio, to bear some of the risk. The reward comes in second-run windows, such as syndication and, more recently, OTT.) Increasingly, the roles of content creator (generally, a studio) and distributor (traditionally, a TV network or OTT service) have merged in today's cost-plus financing model. For example, Netflix has decided against selling its originals to third parties anywhere in the world. Instead, it holds on to global rights for exclusive distribution.

What impact will these forces have on the overall volume and quality of content and consumers’ access to it? And how long will the positive—or negative—effects last?

In the approximately 20 interviews we conducted for this report, industry executives and content producers described a variety of perspectives. Some of those we spoke with said that they are very optimistic about the long-term outlook, pointing to increased demand and monetization windows. Others said that they worry about an emerging bubble fueled by unsustainable demand. Others still are worried about the impact of content globalization in both non-US and non-English-speaking countries. We explore this question at the market level in the next chapter, but it is important in the context of assessing winners and losers to introduce here the broad arguments that we have heard.

The bullish case is highlighted by the notion that increased global and domestic demand for content, together with more monetization windows (domestic and international), will continue to drive growth. Optimists cite the globalization of content as a boon to content creation, especially in English-speaking countries. They point to the ability to now fully finance a program or series through international buyers and partnerships on the basis of the first run alone, diminishing the importance of deficit financing and creating only upside for producers in second-run windows. This school of thought also believes that non-English-language content is beginning to travel more easily and that the importance of local content provides a domestic balance to global players in local markets.

One example of such non-English content is Narcos, a Netflix series that is produced in English and Spanish and shot in Colombia. It has massive international appeal in as many as a dozen Netflix markets, and it caters equally well to native English speakers and Spanish speakers.

The bearish case is built on the concern that OTT will undermine the traditional ecosystem, that advertising and subscription dollars will dry up, and that investment in content will consequently be squeezed. At the same time, production and content acquisition across individual markets will become more international in nature, as domestic-only players cede share to multimarket buyers with stronger acquisition and distribution economics and greater purchasing leverage. This scenario suggests a perceived, and possibly real, threat to domestic producers’ ability to monetize content in international markets, despite positive trends today. It is worth noting that the naysayers do cite a few exceptions for non-English-speaking countries, including the following: local-market content is so important in some markets, for example, France, that it is immune to globalization; local-market content may travel better internationally from certain markets, such as Canada; and some local markets, such as India, have enough scale and monetization opportunities themselves to sustain high levels of both global and local investment.

While the debate continues, one thing remains clear: different types of OTT players have different opportunities and risks across the content creation value chain. A single structure does not apply in all markets, of course, but there are three broad types of traditional players, each with its set of considerations.

Studios, which are responsible primarily for the financing and distribution of content, are mostly North American and Western European players that are sometimes, but not always, vertically integrated with networks. Their opportunities include more demand from OTT players and traditional broadcasters for first-run original and second-run syndicated content, high international revenues that defer the first-run risk, and more windows for monetizing content.

On the downside, the value of financing and distribution, which are core studio services, could be disintermediated because of the declining need for deficit financing and the emergence of single buyers for all windows. In addition, the changing content economics from hit-driven to cost-plus production could cap the upside for top performers, and top-tier networks that launch new shows could take a share of downstream revenues in return for the value they provide in distributing an initial asset to a large audience in an increasingly fragmented world.

Production houses are responsible primarily for pitching, selling, and producing the video asset—that is, the show—itself. If it becomes easier to finance productions, thanks to quicker monetization models, production houses could increase their share of revenues by eliminating the studio role. Industry consolidation could lead to the acquisition of these companies at high multiples as others seek to secure access to unique production house talent. (In the UK, for example, a strong string of M&A activity has led to a decline in the number of production houses for public service broadcasters—from some 450 to about 250 over the past ten years.)

Risks include the following: the growing number of independent players that can now find distribution partners, increasing competition for talent, ideas, and monetization; talent going directly to consumers and disintermediating the production house role; and digital production houses that siphon off consumer and advertising dollars with profitable short-form, digital-first content development.

The talent—actors, directors, and production crews—face a changing world as well. On the plus side, there are more outlets (including for second-tier talent), thanks to the sheer volume of shows. One executive who is bullish on content said, simply, “Everybody is working.” A significant increase in activity means better chances of discovery for amateurs and pro-am talent. Top talent can go directly to consumers and capture both content creation and distribution value or force downstream players to pay more to recoup that value.

There are also risks for the talent. The ceiling on market value for top talent has never been lower, owing to the decline in the number of big hits and the fragmentation of viewing. One industry executive cited this as the worst-possible scenario for talent managers and agents. The production-plus mark-up OTT model is not creating the same level of upside. As another industry executive said, “This is the end of the road for the Seinfelds and Larry Davids. We are not creating hundred-millionaires with a single show anymore, no matter how successful it is.” The cascading impact of OTT content globalization could also put local talent at risk in non-English-speaking markets. Furthermore, although OTT has democratized content creation and enabled a billion pro-am and amateur content creators to participate, the distribution market is highly concentrated—dominated by YouTube and Facebook—perhaps even more so than traditional TV. The global players take as much as 50% of the revenues created on their platforms. The balance of power lies with the distributors, so while top stars are earning millions of dollars, there are millions of content creators who are earning little or nothing.

The Impact of OTT on Domestic Production Ecosystems

What is the net effect of OTT on domestic-market content production around the world? How is consumer content consumption changing as a result? Who’s creating local content, and who is profiting? What’s the balance between consumption (and production) of local versus global content? In each country, these are complex and multifaceted questions.

Other questions about the future of global and local OTT content abound. Will OTT players invest in local content in order to differentiate? Will domestic players be pushed aside and forced to cut content budgets? Are there opportunities for domestic producers to export more content through the global OTT distribution network? Should the production and consumption of amateur content, which would not exist without OTT distribution, be viewed through the same lens as professional content?

All of these are top-of-mind issues for both business leaders and policymakers. The former need to prepare strategies to protect their core business and expand into new markets of growth. The latter are appropriately concerned about their local markets from an economic (jobs and GDP) point of view as well as a social and cultural one. In the past, video content, which provides, perhaps, a richer experience than any other medium (at least until virtual reality becomes a mass-market reality), has had a substantial impact on economies and culture. In many markets, policymakers and regulators have supported local content production through various economic means. Most governments have ministries of culture charged with promoting the health of the country’s cultural identity and the growth of local production. Canada’s government, for example, promotes investment in local production through two channels: the Canada Media Fund, a not-for-profit organization that supports its television industry with hundreds of millions of dollars annually, and a robust system of provincial and federal tax credits for domestic production.

The disruption caused by the global OTT market’s rapid growth has caught the attention of policymakers and regulators. Various responses are under consideration. In the UK, for example, regulators are mulling a 20% domestic-market production quota for subscription-supported services such as Netflix and Amazon. The European Commission is considering similar measures for the EU overall. According to the research firm Enders Analysis, “This is driven by the core problem that the EU identified 40 years ago: that the Hollywood studios and other US producers dominate global box office and broadcasting because they have scale that cannot be achieved in the fragmented EU.”

But before policymakers and business leaders start to take action, they must understand what is really happening to domestic content, investment dollars, and culture as a result of OTT.

Language and Local Content Creation

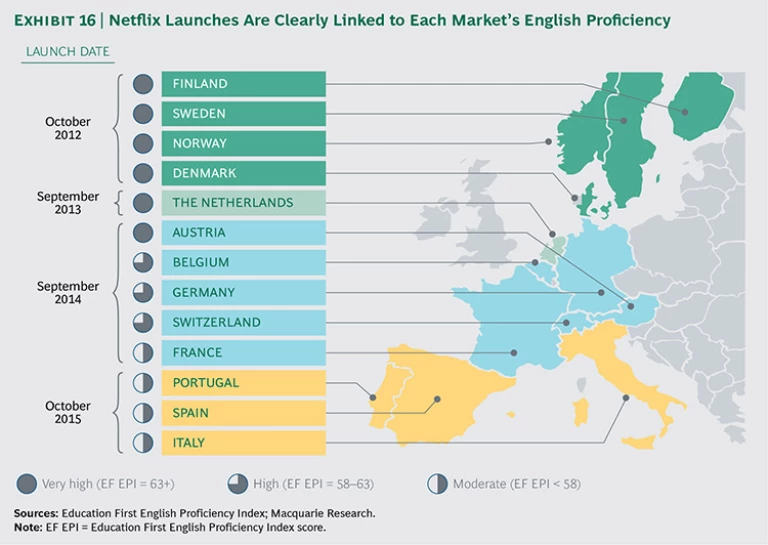

It is not surprising that language looms large in determining OTT’s market-by-market penetration. Because the global OTT players hail from the US, they have been quicker to move into other English-speaking countries and countries where English is widely used even though it is not the primary language. (See Exhibit 16.)

Language matters also in terms of the ability of locally produced content to travel to other markets and the level of domestic consumer interest in foreign content. Theoretically, non-English-speaking markets are protected against a massive shift in consumption to global OTT content since it is mostly produced in English. At the same time, non-English-speaking markets don’t have the same foreign-licensing revenue opportunities for their local content, because it is produced in their native languages.

To evaluate the impact of language, we examined four market categories:

- The US, a unique market, with by far the world’s largest volume of video content production

- Other English-speaking markets, such as Australia, the UK, and Canada

- High-proficiency-English markets, such as the Scandinavian countries, where English is widely spoken and understood

- Non-English-speaking markets, such as France, Germany, and Brazil, where English proficiency is moderate to low

We undertook an in-depth assessment of OTT across these markets, and at times, its impact on one representative country from each of these categories. These four countries are the US and Canada (English speaking), Sweden (high-proficiency English), and Germany (non-English speaking). Our examination included secondary research and proprietary BCG analysis, interviews with some 20 content production experts worldwide, and a short survey in which we asked more than 600 millennials in 50 countries about their interaction with content—foreign and domestic. Such an analysis carries imperfections, of course, as variables other than OTT have an impact on domestic-market content creation (for example, high growth in pay TV penetration, changes in subsidies, and changes in exchange rates), but we have attempted to control for those variables.

OTT’s Impact on Overall Content Creation in Each Market

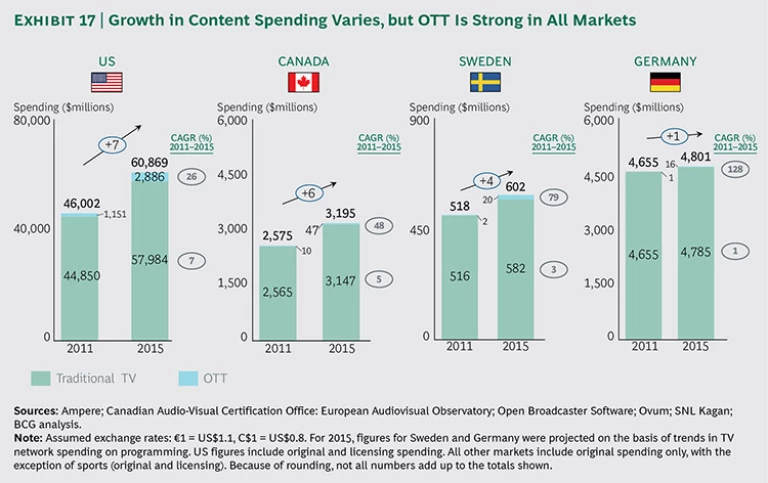

TV production and acquisition expenditures have been growing in the four markets we examined, with strong OTT increases helping to lift overall levels. (See Exhibit 17.) This finding indicates that, in terms of first-run content production and second-run content acquisition, markets around the world are at least as healthy as—and in many cases, healthier than—they were five years ago, before global and local OTT players emerged as a major force. Although the four-country sample is too narrow to provide conclusive answers, it does suggest that OTT entrants are fueling larger growth. The media executives with whom we spoke reinforced this view: approximately three-quarters said that OTT has had a generally positive impact on production dollars, globally and on a market-by-market basis. According to an executive at a Canadian children’s video producer, “The ecosystem has never been better for content production.”

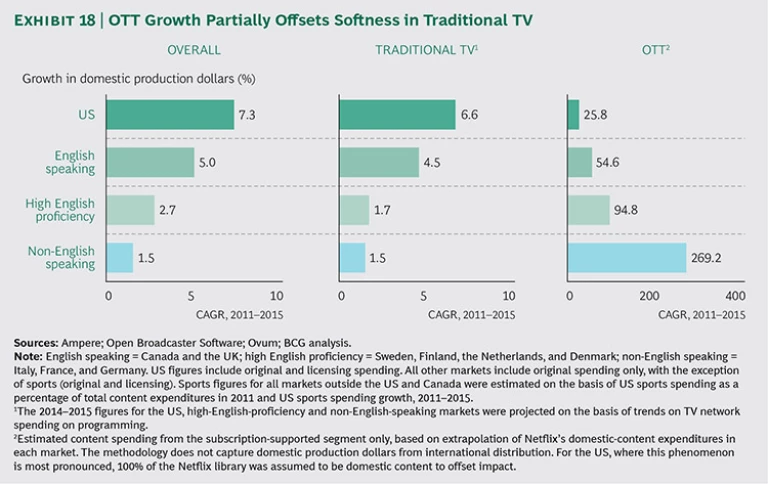

Specific trends, of course, vary significantly by market. English-speaking markets, led by the US, have clearly been benefiting most. Non-English-speaking markets do not reflect the same booming growth. Even though relative OTT growth is actually higher in non-English-speaking markets, the base is very small, and thus cannot offset slower growth in traditional TV relative to English-speaking markets. (See Exhibit 18.)

Why the difference?

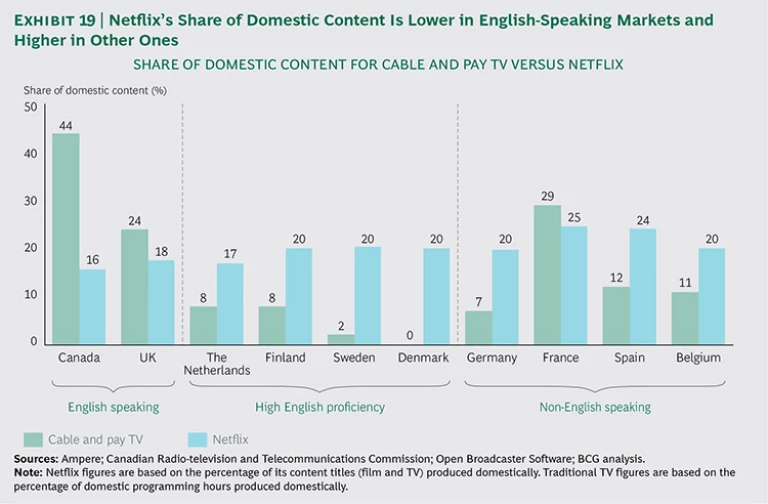

Global OTT players seem to compete more with local-language content (primarily acquired rather than original productions) in non-English-speaking markets than in English- speaking markets. Netflix, for example, has a higher share of domestic productions in non-English-speaking markets such as Germany and France than in English-speaking markets such as the UK and Canada. (See Exhibit 19.) The reasoning is that because most foreign content is in English, local-language content in those markets is critical for winning domestic consumers. One executive at a large Swedish FTA broadcaster explained, “Breaking Bad and House of Cards are important, but to win you need to supplement them with local titles—programs in the local language that people can relate to and watch without subtitles.”

Why, then, isn’t this leading to more local production in non-English-speaking countries? It comes down to the purpose of—and from that, the value of—the domestic content that is being bought.

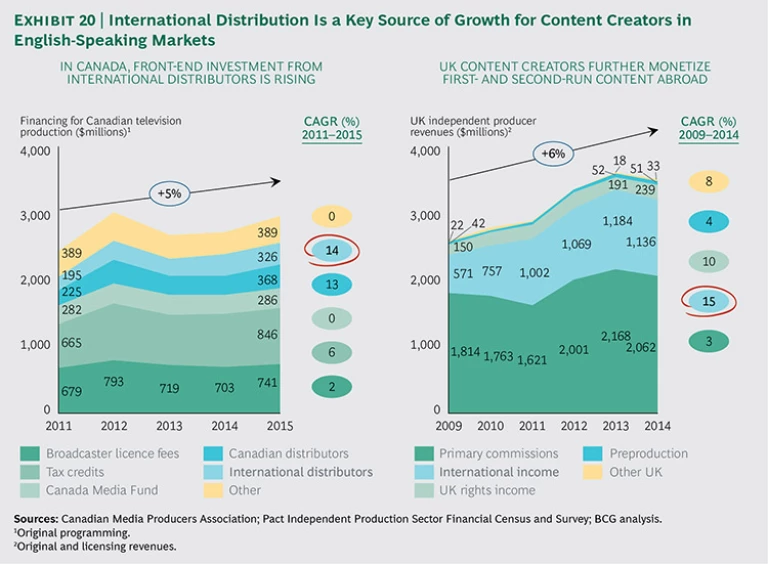

English content travels comparatively easily across borders. Because of this, domestic producers in, for example, Canada and the UK are benefiting from the trend of content glob- alization that OTT has enhanced. In fact, foreign distribution has been a key lever of growth in Canada and the UK, enabling domestic creators to further monetize their libraries by selling content abroad in first- and second-run windows. (See Exhibit 20.) Although the share of domestic titles from global OTT players is low, the material that is being acquired is typically big-ticket content for international distribution.

In non-English-speaking markets, distribution of domestic content is generally limited to the market of production. And although there are examples of non-English-language producers generating multimarket content (Germany’s Red Arrow Entertainment Group produced Bosch, one of Amazon’s flagship originals, for example), these remain exceptions. The scale benefits afforded by English-language content production create a barrier to non-English-language producers. “Most content in Sweden is made in Swedish. It is difficult to compete globally because the cost of making content is marginally less in Sweden but nearly impossible to sell abroad,” according to one Swedish content producer.

OTT’s Impact, by Programming Genre

In terms of content genres, domestic markets tend to follow wider global trends.

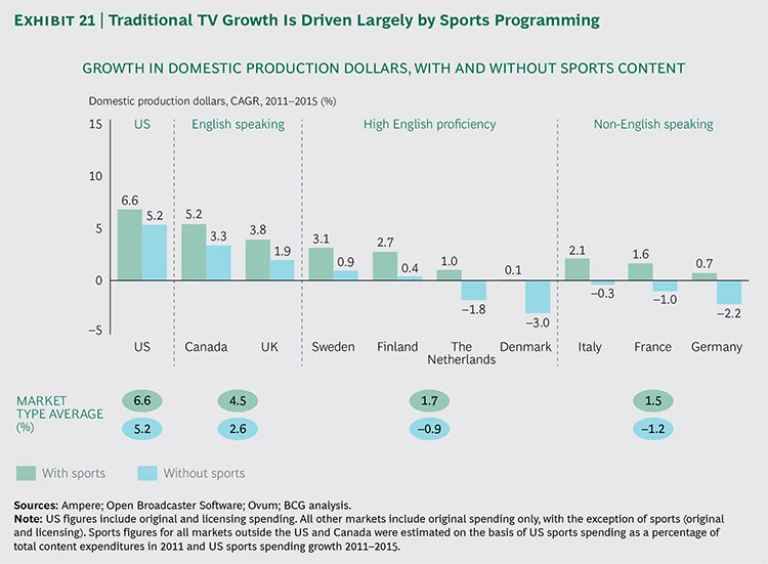

Sports programming remains a driver of domestic and global growth for traditional TV. In some markets, it is lifting otherwise flat or negative trends in spending for traditional TV content. Without sports programming, some markets, such as Italy and France, would be declining in terms of content production dollars. (See Exhibit 21.)

It is unclear, however, whether the increase in sports spending is having a cascading impact on jobs and local economies. After all, much of the rise stems from networks paying increasing amounts for the same rights: dollars flow directly to sports leagues, teams, and players rather than to writers, actors, and producers as in entertainment and other content genres.

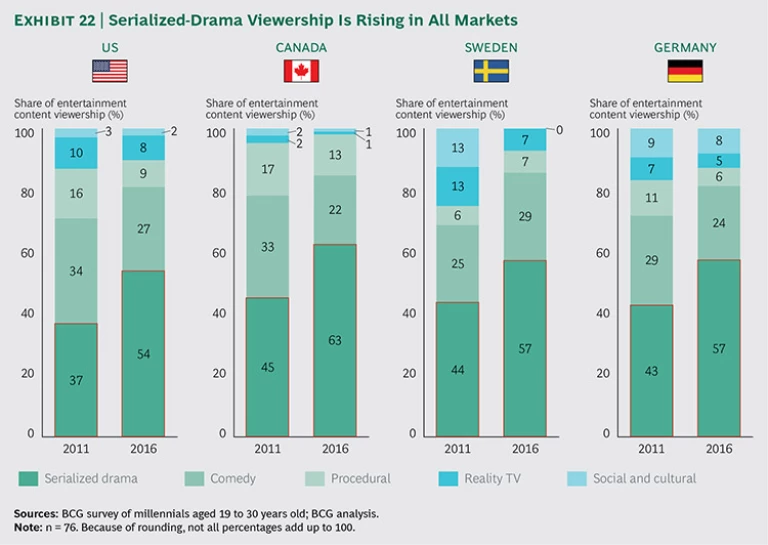

Entertainment and news also follow global production and consumption trends. The collapse of the middle—and with it certain content types, such as procedurals—was very evident in our survey. At the same time, demand for, and consumption of, high-quality serial dramatic content is increasing. These trends are market agnostic—English-speaking, high-English-proficiency, and non-English- speaking markets exhibited very similar consumer preferences. (See Exhibit 22.)

Forecasting the Future of Domestic Content Creation

In the long term, we expect spending on content creation to stabilize. There was no consensus among the experts on how long the current golden age will last, but many of the executives we interviewed said that traditional networks that have been cutting costs in other areas (such as SG&A expenses) would, as they come under competitive pressure from OTT services, have to moderate production spending as well. “With declining subscriptions and viewers, traditional networks will have a harder and harder time paying as much for content as they have been,” a former senior executive of a large US media company said. Many experts also believe that OTT players’ spending will eventually slow. “Global OTT players today are able to support their spending with their soaring valuations, but eventually that will go away, and continued growth abroad will put further pressure on costs,” a senior executive of a large US studio told us. Moreover, some expect the large global OTT players to reduce their share of spending outside the US as they focus on increasing original programming—primarily US productions—over licensed content. UBS analysts project that Netflix will raise its original programming budget from $1 billion to more than $5 billion from 2016 through 2020 while maintaining flat expenditures of $4 billion for licensed content.

That said, as we noted in the previous chapter, the trends in production volume and the financial value it creates play out differently by content creator type. There will continue to be more competition for top-quality professional content of all types (domestic and global), at least in the near term, and especially in English-speaking markets. The value of this content will likely continue to rise. This segment may also see a shift toward content that is the most conducive to time-shifted watching or binging and content that travels internationally most easily. In non-English-speaking markets, predicting demand, except with respect to sports programming, is less certain. Funding for high-end original entertainment productions has lagged behind funding in English-speaking markets.

Like networks, many middle-market entertainment producers, especially in English-speaking markets, will need to make a choice between trying to break into the top tier and moving toward producing more niche programming for OTT distribution. As TV viewership declines in most markets, especially among younger audiences, news producers will have little choice but to continue to focus on the growth of social media as a distribution platform.

Pro-am and amateur content will likely grow in importance as part of the competitive mix in all markets, and this is one area in which local producers can make a big mark, even if the financial impact of such content is unclear. A former executive of a large US digital media company said, “In recent years, you’ve seen the emergence of digital content producers, such as Supergravity Pictures, New Form Digital, and RocketJump. They are disrupting the market—redefining formats and cost models—and will very soon become important players in production.”

The Local Impact on Jobs and Culture

The assessment of two local dynamics—the creation of jobs and the impact on culture—is the last step in the review of the impact of OTT on domestic content production markets. Of the two, the employment impact is easier to quantify. Cultural impact can be amorphous, but it is of critical importance to national identity—especially to culture ministers who are charged with maintaining the voice and identity of their countries and people.

Job Creation. It is important to examine employment through two lenses: professional activity, which is made up of, for example, full-time content creators, producers, writers, directors, editors, and actors, as well as pro-ams and amateurs, who, although they are in many cases not full-time content creators, do represent a significant uptick in human activity around content creation.

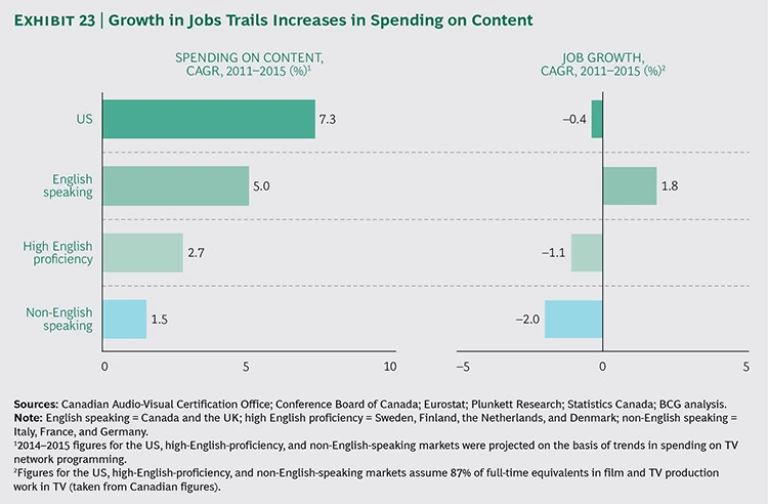

In professional content, growth in production dollars is not necessarily translating to more job activity. In nearly every market observed, irrespective of language, job growth lagged behind the growth in production dollars. (See Exhibit 23.)

The immediate question: Why?

One hypothesis is rooted in the collapse of the middle market for content. More and more producers are reallocating midsize-budget projects to either big-budget productions or lower-market niche productions. Since big-budget productions generally have higher fixed costs (such as top actors or on-location filming) as opposed to variable costs (such as the number of production people), the number of production jobs (preproduction, production, and postproduction) doesn’t necessarily increase. Furthermore, sports programming is driving a significant portion of the growth in content creation. The added costs in such programming are related more to license fees than to production personnel, with the rights to marquee sports—whether the Bundesliga or the National Hockey League—rising by double- or triple-digit percentages in recent years. What’s more, production houses have been consolidating, primarily as a result of private-equity-backed M&A. This has pushed production houses to, as the CEO of a UK broadcast company put it, “increase focus on cost cutting and margins” and evaluate all areas of expenses, including head count. Finally, the rise of production dollar spending seems to be driven more by the increase in the price than by the volume of content. This dynamic held for the four markets we assessed, where production volume trailed dollar growth, was flat, or was negative.

From a pro-am and amateur perspective, there is clearly a significant increase in content creation activity. And although the value created by these players is concentrated at the top end of the market, they do represent a long tail of local content creators, with very little variance across English-speaking, high-proficiency-English, and non-English- speaking markets.

Culture. How is domestic market culture changing? Are national identities at risk? Again, it is instructive to review this on a professional- and nonprofessional-content level.

In terms of professional content, one indicator is the share of domestic content as part of the overall mix on traditional TV networks. It is very difficult to capture reliable data on this. However, a review of Sweden’s channel lineups of the top-tier broadcast and cable networks suggests that for the most recent 15-year period, there has been little change in the volume of domestic programming available to consumers, and domestic programming on some channels, such as SVT1 and TV4, actually rose in that period. It is interesting to note that this pattern holds for FTA networks, which are subject to strict quotas on domestic content, as well as pay TV networks, which are not.

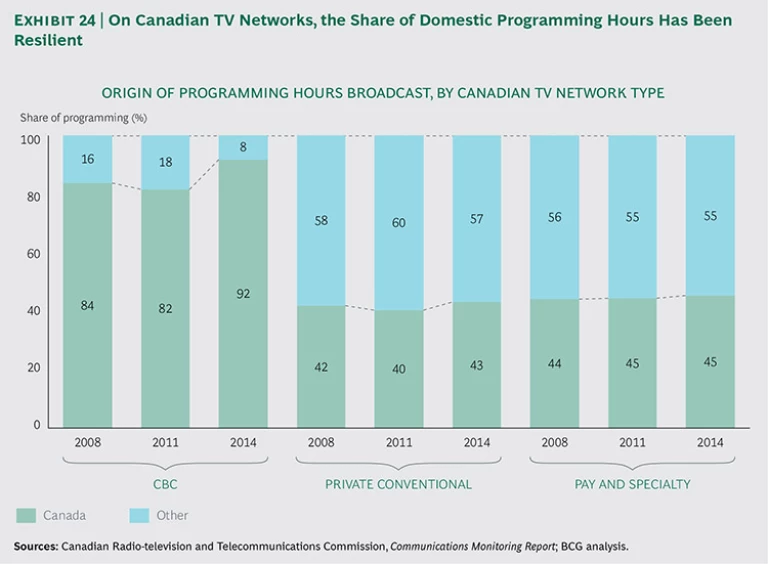

The same dynamic seems to hold in English-speaking markets as well. In Canada, for example, the share of domestic programming on CBC Television, conventional, and pay and specialty channels either stayed flat or rose from 2008 through 2014. This may be, in part, a result of domestic networks’ efforts to differentiate themselves from Netflix and other US-dominated OTT options. (See Exhibit 24.)

Among global OTT players, however, there is a clear focus on developing big hits with global appeal and, as discussed above, the expectation that this will intensify as players raise their mix of original programming over licensed content. This already seems to be having an impact. Our survey of millennials showed, for instance, that the share of their viewing of traditional professional content made up of local stories fell nearly 5 percentage points—from 58% to 54%—from 2011 through 2016.

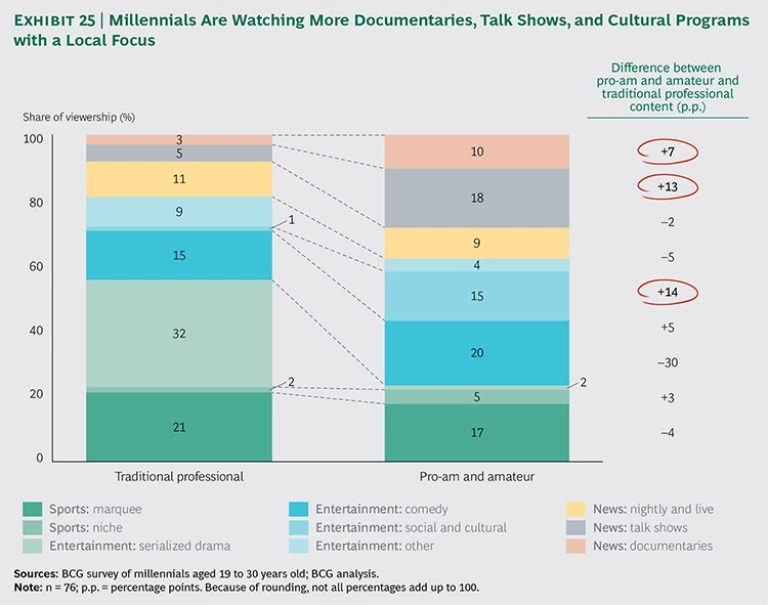

If this paints a negative picture for traditional professional content, then the pro-am and amateur content trends paint an undeniably positive one. Some believe that pro-am and amateur content is primarily US dominated, but our survey showed that millennials watch the same amounts of domestic and foreign pro-am and amateur content. This represents a higher share of domestic content than what is shown by most cable networks on traditional TV. Also, contrary to the trend in traditional professional content, the share of local stories in pro-am and amateur content has actually been rising in recent years.

Finally, millennials are watching more news and culturally relevant shows from pro-am and amateur producers than from traditional professional content creators. Millennials’ pro-am and amateur content viewing reflects a greater mix of documentaries, talk shows, and social and cultural programs with a markedly local focus. (See Exhibit 25.) A Swedish TV expert told us that “the blogger space is pretty big in Sweden. The number of unique visits as a percentage of the population is very high: some shows have half a million or a million unique hits per month.”

While this anecdotal evidence is in no way definitive enough to assuage concern about risks to the local cultural fabric that the globalization of content might create, it will be imperative for policymakers to carefully study this rapidly changing landscape of pro-am and amateur content viewing and not focus only on the traditional definition of content creators. Otherwise, it would be analogous to regulating or providing incentives for the production of vacuum tubes during the 1960s or buggy whips at the beginning of the 1900s. Consumers are getting their news, information, entertainment, and connectivity from a variety of sources, and the format for “local storytelling” may very well be changing irrevocably.

Moreover, as policymakers weigh policy decisions, there must also be a change in how those local-content policies are designed. Content regulations today are based on supply (for example, European governments are considering regulations that require 20% of Netflix’s content library to be domestic), but such regulations do not effectively apply to OTT, in which supply is unconstrained and local content is easily lost among thousands of other titles. It would seem more appropriate for local-content policies to focus on demand, but demand cannot easily be controlled. There is no easy answer, and policymakers will need to adopt an entirely different mindset and approach to this issue.

In summary, it is hard to conclude that OTT’s impact on video production ecosystems overall is not positive. Although, perhaps, it is not as positive in every area as everyone might like.

The removal of barriers to distribution and the resulting explosion in new—and new kinds of—content, as well as new ways of viewing it, are all boons for consumers. While there is concentration of share at the top of the OTT market, the opening of new markets to producers has led to greater revenues and value, if not a commensurate increase in jobs. The latter may be a somewhat illusory disappointment. It’s highly unlikely that there would have been big increases in video-related jobs if the OTT market had never come into existence.

There are legitimate concerns about the potential impact of globalized OTT programming on local culture, but these may be partially counterbalanced by the ability of anyone anywhere to become a content producer and showcase his or her local culture on a global stage. The output of a billion content creators—representing all manner of backgrounds, societies, cultures, and points of view in a way that was unimaginable 20 years ago—cannot be ignored. In this context, OTT has democratized both the production and the consumption of content to an extent never before seen. Is that sufficient to serve local societal and cultural needs and fulfill the objectives of policymakers? If not, how can policymakers support local content when the traditional regulations on supply don’t effectively apply to OTT? These are tough questions to answer, but it is absolutely clear that the evolution of consumers’ viewing habits and sources of content means that the traditional thinking about content creation needs to evolve as well.

All in all, OTT is an evolving story that bears close watching.

Acknowledgments

This report draws in part on work for a North American telecommunications and media company.

The authors are grateful to David Duffy, Matthew Glotzer, Hilary Higgins, Fredrik Lind, Mickie Rosen, Jacob Rosenzweig, Ken Whyte, Lauren Zalaznick, and the industry executives who participated in the interviews. The authors appreciate their support in the research and content development for this report.