An effective board of directors may not guarantee that a company will succeed. But an ineffective board can go a long way to ensuring failure, because the consequences of its attitude and operating model will trickle down into the business. The boardroom should not be just a place from which directors oversee the executive. Boards typically boast decades of senior experience, which directors have an obligation to leverage in order to add value to the business. This means that the board has a role to play in triggering—and subsequently overseeing—transformational change.

The rules and practices of corporate governance impose on the board many constraints and competing demands. In the finite time available to deliberate and make decisions, the board’s agenda naturally gravitates toward the essential issues of the day: governance, regulation, compliance, and near-term decisions. Often the board’s attention to the long term is relegated to its participation in determining annual strategy. In many companies, this is a flawed process.

Notwithstanding the packed schedule of most board meetings, the experience and detachment of board members position the board to be an actively engaged catalyst for change. Such a board will be able to identify, interpret, and act upon weak signals inside and outside the business that indicate the need for change; it will be adaptable, changing its composition and operations to meet evolving needs; and it will balance the independence of position and mind required for oversight with the active engagement necessary to provide management with the benefit of its members’ experience.

The Challenge

When we embarked on our interview program with board members, we intended to examine only the board’s role in triggering and overseeing transformational change. But we found that an equally fertile area of exploration was some of the impediments to a board’s ability to act sooner or more decisively.

Competing Demands

Egregious failures often spark vigorous and well-intentioned reactions. Sometimes those reactions obscure other important issues. The collapse of Enron made headlines around the world. As became apparent, its board had paid insufficient attention to the off-the-book entities that ultimately brought about the company’s downfall. In response to this (and other problems), a flurry of corporate governance regulations were imposed over the ensuing 15 years.

Yet over the same period, we saw a succession of failures at major companies, from scandals of executive conduct in the banking and pharmaceutical industries to accounting scandals at venerable Japanese corporations to the emissions-testing scandal in the auto industry. Companies involved in many of the highest-profile scandals share strikingly similar characteristics: a dominant CEO; a culture that limits the board’s ability to challenge management; nonexecutive directors (NEDs) who lack industry knowledge and experience (and, sometimes, too few of whom are independent of the company); a dysfunctional company culture; and overly complex business and accounting arrangements.

In the case of many well-known failures, the industry drums were beating long before the board became aware that trouble was at hand. In hindsight, significant warning signs were clearly missed. Some argued that the board could have uncovered the problems if only it had read the warning signs and acted sooner. So the fault had to lie in deficient board processes. Unsurprisingly, politicians, regulators, and the media started imposing unprecedented scrutiny on corporate governance.

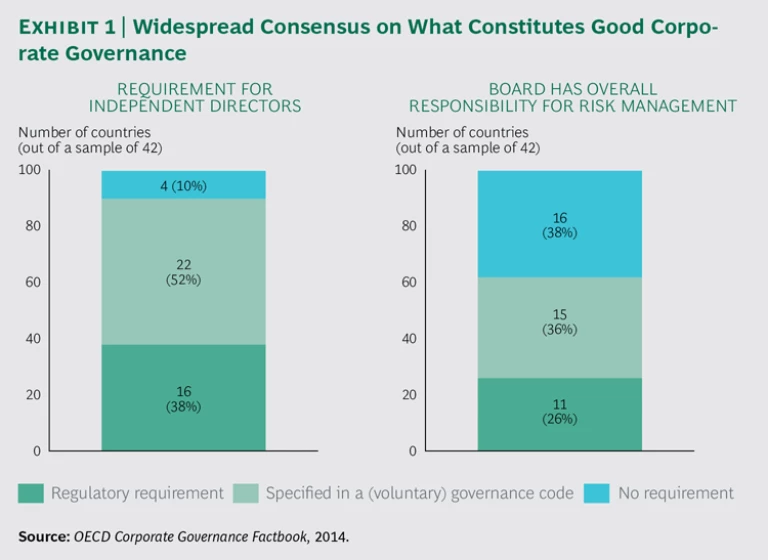

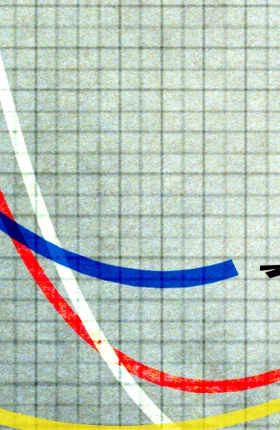

The result is that over the past several decades, a consensus has built up among the custodians of corporate governance about what “good governance” looks like. (See Exhibit 1.) The two most important consequences have been initiatives that attempt to do the following:

- Strengthen the board’s independence by shifting to independent directors, independent leaders, and (in some countries) recommended term limits.

- Increase the board’s responsibilities, with an emphasis on strengthening oversight of internal controls and operational execution.

In most countries, good governance has been incorporated into national codes of practice, with companies increasingly complying with these codes or else having to explain any noncompliance.

The additional demands of governance codes come against a backdrop of increasing business complexity, greater competition, rapidly changing technology, and rising market volatility. This has made the role of boards significantly more challenging, with many admitting that they struggle to fulfill their obligations with the limited resources at their disposal.

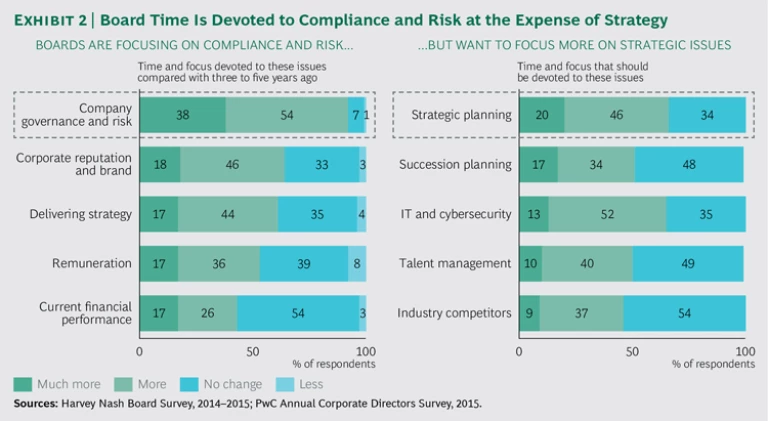

The result is that boards spend ever more time focused on formal risk and regulatory matters. This reduces the time available to explore strategic issues, raise nagging doubts, or discuss any indications that the company may need to transform itself. (See Exhibit 2.) So while boards are generally much more engaged than they were a few decades ago, their energy is almost entirely devoted to compliance and reporting. As one senior director told us, “You can go to jail for misclassifying short-term liabilities as long-term debt. But nobody gets into trouble for messing up the strategy. The balance is out of kilter.”

Corporate governance rules are important—but by themselves, they cannot help a company identify the signs that it needs to change course. For that, we need more actively engaged boards.

Obstacles to More Effective Engagement

Identifying the need for change is primarily the responsibility of management. Invariably, management knows much more about the business than a part-time independent board can. But if management does not recognize the need for change, the board must be asking the right questions so that it can step in and trigger the right course of action (which may include replacing some executives). However, there are impediments that can undermine the ability of boards to play this role.

The Need for “Independence.” Boards often deliberately limit their engagement with the business, struggling over where to draw the line between oversight and management. As one director put it, “It’s difficult to step in—to encroach on what management feels is their territory. It creates real tension.”

While independence of mind is the critical attribute necessary for board directors to do their jobs, it cannot be gauged by any of the so-called measures of independence, such as not having been an advisor to the company or not having been a director for more than a certain number of years. These are surrogates at best. And in fact, these requirements can actually restrict a director’s effectiveness. Most companies have well-developed and well-justified protocols to ensure that NEDs do not intrude inappropriately on executive matters. The result is that board members are typically far removed from what is going on.

Board Composition. Because of competing demands that shape their membership, some boards lack the technical and industry expertise needed to challenge management effectively. In fact, rules governing independence can make it difficult for companies to recruit board members with strong industry experience. Others find that their directors are not sufficiently plugged into a wider network that would enable them to know what is being said about the market and the company on the outside. All boards find that their main source of information about the company is the management team.

Boards can benefit from having serving executives as NEDs. Executive experience can give directors a nose for problems and challenges. However, it is increasingly hard for serving executives to commit the time required to serve as directors. Additionally, the modern practice of having fewer executive directors serving on boards means that independent directors have less exposure to the executive team outside of controlled, set-piece events such as annual strategy sessions.

Quality of Information. One of the greatest challenges facing boards is asymmetry of information. Many members complain that the information they receive is overly filtered by the executive team, often reflecting yesterday’s issues rather than providing forward-looking stimulus. As one director put it, “Boards are the last people to know when something’s going wrong.”

External experts can provide an outside perspective, but some boards are reluctant to use such support extensively for fear of creating an adversarial relationship with the executive team.

How Boards Spend Their Time. Even when they have the right information, boards find it increasingly challenging to devote sufficient time to interrogating it. This is in part because of the increased demands of good governance. “The board is so clogged up with compliance and litigation and regulatory stuff that sensible, forward-looking discussion gets crowded out,” said one director.

Boards are also under pressure from investors to produce continually improved short-term performance. This can lead them to focus on short-term financials at the expense of the long-term stewardship that drives a healthy company. Even though European companies are no longer required to generate quarterly financials, for example, many still produce some form of quarterly report.

Topics that can get squeezed for time are often those that might provide clues about needed change; these include external trends and perspectives and horizon scanning for risks and opportunities. As a consequence, boards can rely too much on the annual strategy process.

Social Psychology of the Board. To be effective, a board must be willing to have difficult conversations, learn from failures, and challenge the status quo. This can happen only in the right atmosphere. As one director observed, “It comes down to how much trust there is around the boardroom table, so people are prepared to ventilate concerns in such a way that everyone doesn’t become defensive.” Unless the board gets the balance right between support and challenge, it will always fail to have the conversations that are needed.

A board needs to have the right relationship with management. The default mode of supporting management is appropriate but can become a barrier to having the proper conversations. The phenomenon of a dominant CEO and a board so seduced by past successes that it fails to act quickly enough to bring about change is an all- too familiar one. Even in less extreme situations, boards have a bias toward supporting management, particularly during the good times. “There’s inertia in the system,” said one director, “especially with successful CEOs and long-successful companies. Success makes it difficult to intervene.”

But the opposite situation, in which boards are excessively in challenge mode, can also fail. No progress can be made if board members have a tendency to shoot the messenger whenever bad news is reported or when they take delight in scoring points.

Boards can also be risk averse, reluctant to take action swiftly enough. Change is hard: it creates work, requires difficult decisions, and has consequences for the reputations of directors. Moreover, the signs can be unclear, even contradictory. Like the frog in the pan of warming water, it can be difficult for a board to know when the time is right to jump out.

A Way Forward: Redefining Board Engagement

To meet some of these challenges, boards must tread a fine line between active engagement and intervention. An actively engaged board combines information from a wide range of sources in order to truly understand the business. It focuses relentlessly on value-added engagement. It is prepared to make tough decisions. “The time of just reading the papers and turning up to monthly board meetings is gone,” observed one director. “Today, boards have to be much more engaged with the organization. I can’t see how you can make a proper contribution unless you are—in both formal and informal ways.”

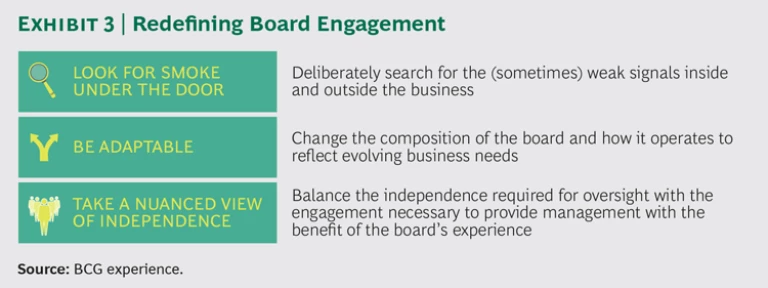

Experienced directors describe three common features of more engaged boards (see Exhibit 3):

- They look for “smoke under the door.” They deliberately search for the sometimes weak signals within and beyond the business that indicate a need for change.

- They are adaptable. They change the board’s composition and how it operates to reflect evolving needs.

- They take a more nuanced view of independence. Adaptability requires that they balance the independence of position and mind required for oversight with the active engagement necessary to provide management with the benefit of the board’s experience.

Looking for Smoke Under the Door

Sherlock Holmes was asked in one tale whether there was anything to which he wished to draw attention. He replied, “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.” When the surprised policeman pointed out that “the dog did nothing in the night-time,” Holmes observed, “That was the curious incident.”

Assessing the implications of what you can see is not always easy; trying to determine what might be missing is even more challenging.

Boards often use the annual strategy review process to identify the need for change. At the annual offsite, they review the current business model, assess performance, examine trends, and undertake scenario planning. But many companies are now too large and complex for sensible strategy discussions to take place at the strategy retreat. The offsite would work much better if it were the culmination of a series of discussions that have taken place throughout the year.

Many boards work with the CEO to set the strategy agenda and the offsite agenda. An engaged board will periodically come to an agreement with the executive team on the handful of key strategic issues that need to be addressed. This allows directors to explore issues of concern. Some boards prefer to help shape the discussion and the options; others prefer to debate management’s recommended strategy. At one company, the CEO meets with each NED six months before the retreat, identifies issues, and circulates relevant materials in the months leading up to the session so that “everybody’s head is in the game.”

As useful as the strategy sessions are, for many directors it’s the discussions with members of the executive team in between the formal sessions that are most valuable. Through these conversations, directors can get a feel for the real issues that concern management. One practice that works well in some companies is to organize an informal discussion before each board meeting—perhaps for an hour or so—with an executive in charge of a business or project of importance to the company. There is no agenda or presentation, simply a discussion about “what is keeping you awake at night.”

Done well, the strategy review process can be quite effective in identifying warning signs that could indicate a need for change. But this process is insufficient by itself, since typically it is not effective at spotting unknowns, such as inappropriate risk taking. And it can be hard for boards to know with certainty how much changes in company performance are driven by external factors (changing markets, regulations, technology, or competition) and how much by internal factors (leadership, organizational capabilities, or culture).

To answer these questions, boards need to look for signals that change may be needed. Typically, they will not miss strong signals, such as obvious failures of performance. But they are less effective at spotting or responding to weaker signals. Important areas to explore include:

- Failures of Leadership. It is crucial to identify quickly an overly dominant CEO—or a complacent one. As one board chairman observed, “When CEOs start, they’re grateful for the job. In the middle, they hear the applause and start to feel entitled. At the end, they either wake up or continue to hear the applause long after they should.” Boards are not always quick to recognize the part of the cycle that they’re in.

- Failures of Culture. Boards are the ultimate guardians of the company’s culture and values. They need to be adept at recognizing warning signs, such as when “results” are valued over integrity or earnings quality, when staff dissatisfaction or customer complaints increase, or when suppliers are unhappy.

- Too-Good-to-Be-True Scenarios. As one NED succinctly put it, “If the company is making incomprehensibly large profits, the board must question whether they are genuine, legal, and sustainable.”

- Changes in the External Environment. Boards should assess how social, demographic, economic, technological, environmental, regulatory, and other trends will change what it takes to win in an industry. It is, of course, generally easy to recognize major new patterns once they are established. One director observed: “Technology is disrupting all our businesses. You don’t have to look far to see the businesses that are taking responsibility for addressing that disruption and those that aren’t.” The challenge is knowing when to take the early warning signs seriously.

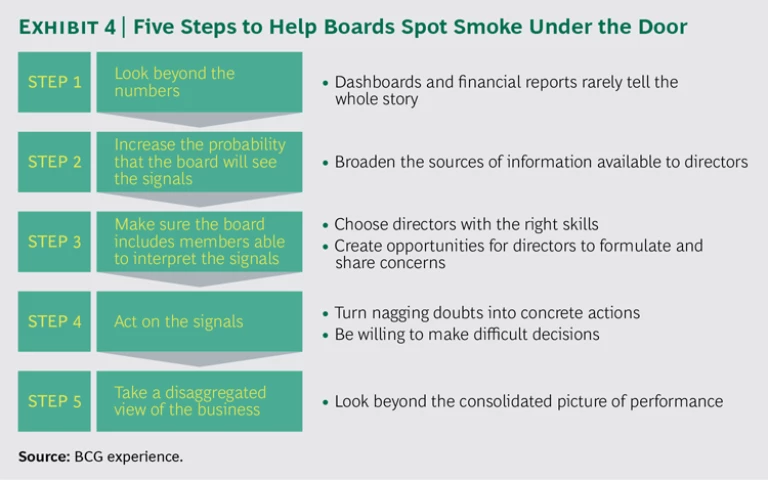

Boards have a limited set of resources available to them: typically, 8 to 17 members committed to approximately 30 days of service per year. (Many board members would argue that 17 members is too many for meaningful discussions, with debate often nothing more than a series of individual pronouncements.) However, an actively engaged board leverages these resources to take five steps that can help it gain a real sense of the company’s health. (See Exhibit 4.)

Step 1: Look beyond the numbers. Any board needs to get a proper grip on the company’s financial performance. This can be easier said than done. The technical complexity of modern accounting makes financial performance difficult to gauge, especially when reports include a mix of real and value-adjusted numbers. And dashboards and numbers rarely tell the whole story. Strong financial performance is not necessarily the same as high-quality or sustainable earnings—as banks discovered during the financial crisis. Moreover, financials are typically a lagging indicator of performance problems.

An excessive focus by management on meeting financial forecasts can also be a warning sign of troubles to come, indicating a culture that values delivering at all costs, potential underinvestment, injudicious squeezing of costs, or price and margin behaviors with long-term negative effects. Strong financial performance is seductive. Good performance should be interrogated just as carefully as weak performance.

Step 2: Increase the probability that the board will see the signals. Boards should constantly seek imaginative ways to increase the information available to directors. (Top management needs to do this, too. In many corporate failures, it is not only the board that is blindsided but top management as well. They have a common interest here.) Many boards already make some use of alternative information sources, including social media, customer complaints, whistleblower logs, staff surveys, and exit interviews. They incorporate forward-looking and cultural metrics into performance reporting. They listen closely to what the company’s customers are saying. And they leverage the knowledge and experience of internal and external auditors to help scan for potential challenges. Information is often there, but the board must know where—and have the time—to look for it.

Most valuable are those sources of information that distill large amounts of data, such as customer satisfaction or employee attitude surveys and investment analyst reports. In contrast, care must be taken with anecdotes picked up in random discussions in the car park.

Informal discussions with staff and managers are another important source of information and an unfiltered way of taking the company’s pulse. Conducted with sensitivity, so as not to undermine management accountability, such discussions will not compromise the board’s independence or management’s authority. Increasingly, directors do spend more time at the company, although many feel constrained about how much they should walk the corridors. One chair of a major public company sits at a “hot desk” rather than in an office. “People get to know me and tell me things they might not otherwise,” he explained.

Some chairs ask individual NEDs to take a special interest in specific areas by networking, talking with investors, and engaging with management. This can be particularly effective if the area aligns with the NED’s professional expertise. But this, too, must be done judiciously, lest the board member cross the line between oversight and management.

Step 3: Make sure the board includes members able to interpret the signals. The board must have the skills needed to detect and understand signals indicating a need for change. This is particularly important in complex businesses, which may require members with more technical skills. As one director observed, “The days of the board as a retirement club for the great and the good are numbered.” Indeed, a number of board members pointed out that in many businesses, the importance of new technologies and distribution channels suggests that at least some members should be younger, digitally savvy executives in the middle of their careers.

Over the past few years, boards have become much better at removing nonperformers. But few boards have shown a willingness to meet changed business circumstances by removing competent board members in order to rebalance the board’s skills. A word of caution, though: the rush to secure specific expertise can lead to the appointment of single-issue members, which may not always be wise. Alternatives include the judicious use of external board advisors or the appointment of an advisory committee.

It is also important to create an opportunity for directors to formulate and share concerns. Private NED sessions, informal board discussions, and board dinners can all help surface potential issues. Said one director, “You don’t have conversations about nagging doubts in the board meeting; you test them outside with other NEDs.”

To supplement their own skills, boards should actively solicit external perspectives. For example, many chairs bring industry analysts, investors, consultants, members of the media, or other industry observers into the boardroom to offer their view of the issues facing the company. One board we looked at has a deeply experienced senior external advisor on a retainer—independent of management or board—with a “license to roam” anywhere in the business, something board members are not free to do. Such an advisor can be a valuable means of identifying issues and flagging them to management and the board. A small number of companies in our interview sample have established board-level external advisory groups typically focused on technology issues.

Step 4: Act on the signals. Normally the next course of action would be for management to take the board’s input and act accordingly. But if that is unlikely, the board must be willing to make difficult decisions, including replacing the company’s leaders. The board needs to ask whether it trusts management to deliver the necessary change. But replacing a company’s leadership is not straightforward, and it requires courage. “Getting rid of a perceived star CEO is one of the hardest things to do,” said one director. “Investors won’t thank you for it.” It is even harder in those jurisdictions where the roles of CEO and chair are commonly held by the same individual.

A board that includes members who have successfully managed major change in their own careers can help shape a productive dialogue with management. Rather than focusing on the risk of taking action, such a board can engage more confidently in discussions about the route forward and the risks of doing nothing.

Step 5: Take a disaggregated view of the business. Today’s businesses are increasingly complex. Challenges and risks get hidden within multiple geographies and business units. Directors must take a disaggregated view of the business rather than drawing comfort from a positive consolidated picture.

At one company, for example, directors become involved with management at specific locations, visiting regularly and developing relationships. This allows them to both provide support and improve their understanding of individual businesses. But again, clarity about roles is needed. The risk here is that board members will be co-opted by management and become advocates for particular parts of the business.

The Adaptable Board as an Agent of Change

Many boards see execution as management’s job. While that is true, boards have a responsibility to both oversee and support management to ensure success—especially when the company’s future health depends on effective change.

Change comes in many forms. It can be reactive (in the face of declining performance, for example) or forward looking (such as when global expansion or technological change is planned). More than 60% of large-scale transformations fail to achieve their goals, primarily because of failures in scoping and execution. At a minimum, a board needs to ensure that management has the following in place:

- The right plans

- The appropriate executives with the right capabilities to execute successfully

- The means to monitor plans effectively

- The ability to draw on the right expertise from beyond the executive team

Boards need to be adaptable, adjusting how they operate in response to the changing demands of the business. This may involve changing the intensity of the board’s work within the existing governance framework: more frequent meetings, more of the agenda focused on change, and more targeted reporting. For example, during one company’s period of change, the chair inverted the board’s agenda, leaving the minutes and standard reports or governance items to the end and starting with the most commercially important matters, in order to ensure sufficient time to discuss these critical issues.

Boards can also consider more fundamental changes:

- Altering Their Composition. The board’s makeup can be adjusted to reflect changing business needs. But it’s always important to question whether specific expertise is best delivered through a board appointment or the intelligent use of advisors.

- Refocusing Committees. Risk committees may need to adjust the balance between tactical risk oversight and a longer-term, strategic approach to risk.

- Being Flexible About Sources of Advice. The board can consider setting up an advisory board or bringing in independent experts for support.

- Adjusting Roles. Depending on circumstances, chairs may need to move from an advisory style to a more hands-on, challenging, even directive mode.

In our study, we also asked board members what the boards of public companies could learn from the boards of well-run private equity–owned companies. Their suggestions included finding ways to focus on value, getting more expertise into the boardroom, looking beyond the near term, and devoting more time to business issues. (See “Lessons from Private Equity.”)

LESSONS FROM PRIVATE EQUITY

When we asked board members what public-company boards could learn from the boards of well-run private equity–owned companies—and after allowing for the fact that not all lessons are equally transferrable—a number of insights emerged.

- Focus on Value. Private equity–owned company boards benefit from having shareholders in the room. Other boards can replicate some of these benefits by making sure that they always think like owners and by periodically inviting investors or analysts to provide insight into how shareholders see the company. Some board members see merit in all directors owning shares, though only at levels that do not compromise their independence.

- Experts on the Board. The boards of private equity–owned companies typically include experts with deep industry experience. Unlike public companies, these companies are not constrained by rules about “independence,” so they are able to appoint board members solely on the basis of their ability to add value. Likewise in contrast to public companies, private equity–owned company boards can address their expertise requirements at short notice. They are also free to invite external experts to either advise the board or participate in an advisory committee.

- Longer Time Horizons. Because they are not under pressure from short-term external investors, the boards of private equity–owned companies are often willing to invest to create value tomorrow at a cost today—at least in the early stages of ownership. Publicly listed companies should consider how they can build the case for investment and communicate it consistently to shareholders.

- Faster Pace. Private equity boards tend to meet more frequently and make decisions more quickly. During periods of change, the boards of publicly listed companies should consider whether the cadence of their formal board meetings is satisfying the needs of the business. It is extraordinary that the frequency and duration of public-company board meetings seem to be determined more by national culture and habit than by the needs of the business!

- Fewer Distractions. Private equity is free of some of the governance, investor relations, and remuneration battles typical of public companies. This allows them to focus on value. The boards of publicly listed companies should consider the role of committees and how they can delegate tasks in order to make time to discuss the issues that shape long-term success. Many of our interviewees called out the disproportionate amount of time devoted to executive remuneration at the expense of other business-critical items on the agenda.

Taking a More Nuanced View of Independence

Board members have decades of experience to deploy in order to add value to the company. During periods of change, there are a number of ways for directors to provide increased support to management while maintaining the appropriate distinction between management and oversight:

- Establish special committees to oversee change. One company set up a temporary board committee to support a transformation. The committee, comprising four NEDs, met with management every two weeks to test the emerging strategy. Its members were explicitly positioned as thought partners, deploying their experience to help management refine its approach.

- Assign directors to areas of special interest. At another company, directors were assigned to each of the company’s strategic priorities. In addition to developing a deep understanding of these areas of special interest, the directors were responsible for building a value-adding relationship with the respective executives in charge and then reporting back to the board. The arrangement had the twin benefits of leveraging the expertise of directors to support management and identifying quickly where implementation was not progressing satisfactorily.

- Implement informal coaching. Directors can provide support, advice, and coaching to members of the executive team. This is particularly common in the technology space. For example, a director with an extensive IT background at a global tech company coaches the CTO and meets with the IT team three or four times annually to discuss progress and offer advice.

- Provide “air cover” during periods of change. Boards can manage relationships with investors and communicate change to the wider world of stakeholders. In a company that was undergoing a hostile takeover, the chair took responsibility for both negotiating with the other party and communicating with shareholders, allowing the CEO to focus on managing the business.

Getting Started: Creating More Effective Board Engagement

An actively engaged board provides the building blocks of good governance. Directors with deep knowledge of the business and the external environment are better equipped to offer advice, challenge management, and spot any warning signs. But creating a more engaged board is neither easy nor without risk. While an actively engaged board can be a great benefit to a company, an engaged board that is dysfunctional can be destructive. If the board’s operating model is not right, and if the directors are not aligned, the board can undermine management and create confusion.Chair, CEO, and NEDs all have a role to play.

The Chair. The starting point is for the chair to lead the board in a discussion of its mandate: its purpose, its scope, and its operating model. By doing the following, the chair can encourage directors to become more engaged.

- Create a board culture in which concerns can be raised and discussed and productive lessons can be learned from failure. It helps if the chair works with the board to agree on a shared sense of purpose and to clarify the board’s mandate and operating model.

- Regularly review the board’s processes and agenda, and refocus committees to give the board more time for value-adding discussions.

- Set the expectation that directors will play a more engaged role, partly by agreeing to a board mandate encouraging greater interaction with management and staff, and partly by assigning directors with specific domain expertise to coach or mentor individual executives. This requires maintaining a fine balance. The chair has to make sure that the more actively engaged directors are not undermining executive accountabilities—and the CEO will know almost instantly if directors are overstepping. The chair and the CEO must therefore be sure to keep open the lines of communication between them and agree in advance to talk about and deal with this issue if it should ever arise.

- Leverage the periodic board-effectiveness process to develop customized support for individual directors, with a focus on ensuring effective contributions.

- Actively manage board composition in the context of evolving business needs—even if it means replacing directors who are performing well in order to appoint ones with newly required experience.

The CEO. While the CEO needs the support of the board to survive, it is also true that the board cannot be successful without the assistance of the CEO and the management team. CEOs need to ensure that the board has the information it needs to be engaged. They should also encourage management to take advantage of the more actively engaged board.

- Improve the quality of the information available to the board, such as through better use of portals and scorecards.

- Work with the chair to identify how the experience of individual NEDs could support the business.

- Make sure management understands the mandate of the board.

- Create opportunities for a broader cohort of management to gain exposure to the board.

- Encourage management to embrace a spirit of openness, receptivity, and curiosity when engaging with the board and with individual directors.

The NEDs. NEDs need to prioritize their scarce time. They should invest more of that time in building a deeper knowledge of the business and the wider industry context.

- Become more familiar with the business through site visits and conversations with staff.

- Leverage their personal and business networks to understand how outsiders view the company.

- Be prepared to have the difficult conversations that many boards avoid.

Always ensure that their behavior as NEDs doesn’t undermine the executive structure.

Chairs and boards operate in different ways. Many see it as a failure of management if the board has to trigger substantial change. But the board can support management by asking the right questions. The board can help identify and interpret weak signals. Otherwise, what is the point of all that accumulated board experience?