Employee engagement is a critical indicator of a company’s success. Engaged employees feel a bond with their company, are proud to work there, and take steps to improve the company’s prospects. However, BCG’s latest research shows that some of the world’s biggest and best-known companies have lower engagement than they should among senior-level women. This creates two problems. First, research has shown that companies whose employees aren’t engaged have weaker financial performance. Compounding this outcome, if promising women leave, companies could pay an additional financial penalty for having a less diverse leadership team. (See Shattering the Glass Ceiling , BCG Focus, August 2012.)

Our analysis of the factors that contribute to engagement among approximately 345,000 individuals reveals the scope of the issue. It also suggests how companies can respond. By rewriting the rules for how employees interact with each other and with management, fostering peer-to-peer connections, and making leaders accountable for results, companies can create a more engaging environment—not only for senior-level women but for all employees.

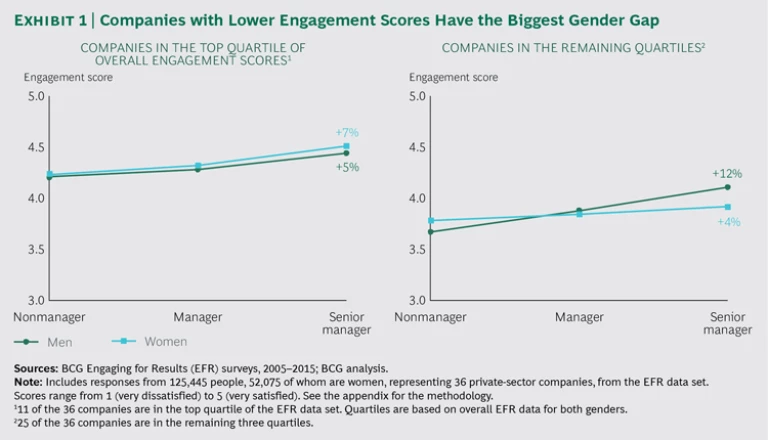

A Growing Gender Gap in Engagement

Among both men and women, engagement typically increases with rising seniority. As people take on greater responsibility and have more direct interaction with the C-suite, they tend to become more engaged. Our data shows that companies with the highest overall engagement scores (those in the top quartile)

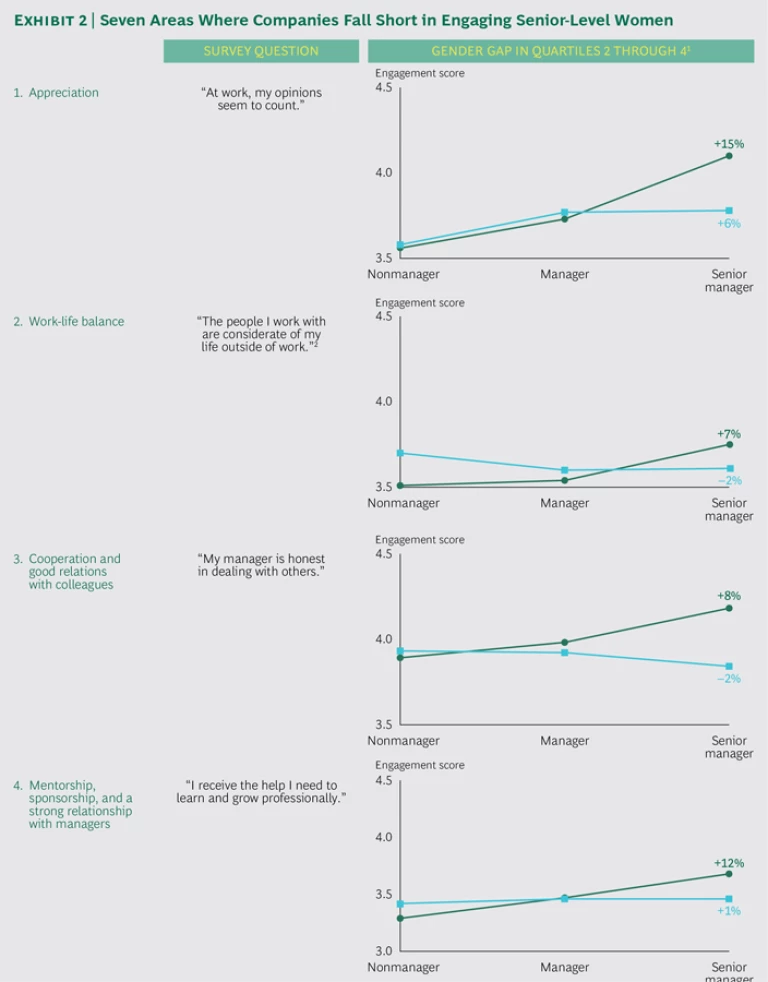

The data we’ve collected on seven areas critical to employee engagement highlights the problem. We have ranked these areas on the basis of their relative importance among the employees we surveyed. For all seven areas, our findings focus primarily on the companies with lower overall engagement scores (those in the second, third, and fourth quartiles). (See Exhibit 2.)

1. Appreciation. Women cite appreciation for their work from their superiors as the top criterion they look for in a job—as do men. In lower-engagement companies, senior women report feeling less appreciated. On questions concerning whether their opinions count and whether managers recognize and comment when they do good work, senior women’s scores are considerably lower than those of their male peers.

2. Work-Life Balance. Work-life balance or flexibility is the second-most-important factor for both women and men. As men rise in seniority, they report more support from their colleagues for their nonwork obligations, while women report the opposite. To look more closely at this discrepancy, we partnered with InHerSight, a US-based website that solicits ratings from employees about their employers. The data is clear: even the best programs will not improve engagement if they don’t offer what employees want. Flexible working hours and paid time off rate relatively high (roughly 3.1 out of 5); other work-life-balance programs—such as maternity and adoptive leave, family growth support, and wellness initiatives—rate lower (roughly 2.6). This data is US-focused, but BCG’s global data points to similar conclusions: companies seeking to improve employees’ work-life balance can do better. As always, the devil is in the details. Even the best programs will not improve engagement if companies don’t get the implementation right.

3. Cooperation and Good Relations with Colleagues. Women and men alike cite a strong relationship with colleagues as the third-most-important factor. Again, we see troubling results for senior women in the lower-engagement companies. They are more skeptical about whether their managers behave honestly with them and with others. And they report lower scores than senior men on the question of whether “people in my department trust and support each other” and whether “processes make it easy to work well with other departments.” In contrast, men’s scores in these areas increase markedly with seniority.

4. Mentorship, Sponsorship, and a Strong Relationship with Managers. Junior women in all companies report a positive experience with mentoring. Senior women at lower-engagement companies are less satisfied. In terms of receiving help with their professional growth, women’s scores remain flat as they increase in seniority, even as men’s scores rise steadily. When asked whether “my manager is a good mentor to me,” men’s positive responses increase with rising seniority twice as fast as women’s do. The pattern is the same for trust—a key component of mentorship and sponsorship. Senior women’s ratings fall behind those of men in areas such as “my manager cares about my well-being” and “my manager is open to receiving feedback from me.”

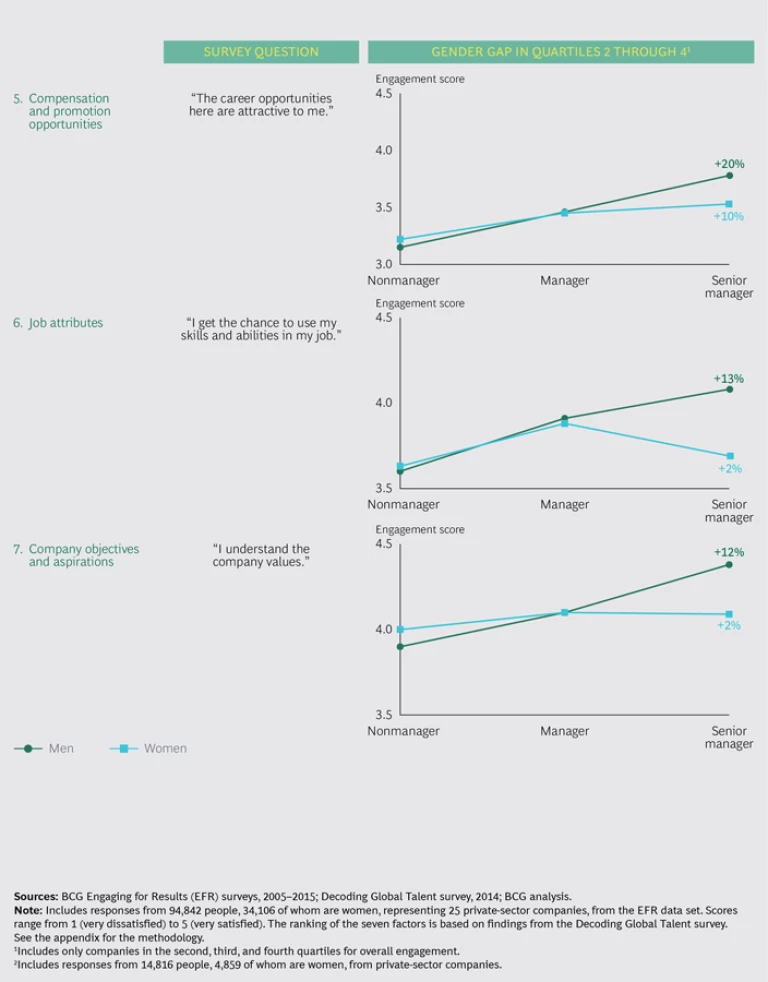

5. Compensation and Promotion Opportunities. Women want good pay, and, like men, they expect pay to be correlated with performance. Junior women are as confident as their male peers—or slightly more so—that their compensation accurately reflects performance. But this confidence rises less quickly for women as their seniority increases than it does for men. Even more concerning, men’s scores on the topic of “teams that perform well are recognized for it” rise three times as fast with seniority as women’s do. (See “How Gap Created Equal Pay for Women.”)

HOW GAP CREATED EQUAL PAY FOR WOMEN

Gap has long been a pioneer in gender diversity. Cofounder Doris Fisher was one of the first women to lead a multibillion-dollar company in the US. The company takes a wide-ranging view of diversity, using a culture of equality and inclusion as a way to attract top talent, advance women’s representation globally, increase employee engagement and retention, and improve business results.

In 2014, Gap launched Women and Opportunity, a global initiative to align all efforts related to women, including female employees, customers, and supply chain workers, and women in the communities where the company operates.

That same year, Gap made history as the first Fortune 500 company to validate and publicly disclose that it pays women and men equally for equal work. This accomplishment was no accident but a result of a new system of regular pay reviews—including mechanisms to correct disparities.

The pay reviews include four critical components:

- Provide market-based pay ranges to managers that are updated annually.

- Instruct managers to base decisions about employees’ pay on objective factors.

- Review pay relative to both the market-based pay range and internal peers (through a joint twice-a-year process between HR and business managers).

- Set aside money in the budget each year for promotions and equity increases that can be used to address disparities.

The system of pay reviews had strong leadership support from the board, the CEO, and other executives. Transparent metrics allowed the company to identify where it needed to make changes, while transparency about the overall initiative helped involve the entire company in the effort. As Eva Sage-Gavin, executive vice president of HR and corporate affairs at Gap during much of this period, put it, “Accountability and collaboration were key. We saw the opportunity to lead, and we made change happen together.”

6. Job Attributes. Both genders attach great importance to job attributes, and statistical evidence shows that job attributes have some of the strongest correlations with overall engagement levels. On average, senior women report feeling underleveraged as leaders, as demonstrated by their scores on the topic of “getting the chance to use my skills and abilities,” while senior men are less likely to feel that way.

7. Company Objectives and Aspirations. A company’s objectives, values, and aspirations matter: studies show that overall engagement is heavily influenced by this dimension. Among nonmanagers, junior women tend to feel positive about their connection to their company’s objectives and aspirations, but senior women are less positive than their male counterparts on this critical dimension. Similarly, junior women give comparatively high scores to questions about whether they “know what’s going on at the company,” “understand the company values,” and feel that there are “clear consequences for people who act against [them].” Senior women are less convinced.

Solutions to Implement Starting Today

Companies should start by understanding the root causes of their engagement issues, in particular by listening carefully to senior women. This is the most critical step, and one that companies often miss in their rush to move directly to implementing solutions. Yet the root cause of disengagement varies. In some companies, we have seen a vicious cycle in which women’s skills and opinions are not used sufficiently, leading them to disengage. Other companies have found that they are not active enough in promoting women on the basis of their potential. Instead, they wait for female employees to demonstrate strong performance in a given role, an approach that causes companies to miss out on their highest-potential leaders. Still others have found that senior managers in siloed business units are forced to rely on informal networks to get things done, a situation that can be disproportionately detrimental for women. Getting to the specific root causes for each company is vital to determine the right solutions.

Among the solutions to improve overall staff engagement—and to increase the engagement of senior women in particular—several steps should be priorities.

Rewrite the Rules. For company leaders, success requires going beyond recognition programs to redefine how performance is assessed and to rethink how to communicate appreciation for a job well done. This should involve ensuring that recognition links to concrete rewards or progression for all staff, including senior women, and implementing a feedback system that emphasizes strengths as well as weaknesses.

For example, in 2010, BCG found that women at the firm had lower levels of job satisfaction than men. As a result, disproportionate numbers of top-performing women were leaving. After conducting in-depth research into the underlying causes, BCG found that the biggest factor in job satisfaction for women was the day-to-day apprenticeship experience. Apprenticeship is particularly important at BCG, where junior employees learn by doing.

Male and female employees at BCG reported that the feedback they received often focused too much on what they needed to do better and not enough on what they already were doing well. In response, the firm began to make meaningful changes in its apprenticeship model, launching a program known as Apprenticeship in Action (AiA), which it developed in conjunction with BRANDspeak, a leadership development consultancy. Since the program was rolled out across North America about two years ago, retention and job satisfaction among women have improved significantly. Employees of both genders are also about 10 percentage points more likely to say they receive the right amount of constructive feedback (including tough messages).

How did the firm achieve these gains? In large part by focusing on strengths-based development. Rather than providing mostly vague generalities, feedback is now highly detailed and grounded in specific actions and real-world examples. In addition, for each employee, managers prioritize two or three concrete areas for improvement that are linked explicitly to the employee’s strengths. This provides a solid foundation on which to build. And although AiA was launched in response to issues among women, male employees have benefited as well.

In addition to emphasizing employees’ strengths, companies should provide flexible work models to women and men at all levels, ensuring that part-time work is a viable option for everyone (not only for new mothers). And they must manage performance effectively to ensure that people can legitimately succeed in these programs. Output-based KPIs (for instance, assessing whether the work gets done, not where it gets done) can help. It’s also important to allow managers to move into more flexible roles for a defined period, particularly after several years of long or inflexible hours.

Leaders should ensure that there is no gender-based pay gap and that compensation processes are transparent. It helps to mandate a regular pay review and track for bias in both outputs (pay) and inputs (evaluation scores or qualitative feedback, depending on the system).

Finally, companies should give senior managers the latitude to shape their job responsibilities (within limits) so that they can focus more on their expertise, passions, and interests. (See “GSK Helps Employees Reengage by Pursuing Their Passions.”) Performance management systems must be flexible enough to adjust to individual development and career paths. Companies need to embrace different leadership styles and be prepared to promote senior women to key roles on the basis of their potential, not just their performance. Creatively considering the attributes needed for the most senior jobs can reveal if a different set of skills could bring benefits. Companies can also consider developing matrix responsibilities that enable senior women to participate in prestigious content- or expertise-driven initiatives.

GSK HELPS EMPLOYEES REENGAGE BY PURSUING THEIR PASSIONS

In 2009, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) created an innovative program that allows employees to work at nonprofits aligned with the company’s mission. Called PULSE Volunteer Partnership, the program has placed more than 635 employees with more than 100 nonprofits over the past seven years.

Beverley Jewell is a good example. As head of global commercial operations for GSK Vaccines, she helps the company develop, produce, and distribute over 1.9 million vaccines daily to people in more than 150 countries. But as the strategic demands of her job grew, Jewell, a trained scientist, recognized that she was struggling to stay engaged.

“A key reason,” she says, “was a disconnection between what I do day-to-day—where I’m focused on long-term global business goals and strategy—and the impact this has on developing medicine for the patient, which is why I went into pharmaceuticals in the first place.”

She took advantage of the PULSE program to take a break from her job and spend six months in Kenya working full-time for Amref Health Africa, a leading nonprofit in the region. During this stint, she helped the organization’s medical outreach program, which arranges for doctors from large urban teaching hospitals to perform basic surgery in remote rural areas.

“PULSE gave me a fantastic opportunity to reconnect with why I loved my career in the first place,” Jewell says. “I didn’t realize the depth and breadth of skills I’d learned at the company until applying them in this new environment.” She was so transformed by the experience that after she returned to work at GSK, she continued volunteering with Amref in its London office one Friday every month, on her own time.

The experience has also helped her reengage with her work. That’s a common result. Of the employees who participated in the program in 2015, 91% said the experience changed the way they work, spurring them to do more with less and become more culturally agile. Most important, 74% of participants said they returned with reinvigorated energy, spirit, and motivation—the cornerstones of engagement.

Support Peer-to-Peer Connections. Boosting connections among peers can lead to greater appreciation for contributions from employees and managers—both men and women. To that end, companies should increase the proportion of shared (instead of individual) goals that managers must meet so that it’s in their interest to cooperate across business units and functions. Organizations can help leaders hired from the outside to build their own networks. Leaders should penalize the failure to seek or provide help by requiring employees to flag issues as or before they arise. And performance reviews should give less weight to failures as long as employees sought adequate and timely help from the right people across the company.

Consider the experiences of a European company that analyzed its value chain and found that it was struggling in two areas: developing more innovative products and getting them to market faster. This was causing frustration and disengagement at the company among both men and women. By looking more closely, the company found that key stakeholders weren’t cooperating, for several reasons.

First, people were typically promoted primarily on the basis of individual achievements (“being a hero”) rather than team objectives. Second, the company promoted people rapidly, sometimes after just 18 months in a role, so they often weren’t in a position long enough to feel the consequences of not cooperating. Last, many people were involved in making and approving decisions, which slowed the process of getting innovative products designed and onto store shelves. Teams tended to blame the obstructive mindset of other teams for these problems, and people pointed to nationality, gender, or other stereotypes to explain others’ lack of cooperation. In fact, everyone was behaving entirely rationally given the context, but the end result was unnecessary bureaucracy and friction.

To improve, the company has applied Smart Simplicity—an approach BCG developed to help companies foster cooperation and deal with complexity. (See “ Why Managers Need the Six Simple Rules ,” BCG article, March 2014.) Specifically, the company has taken the following steps:

- First, it has identified a diverse group of “integrators”: people who know the most about developing innovative products and getting them to market, and have the incentives to succeed and the power to make things happen.

- Second, the company has identified target behaviors for the integrators. In an ideal world, what could or should these people do differently? Through that exercise, the company has begun to rewire its ways of working together, creating a context that helps integrators willingly adopt the new behaviors.

- Third, the company has extended the amount of time that people remain in their roles and has forged cross-business-unit promotion paths. Those moves have created feedback loops that ensure individuals feel the consequences of their actions.

The company is still in the early stages of this effort, but already it is seeing gains.

Hold Leaders Accountable for Results. For all these measures, companies should put in place structures that allow senior executives to gauge performance, report results, provide incentives, and hold themselves accountable for improvements. The following steps are crucial parts of this effort:

- Make sponsorship a formal part of the performance review for senior leaders, going beyond basic “check the box” efforts to include genuine connections and loyalty. (See “At Sodexo, Mentorship Programs Boost Engagement Among Women.”) Overinvest in sponsorship connections with promising female employees. Tell these women that they are considered to be high-potential, and ensure that they have mentors, sponsors, and peers with whom they can partner.

AT SODEXO, MENTORSHIP PROGRAMS BOOST ENGAGEMENT AMONG WOMEN

French food services and facilities management company Sodexo is globally recognized for its commitment to diversity. Sodexo’s success is the result of more than a decade of work, starting when the company hired its first chief diversity officer, Rohini Anand, in 2002. When she arrived, the engagement gap between women and men was “startling,” as Anand put it. Today, women’s engagement in some cases even surpasses that of their male colleagues.

To close the engagement gap, the company took decisive steps to promote a more open and inclusive corporate culture. Sodexo also launched mentorship programs at all levels, many targeting high-potential women and focused on operational roles. For example, promising junior women are offered networking opportunities and exposure to female leaders through virtual webinars. At higher levels, the company’s gender advisory group, called Sodexo’s Women International Forum for talent (SWIFt), consists of senior leaders who set the company’s global gender strategy and mentor rising talent. Employees who take part in SWIFt—both men and women—get significant access to Sodexo’s top leadership.

The company also focuses on mentoring and developing managers at the midpoint of their careers, a time when some women step off the operational leadership track. The company identifies high-potential managers through a rigorous process that includes ratings and manager reviews, and employees must formally apply to join the mentoring program. “It’s a high-touch process,” says Anand, “but that level of people investment is part of our culture.” Sodexo’s goal is for women to constitute 60% of participants. Selected employees get matched to senior mentors, who are chosen through a similarly rigorous process and trained in good mentorship practices. The program matches people across business lines to ensure broad exposure for mentees. Most important, it works: women in the program are promoted significantly faster than their peers.

Among the company’s US employees, women’s engagement levels are on par with men’s, and 87% of women say that they are satisfied with the company’s diversity efforts. Sodexo’s research shows that diversity is a key factor in overall engagement.

- Include quantitatively validated pay metrics in KPI dashboards to keep compensation on the agenda of senior leaders.

- Align the executive team on the company’s vision, values, and goals, and ensure that senior managers, including the top executive team, are truly living the values and goals and communicating them across the organization. For example, during cost-cutting periods, ensure that senior leaders manage their own business expenses with the same rigor that they expect from others.

Consider SunTrust Banks. The company focuses on improving the financial well-being of its clients. Yet when it conducted its annual employee engagement survey in 2013, only about a third of the workforce agreed with the statement “I’m in the financial shape I want to be in right now.”

In response, SunTrust developed the Financial Fitness Program for Teammates, which is designed to help employees and their families set and achieve realistic financial goals. Of those who completed the program, 75% reported feeling more confident and in control of their finances. Follow-up surveys found that 82% of participants believe that SunTrust cares about them, and 74% feel that they’re on the path to greater financial well-being.

The results are clear: when a company applies its purpose to its own employees, it can increase their well-being and boost retention. “People want to work for companies that stand for a greater good,” says Susan Somersille Johnson, the company’s corporate executive vice president and chief marketing officer.

Senior-level women want to be paid well, enjoy their work, feel connected, express their opinions, and see that senior executives are living the company’s values. By taking steps to improve in these areas, companies can increase the success and happiness of women in senior management positions and promote more women into the C-suite—a move that will increase overall staff engagement. Helping women become more engaged at work is not just good for women; our research shows that it is good for everyone.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following BCG colleagues for their contribution to this publication: Susanne Dyrchs, Grant Freeland, Federico Fregni, Anna Green, Jim Hemerling, Leila Hoteit, Iván Martén, Dolly Meese, Antonella Mei-Pochtler, Stéphanie Mingardon, Renata Moniaga, Yves Morieux, Nina Morton, Massimo Portincaso, Mai-Britt Poulsen, Vaishali Rastogi, Julia Reichert, Joseph Reiman, Jaime Rooney, Michelle Russell, Eva Sage-Gavin, Margaret Schear, Frances Taplett, Roselinde Torres, and Judith Wallenstein.

In addition, they would like to thank their external collaborators: Dan Henkle and Bobbi Silten, at Gap; Liz Burton, Jayne Haines, and Kalpesh Joshi, at GSK; Ursula Mead, at InHerSight; Rohini Anand, at Sodexo, and Michael Montelongo, formerly at Sodexo; and Susan Somersille Johnson, Sue Mallino, Miguel Sepulveda, and Suzanne Vincent, at SunTrust.