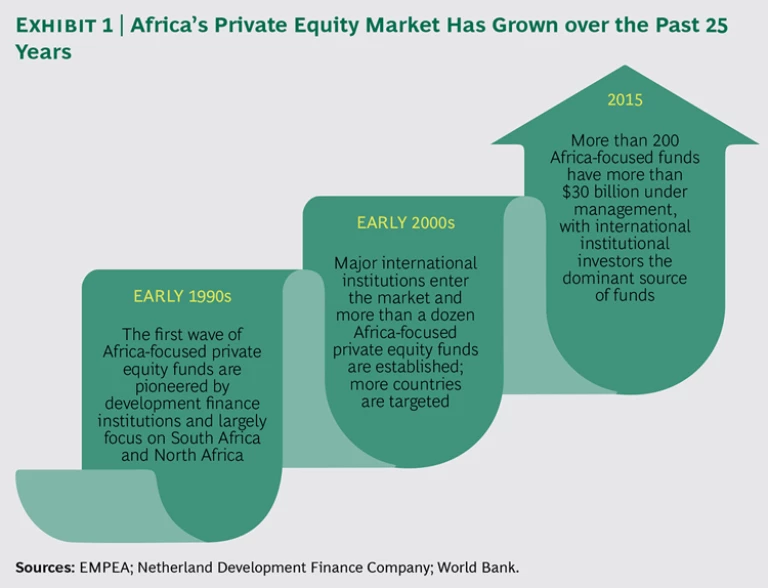

For the past decade, Africa has been one of the world’s hottest growth markets for private equity investment. In the early 1990s, a mere dozen Africa-based funds managed a combined $1 billion; today, more than 200 funds manage upwards of $30 billion. More funds are making more deals in more industries and more countries—and are making more successful exits. The expectations of investors in private equity funds are also rising as development finance institutions are being joined by global institutional investors that are far more focused on high returns.

Is Africa’s private equity boom really being driven by economic fundamentals? Or is a bubble building? In the view of some analysts, the growth has come too fast. Too much money is chasing too few sound investments, they fear, pushing up prices of African corporate assets. What’s more, the surge of capital is coming just as a sharp downturn in commodity prices has slowed economic growth across the continent, reigniting fears of currency devaluations and dividend repatriation.

We believe that these concerns are understandable. But they are not the right concerns. It is true that many resource-dependent African economies have entered a period of economic uncertainty after a decade of robust growth. Yet the continent has economic strengths that should continue to present attractive growth opportunities for private equity for the foreseeable future. The region’s rapidly expanding companies can absorb immense foreign investment and generate high returns for investors. Another driver: Africa has tremendous needs for private capital to fund its continued growth. To fully capture this opportunity, however, investors need to broaden their investment approach.

Cast a Wider Net

Too many private equity investors are pursuing the same kind of target with the same kind of deal structure. Overwhelmingly, both major international and local funds are focusing on Africa’s limited pool of large, profitable companies that have proven track records of sound management and the potential to grow regionally or even internationally. Most funds are looking for minority positions in these companies.

Such strategies have worked well for many funds and will continue to deliver strong returns for some of them. But the market for such deals is getting crowded, driving valuations up and returns down. To earn high returns in Africa’s rapidly evolving landscape, fund managers must pursue alternative investment strategies that include segments currently underserved by private equity.

Look beyond the narrow cohort of the continent’s corporate elite and you’ll see that Africa is awash in opportunity. Dynamic small and midsize companies are emerging as national leaders. Many startups are building innovative, disruptive business models and leveraging digital technologies. Established family-owned enterprises now led by a new generation of well-educated managers are seeking capital to expand. And attractive, high-potential assets are sitting on the books of diversified companies that no longer regard those holdings as core to their business. The challenge for private equity funds is to identify these targets and make the deals happen.

The private equity industry needs to consider more-flexible African investment strategies and expand its offerings to the continent’s companies. Funds should consider such options as investing in majority stakes and strategic partnerships. They should also consider offering evergreen funds rather than only funds with timing constraints for divestiture. In more-developed economies, private equity funds still reap a significant portion of their returns through financial restructuring and improving the bottom line with better management. In Africa, by contrast, funds are more likely to achieve high yields by investing in companies with sound industrial and development plans, such as expansion in new markets, and by reinforcing management. Controlling stakes may put investors in a more powerful position to add value to their acquisitions and provide more options to sell assets.

By adapting their investment approaches to Africa’s evolving environment, private equity funds will be better aligned with the major structural changes underway on the continent. One such change is the growing role of global institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurers, as the chief investors in Africa-focused funds. This shift in the market will dramatically change the way the private equity industry approaches the continent. While development finance institutions certainly seek profitable investments, they also have a mission to advance the development of industries. Institutional investors, by contrast, seek maximum returns.

Making the transition needed to fulfill these expectations for higher returns will not be easy. Not all funds have the capabilities in local African markets to identify and address small targets and other new types of opportunities. Because reliable information and the intermediaries that typically bring them deals are still scarce in Africa, funds must establish a strong on-the-ground presence in a number of markets to originate deals and perform due diligence. Even if funds have experienced managers, local technical and investment expertise will become more critical. As they invest in smaller companies and take more majority positions, funds will also need to be able to help companies accelerate their growth and create significant value. There is also a big need in Africa for smaller, sophisticated, and more specialized funds with strong local expertise that can help prepare the field for strategic buyers and larger funds.

The Evolution of African Private Equity

Development institutions such as the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) pioneered private equity investment in Africa in the early 1990s. Their mandates still include the promotion of economic and industrial development, so these institutions are willing to take greater risks and expect lower returns than traditional investment funds, which are measured solely on returns. Mired in economic stagnation for decades, the continent has long been almost completely off the radar of the world’s leading investors.

Africa’s emergence from that prolonged period of stagnation to become one of the world’s next great growth markets has changed investors’ attitudes dramatically. (See Winning in Africa: From Trading Posts to Ecosystems , BCG report, January 2014.) From 2013 through 2015 alone, private equity funds mobilized $10 billion to invest in Africa and completed $14.8 billion in deals—more than double the level of the previous three years. The changes are bringing increased diversity on several fronts:

- Players. Many of the world’s largest private equity players are now active in Africa. A number of funds have dedicated African teams and funds or have opened offices on the continent. Carlyle Investment Management is managing a $698 million fund dedicated to sub-Saharan Africa. The Abraaj Group, based in Dubai, is deploying $1.8 billion across the continent. Helios Investment Partners is managing a total[--All of these figures are year-end 2015 estimates based on company websites and press reviews.--] of $2.3 billion.

- Investors. The sources of capital for Africa-focused private equity funds are changing as well. With the arrival of global funds, the development finance institutions that contributed to the first and second generation of African funds are giving way to more traditional, large institutional investors, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments. (See Exhibit 1.) Development finance institutions will continue to play a critical role for the industry development by sponsoring riskier, impact-focused projects. But as explained in this report, the expectations for these new institutional investors have important implications for the private equity industry.

- Targets. Another change in Africa is that private equity funds are investing in more diverse portfolios. At first, funds tended to target energy, banking, and commodities—sectors that were supported by development agencies. From 2007 through 2014, however, 57% of private equity investments were in companies selling goods and services to Africa’s growing consumer class, according to the African Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (AVCA). Indeed, 76% of private equity investors in a recent AVCA survey cited consumer products as one of the most attractive sectors for investment in Africa, compared with 46% who cited financial services. The share of deals involving private equity in M&A activity on the continent has also increased, rising to 22% of total activity in 2014 from less than 6% in 2012.

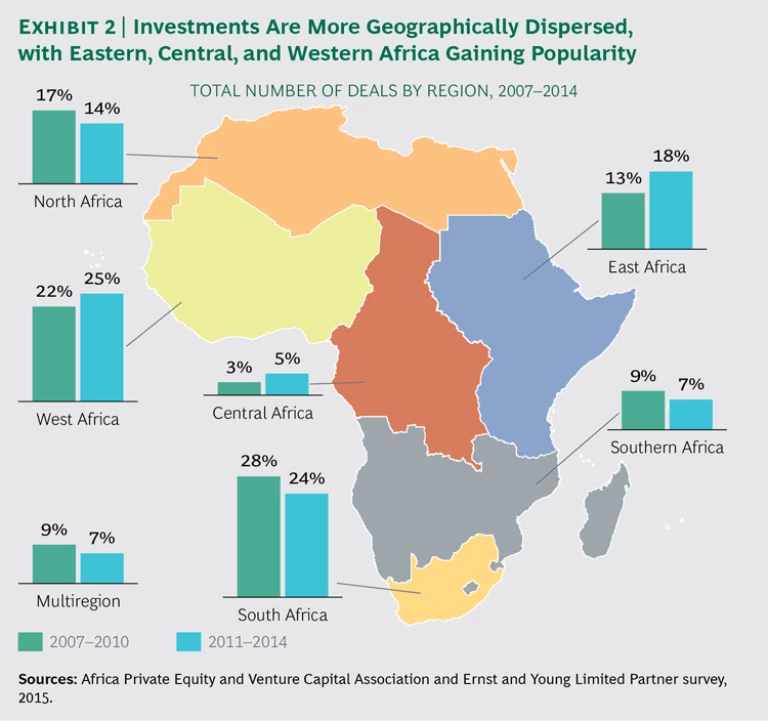

- Geography. Investors are diversifying geographically as well. From 2007 through 2010, 28% of deals were in South Africa. That dropped to 24% from 2011 through 2014. The portion of deals done in West, Central, and East Africa, meanwhile, rose from 38% to 48% over those two time periods. (See Exhibit 2.) In terms of value, South Africa’s share of African deals dropped to 15% on average from 2010 to 2015, according to AVCA, while East, Central, and West Africa captured 33% of total investment. Seventy percent of limited partners—the investors in private equity funds—surveyed by AVCA cited West Africa as the most attractive region for investment over the next few years.

One clear sign that Africa’s private equity market is maturing is the rising number of exits. The growing presence of large funds and principal investors is greatly broadening the market for African corporate assets, making it easier for existing investors to divest. An average of 40 exits by private equity funds was recorded in Africa in 2013, 2014, and 2015, compared with an average of 29 for the previous five years. What’s more, “secondary exits”—sales of companies or equity stakes by one fund to another—accounted for 23% of private equity asset sales in Africa in 2014. That was about the same proportion as in Europe and compares with an average of 14% over the previous six years.

Investors are confident that Africa remains a strong growth opportunity. Half of the global limited partners surveyed by AVCA in 2015 said they regard Africa as more attractive for private equity investment than other emerging and frontier markets. Ninety-one percent also said that they plan to either hold or increase their private equity allocations in Africa over the next few years.

Why the Bubble Worries Are Misplaced

The rapid increase in investment funds has raised concerns that a private equity bubble is emerging—essentially that too much money is chasing too few companies—and pushing the prices of available African assets to high levels.

The crash in global prices for the commodities upon which many African economies heavily depend has heightened this concern. Political events and a terrorist presence in several northern and central African nations have added to fears that the continent’s impressive economic revival over the past decade is in jeopardy.

The commodity downturn clearly has cooled African economies. Revenue from natural resources across the continent plunged from a high of $460 billion in 2008 to about $250 billion in 2014. Largely as a result, GDP growth in Africa slipped from almost 7% in 2012 to approximately 4% in 2014. The initial terms-of-trade deterioration is estimated at 18.3% for the continent in 2015, and several economies are close to recession in 2016.

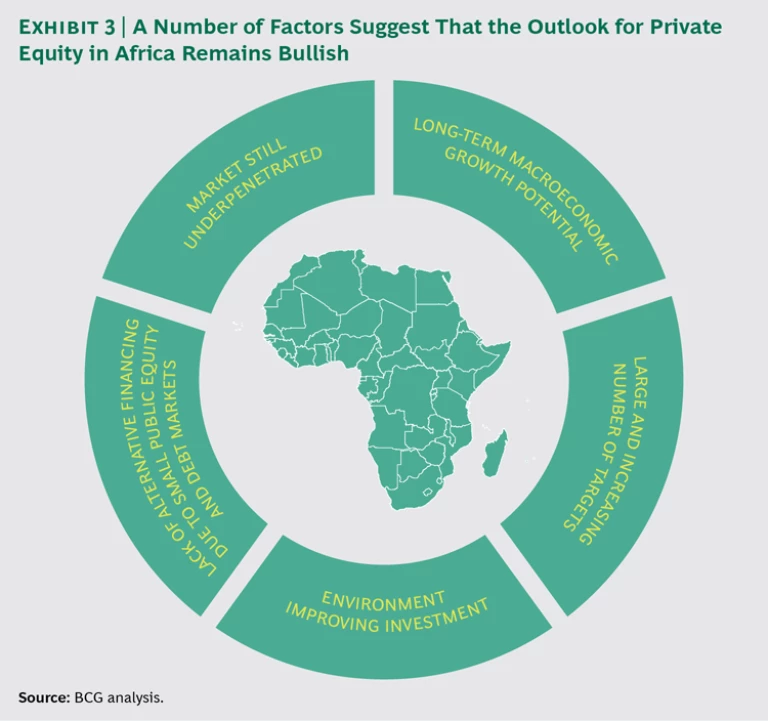

Despite these risks, we believe that Africa remains one of the world’s greatest growth opportunities for private equity. The following factors support this bullish outlook.

Private equity penetration is low. Despite rapid growth in recent years, the amount of private equity and principal investment capital mobilized in Africa remains very low relative to world standards. Private equity assets under management are approximately 1% of GDP in western countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, by contrast, private equity assets under management are a mere 0.1% of GDP. What’s more, even though Africa accounts for 3.1% of global GDP, only 0.9% of global private equity funds that are raised focus on the continent.

Africa’s macroeconomic fundamentals remain strong. Healthy economic growth in the decades ahead is likely to greatly expand Africa’s capacity to absorb private equity investment. The continent has enormous needs for physical infrastructure, and there are growing opportunities for large-scale investments in real estate, industry, and services. Although growth in aggregate real GDP in 2016 and 2017 is expected to remain well below the 5% annual average recorded from 2007 through 2014, most economists project that it will soon rebound to historical levels. Average growth of 6% to 9% is projected in economies such as CÔte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania.

Africa is one of the world’s fastest-growing destinations for foreign direct investment, particularly in sectors such as energy, transportation, and real estate. The continent’s working-age population is projected to keep climbing for another five decades. Africa’s skilled talent base is also expanding. The portion of college-age Africans enrolling in tertiary schools more than doubled, to 7%, between 1990 and 2010. What’s more, nearly 400,000 African students were studying in nations such as France, the UK, and the US as of 2010. A high percentage of this African diaspora expresses interest in returning home to work upon graduation.

Africa’s rapidly growing consumer class will be a powerful driver of growth. Household expenditure tripled across the continent from 2004 through 2013. The number of middle-class and affluent Africans, those with annual incomes of $1,600 or higher on a purchasing-power-parity basis, is projected to roughly double by 2024, to 166 million, and to reach 270 million by 2034. The continent is projected to add 50 million people with annual incomes of $8,400 to $20,400 over the next two decades and 17 million people with annual incomes exceeding $20,400.

The pool of investment targets is growing. Most funds focus on companies that are considered very large in Africa’s context—those with annual revenues of more than $100 million, assets of more than $200 million, and more than 1,000 employees. There are some 5,000 such companies on the continent, and their number is growing. Indeed, Africa is producing more companies that are competing successfully with multinational corporations and are expanding globally. (See Dueling with Lions: Playing the New Game of Business Success in Africa , BCG Focus, November 2015.)

However, there are nearly 11,000 African companies with revenues of $10 million to $100 million, assets of $20 million to $200 million, and staffs of at least 150. This is the fastest-growing segment of African targets—but it remains off the radar of most large private equity funds and principal investors.

The investment environment is improving. Despite the economic challenges and policy missteps in many African economies, the overall investment ecosystem is developing steadily across the region. As more private equity funds, investment banks, and institutional investors establish a local presence in more African economies, they are bringing expertise in a greater variety of deal structures and investment techniques. The pool of local lawyers, auditors, consultants, and bankers with private equity experience is also expanding. By the same token, more African companies are gaining experience in advanced finance.

Governance, too, is improving in many sub-Saharan African nations. CÔte d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo, Senegal, and the Democratic Republic of Congo rank among the nations that have improved corporate governance the most, according to the World Bank’s Doing Business 2014 report. The growth of regional and continent-wide professional associations is making the business environment more transparent. While political risk remains high on the continent, it is improving in many economies. A number of governments are becoming more business friendly.

Alternative options for raising capital are scarce. The difficulty that African companies face in raising capital from local equity and debt markets presents a big opportunity for private equity. Only four African economies—Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa—have stock exchanges with a market capitalization of more than $50 billion. In fact, the 29 stock exchanges on the continent have fewer than 2,000 listings combined.

The small scale of African equity markets makes it difficult for companies to raise the capital they need to grow—or for their founders to exit their business—through initial public offerings. There were only 28 IPOs in Africa in 2015, comprising approximately 2% of the more than 1,200 IPOs done globally. These IPOs raised a combined $12.7 billion (less than 1% of capital raised globally through IPOs)—which does not come close to bridging the financing gap in Africa.

The Shifting Private Equity Landscape

To unlock Africa’s potential, funds need to understand the changing dynamics of the continent’s private equity markets. The entry of new kinds of investors is transforming the market. Opportunities to invest in different kinds of target companies are opening. Successful funds are deploying different investment strategies. New intermediaries are opening offices. While the trends present opportunities, significant challenges remain.

The Changing Investor Profile. A new breed of investors in Africa-focused funds is changing the private equity landscape in fundamental ways. As private equity matures in Africa, the role of development finance institutions is diminishing, while more traditional limited partners, such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and endowments, are accounting for a greater share of private equity capital.

These new investors bring different expectations. The primary mission of development finance institutions such as IFC is to make an impact on an economy and to help develop private capital markets. Africa’s new institutional investors, by contrast, seek high returns—often much higher returns than they can expect in other markets. A recent survey by AVCA found that 52% of limited partners expect that private equity returns in Africa will be higher than in other emerging markets. Indeed, nearly half report that the performance of their African investments already has matched or exceeded their expectations.

New Investment Targets. Historically, private equity funds have focused on a very specific kind of investment in Africa. They have targeted big, profitable companies that dominate their local markets or are regional leaders. Private equity funds also want companies with proven track records of sound, enlightened management. The supply of such mature targets, however, is well short of demand in Africa. As the competition for these assets intensifies, achieving high returns grows more challenging.

Investors that broaden their horizons will find abundant investment targets. Great opportunities in Africa are with smaller companies that are growing fast—and have the potential to grow much further with infusions of outside capital and management help. For example, Africa has a number of what BCG calls local dynamos, which are rapidly growing companies that are bidding to become national leaders. (See 2014 BCG Local Dynamos: How Companies in Emerging Markets Are Winning at Home , BCG report, July 2014.)

The continent also features many established family-owned companies that are led by professional, second-generation managers, many of whom have been educated in the US and Europe. The private equity fund managers we have interviewed say that the new generation of family business leaders is more open than their elders to accepting outside capital and partners to modernize their operations and expand beyond their borders. A recent survey by PwC found that 24% of family businesses in Kenya, for example, prefer to raise capital from private equity, and that 37% plan to sell or float their companies, compared with a global average of 20%. There are also a significant number of family-owned businesses across Africa run by founders who wish to sell their companies, often because they are apprehensive about transferring their businesses to heirs they do not regard as having the skills or business aptitude to succeed.

Yet another rich source of opportunities consists of the holdings of established African companies seeking to shed assets that they no longer regard as core. Many of these opportunities lie in family businesses that used their cash over the years to diversify into businesses that have grown more competitive or that aspire to put their capital to better use in other sectors.

Different Investment Strategies. An additional distinct characteristic of Africa’s private equity market is that private equity funds prefer to acquire minority positions in a broad portfolio of holdings. When AVCA surveyed investors in 108 African deals, 80% of the respondents said that they invested via minority positions—compared with only 20% in developed economies. Given the high degree of volatility and the complex business environments in many African economies, fund managers maintain that minority stakes help manage risk. General partners who prefer minority stakes say that they feel more comfortable in Africa when they find the right kind of partner—one who knows the field and can manage the business day to day. They also say that it can be tough to find business owners who are willing to cede control unless they are under duress and that the scarcity of experienced executives in Africa makes it difficult to replace incumbent managers.

Some leading private equity funds are taking a different approach, however, and investing in more majority stakes. By exercising control, these managers say, they can better manage risk and create value because they can move more decisively. Controlling stakes also open more options for exiting because funds do not have to align with a majority investor. We found that the majority holdings of several significant private equity funds with both kinds of investments outperformed their minority holdings.

Funds can also explore evergreen investment structures. Currently, most funds are obligated to liquidate holdings and return capital to investors over a certain time frame. Evergreen funds, which have no fixed time frame, offer the flexibility to hold on to assets until it is the best time to sell and to roll the proceeds of divestitures into new investments.

As will be explained below, however, adopting a more active approach to creating value has several important implications. It often means that funds must hold their investments for longer periods of time and invest more resources in building an on-the-ground presence to manage companies in the portfolio. It also means that returns must be higher to justify the greater cost.

Africa’s Costly and Complex Investment Ecosystem. The investment ecosystem in Africa is not as well developed as that in the US and in Europe. Access to information is limited, and on-the-ground expertise is in short supply. Investors must navigate a wide variety of business cultures and customs and do business in many languages. This is why transactions in Africa often take 18 to 24 months to complete, far longer than in developed economies.

As a result of this incomplete ecosystem, operating successfully in Africa is costly and requires substantial investment to build local capabilities. Africa-focused private equity funds employ more staff than similarly sized funds elsewhere. The median employment level of international private equity funds is $112 million in assets under management for each staff member. For Africa-focused funds, the median is $45 million.

Most global investment banks still cover Africa from offices outside the continent. Only a few have operations in several African nations. Given investors’ scarce local presence, the number of intermediaries and sources of information is growing—leading consulting companies have recently started to open offices across Africa, for example. The number of African financial advisors and both international and African legal advisors with private equity experience is growing as well.

Still, the demand for such expertise outstrips the supply. For the time being, private equity funds must spend more time and money in Africa originating deals and performing due diligence on their own.

Winning in African Private Equity

Africa should remain one of the world’s greatest growth opportunities for private equity for decades to come. We believe that, to attain the high returns that investors expect given their perception of the continent’s risks, the industry will need to become more flexible. Funds should consider new kinds of investment targets and strategies. The winners are also likely to be firms that invest in the local capabilities needed to originate and assess deals and add value to their holdings.

We see some positive evolution in Africa’s private equity landscape. Funds are demonstrating a better understanding of local constraints, and a number have successfully adapted their investment strategies. Still, the industry requires another leap to better capture the potential. We suggest that private equity firms consider the following approaches.

Unlock new investment opportunities. Given the intense competition for Africa’s limited supply of big, mature, profitable, and professionally managed companies, many of the best opportunities on the continent lie with companies that are not traditional private equity targets. Funds should consider exploring fast-growing companies with disruptive business models, for example, and family businesses led by a new generation of management talent. Creating specialized funds with specific capabilities to address this potential might be necessary. Funds should also look further afield than South Africa and Nigeria, currently the two dominant markets.

Identifying and assessing high-potential targets takes more effort in Africa than in more mature markets, where investment banks and other intermediaries generally furnish such services. Given the continent’s current shortage of experienced intermediaries and reliable information, private equity firms will need to invest in building their own capability to originate and screen deals. They must also invest more time and resources to perform due diligence. The rewards of such efforts can be high. A study by AVCA found that general partners that conduct extensive due diligence on target companies and their management generate returns that are significantly higher than the average in Africa.

Consider diverse investment approaches. The strategy of managing risk by investing in minority stakes in a broad portfolio of African companies has worked well for many private equity funds. But the industry should consider alternative approaches. Doing more deals in which funds hold controlling stakes may be counterintuitive to the approach typically followed by a private equity fund in a market such as Africa. But majority strategies make it easier to manage market volatility and increase value creation by giving funds greater freedom to accelerate growth, execute M&As, bring in experienced managers and board members, introduce better corporate governance, and identify possible strategic buyers.

Funds should also consider being more flexible with regard to maturity periods for their investments. Most funds currently adhere to very strict timelines. They must divest an asset within five years, for example, regardless of the economic or business circumstances at the time. Because African markets tend to be volatile, time horizons should be less rigid. Funds may need to hold an investment for seven years, for example, to reap the full value of their investment. Or they may be able to take advantage of an ideal selling opportunity that arises a year earlier than expected.

Reinvent the exit strategy. Unlike in most mature economies, the options for divesting a holding in Africa are limited. Private equity funds must therefore begin to actively consider a realistic exit strategy from day one. Funds should identify potential buyers for African corporate assets before they even make the investment. They should analyze how a holding complements the development strategies of potential buyers and what will be required to make that asset attractive in the future. By planning a realistic exit strategy at the outset, funds can minimize the risk that they will find little appetite for their asset when it comes time to sell. In particular, by identifying potential buyers very early and then shaping the assets to better fit the buyer’s strategy and needs, funds could create true exit options for their investments.

Invest in building capabilities. Africa’s underdeveloped investment environment means that private equity firms need to build significant on-the-ground capabilities in Africa that they normally do not require in more developed markets.

The current shortage of investment banks and other middlemen that typically screen opportunities and bring them to investors means that funds often must be able to originate their own deals and perform their own due diligence. Some of the best-performing African funds have built these capabilities internally. They have invested in local offices and staff across the continent. They have hired people who intimately understand the local markets and have their own intelligence networks and personal contacts inside family businesses. Such capabilities cannot be easily acquired. They must be built over time at a very local level.

Many private equity firms also need to develop capabilities to create value in their holdings by providing management expertise and strategic guidance. They need people with the necessary business sense and field experience to make decisions that general partners will trust. In particular, there will be a growing need for mentors who can nurture relatively small companies, which is a skill in itself.

Pursuing new investment strategies in Africa will be challenging for many private equity funds, and building local capabilities may seem costly—particularly in a region where funds are already struggling to generate the returns that their investors expect. By investing to build organizations that can navigate Africa’s complex investment environment, gain an inside track on the best deals, and add value to companies, firms can build powerful competitive advantages. The bold actions taken now could well differentiate the winners from the losers in what promises to be the world’s greatest growth market for private equity.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the efforts of our BCG colleagues Paul Acheson, Stéphane Baleston, Nizar Bennani, Abdeljabbar Chraïti, Jérôme Hervé, Adam Saga Ikdal, Hans Kuipers, Stefano Niavas, and Antoon Schneider.