The vote in favor of “Brexit,” Britain’s exit from the EU, has created significant uncertainty for the UK, the EU, and global economies. The arrangements for the UK’s departure and the terms and timing of the eventual exit are unclear. Resolving the situation will likely take several years. There might be little immediate change—but it is safe to assume that political and economic uncertainty will reign for some time.

Undoubtedly, the long-term economic impact for the UK is negative. According to most economists, the UK’s long-term (2020 and beyond) real GDP post-Brexit will be 3 to 8 percentage points lower than the GDP that the nation would achieve if it remained an EU member.

The near-term effects are bleak as well: the UK economy is likely to see a sustained period of low base rates, higher inflation, lower consumer confidence, deflated real estate prices, higher unemployment, and a weaker pound (already, the pound has sunk to a 30-year low against the US dollar). Both Standard & Poor’s and Fitch have cut their ratings for the UK, and the International Monetary Fund has knocked almost 1 percentage point off its forecast for UK growth in 2017—the largest cut for any advanced economy.

The negative outlook will likely have a detrimental impact on banks’ performance across all business lines. Retail- and corporate-banking businesses are likely to see downward pressure on interest margins, less appetite for credit, and an upswing in loan losses. Investment-banking revenue may decline in the short term, if greater uncertainty drives a slowdown in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and capital-raising activity. Investment managers will see a reduction in assets under management (AUM), accompanied by a shift toward lower-risk asset classes.

In addition, the uncertainty is likely to increase funding costs for UK banks. Credit default swap spreads widened considerably—well above the levels that were seen at the time of the Scottish referendum—following the Brexit referendum result, implying a higher cost of longer-term bond issuance (although the spreads have subsequently narrowed somewhat). Both the reduction in the value of sterling-denominated collateral and the credit-rating downgrade will force a requirement for additional collateral.

In this article, we explore potential scenarios for Brexit itself and for the impact of Brexit on financial institutions. We also recommend actions that banks should take—now.

What Could Brexit Look Like?

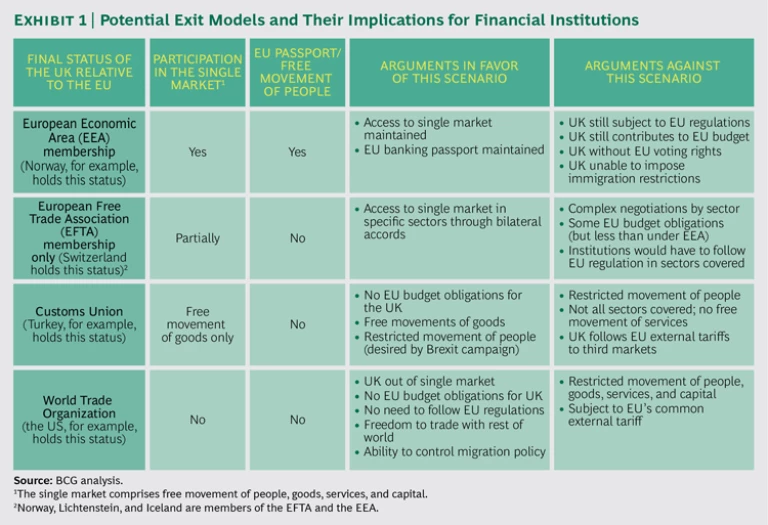

Each of the several potential exit models for the UK would result in a different set of agreements between the UK and the EU. (See Exhibit 1.) Assuming that the UK triggers Article 50 of the European Union treaty and Brexit ultimately happens (some parties suggest that the UK will find a way to sidestep the exit, perhaps even through a follow-up referendum), four broad subsequent scenarios are possible, though the specific terms under any scenario will be subject to lengthy negotiations:

- The UK could remain within the European Economic Area (EEA).

- It could become a member of the European Free Trade Association.

- It could join a customs union (which would allow the free movement of goods only).

- It could exit the single market entirely and negotiate with the EU as a member of the World Trade Organization.

The ultimate scenario and terms of exit may limit financial institutions’ continued ability to serve EU customers and clients from a base in the UK. Moreover, the precise terms of the UK’s exit from the EU will take years to define but could challenge the UK’s ability to “passport” services into Europe (and vice versa), which would affect all financial institutions (in particular, investment-banking, asset management, wealth management, payments, and cash management activities).

If passporting into the EU from the UK is not allowed following Brexit, a UK or non-EU financial institution operating in the UK may need to establish a fully authorized branch or subsidiary in the EU—if it does not already have one—in order to access European markets. Depending on the outcome of negotiations between the UK and the EU, these subsidiaries may need to be “substantial” (beyond merely a light footprint) and both independently and robustly capitalized to be compliant. This scenario could equally apply to a European bank with an operation in the UK, which may need to “upgrade” its UK operation with additional capital.

Ultimately, we are likely to see some banks move activities from the UK to other locations, either preexisting or newly established, in the EU. This is particularly likely for investment-banking activities (for example, the trading and clearing of euro-denominated derivatives) and asset management (where EU gateway hubs will be required for the distribution of certain funds). It may mean that some banks will split sales and coverage from trading and clearing activities. The need for such a “split subsidiary” model will undoubtedly create diseconomies of scale, higher complexity, and inefficiency.

Data will also be a critical consideration. Depending on the terms of exit, it might be necessary to put in place a specific data-sharing agreement, akin to the EU-US Privacy Shield that was launched on July 12, 2016. If an agreement cannot be made regarding the UK, the EU may block data flows, which would create significant challenges for financial institutions (and other industries).

What Does Brexit Mean for Different Types of Banks?

The considerations and the degree of risk posed by Brexit vary significantly across different types of financial institutions, depending on their business lines, customer and client mix, and current operating model. In general, the primary concern for UK banks that serve predominantly UK customers will be domestic macroeconomic conditions; no substantial changes to organization or operating model are likely to be required. Conversely, banks with investment-banking or asset management activities, particularly if they are using the UK as a platform to serve clients in the EU, could well be affected by both economic conditions and the requirement to change their operating model.

Given that the potential impact of Brexit will vary materially across institutions, considering some examples is helpful.

A UK Retail Bank That Serves Predominantly UK Customers. In this case, the primary concern will be the negative outlook for the UK economy, which is likely to have a detrimental impact on retail-banking performance. Base rates are likely to remain lower for a longer period of time, which will keep net interest margins under pressure. Higher inflation and a reduction in consumer confidence will lead to deleveraging, reducing loan growth. Overall, banks will see downward pressure on retail-banking revenue growth.

These banks are also likely to see an increase in loan losses as GDP falls, inflation increases, house prices decline, and unemployment grows. It is important to note, however, that lending quality is generally higher than it was in the buildup to the financial crisis, so any increase in loan losses may be less pronounced.

Potential passporting issues are likely to be less of a concern for these banks, given that most customers and clients are in the UK. As for many organizations, however, there may be implications for a bank’s UK workforce, depending on the proportion of people from the EU requiring permits to work in the UK and, of course, on the eventual terms of exit for the UK.

An additional complication: the potential for a Scottish referendum in the wake of Brexit. Banks with high exposures in Scotland could face further uncertainty and downside risk if this occurs.

A UK Bank That Includes Retail-, Corporate-, or Investment-Banking Operations or Asset Management Operations and Serves Predominantly UK Customers and Clients. This is similar to the first case but includes a more complex set of activities. As in the first example, the principal concern for these banks will be the outlook for the UK economy. In addition to the potential impact on retail-banking performance, these banks will face challenges in their corporate- and investment-banking and asset management operations.

The negative outlook for GDP growth in the UK economy implies that corporate-banking revenue pools will likely shrink or stay flat over the next five years. The specific impact will vary by institution, depending on the client sector mix and the product mix. But overall lending and payment volumes will undoubtedly decline as corporate clients suffer weaker financial performance (resulting from a weaker UK economy and potentially from a weaker pound). As in retail banking, loan losses will also likely increase, probably with a one- to two-year time lag.

Trade volumes will likely decrease, although documented trade as a proportion of total trade could rise as risk increases, which would dampen the effect. But trade finance contributes a relatively small proportion of total corporate-banking revenue and will be less of a concern than the impact on lending and transaction banking.

Overall, combined with additional capital burdens, the implication is a weaker outlook for corporate banking’s return on equity. To weather the storm, banks will need to tightly manage loan losses (particularly in the client sectors that are most vulnerable to a weak UK economy or that are reliant on trade with the EU), seek to increase revenue by repricing, and keep tight control of operating costs by accelerating or deepening existing cost reduction programs.

In investment banking, we are likely to see a negative impact on revenue in the short term, with return on equity continuing to fall (remaining below the cost of equity). Performance will be mixed by product, however.

The primary-market business could face a short-term decline, driven by uncertainty, high market volatility, and lower market confidence. M&A, along with equity capital market businesses, may come under pressure (although in recent weeks M&A activity has appeared to be holding up given depreciated prices). In the medium term, M&A and corporate finance activity may pick up as clients restructure. Cash equities will also likely suffer from reduced margins owing in part to write-downs, despite the benefits of volatility and increased exchange volumes.

Equity derivatives, however, will benefit from increased volatility and hedging, and prime services will see an increase in cash balances as hedge funds take short positions in volatile markets. Foreign-exchange and rate-trading revenue will increase as volatility in both exchange rates and European government debt drives trading performance.

In asset management, the consequences of the Brexit vote will likely lead to a reduction in AUM. We will probably also see investors shift to lower-risk (lower-margin) investments. Together, these trends would create revenue pressure for asset management divisions. Liquidity risk would increase with higher redemption rates, coupled with specific risks to any illiquid asset classes (such as property). Several major players have already been forced to freeze redemptions of assets after rapid outflows.

Passporting is likely to be less of an issue for this type of institution, which serves predominantly UK customers and clients. Nonetheless, depending on the exact terms of the UK’s exit, certain investment-banking operations may need to be managed separately within the EU. For example, euro-denominated derivatives may need to be traded and cleared from a base in Europe, even if traded between two non-European counterparties.

As with the first example, there may be implications for the UK workforce, depending on the proportion of people from the EU requiring permits to work in the UK.

A Non-European Bank That Has Corporate-Banking, Investment-Banking, or Asset-Management Operations and Serves the EU (with No Other Operations in the EU). This differs from the previous example in that it focuses on non-European banks rather than UK-based banks. In this case, the central concern in the short term is likely to be exposure to the UK and EU economies. And, as described in the previous example, the slowdown would affect corporate- and investment-banking performance as well as asset management performance.

Beyond the macroeconomic impact, the potential issues associated with passporting are likely to be more of a concern for a non-European institution using the UK as a gateway to serve clients in the EU. Depending on the eventual terms of exit, such an institution may need to establish a fully authorized branch or subsidiary in the EU in order to access the European market. More likely is a split-subsidiary model in which the firm balances separate hubs in the UK and in Europe, each separately capitalized. Such a setup would substantially increase administrative costs and would reduce efficiency in capital and liquidity management.

We assume that, in the post-Brexit environment, an operationally independent EU subsidiary will be a prerequisite for serving European clients, and we estimate that annual operating costs for capital market businesses will increase by 8% to 22%, depending on the extent of existing European operations as a starting point. At the low end of the range would be an already-diversified bank, whose costs would primarily be driven by the additional headcount and infrastructure required to implement increased capacity in Europe. At the higher end of the range would be a bank concentrated in the UK, which would incur additional (duplicative) costs for infrastructure, IT, and corporate functions. This

Banks of this type would need to consider which operations should be undertaken in Europe and which in the UK. For example, in capital market activities, euro-denominated mandated derivatives would likely have to be cleared in Europe; if so, banks’ clearing operations and collateral pools may need to move to the Eurozone. The European Central Bank might not allow non-EU-based institutions to handle custody for EU clients, which would necessitate either relocation of these activities inside the EU or entering into a custody agreement with an EU-based entity. Some financial institutions may choose to split trading desks, with euro-denominated asset classes in the EU and the rest in the UK.

Passporting rights will also be an issue for asset management activities. The Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive could probably be extended to the UK as a third-party country operating under “equivalent” regulation, with a number of limitations and subject to approval from the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). To distribute UCITS funds in the EEA, however, the UCITS directive requires the domiciliation of funds and their management companies in the EEA, meaning that UK asset managers would need to establish a gateway hub in the EEA if they do not already have one. Likewise, investment management businesses in the UK would also require an EU gateway hub to provide products and services in the EU.

Those banks setting up separate subsidiary operations in Europe would also need to decide which location in the EU is most attractive, of course, and tackle the practical issues associated with any move—such as putting in place the required infrastructure, legal arrangements, and staff (who would need to be relocated or newly hired). These banks would also need to revisit recovery and resolution plans and reassess their ring-fencing requirements.

Some banks may choose to take advantage of this situation to radically reduce costs and reconfigure their operating models. Such an initiative would likely include a streamlined headcount, reduced compensation, leaner operations, automated processes, use of industry utilities to reduce the running cost of low-value-add activities, and transformed sales coverage models.

Of course, there remains a great deal of uncertainty regarding which requirements will be placed on these banks following Brexit. For example, the next iteration of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID 2), due in early 2018, has a clause that may allow non-EU firms to provide services to institutional (but not retail) clients within the EU, without the need for a local presence in the EU. However, this would require the UK’s regulatory regime to be granted “equivalence” status by the ESMA. It is not clear at this stage how regulators will interpret the MiFID 2 clause or, indeed, whether equivalence status will be granted—uncertainties that will surely form part of the broader UK exit negotiations with the EU.

Some banks may go ahead and set up European subsidiaries to lessen the uncertainty and avoid disruption later. Some may also consider M&A opportunities in Europe as a way to buy rather than build a European presence.

A European or International Bank That Has a Substantial Corporate- and Investment-Banking Operation in the UK as Well as Elsewhere in the EU. The main short-term concern in this example is likely to be the macroeconomic consequences of Brexit. And much like the institutions in the previously described examples, these banks will likely suffer from exposure to the UK economy. The EU is likely to experience a spillover, with lower GDP growth and reduced appetite for credit, leading to lower loan growth, higher loan losses, and higher funding costs for banks. For large international banks, the proportion of their assets exposed to the UK and EU may be relatively low, and perhaps Brexit will be less of a concern. But for predominantly European banks, the economic impact could be much more significant.

The potential passporting issues described previously may be less critical for banks with existing operations in Europe, because they are unlikely to need to establish entirely new European subsidiaries. But there may also be a need (or an opportunity) for these banks to move some operations currently based in the UK to their other EU location(s). Again, this may include the trading and clearing of euro-denominated derivatives, as well as custody services. These banks should assess which activities may be affected under different potential exit scenarios to determine which operations should move.

A further consideration for European banks is the potential additional requirement for capital for their UK operations. While the UK is a member of the EU, UK branches of European banks do not need their own capital. This may change, however, if the UK leaves the single market. Our research suggests that European banks that must “upgrade” their UK operations could be looking at an aggregate capital bill as high as €30 billion to €40 billion.

European and international banks will also face a longer-term question: Will their UK business continue to be attractive? Some may conclude that the negative economic outlook for the UK means that they should exit some business lines, or even exit the UK altogether. Indeed, if there is a need to move substantial operations out of the UK to Europe, the justification for a UK operation may diminish. Conversely, some banks may see Brexit as an opportunity to gain share in some business lines or to identify niche value creation opportunities.

What Actions Should Banks Take Now?

Given the market reaction following the Brexit announcement, we expect that all banks will now move to assess the near-term implications, apply any necessary corrective measures, and reassure investors. These efforts will include managing counterparty risk and credit exposure, determining risks to long-term funding, and assessing exposure to devaluation and volatility in the pound.

Other actions are required as well. Given the high level of uncertainty that is likely to prevail for some time, banks need to immediately assess their strategic options and operating models, develop contingency plans, and, where appropriate, begin moves to mitigate uncertainty and risk. They should also consider how to best take advantage of the situation, including how to capitalize on any opportunities that may arise.

In our view, financial institutions should take the following steps:

- Conduct scenario planning. Develop a variety of economic and political scenarios, for both the near term and the long term, and assess the implications of each scenario (for example, the impact on business performance, areas of weakness or risk and how to mitigate them, upside opportunities, and capability requirements). Define potential “trigger points” that may narrow potential scenarios and lead to action with greater confidence, and identify any “no regrets” moves that can or should be made now to reduce uncertainty or satisfy client demand.

- Review the UK strategy. Conduct a strategic review across business lines (or products) under these different near-term and long-term scenarios, identify value creation opportunities, and develop options to mitigate downside risk. Refine the strategy by business line and product type, come up with options to optimize performance (including identifying opportunities for cost reduction), and, if applicable, reassess the role of the UK business within the context of the overall group. Ask, for example: What are the implications for group-level investment in the UK versus elsewhere?

- Assess the potential implications for the organization and operating model. Clearly define the current operating model and determine activities that may be affected by Brexit (under different exit models and terms of exit), in particular those relating to any limitations in the UK’s passporting rights. For these affected activities, develop different organization- and operating-model options (under different scenarios) and assess the attractiveness of each, including infrastructure and headcount requirements, cost to implement, and funding.

- Examine the implications for the UK workforce. Identify EU citizens who are working in financial institutions in the UK, and assess any risks related to their eligibility to continue to do so in a post-Brexit environment. Anticipate signals and trigger points that may arise during negotiations. Take action to plan for and mitigate the potential risks.

- Engage customers and clients. Communicate extensively with customers as well as clients to listen to their concerns. Reassure them that the bank is responding effectively to the situation and that it will continue to serve their needs.

- Engage regulators and government officials. Stay attuned to political developments, and engage with regulators and officials to seek as much clarity as possible as soon as possible. To the extent that it’s feasible, try to influence the “answer.”

- Consider the potential implications of planned regulations and structural reform. Determine whether Brexit has any consequences for regulation that is currently being planned as well as for expected future structural reform.

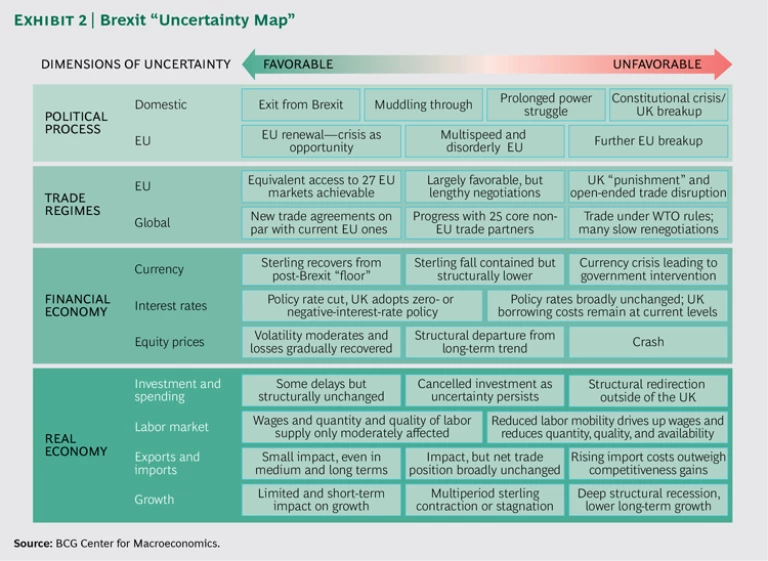

Given the impossibility of forecasting the precise impact of Brexit with a high level of confidence, we recommend a scenario-based approach to planning, modeling, and preparing for multiple potential outcomes. Such scenarios should incorporate various dimensions of uncertainty, including the political process (quick and orderly versus long and complex), the macroeconomic outlook, and the success (or otherwise) of the UK’s efforts to negotiate new trade agreements in a favorable and timely manner.

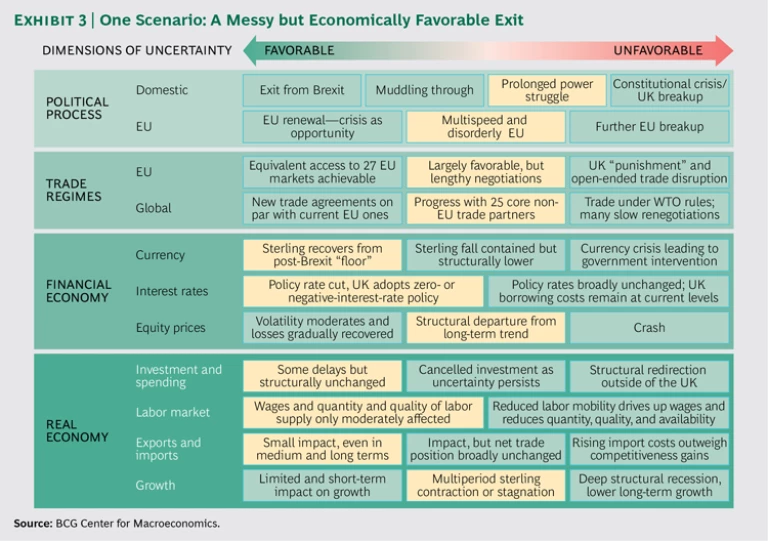

Exhibit 2 outlines a potential “uncertainty map” that can help financial institutions think about the different dimensions of uncertainty and the specific outcomes that may play out. We suggest creating a set of plausible scenarios based on a combination of these factors. For example, Exhibit 3 shows a scenario that is “messy but economically favorable.”

For each scenario, we suggest that all financial institutions:

- Stress-test the resilience of business plans against the scenarios.

- Determine areas of weakness and take prudent measures to ensure against downside risks.

- Identify “no regrets” moves that span scenarios.

- Create options to capitalize on upside opportunities.

- Select where to take a stance and where to hedge.

- Build contingencies and trigger points into plans.

- Develop a view of required capability building and corporate initiatives.

Some institutions may feel sufficiently confident that certain scenarios will play out, so they might be prepared to place bets now. Others may want to take action to limit the uncertainty—thus becoming “scenario agnostic”—or to create a list of options and ready themselves to move quickly when the outlook becomes more clear.