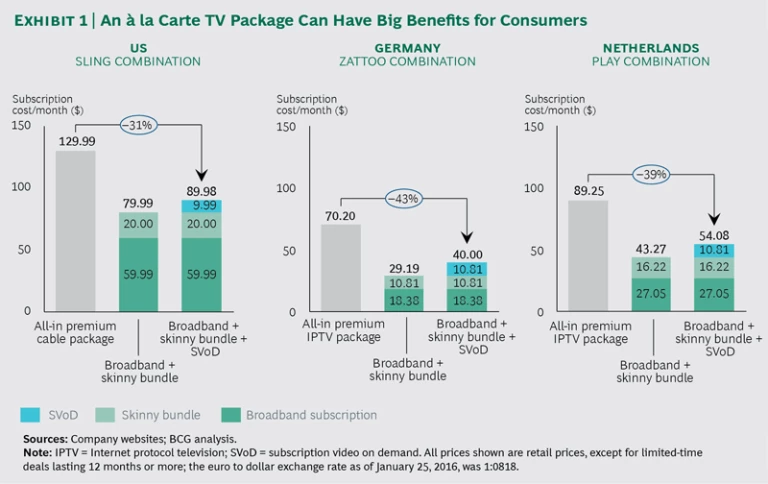

The television industry that we’ve long known is gone—or at least, it’s looking mighty different. Forget the days of gathering around the living room TV for a favorite Saturday night show. Today’s viewers are pulling out tablets, laptops, and smartphones, accessing video content when—and increasingly where—they choose. This transformation hasn’t been subtle. And for industry players, neither are the consequences. In growing numbers, consumers are replacing their traditional cable and satellite TV packages with smaller, more customized, and often less expensive mixes of programming, cobbled together from an array of online and on-demand services. (See Exhibit 1.)

The convenience of such “over the top,” or OTT, TV and video has sparked a major shift in how content is produced, delivered, and consumed. (See The Digital Revolution Is Disrupting the TV Industry , BCG Focus, March 2016.) But for telcos—many of which have only recently seen their interest and presence in this sector grow—it has spurred something else: an opportunity. Broadband infrastructure, the bread and butter of fixed and mobile telcos, has become a key asset in the new TV and video landscape. Already we are seeing some cable companies get that message. Those that are packaging broadband with smaller, or “skinny,” OTT content bundles seem to be weathering the online storm better than their more traditionalist competitors.

If telcos can combine connectivity with compelling content, they can play a central role in the emerging online video value chain. And as they capture new customers, they can boost the penetration rates of their mainline broadband products. That’s a tempting proposition, and a potentially lucrative one. But turning opportunity into growth will require telcos to make careful choices—and to make them soon.

The OTT Disruption

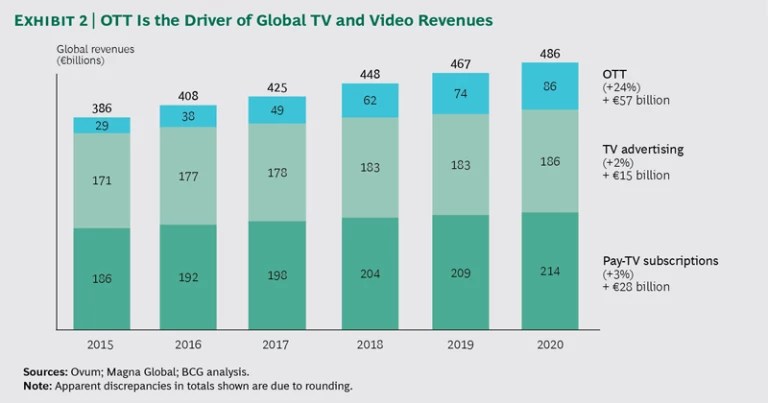

For the television business, OTT isn’t just the next big thing. It’s poised to be the biggest thing—the industry’s key driver of growth and disruption—over the next several years. Between 2015 and 2020, global revenues deriving from OTT video are projected to increase from €29 billion to €86 billion, a growth rate that will outstrip that of both TV advertising and pay-TV subscription revenues. (See Exhibit 2.)

It’s a big pie, and not surprisingly, many players are looking to take a bite of it. There are the online streaming services, like Netflix and Hulu, offering vast libraries of on-demand content. There are Internet-based “live” TV services, like Zattoo and Sling TV, providing more traditional, linear TV via any broadband connection. And there are the more old-school players: the television broadcasters, pay-TV channels, cable companies, and satellite providers.

The OTT landscape has created some significant challenges for satellite and cable providers in particular. Fears of cord thinning or outright cord cutting—subscribers opting for smaller bundles or jettisoning service entirely—haven’t been unfounded. In 2015, the US pay-TV market saw its biggest customer exodus ever: a net loss of some 560,000 customers. In Europe, where OTT has been less popular but is rapidly gaining ground in many markets, growth in pay-TV subscriptions is expected to slow as well.

Indeed, OTT’s trajectory is now particularly steep outside the US. In Europe, subscriptions to online video-on-demand services increased by 50.3% between 2014 and 2015. Central and Southern Asia saw an even more remarkable 159.4% jump over the same period. (By comparison, North America—starting from a much higher base—saw a 20.7% increase.)

Yet for distributors with a broadband offering, the outlook need not be doom and gloom. While it has meant significant investment and effort, some established players are already staking out a position in OTT, offering skinny bundles together with broadband. And for one US distributor, the bet seems to be paying off. After experiencing several quarters of net subscriber losses, it was able to add tens of thousands of new customers in the fourth quarter of 2015. While much of this growth can be attributed to traditional products, online offerings clearly played a role: some 15% of this provider’s total video subscriptions are now centered on skinny bundles.

An Opening for Telcos

Telcos that are quick to create a winning OTT strategy can gain a significant competitive advantage, particularly outside the US, where many markets are experiencing rapid growth in online viewership but where content owners, networks, and distributors have been slower to embrace this emerging pathway.

To create such a strategy, telcos will need to take a more segmented view of customer needs. While some customers will still want the big bundle, others won’t. In addition, telcos must take an integrated approach that allows them to develop their OTT strategy from multiple angles. That means thinking carefully—and asking key questions—about five essential elements: the offer, the monetization model, the content, the product and technology strategy, and the organization.

Telcos have choices about each of these elements and making them won’t always be easy. To help guide the way, we look at the main routes companies are taking in their OTT journeys—and why some may work better than others.

The Offer

What should a telco’s TV and video offering look like? While the details will vary, there are two main paths. First is the premium option. This type of offering would integrate traditional TV and OTT content, with added navigation and discovery features. In essence, telcos would strive to become customers’ universal remote, providing fast, intuitive access to both linear and on-demand content. Alternatively, telcos could opt for a smaller, standalone OTT product—a skinny bundle that would typically include a basic selection of linear channels and perhaps some premium channels and on-demand content.

Which road to take? That depends on a telco’s current position, its ambitions, and the resources at its disposal. The premium route could make sense for a telco with serious pay-TV aspirations: one that already is—or hopes to be—a significant player in TV and video subscriptions. Such a telco would have a large customer base that it wishes to migrate to upper-tier products and higher average revenue per user (ARPU). The typical incumbent telco, having already launched IPTV service, would fit this bill.

Operators taking this route will need to make considerable investments and, if they don’t already have it, acquire sufficient technical expertise. They must also develop or acquire a wealth of OTT content or partner with the right third-party services. Integrating all the parts into a seamless user experience can be tricky, but telcos that successfully deploy a premium offering—and occupy that central position in navigation and discovery—can become go-to sources for all TV and video content.

The skinny bundle is a decidedly less ambitious route. But for telcos that don’t have the deep pockets or bench strength that a premium offering requires, it can be the sounder approach. Skinny bundles make sense, too, when the focus is less on becoming a major TV and video provider and more on growing a fixed or mobile broadband business. And it’s a strategy that need not break the bank. White-label solutions let telcos launch OTT offerings without making big investments in platforms and capabilities.

Keep in mind, however, that the best answer doesn’t always boil down to A or B. Different customers have different preferences. The fat bundle isn’t always anathema; the skinny bundle isn’t always heaven sent. The key is to focus on emerging and changing TV and video consumption patterns and to realize that the optimal product portfolio may need to be varied as well.

Already there are some good examples of providers taking a more varied approach. In the UK, Sky offers Now TV, a lower-priced, OTT-only service that works via a small streaming device connected to a TV, or on mobile devices through a partnership with Vodafone. In the Netherlands, KPN offers an app-based skinny bundle called Play, which brings 22 linear channels and on-demand content to phones and tablets (and to TVs via Google’s Chromecast streaming device) without requiring customers to get their fixed or mobile broadband from KPN. Crucially, these players also offer more traditional-looking fat bundles. They are, in effect, de-averaging their offerings and providing choices—a necessary step if they are to capture the largest possible share of the market.

The Monetization Model

There are three general ways that content can be monetized: through subscription fees, advertising revenue, and one-off transactions (typically, renting or purchasing specific content). Mobile operators also have a fourth route: monetizing mobile data—the increasing amount of megabytes that customers are using to download and stream video.

Until now, cable and satellite providers, as well as telcos that offer TV products, have typically followed the subscription model in most global markets. Yet video monetization need not end with subscription revenues. Recently, we have seen large deals in which telcos have acquired capabilities in advertising technology. This is both an intriguing move and a savvy one, because gaining a foothold in the center of the advertising ecosystem can prove highly beneficial. Integrated telcos could use customer and location data from across their fixed and mobile platforms to deliver targeted—and to recipients, highly relevant—advertising. In the short term, this strategy might be the province of the biggest players, which will have the scale to set up meaningful alternatives to the global ad-tech giants.

While online and mobile advertising are the natural focal points for individual addressability, targeted advertising will also take root in traditional linear TV not far down the road. Ads will be tailored to the viewer and dynamically inserted into the linear stream.

Telcos that own the last mile to the customer will be able to participate in these video advertising models. And this will be no small pie: by 2020, annual revenues from online and linear advertising are expected to exceed €240 billion.

For many telcos, data monetization will also be an issue. Should telcos embrace the idea of “free data” for their own (or their partners’) OTT products, or should usage be counted against the subscriber’s data allowance? One observation is that free doesn’t necessarily have to mean no additional revenue. Already, some mobile players are using smart content bundling and authentication of services to drive not only customer growth but also sales of larger data packages. The most prominent example is T-Mobile’s Binge On offering, which gives customers free mobile video streaming if they use select video services (including Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube) and purchase a higher-tier data package. Another example is Vodafone UK’s partnerships with Sky, Spotify, and Netflix, which have caused data consumption and presumably ARPU (in the form of larger data packages) to increase.

The Content

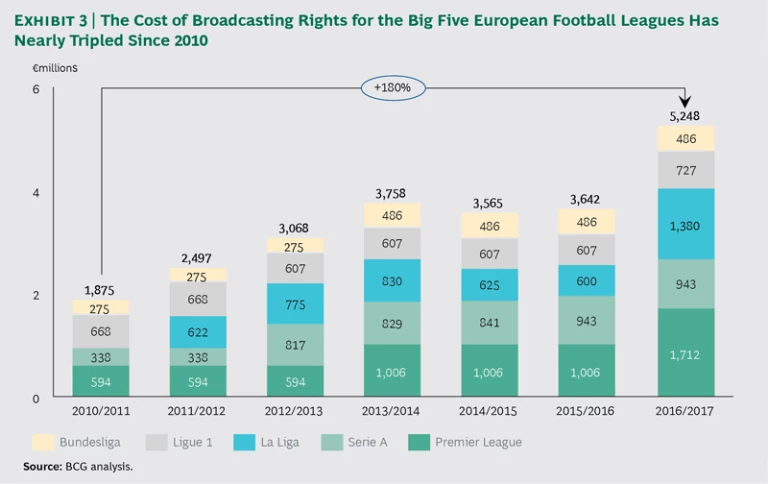

Content can be a crucial differentiator for a video distributor. A compelling “only available here” TV series or sporting event can bring viewers—and a powerful competitive edge—to a platform. But exclusivity doesn’t come cheap. In Europe, for example, the cost of top-tier sports content has exploded in recent years; the price of broadcast rights from the five largest football leagues, for instance, nearly tripled between the 2010/2011 and 2016/2017 seasons. (See Exhibit 3.)

For telcos with deep pockets and a solid understanding of what customers want, investments in exclusive content can pay off. Even if licensing fees outstrip the direct revenues that the content produces—not a rare phenomenon—companies can realize important benefits in customer acquisition and retention. And they can do so on both the fixed broadband and the mobile sides. In general, though, only major players that have significant pay-TV ambitions linked to their broadband business—players that see video as the primary way to drive customers to their platform—are likely to apply this strategy (or apply it sensibly, at least). Once again, integrated incumbents will be the most likely candidates.

For other telcos, the default “minimal spec” for content should be a skinny bundle of essential linear channels with add-ons for premium channels (the model pursued by OTT players like Sling TV). But it’s not enough simply to send content the viewer’s way. Time-shifting functionality and intuitive search and discovery are becoming table stakes for serving a new generation of consumers whose consumption is shifting from big TV screens to mobile devices.

Linear channels may seem like old news in an increasingly on-demand TV and video landscape, but they still are essential for great swaths of viewers. They provide the live news, sports, and other “in the moment” programming that these customers want. Indeed, this is a key reason why we haven’t seen even more cord cutting and thinning. So like exclusive content, linear channels—along with an intuitive, modern way to navigate and watch them—can spark differentiation. That makes them a potentially crucial part of a TV and video strategy.

The Product and Technology Strategy

Telcos also have options on how to implement their video solution. Is a bespoke technical platform preferable to an off-the-shelf product (a category in which the number and capabilities of providers are growing)?

The answer isn’t always straightforward. A telco’s size, of course, is an important factor, but so too is its level of ambition. Are TV and video to be central to the business or more a way to drive customers to a broadband product? Telcos also need to weigh tradeoffs in cost, complexity, and time to market.

Large operators that aspire to be key TV and video players—and can shoulder the cost and development burdens of bringing out a best-in-class in-home and mobile offering—should consider a full-blown integrated platform. The idea, once more, is to position oneself as a de facto universal remote: a gateway to all video content. Connected to a TV through a device resembling a traditional set-top box, this offering would also work with tablets and smartphones via TV Everywhere apps (which authenticate subscribers and enable them to access content when they are not in front of their TVs).

But if ambition, speed, and cost point to a less complex solution, telcos will find that they can choose from an array of end-to-end turnkey platforms. In Europe, smaller telcos have been opting for third-party IP-based solutions—such as Zattoo—to distribute their video content to home and mobile screens. This approach can give a telco a robust video platform at less cost—and in less time—than a proprietary solution would likely require. Indeed, there is often little downside to the strategy. The best off-the-shelf platforms not only handle the real-time streaming component of OTT video but also support multiple devices, manage digital rights and geographic restrictions for content, provide a wealth of analytics, and even facilitate e-commerce.

Not surprisingly, some larger players have been looking to turnkey platforms as well. HBO, for example, uses the MLBAM platform (developed for Major League Baseball but now used by a roster of other organizations, including the National Hockey League and Sony) for its OTT video offering, HBO Now.

The Organization

Structurally, an OTT TV and video business can be run as an integrated part of the current organization or as a standalone company. But for telcos that envision a TV and video solution that is tightly linked to their broadband and mobile offerings, integration is key. They will need to keep product development, marketing, and sales for these products in sync—which means running the business from within the existing organization.

In some cases, however, a separate entity may be the better move. For example, a telco may have lesser ambitions for TV and video; it may not be looking to integrate them fully into its product structure. The standalone option can also work well for players with a multimarket footprint. A separate TV and video unit, with talent, skills, and tools culled from the telco’s full global presence, can facilitate knowledge- and resource-sharing far more easily than a loose coalition of country-specific organizations.

Consumers are already discovering, and seizing, the advantages of OTT content. They are streamlining their TV bundles—and their TV budgets. In the process, they’re gaining more value: paying for the content they want and for fewer, if any, of the channels they never watch. For telcos, OTT TV and video can bring significant rewards as well, helping them compete in a promising, fast-changing space and grow their broadband business while they’re at it. That’s a path telcos don’t want to miss—and one that they need to start heading down now.