In a world of economic uncertainty, Nordic countries have stood apart. The countries’ gross domestic products have continued to grow strongly. Nordic equity markets have done well. And the countries have a good track record of building sustainable growth companies.

That these accomplishments have not come at the expense of equality, trust, and collaboration—bedrock values in the Nordics—has increased the world’s admiration for the countries. Tiny Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden have been able to increase their standards of living, maintain their social benefit systems, and retain political stability for the better part of 50 years.

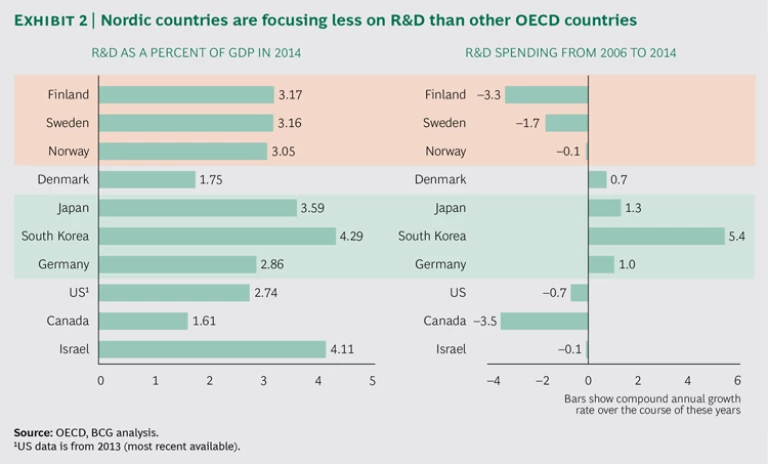

But the economic model that underlies the Nordics’ success is in jeopardy, as external and internal challenges eat away at the countries’ advantages. Externally, competitors like South Korea and Slovakia have moved much faster to transform their business environments, exposing areas in which the Nordics have been too deliberate. Internally, the Nordics’ once-big lead in innovation and R&D has been undermined by the countries’ slow embrace of digitization. There is surely more than one reason for the uptick in mortality rates among Nordic companies in recent years, but most companies’ less than full-throated support of a digital agenda certainly hasn’t helped. Likewise, there may be no single reason that so few of the Nordics’ top companies (varying from one in every six companies in Sweden to none in Finland) have come into being in the last 20 years. But one clear obstacle is the Nordic ambivalence about entrepreneurship—an ambivalence partly rooted in the countries’ own policies.

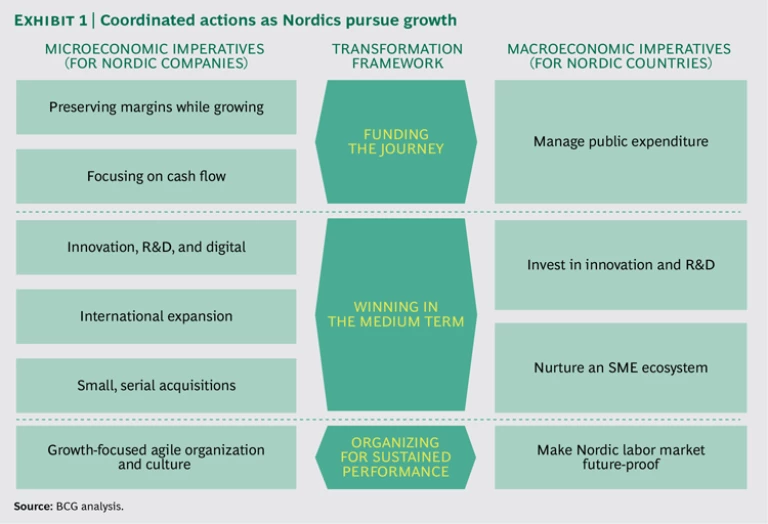

BCG has done a wide-ranging analysis of Nordic countries’ growth challenges to understand how Nordic companies must adapt to intensifying competition, and the role of Nordic governments in revitalizing their private sectors. One thing is clear: incremental change won’t do. With the changes taking place globally, Nordic countries and Nordic companies must aim for a larger transformation and pursue it together (see Exhibit 1).

Funding the Journey

The sort of change needed in the Nordics requires investment. Companies and countries must both retrain existing workers, embrace digital technology, foster more of an entrepreneurial spirit (in some cases by attracting high-skill immigrants), and buy what they can’t build. This all takes money.

Nordic companies must find ways to preserve margins even while they’re growing. They must also generate cash flow in order to have the resources they’ll need to invest in growth initiatives. The 73 sustained growth Nordic companies we studied (the list was derived from an analysis of 1,301 public companies headquartered in the Nordics) have clearly performed well in this regard. Their average free-cash-flow yield rose by a factor of 2.5 over the last five years, versus a cash-flow decline for other Nordic companies.

For their part, Nordic countries—which with the exception of Norway have run deficits since the financial crisis of 2008—must do a better job of managing their public expenditures and of improving productivity. If they don’t, they won’t have the flexibility to contribute to private initiatives and to support research in promising new industries.

Winning in the Medium Term

The Nordics’ shrinking lead in innovation and R&D shows up in metrics like R&D intensity (that is, R&D spending as a percent of GDP) and in the number of patents applied for in the Nordics versus elsewhere (see Exhibit 2). If Nordic companies excelled at commercializing their ideas, the weakening R&D numbers might not be so worrisome. Unfortunately, R&D commercialization isn’t a strength. More coordinated efforts are needed, including public-private innovation partnerships.

A particularly big concern relates to digital. Nordic companies are at a disadvantage because of regulations that restrict new business models and that inadvertently discourage startup activity. The countries need to develop technology agendas that are forward-looking and must do more to promote entrepreneurship. This includes increasing the availability of venture capital, which has become one of the most effective lubricants of new-company formation globally in the last 45 years.

Nordic countries must also look for ways to get their small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to focus on growth. High taxes are common in these countries, and that partly explains why so many business owners get their companies to a certain size and then don’t try to get any bigger. (A lot of the personal benefit these owners would derive from having bigger, more profitable businesses would be eaten up in taxes.)

Tax policy—especially as it relates to encouraging startup activity—is certainly something that could be looked at when it comes to SME growth. More direct forms of support would also be a good idea.

For instance, by putting more resources into agencies specializing in international trade, Nordic countries could help their SMEs expand geographically. Increased exports would allow SMEs to grow into more dynamic midsized firms, potentially helping the Nordics create something akin to Germany’s vibrant Mittelstand tier of companies. And of course, some SMEs would go farther and become true multinationals, bringing correspondingly bigger benefits to their countries.

Organizing for Sustained Performance

Being able to generate great commercial ideas and fund their development are characteristics of the best growth companies. But there would be nothing repeatable about a growth model—and the model could not generate sustainable gains—if it depended entirely on inspiration. Sustained growth must also be an organizational capability: part of a company’s DNA.

The organizational imperative starts with executives whose focus on growth is obvious in everything they say and do. It includes putting important strategy and growth discussions ahead of bureaucratic processes, and not vice versa as can happen at companies that try to squeeze in their major strategic decisions alongside other aspects of the annual plan.

Finally, companies should be agile in their approach to growth, including in their willingness to experiment with unconventional organization and operating models. Spotify is a good example. This Swedish company uses autonomous squads—teams of up to eight people—to do rapid product development and keep the company relevant in the fast-changing global market for online music streaming. Being willing to experiment with different structures and operating models is an approach that more Nordic companies should consider, especially if it allows them to create something of commercial value or get to market faster.

At the macroeconomic level, Nordic countries face their own talent and organizational challenges. Chief among these is the disruption that digitization is introducing into their economies. Between now and 2025, digitization will make as many as 600,000 jobs obsolete in the Nordics. A lot of workers will need to be retrained and redeployed. In addition, Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden will need to expand their domestic labor bases and adopt new immigration policies to make sure their talent pools are sufficient, in both size and skills, to carry them into the future.

The Urgency to Move Forward

Countries can’t just will their industrial sectors to be high-growth—the impetus must come at least partly from the private sector and from individual entrepreneurs. But it’s no accident that many of the world’s most dynamic companies have grown up in countries that are financially stable; that support science and industry on a national level; that have flexible regulatory environments; and that have highly motivated, educated workforces (including sizable immigrant populations). These countries provide a great foundation for company formation. Their best companies, in turn, become an integral part of their economies and burnish their international reputations.

In the short run, there are still enough big, successful Nordic companies to keep the countries’ economies healthy. In the long run, a replenishment of fading companies with dynamic new ones is essential to avoid a secular decline. There is every reason for Nordic companies and countries to think of each other as partners. They’re in this together.