This article is an excerpt from Creating Value Through Active Portfolio Management: The 2016 Value Creators Report (BCG report, October 2016).

2016 Value Creators Report

- Creating Value Through Active Portfolio Management

- The Role of Portfolio Management in Value Creation

- Bristol-Myers Squibb

- The 2016 Value Creators Rankings

Every company aspires to be a top value creator. Relatively few actually achieve this—and even fewer are able to sustain top performance over time. Doing so requires continually revisiting a company’s value creation strategy and adapting it to changing circumstances and new starting positions.

One of the most powerful ways to drive continual adaptation is active portfolio management . That is why we focus on that topic in this year’s Value Creators report. We begin by reviewing the world’s leading large-cap value creators for the five-year period from 2011 through 2015 in order to explore the dynamics that make sustaining superior value creation such a significant challenge.

The 2016 Large-Cap Value Creators

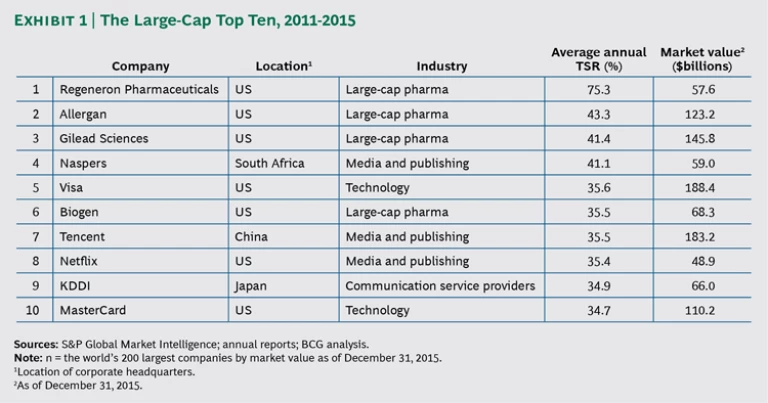

Exhibit 1 lists the top ten value creators among the world’s 200 largest companies. The ranking is based on average annual total shareholder return (TSR), which measures the combination of the change in share price and the dividend yield for a company’s stock over a specific period. TSR is the most comprehensive metric for value creation and the shareholder’s true bottom line. (See “The Components of TSR.”) Average annual TSR is the amount of TSR that a company delivers, on average, in each of the five years in our analysis.

THE COMPONENTS OF TSR

Total shareholder return (TSR) measures the combination of share price gains (or losses) and dividend yield for a company’s stock over a given period. It is the most comprehensive metric for assessing a company’s shareholder-value-creation performance, preferred by investment funds to measure business performance and, in some locations, a requirement for regulatory compliance.

TSR is the product of multiple factors. Regular readers of the Value Creators report will be familiar with BCG’s model for quantifying the relative contributions of TSR’s various sources. (See the exhibit below.) The model uses the combination of revenue (sales) growth and change in margins as an indicator of a company’s improvement in fundamental value. It then uses the change in the company’s valuation multiple to determine the impact of investor expectations on TSR. Together, these two factors determine the change in a company’s market capitalization and the capital gain or loss to investors. Finally, the model tracks the distribution of free cash flow to investors and debt holders in the form of dividends, share repurchases, and repayments of debt to determine the contribution of free-cash-flow payouts to a company’s TSR.

All these factors interact with one another—sometimes in unexpected ways. A company may grow its revenue through an EPS-accretive acquisition yet not create any TSR because the acquisition erodes gross margins. And some forms of cash contribution (for example, dividends) have a more positive impact on a company’s valuation multiple than others (for example, share buybacks). Because of these interactions, we recommend that companies take a holistic approach to value creation strategy.

To make it into the large-cap top ten, these companies had to deliver extraordinary TSR—an average of at least 34.7% per year. That’s enough to more than quadruple the value of each dollar invested at the beginning of the period and nearly three times the median TSR of 12.2% of the approximately 2,000 companies in this year’s Value Creators database. This year’s number one large-cap value creator, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, delivered a TSR of 75.3%, more than six times the median and more than 30 percentage points greater than the TSR of the number two company, Allergan.

For the second year in a row, biopharma companies lead the global large-cap ranking, taking four of the ten spots, including the top three. This dominance reflects in part the fact that the large-cap pharma sector was the second-best performer of the 28 industries in our analysis (the mid-cap pharma sector was the best). That industry-wide performance is even more striking when one considers that pharma was at the very bottom of the industry rankings in our study of the five-year period from 2006 through 2010.

Top Performance: Hard to Achieve, Even Harder to Sustain

Another interesting finding in this year’s large-cap top-ten ranking is that five of the companies—Regeneron, Netflix, Visa, KDDI, and MasterCard—are all newcomers to the list. Meanwhile, three—Allergan (the successor to Actavis, which acquired Allergan in 2015), Naspers, and Biogen—are appearing in the top ten for the second time; and one, Gilead, for the third. The only company on this year’s list that has appeared in our large-cap ranking for more than three years is the Chinese social media powerhouse Tencent, which has made the top ten for six years, five of which were consecutive (2010 through 2014).

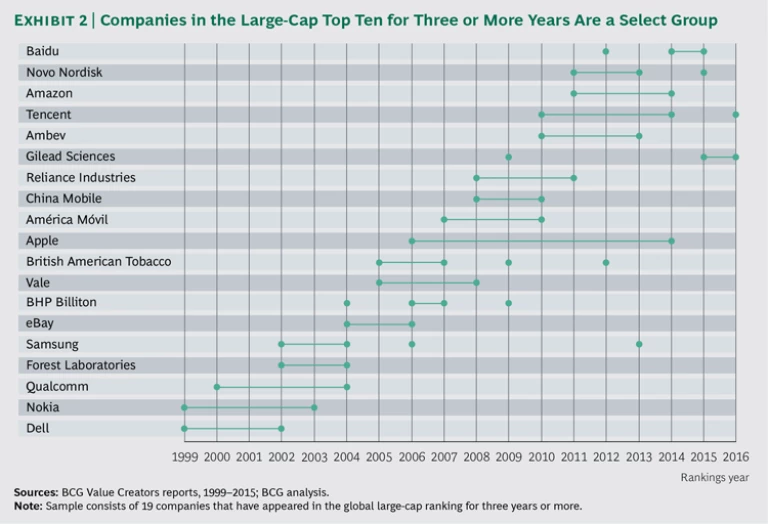

That kind of consistency is exceedingly rare. In the 18 years BCG has been publishing the Value Creators rankings, 89 companies have made it into the large-cap top ten. More than half, however—46 companies—have done so only in a single five-year period. In other words, those companies broke into this select group only to disappear from it in subsequent years.

Only 19 companies (roughly 21% of the 89 companies that have made it into the top ten) have appeared on the list for three years or more. (See Exhibit 2.) The only company to surpass Tencent’s sustained performance has been Apple, which first appeared in the large-cap top ten in 2006 and stayed on the list for the next eight years, through 2014; however, the company has not appeared in the top ten since then.

Why is it so rare for a company to stay on our top-ten list? To become a superior value creator—the kind that wins a place in our top-ten rankings—a company must massively exceed investors’ expectations. We are not talking about beating earnings estimates for a quarter or two. We are talking about delivering results that fundamentally transform the trajectory of the business.

This year’s number one large-cap value creator, Regeneron, is a classic example. Regeneron is a drug discovery business in the midst of what appears to be a vertiginous takeoff, thanks to its distinctive technique of placing segments of human DNA in mice and using the genetically engineered animals as a platform for the rapid (and, therefore, relatively cheap) development of medications that work in humans.

During the period from 2011 through 2015, Regeneron achieved a major breakthrough. Previously, the company had been regularly showing negative accounting earnings as it ploughed nearly half its operating income back into R&D. For example, it reported a loss of $222 million in 2011. But since the introduction that year of its first blockbuster drug, Eylea (a treatment for the most common causes of adult blindness), the company’s revenue has grown rapidly, and net profit in 2015 was $680 million. The strength of Regeneron’s drug discovery pipeline has led investors to push the company’s stock price to nearly 60 times expected 2016 earnings, an extraordinary valuation multiple.

It is in the nature of capital markets, however, to look forward and to continually capitalize expected future earnings in today’s stock price. As a result, top-performing companies tend to “fade” to average market performance over time. According to consensus estimates, Regeneron should roughly double its earnings by 2018. But if the company’s current stock price already reflects those expectations, then it would grow only at the rate of the risk-adjusted cost of capital for a company of its type (roughly 10%), causing the company’s P/E multiple to decline by about a third. Unless Regeneron can find ways to exceed, not just meet, investors’ expectations once again or to build new expectations for a subsequent wave of value creation, it will be extremely challenging to deliver the kind of TSR it has during the past five years.

It’s not impossible for a company to “beat the fade” to average performance, but it is a complex act that is difficult to sustain. Apple is the exception that proves the rule. A decade of product and business model innovation that brought the world the iPod, the iTunes online music service, the iPhone, and the iPad transformed Apple from a niche player in the low-growth and low-margin computer business into a consumer electronics juggernaut, putting the company at the center of a market approximately 30 times the size of its original market and fueling a decade of exceptional TSR. But now that Apple’s market capitalization is more than $500 billion, the company faces the difficult challenge of finding new areas of growth that can sustain its TSR trajectory. Current top-ten performer Tencent, which has increased its market valuation from about $39 billion to $183 billion in the six years it has enjoyed top-ten status, may face a similar predicament.

Active Portfolio Management: A Key to Sustainable Value Creation

The challenge of delivering strong and sustainable value creation has two critical implications for executives. First, as extraordinary as the performance of the top value creators is, it is important to keep in mind that for most companies, it may be more realistic to set a more modest target. A company can create a lot of value by delivering top-third or top-quartile TSR or by consistently beating the median of its peer group by a few percentage points per year—what in the 2015 Value Creators report we termed “value creation for the rest of us.”

Second, because a company’s future value-creation prospects are strongly influenced by its current position, executives should regularly reconsider their value creation strategy as the company’s position evolves, adapting the strategy to new circumstances and new industry trends. One of the most effective ways for a company to refresh its value creation performance is by actively managing its corporate portfolio—by defining the roles of the businesses, products, and other key assets in the portfolio, allocating capital and other resources according to those roles, among other things, and reshaping the portfolio over time through acquisitions and divestitures.