This is the third in a series of articles exploring what really matters for companies that collect and use consumer data.

Only about 20% of consumers say that they trust companies to do the right thing with their personal data, and more than half think that companies aren’t honest about their data use. Such mistrust translates into damage to a brand’s reputation and a quantifiable decline in revenue; consumers who perceive that a company has misused data will cut or curtail their spending with that company, as the previous articles in this series have shown.

Bridging the Trust Gap Series

- The Hidden Landmine in Big Data

- Why Companies Are Poised to Fail with Big Data

- How to Become a Trusted Data Steward

- Data Misuse and Stewardship by the Numbers

Consider the opposite scenario, though. Our research, which included surveys of companies and consumers, found that consumers are more willing to do business with companies they trust to manage their data. It stands to reason that as consumers decrease spending with companies they don’t trust, they will increase it with those they do. So, both to avoid the looming downsides of poor data use and to capture the upside potential of optimal data use, companies must be able to prove to consumers that they can manage data well. They must become trusted data stewards.

Few companies have attained that status. To do so, they must establish a set of best practices and work to embed a new mindset about consumer data usage: that companies themselves own the responsibility of ensuring that consumers and other stakeholders (such as regulators) fully understand the collection and use of consumer data. This article outlines the best practices required to achieve trusted data stewardship—both internally focused practices that define how a company collects, manages, and uses data and externally focused practices that establish how it engages with its stakeholders about its collection and use of data. Further, we have developed a diagnostic that companies can use to assess their progress relative to both competitors and state-of-the-art data stewardship benchmarks. (See “What Is a Trusted Data Steward? Where Does My Company Stand?”)

What Is a Trusted Data Steward? Where does my Company Stand?

A company that is a trusted data steward manages the collection of consumer data even before the collection occurs: Which data will we gather and why? How will we ensure that consumers understand and approve our data capture? Finely tuned management must continue, as the gathered data is properly stored, secured, and repurposed, always with transparency and adherence to policies and procedures that govern access, notifications, and permissions. A trusted data steward also stands ready to address any real or perceived misuses of consumer data, and it measures and shares its performance on all fronts.

We’ve developed an online diagnostic, The Trust and Data Privacy Best-Practice Tool. With this tool, companies can assess their data stewardship strengths and weaknesses and their performance versus industry peers. Answering a few questions will allow them to gauge their potential trust risk—and reward.

Internally Focused Practices

Becoming a trusted data steward begins at home; companies can establish—or enhance—best practices internally, in several ways.

Ensuring Engagement by Senior Line Executives. Senior line executives should be actively involved in establishing policies and principles. They need to determine overall policy and approve both legal-language and plain-language versions. Plain language matters—consumers would be 56% more likely to do business with companies that offer a short, clear, and easy-to-understand version of their full privacy policies. (See “ Bridging the Trust Gap: Data Misuse and Stewardship by the Numbers ,” BCG slideshow, October 2016.)

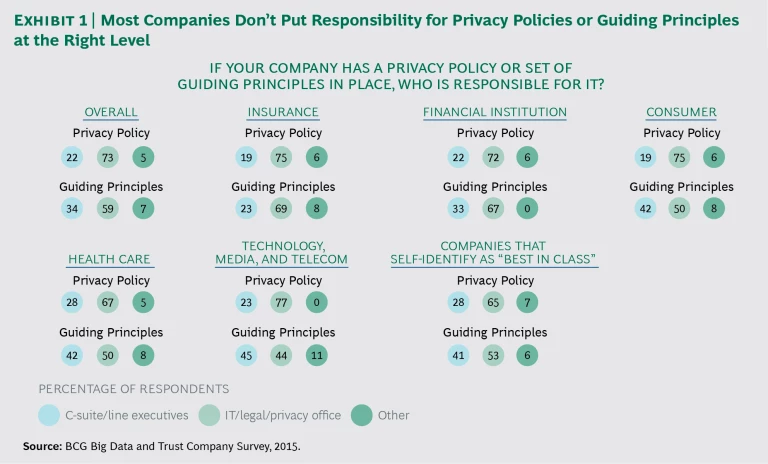

However, in most companies senior line executives are not substantively engaged in policy and procedure. Instead, responsibility is delegated to the legal and IT teams. (See Exhibit 1.) These teams should be involved, of course; they have the expertise to address legal and regulatory issues and cybersecurity. But the collection and use of consumer data directly affect brand value, market share, and revenue growth through consumer and stakeholder perceptions of these actions. So, these issues require active line guidance and decision making.

Consider the situation Google encountered when the news of Google Maps’ true scope emerged. While Google cars were collecting data for Street View, they were also grabbing data from home Wi-Fi networks, including passwords and e-mails, and creating individually identifiable consumer profiles. Google subsequently admitted that it should have informed consumers that it was collecting their data and using it to profile them—but an even greater shortcoming was revealed: senior executives were not aware of these activities; had they been aware, they likely would not have approved them.

Projects like this need the expertise that rests in multiple functions and at multiple levels of an organization. In this case, in the absence of either clear guidelines about new data collection and use or a decision-making framework that surfaced these new practices to the right, senior line levels, the decision to collect the data and create the profiles was made in isolation by the team doing the work. The backlash was provoked not by the project’s original intent—creating functionality for Google Maps—but by the collection of new data elements for new uses that were not specifically part of Google Maps and that had not been explicitly discussed and approved. Google has since limited its data collection approach, destroyed the profiles, and settled the resulting multistate lawsuit. But the kind of disconnect that led to Google’s issue is not uncommon in large organizations, demonstrating the need for clear guidelines and the active engagement of senior line executives in the governance process.

Creating Robust Protocols for Data Access—and Use. Once a company has established its policies, principles, and governance mechanisms, it must embed them in its approaches to regulating access to the data it has collected.

The good news is that many companies—71%, according to our survey results—have created protocols that govern access. These protocols establish which individuals have access to which particular types of data—the “who” and “what” aspects of the protocol.

But to truly steward data and avoid the pitfalls of unapproved uses, companies must also regulate the “why” aspect: the ways in which individual employees are allowed to use the data they are approved to access. Most companies do not have usage-based controls in place. They need to create protocols that consider “who, “what,” and “why” in order to achieve a well-rounded, purpose-based approach to data control.

The poster child for the problem of failing to control usage came into public view when Edward Snowden leaked classified information from the National Security Agency’s PRISM electronic-data-mining program. One of the issues that emerged was that people with appropriate access were, in the absence of usage-based controls, misusing data. Whether people agree or disagree with PRISM’s original intent—to defend against terrorism—and its extent, few would argue that the data collected should be used to intrude on a neighbor’s privacy or check up on a significant other.

In another example, from the corporate world, Uber took steps to better manage data after the revelation that its employees could access customer data and track customers’ location and that this data was being used for purposes far beyond providing outstanding car service. To mitigate such misuse in the future, Uber encrypted and password-protected location data. It also instituted a who-what-why approach to data access and use: the company restricts data access to a small number of employees, who can view and use the data related to drivers and customers only for legitimate business purposes.

Instituting Real-Time Monitoring and Proactive Responses. In a perfect world, everyone would follow the intent of guidelines, and purpose-based access protocols would work flawlessly. In the real world, it is important for companies to ensure that their employees are following the rules and that there are no violations of access or intent.

This requires supplementing access protocols with real-time data monitoring. Monitoring approaches must focus on the same who-what-why elements that access-based protocols must address: the individual accessing the data, the data that he or she can access, and the usage for which the data is being accessed. Currently, though, only one in five companies has any kind of real-time data-monitoring protocol in place, much less one that incorporates usage—meaning that more than 80% of companies are highly vulnerable to data misuse.

By building in ways to respond when employees improperly access and use data, a company can repair inevitable breaches before they do harm to their stakeholders and, in turn, to their own brand and financial performance.

Right now, data misuse (real or perceived) is usually uncovered through consumer or media scrutiny. External rather than internal discovery of misuse has two unfortunate consequences: the misuse continues for longer and has a more significant impact on consumers than if it had been identified and shut down before being built into widely distributed products and services. And when a company uncovers a misuse itself, its response can be managed internally instead of in the context of public scrutiny. As our research suggests, the implications of public reactions to data misuse are highly negative: company revenues fall by 5% to 8% in the first year after a real or perceived data misuse. We believe that the year-one loss could be more severe—10% to 25%—as consumer awareness and concerns increase. (See “ The Hidden Landmine in Big Data ,” BCG article, June 2016.)

However, it is unlikely that companies will execute perfectly to identify in advance all instances of data collection and usage that will ultimately result in adverse reactions from consumers or other stakeholders. So, companies must prepare protocols in advance so that they are ready to address these types of situations. Predefined actions to repair the specific collection and usage issues and to communicate effectively with consumers and other stakeholders will help ensure that companies emerge from these incidents with equal—or greater—trust rather than suffering brand and revenue erosion.

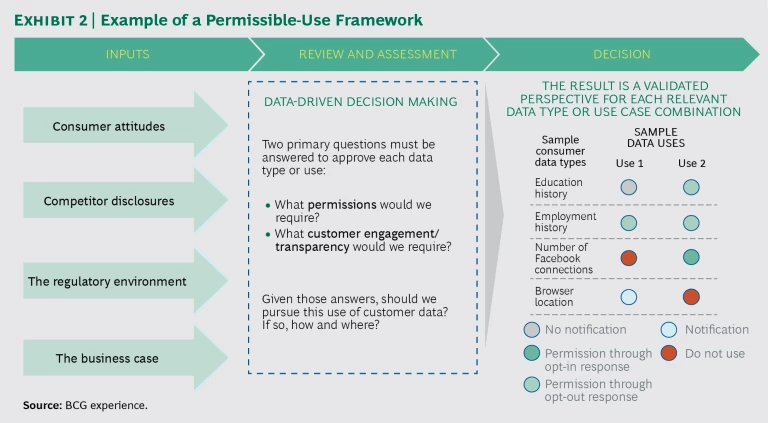

Establishing a Permissible-Use Framework. Designing new decision-making processes to evaluate and to approve or reject new uses of data is also critical. Best practices can be established by following a permissible-use framework, such as the one shown in Exhibit 2. Such a framework guides those contemplating a new data use to consider four key inputs:

- Consumer Attitudes. How will different segments of consumers react upon being made aware of this new use?

- Competitor Disclosures. Is this an innovative new use or is it already prevalent in the market?

- The Regulatory Environment. Is the new use allowable under current rules and agreements?

- The Business Case. What are the direct and indirect benefits to the company of this new use?

These four inputs allow executive teams to make a fully informed decision regarding the risks and value associated with potential new data uses. This perspective can help them to decide not only whether to approve or reject a new use but also how to extend their best practices externally—to determine the best approaches for engaging consumers and other stakeholders.

Externally Focused Practices

In addition to taking internal actions to reduce the potential for adverse reactions, companies must actively engage with consumers and other stakeholders through external best practices. These requirements of good data stewardship are as important as internal best practices—but more elusive. Currently, these are the biggest stumbling blocks and sources of failure for companies attempting to make use of consumer data.

Increasing Transparency. Our survey data is clear: consumers want to know what data companies are collecting and how it will be used. Such transparency is rare, however.

Ensuring a high degree of transparency is, for most companies, a major mindset and cultural shift. It is a shift from “making information available” and “adhering to legal requirements for disclosure” to something much more fundamental: being responsible for ensuring that consumers and all other stakeholders understand what a company is doing with personal data. This is a significant pivot, with inherent challenges—but companies face an additional barrier: the likelihood that the new transparency will engender negative near-term reactions from some consumers who are surprised by the existence of data practices that they perceive as new.

In the medium and long terms, however, the benefits of making this transition will be significant. Consumers are willing to accept a much wider use of their personal data than companies believe—but only if they are fully informed. In failing to understand and inform consumers, companies are currently being “recklessly conservative” (a behavior whose dangers we describe in the second article in this series, “Why Companies Are Poised to Fail with Big Data,” BCG article, October 2016).

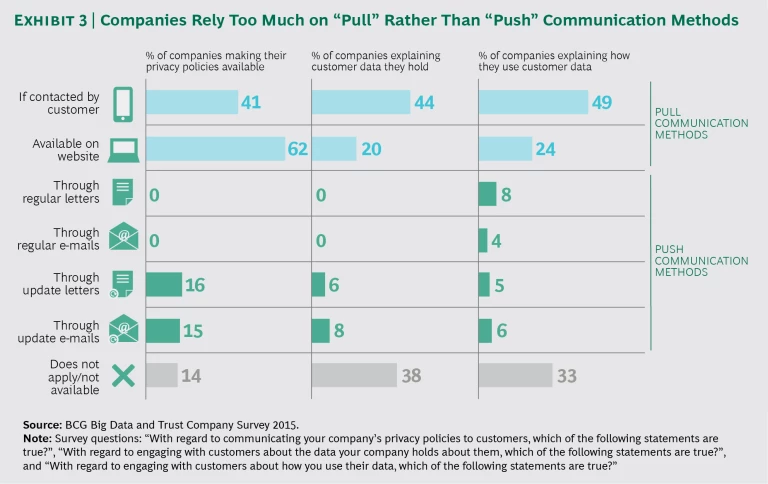

A successful transition from opaque to transparent lies in a adopting a new set of engagement practices—moving from “pull” to “push.” Engagement practices today are overwhelmingly oriented toward pull behavior. They are designed to support consumers who will take the initiative to investigate and understand data use practices. (See Exhibit 3.) Unfortunately, few consumers do so, leaving the majority primed for distress when they are unpleasantly surprised by “new” data activities.

Good pull practices should not be eliminated. Rather, companies should add push-based practices, by which they take the initiative to bring information to consumers’ attention. This requires designing the right communications messages, processes, and distribution formats and vehicles. The appropriate balance of push and pull methods will vary by company, industry, use case, or message. Always, though, a company’s core goal must be to ensure that its data collection and use are fully understood by all relevant consumers—and other stakeholders.

Indeed, transparency is not just a consumer issue. Making data practices clear to a wider set of stakeholders also creates significant benefits. Regulators need to know—in advance—when a company is doing something new so that their actions are not shaped as reactions to consumer and financial press, for instance. Investors, industry associations, and commercial partners will also benefit from such transparency.

Clarity and transparency are good for the entire “data use ecosystem”: when a company is open with regulators about its data practices, for instance, regulators are more likely to view new uses or consumer feedback positively because the transparency will provide them with valuable knowledge and insight into the complex and rapidly changing area of data usage and regulation. For example, we recently recommended that a financial services company implement a quarterly issues-oriented, non-transactional discussion with regulators. The goal is to give regulators a broad understanding of practices and issues on the horizon. Being involved in this way lets companies help drive the conversation instead of simply reacting to it.

Employing Purpose-Specific Notifications and Permissions. For each new use of data, a company should have an explicitly agreed-upon and purpose-specific approach to notification and permissions. In some cases, providing just a notification to consumers is sufficient. In others, an explicit opt-in response (which is not the same as signing a credit card application or clicking on a digital license agreement and thereby agreeing to something covered in the “fine print”) will be needed.

It is clear that companies need to do this more effectively.

For instance, The Global Privacy Enforcement Network surveyed more than 1,200 smartphone apps in 2014 and found that 85% did not disclose data uses and that many requested broad permission for data uses without explaining why or how the data would be used.

Measuring and Publishing Metrics About Consumer Trust. As with all significant change and key operating activities, progress toward becoming a trusted data steward cannot be made without active measurement. And, in the context of transparency, key metrics should be shared with consumers and other stakeholders. Doing so is a way to begin to differentiate a company’s data practices and create a sustainable competitive advantage.

Companies should start by creating metrics so that they can monitor trust, by tracking stakeholder perceptions, regularly and routinely. Metrics should be tailored to a company’s unique dynamics but should generally cover:

- Overall faith in a company’s data stewardship

- Willingness to allow the company to pursue new uses

- Understanding of a company’s data practices

- Areas of significant sensitivity and concern

These metrics will serve several functions. They will help determine how consumers are responding to current efforts and which approaches to notifications and permissions work best for particular consumer segments. They can feed into a permissible-use framework by revealing trends among different demographics. For example, trust data might indicate that millennials trust a company more than Generation-Xers do, indicating that opt-out permissions are a better methodology for the former group whereas opt-in permissions are more appropriate for the latter. Because they can deliver such insights, trust metrics can help senior executives set policy direction.

In general, this set of practices is the aspect of data stewardship that companies today are the furthest from mastering. Currently, only 6% of companies have internal consumer trust metrics and actively measure consumer trust, according to our survey, and just 4% publish their trust metrics regularly.

In the absence of these metrics, companies are flying blind. If you don’t know how you are being perceived, it is inherently impossible to know what to change. Thus blinded, a company will have little chance of becoming a trusted data steward and is in jeopardy of tripping unforeseen landmines and suffering reputational and performance damage.

The Responsibilities and Rewards of Trust

Companies must choose which direction to take when it comes to managing consumer data and trust.

Failing to establish good stewardship of consumer data puts companies on a vicious cycle, wherein poor management leads to the loss of trust and revenue and a downward trend in financial performance.

Conversely, companies can enter a virtuous cycle by establishing best practices and—crucially—a fundamentally revised mindset about privacy and data stewardship in order to win trust. In this virtuous cycle, managing consumer data well engenders consumer trust, trusting consumers allow more data to be used (our survey showed that consumers are at least five times as likely to share data with companies they trust), and so on.

Companies that choose this track and earn the trust of well-informed consumers will be able to create more value from consumer data. They can access more data for current uses and pursue new uses that are not available to less-trusted competitors. This advantage, we believe, is sustainable, because the capabilities that must be built to achieve it are not easily replicated and because standards will only get higher over time, allowing front-runners to get far ahead of the pack as they establish new marketplace norms.

The choice seems clear, and the time to make it is now.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights .