There’s a schism in the investment universe. Large funds and, increasingly, institutional investors are actively engaging with the management teams of companies in their portfolio to improve governance, operations, and other aspects of a company’s performance in order to create more value. Yet when it comes to dealing with a company’s performance as gauged by environmental and social metrics, many of the same investors either sell off holdings that don’t meet their environmental or social requirements, or avoid buying those companies in the first place.

Although divestments and exclusions are necessary tools for responsible investing, they are not sufficient. Capital can generate greater societal good when investors directly engage with a portfolio company’s management team to trigger changes in environmental sustainability, diversity, or other objectives. In addition, such changes may help improve financial performance.

This is not a new concept. It’s merely a new application of what many investment professionals do every day. Institutional investors have the economic clout and credibility to meet with management teams, ask the right questions, and press for strategic and operational improvements. They can adopt the same practices to improve a company’s performance on environmental and social metrics.

The Rationale for Engagement

The market for responsible investing was nearly $23 trillion as of 2016—up from $18 trillion in 2014—accounting for more than a fourth of all managed assets. That major expansion reflects heightened interest on the part of investors in putting their capital to work doing good while earning returns, together with a growing belief that these objectives are compatible. Stakeholders such as public institutions, endowments, universities, successful entrepreneurs, and other customers of institutional investors are far more likely now than in the past to demand responsible investing strategies. And in the ongoing competition for talent, such policies are a valuable differentiator. Employees—particularly younger ones—gravitate toward organizations that have identified and work toward a clear purpose beyond simply making money. (See Purpose with the Power to Transform Your Organization , BCG Focus, May 2017.)

Moreover, research suggests that a company’s performance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics correlates with its financial performance. A recent BCG analysis of more than 300 companies in five industries—consumer packaged goods, biopharmaceuticals, oil and gas, retail and business banking, and technology—found that for companies with strong ESG performance, valuation multiples and profit margins were measurably higher and risk was lower. (See Total Societal Impact: A New Lens for Strategy , BCG report, October 2017.)

But what is the best way to combine responsible investing with encouraging portfolio companies to improve their ESG standing? Many institutional investors emphasize divestments and exclusions in their approach to responsible investing, essentially making a thumbs-up or thumbs-down decision about a particular investment on the basis of its ESG scores.

Divestments and exclusions do send a signal to management teams and the capital-markets community that capital is less readily available to companies that disregard ESG measures. These actions can become even more effective when groups of institutions and investors develop specific standards for triggering them. For example, the CERES Investor Network on Climate Risk and Sustainability counts more than 130 institutional investors—including firms such as BlackRock, State Street Global Advisors, and TIAA—that oversee more than $17 trillion in assets.

Unfortunately, when investors focus entirely on divestments and exclusions, they effectively opt out of trying to solve the issues targeted by their screen, ceding that responsibility to others that may or may not try (or be able) to address them. A responsible investor may maintain a pristine portfolio by parking its capital on the sidelines, but in practical terms this amounts to declining to participate in the effort to promote greater social good.

In contrast, when investors directly engage with the management teams of companies in their portfolio—particularly those that might not clear an ESG screen—they can press for changes that improve the companies’ performance on ESG factors such as greenhouse gas emissions, rather than retreating from the issue.

This kind of engagement can have a multiplier effect. Consider an institutional investor that wants to reduce carbon emissions. It could simply avoid investing in retail companies with large, carbon-heavy supply chains, and thus claim to be doing good by maintaining a greener portfolio. But if that same investor worked directly with the management team of a retail company on ways to reduce emissions, the environmental gains would accrue not only to the carbon quotient in the investor’s portfolio but also to other stakeholders, to the company’s customers, and to society at large.

How to Implement an Engagement Strategy

Direct engagement calls for a more complex strategy than simply divesting holdings or excluding them from the portfolio, but the potential gains in employee engagement, shareholder value, and societal impact are larger, too. To succeed in these efforts, institutional investors need to adopt a structured approach. In our experience, the following measures are critical.

Build an integrated approach to ESG assessment. Investors can begin by taking stock of where and how they use ESG factors throughout their investment process. The goal is to build a comprehensive ESG approach based on sector-specific metrics. The most relevant ESG factors for manufacturing companies in the portfolio might be water and waste management, raw materials sourcing, and energy usage. For mining companies, the key factors might be biodiversity and land use. In any event, an investor’s ESG approach should be a core component of its overall risk management framework, and not a side topic run by a separate team that focuses exclusively on ESG.

Define priorities for engagement. Investors should determine which ESG factors to prioritize with the management teams at portfolio companies. These factors should link to specific interventions that investors believe could materially improve ESG performance—for example, measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions at companies that have extensive, wide-ranging supply chains.

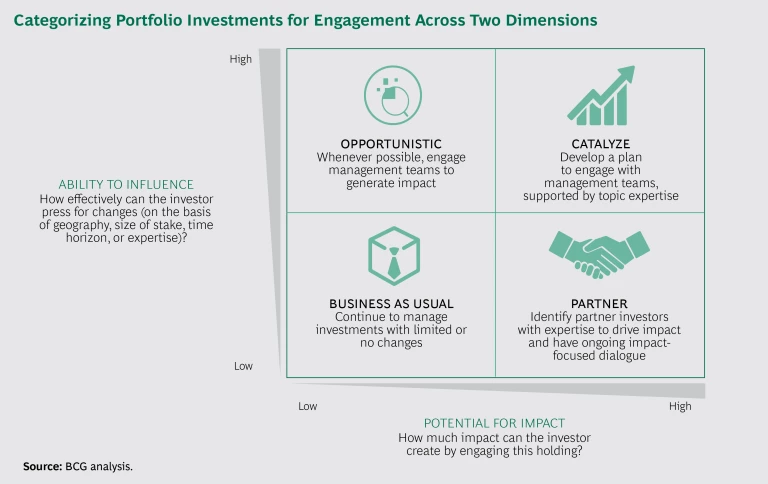

Categorize portfolio holdings. To determine which companies and assets are the best candidates for engagement, investors should rank them along two dimensions: investors’ ability to influence management to make changes, and the potential impact of such changes. (See the exhibit.)

Develop a plan for engagement. Not surprisingly, different clusters of investments require different approaches. For the highest-priority situations—those in which investors have significant influence over a company and in which engagement can yield a large potential impact—investors need a plan for engagement. Management teams at portfolio companies are far more open to these discussions today than they were in the past, and investors that start with the goal of creating a dialogue, hearing management’s point of view, and offering access to technical expertise can create more collaborative partnerships.

In developing a plan for engagement, investors should conduct due diligence to understand the company’s capabilities and its existing ESG initiatives. Investors should also build their expertise in a given topic, perhaps by hiring people and empowering them to engage with portfolio companies. (In some cases, investors can increase their expertise on a topic by forging partnerships with other organizations.)

Set up systems to track ESG progress over time. Just as they do when dealing with financial returns, investors must scrutinize the ESG performance of their holdings over time. For example, submitting questions to management about ESG performance must become a routine part of investor calls and management reporting. By developing this disciplined approach to quantitative assessment, investors can gain greater insight into the links between a company’s performance on material ESG measures and its financial performance. And as in other areas of investment, differentiated insight can improve capital allocation and risk management.

Be willing to divest. If portfolio companies fail to make progress toward the objectives of the investor’s ESG strategy and engagement goals, the investor should consider selling the position, following a clear and explicit discussion with management about why that step may be necessary.

Pilot, test, and learn. Because the engagement approach is new to many institutional investors, they should adopt a mindset of experimentation and continuous learning. Rather than trying to craft the perfect approach, they should first develop a working model for engagement and test it with a small number of portfolio companies, and then refine the process as they scale it up across the portfolio.

Spread the word. Finally, investors that succeed in both dimensions—improving financial performance and putting capital to work to drive societal change—should publicize their efforts. Communicating with the media, with their own clients, and with other organizations that focus on related social or environmental concerns can help investors stand out in the market, generate new deals, and build further momentum for socially responsible investing.

For firms that want to invest responsibly, engagement with the management teams of companies in the portfolio is a valuable tool that can complement divestment and exclusion strategies and lead to greater social impact. This approach is a logical extension of the work that institutional investors and private equity funds increasingly do to improve the financial and operational performance of their portfolio companies. The only thing new and different in this case is the impact that capital will have in making the world a better place.