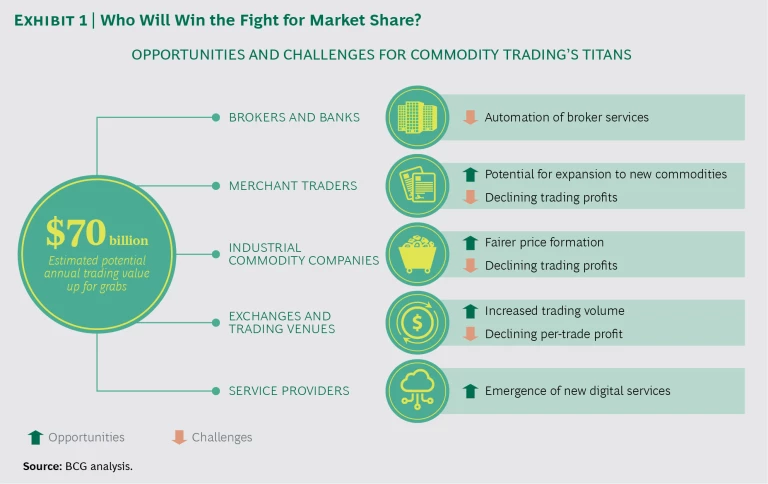

Digital forces are changing the way commodities are bought and sold in the marketplace. And this trend is transforming the commodity-trading value chain and redefining sources of competitive advantage, redistributing as much as $70 billion in trading value in the process.

In this third in a series of articles on the impact of digitalization on commodity trading, we explore the forces that are altering the power balance among the industry’s titans: brokers and banks, merchant traders, industrial commodity companies, exchanges and trading venues, and service providers. We also identify steps that these players can take in response to the challenges they face and discuss emerging sources of competitive advantage.

More from this series: Digitalization in Commodity Trading

- Hyperliquidity: A Gathering Storm for Commodity Traders

- Attack of the Algorithms: Value Chain Disruption in Commodity Trading

- Capturing Commodity Trading’s $70 Billion Prize: How Digitalization Is Changing Commodity Trading

Changing Market Dynamics

Commodity traders make profits by monetizing market imperfections, including those related to quality, time, and location. The value of a given trade is determined by the size of the imperfections minus the trader’s “friction costs” of infrastructure, handling, and other operating expenses. On the basis of our analysis of world commodity flows and typical trader margins and operating expenses, we put the industry’s potential annual value pool today at $70 billion.

As the various commodity markets move toward hyperliquidity (the state in which a market’s efficiency and transparency are at their highest possible levels), the pie shrinks. But the prize remains substantial. Who will win the new fight for market share? (See Exhibit 1.)

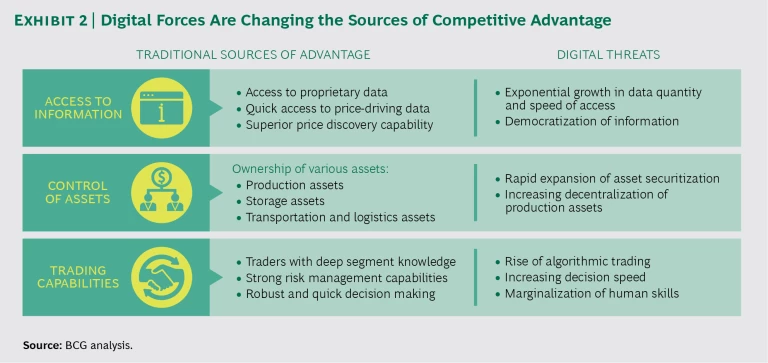

In recent years, the industry’s profits have been shared among five major groups of players: brokers and banks, merchant traders, industrial commodity companies, exchanges and trading venues, and various service providers. The profit proportions have been determined by the groups’ respective abilities to leverage the industry’s traditional sources of competitive advantage: access to information, control of (or access to) assets, and trading capabilities.

As digitalization advances, however, and as more commodity markets (European gas and power markets, for example) approach hyperliquidity, the sources of competitive advantage are changing. (See Exhibit 2.) Information is becoming more vast in scale and scope and, simultaneously, more widely available. Thanks to asset securitization and the decentralization of production assets, such as power plants, various players are finding it easier to gain access to, and control of, assets. Trading capabilities, traditionally based largely on human skills, are evolving rapidly and are increasingly characterized by algorithm-based decision making, which uses advanced analytics. And the technology underpinning these new trading capabilities is becoming more widely available.

The upshot is that incumbents’ established business models are becoming less and less relevant.

Compounding the challenge for these companies, new competitors, most notably service providers, are entering the arena. The newcomers further alter the competitive terrain and could materially change the industry’s balance of power.

Each of the five groups of players faces its own challenges and opportunities. Within each group, some firms could weather the storm and thrive; others could see their businesses fundamentally disrupted.

Brokers and Banks. The traditional business model employed by brokers and banks, which focuses on providing market access and liquidity to clients and on using information to the company’s advantage, is at the frontline of disruptive change. Brokers, such as Clarksons and Global Coal, are typically independent and offer liquidity and financing to customers by connecting buyers and sellers; these companies do not, themselves, take positions in the market. Banks that operate commodity desks, such as Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase, provide market access and financing. In markets that are more liquid (crude oil, for example), they often offer risk management services.

Digital forces will put growing pressure on these businesses by ushering in several significant challenges:

- Fewer Conventional Transactions. The volume of conventional, human-processed transactions (such as phone conversations with a broker) will drop as more market players abandon these activities in favor of electronic platforms and direct market access.

- Pressure on Fees and Margins. As the service- and data-provision landscape continues to open up, more players will enter the competitive fray. Digital pure plays will offer services at considerably lower cost than traditional providers, challenging traditional players’ margins. This trend is already well underway; digital platforms, often owned by traders and marketers rather than brokers, are quickly proliferating.

- Dis-Integration of Services. Banks’ traditional “white glove,” end-to-end service offering (including data provision, market analysis, risk management support, financing, and trade execution) will fall from favor as customers increasingly opt to purchase discretely available services, which will become more prevalent.

- Greater Complexity in Funding. As their sophistication increases, more and more market participants will become sensitive to the cost of funding. Many industrial commodity firms, for example, have put offers of trade financing out for competitive bids and thereby reduced their financing costs. Aggressive use of repurchase agreements for inventory financing is an example.

- Changing Talent Demographics. As the use of complex analytics becomes more important to the trading industry, the types of human resources needed—and the client demands that brokers must respond to—will change. The industry is likely to employ more people with advanced degrees and fewer traditional tie-and-suspenders analysts.

- Increased Regulatory Pressure. The cost of complying with increasingly complex regulatory requirements, such as Dodd-Frank, has weighed heavily on banks and brokers. The complexity and number of such requirements will likely continue to rise as regulators across markets seek greater transparency and liquidity.

We already see the effects of these challenges. Multiple commodity trading desks at these businesses have closed in recent years, and the closings seem likely to continue unless banks and brokers rethink their value proposition. To remain in the commodity business, banks and brokers will probably need to add services and other value-creating elements to their offerings. They could, for example, support algorithm-based trading, consult on hedging strategies, or offer structured products through digital platforms.

Merchant Traders. Merchant traders such as Vitol, Trafigura, and Cargill operate as optimizers of commodity flows between suppliers and end customers. They create value through their ability to access critical assets, blend or disaggregate products or product elements, collect proprietary information, manage financing, and connect market players through their global reach.

Merchant traders have been quite agile in adapting to changing market environments in the past. Their traditional competencies and edge in information created a winning recipe. As digitalization marches onward, however, we see a number of challenges for them:

- Ongoing Reductions in Market Imperfections. As digitalization of trading increases transparency and trading speed, the number and extent of market imperfections will shrink, compressing margins on individual transactions.

- An Expanding Playing Field. Goods and services that have not been considered commodities (such as hard-disk drives, digital advertisements, and generic pharmaceuticals) are becoming commoditized, enlarging the playing field for merchant traders. At the same time, trading volumes of some key commodities are increasing as a result of globalization and a move in some markets (natural gas, for example) from long-term agreements toward spot trading. This movement, in turn, is leading to greater amounts of information about these commodities in the market and reducing the opportunities for merchant traders to gain advantage through proprietary information.

- Reduced Advantages of Asset Ownership. Many merchant traders have acquired physical assets, such as refineries, mines, storage capacity, and logistical assets. This ownership has often conferred sizable advantages to these companies in the form of increased information flows and greater physical flexibility. The growing availability of information and virtual assets, however, allows companies to gain many of the advantages of physical ownership at lower cost and reduced operational risk. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange, for example, now allows trading in securities representing physical oil storage. This ability, and the greater insight into the value of storage that results, makes many of the advantages once held by merchant traders that owned storage capacity (for instance, the ability to arbitrage between oil forward contracts and storage value) available to any trader.

- New Market Entrants. The arrival of new players (for example, hedge funds) that can offer a host of services, such as data provision, analytics, financing, access to assets, and algorithm-based trading execution, brings tough competition for traditional merchant traders. On the other hand, it gives them the opportunity to gain capabilities through partnership with these new entrants.

- Changing Talent Demographics. As with brokers and banks, the type of talent that merchant traders need is changing. Traditionally, the greatest competitive advantage came from hiring people with commercial capabilities; in the future, merchant traders will likely put more weight on hiring data scientists who possess strong quantitative and digital skills and can identify opportunities across asset classes.

To negotiate the new environment, merchant traders will need to continue their history of agility and adaptation. This time, however, the changes they face are likely to come much more quickly, putting a premium on flexibility and speed.

Merchant traders will need to find ways to create proprietary information flows—for example, by partnering with suppliers and inserting information-gathering sensors in suppliers’ value chains. They will also need to make greater use of algorithm-based analytics and the trading of securitized assets. This will necessitate cross-commodity analytical platforms, which many merchant traders do not have. Merchant traders must also place greater emphasis on risk management, which becomes increasingly important as the market accelerates and the correlations between asset classes (between equities and commodities, for example) change.

Merchant traders should not discount the threat that digitalization poses. In many markets, logistical bottlenecks and inherent differences in commodities’ physical qualities and credit risk profiles make the incursion of digitalization seem a distant possibility. But signs of digitalization are already apparent in some of the most illiquid markets. Digitalization can fundamentally change merchant trading’s business model, both by aiding traders and, eventually, by replacing large segments of human-based analytics and trading. Merchant traders must recognize this possibility and prepare to respond with new competencies.

Industrial Commodity Companies. Industrial commodity companies, such as mining players BHP Billiton and Anglo American, oil companies Total, Shell, and BP, and utilities Vattenfall and Uniper, are cornerstones of the global industrial landscape. They operate in all parts of commodity value chains, from upstream production to transformation and distribution. Some of them have also built significant trading and marketing arms. These companies are thus fully exposed to the forces affecting the commodity-trading landscape.

As digitalization makes markets more efficient, these companies will benefit from fairer price formation and increased transparency. Many industrial commodity players that have built value chain optimization and trading arms, however, will come under increasing pressure from digital technologies. The challenge is likely to play out across a number of dimensions:

- Less Time for Decision Making. Historically, arbitrage plays took some time to complete. The trader would observe the market, calculate a position, get the necessary approvals, and call a broker to execute the strategy. But digitalization is shrinking the time available for decision making. Near-real-time algorithms constantly scan markets for inefficiencies and exploit them instantly.

- Increasing Need for Direct Market Access. In the past, brokers and banks acted as middlemen for industrial players. Markets’ rising speed and efficiency requirements, however, are pressuring industrial players to create direct access for themselves.

- Reduced Advantages of Asset Ownership. As noted earlier, the advantage of owning an asset—one of industrial players’ traditional strengths—is eroding as asset securitization and the availability of information grow. Some industrial players will also struggle as they transition from managing a few large assets (nuclear plants, for example) to managing multiple smaller ones (such as decentralized solar assets), a change that brings with it the challenge of adapting to electronic aggregation platforms. Simultaneously, as the value of assets becomes more explicit thanks to market pricing of securities and the availability of efficient valuation tools, industrial traders will find new opportunities. Many global shipping companies, for example, participate in alliances that make idle capacity at other shippers part of their own available capacity. Such opportunities will change the nature of asset ownership.

- The Need for Greater Efficiency. As industrial commodity companies’ profits come under pressure, the companies will need to become more efficient. Achieving this will entail difficult actions, such as replacing some personnel in basic operations (including back-office operations, data management, hedging, and basic analytics) with automated processes. Many players currently employ people to handle delta hedging of storage, for instance. In liquid markets, such activities can increasingly be performed more cheaply, more quickly, and with greater precision by robots.

To maintain their profitability in the face of these forces, industrial players will need to assess their position in the trading value chain. Which parts of the chain should they own themselves or with a partner, and which parts should they outsource? These companies will also need to become even more digitally integrated—by digitalizing their information flows and steering processes, for example, to enable their physical assets and supply chain to adapt in real time to changes in the market, including changes in commodity prices.

Exchanges and Trading Venues. Commodity exchanges and trading venues operate platforms that allow players to trade securities. Exchanges such as the Intercontinental Exchange and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange handle trades that are governed by standardized contracts. The exchanges match trades automatically, often using limit-order techniques. Participants don’t know who is on the other side of their transactions, and the trades are cleared, which eliminates counterparty risk. The platforms offered by generic trading venues, such as Trayport, handle trades that are governed by less standardized, over-the-counter (OTC) contracts.

Driven by digitalization, the volume of electronically traded commodities is steadily increasing, and this trend will likely lead to a number of changes for exchanges and trading venues:

- Increasing Importance of Clearing in OTC Trading. As the number of new contracts continues to increase owing to securitization, and as regulation mandates ever-greater transparency in derivatives trading, market participants will show a growing preference for cleared trades, as we saw in the development of OTC trading related to central European gas. Platforms that offer OTC trading with integrated clearing services will likely attract a steadily rising volume of business.

- A Shift from OTC Trading to Exchange-Based Trading for Mature, More Liquid Commodities. Trading of mature, more liquid commodities will increasingly move from OTC trading to exchange-based trading. The strength of the shift will depend on the size of the benefits—for example, greater liquidity, more efficient infrastructure, lower costs—that the exchange can offer relative to cleared OTC trading.

- Rising Infrastructure and Service Needs. As the number of trades increases and the average time between trades falls to milliseconds, enormous stresses will be placed on the infrastructures of platforms and exchanges. Physical exchanges, in particular, will need to make sure that their IT infrastructure is up to the task. In addition, as OTC platforms continue to add services, such as execution algorithms, exchanges must expand their portfolio of services to keep pace with the competition.

To cope with these changes, commodity exchanges and trading venues need to find ways to adjust their commercial model to create additional revenues and attract liquidity. Possibilities include services such as co-location (that is, placement of a company’s computers that contain its trading algorithms next to an exchange’s matching engine to enable faster trading) and direct, ultra-quick feeding of price data, and new business models, such as the “rebate” systems that trading platforms have introduced to boost liquidity in the trading of equities. Platforms and exchanges will also need to invest in IT architecture that can keep up with the demands that arise from greater volume and rising performance standards.

Service Providers. Historically, most commodity trading firms maintained their own in-house value chains, so they owned the customer interface, data, systems, traders, and back-office functions. However, as discussed in our previous article, such end-to-end ownership of the trading value chain has become less common. Specialist service providers, such as Quandl, Contix, and Likron, are changing the value chain’s economics—and capturing a growing share of the prize.

These newcomers offer specialized data, algorithmic expertise, processing capacity, and other types of digitally enhanced services. Their offerings have the potential to further enhance the trading value chain’s efficiency, profitability, and costs—and to further undermine the economic logic of a single trading firm’s owning and operating its own end-to-end value chain. The newcomers also pose challenges to established service providers.

Although most of these new service providers are still expanding and exploring their operating space, it is clear that their growth prospects are sizable. Growth potential stems from several digitally driven factors that are affecting incumbents (namely, brokers and banks, merchant traders, industrial commodity companies, and exchanges and trading venues):

- The Potential for Greater Optimization of the Operating Environment. Digital technologies and increasing standardization have the potential to quickly reshape the operating environment along the entire value chain. Emerging service providers can help incumbents seize the resulting opportunities. New service providers are already making inroads through the development of offerings related to back-office automation (based on robotics and straight-through processing) and trade execution (based on algorithms).

- Growing Pressure to Reduce Costs in the Face of Falling Trading Margins. As margins fall, incumbents face a growing need to reduce costs. New service providers can help them do so through offerings that automate manual and basic tasks, such as trade execution. Several incumbents, for instance, have already outsourced their trading of intraday power to Likron, a specialist in algorithmic trade execution.

- The Need for Streamlined, More Efficient Governance and Execution. Many incumbents find themselves saddled with complex governance processes that result in long decision-making times. Rather than trying to address this issue with in-house resources, incumbents can avail themselves of the digitally enabled offerings of new service providers. Contix, for example, has a platform based on machine learning that can help companies evaluate opportunities on social media.

- The Opportunity to Access Transparency on the Cheap. Traditional information providers, such as Bloomberg and Reuters, and price-reporting agencies, such as Platts, OPIS, and Argus Media, built their models around the collection, standardization, and analysis of data. New service providers, leveraging digital technologies, give customers access to the same data and services at lower cost. Quandl, for example, aggregates and evaluates financial, economic, and alternative data; Natixis, IBM, and Trafigura have blockchain-based offerings that provide data and related services to support global trade in crude oil.

Traditional service providers will still find opportunities in this rapidly evolving environment. But they need to reassess their value proposition in the face of the new challengers and continue to expand their use of digital technologies if they hope to keep pace.

Changing Sources of Competitive Advantage

As digitalization redefines the commodity-trading value chain and puts cracks in existing ways of doing business, the requirements for success are changing. To win in this environment, competitors need to retool and reshape themselves across all three traditional sources of advantage:

- Access to Information. Digital technologies enable companies to access and digest a growing mountain of increasingly complex data. Players must invest to increase their access to data and data-processing capabilities.

- Control of Assets. As the value of asset ownership diminishes, a more nuanced set of models for accessing and controlling assets is emerging, along with changes in how assets are valued and financed. Competitors must embrace the new asset access models and understand how they change a company’s capability needs.

- Trading Capabilities. The historical practice of trading by intuition, supported by limited analytics, is being replaced by more systematic, machine-based trading that utilizes algorithms to support the collection and treatment of information and the decision-making process. Competitors will need to invest in the necessary infrastructure and in personnel who focus on software development and mathematics.

The commodity-trading arena finds itself at a crossroads. For most players, making the changes necessary to remain competitive will be a tall order, but the task is ultimately achievable—and critical to success. In the next and final article in this series, we will expand on the capabilities various players need and discuss the opportunities they have to strategically reposition themselves.

For the first two articles in this series, see “Hyperliquidity: A Gathering Storm for Commodity Traders,” BCG article, November 2016, and “

Attack of the Algorithms: Value Chain Disruption in Commodity Trading

,” BCG article, January 2017.