Do tech deals add value? With median EV/sales multiples well above historical averages, and total deal value in 2016 almost on par with that of 2000, right before the dot-com collapse, it’s a good time to ask if shareholders benefit from tech-driven M&A.

The 2017 M&A Report

- The Technology Takeover

- The Resurgent High-Tech M&A Marketplace

- Doing Tech Deals Right

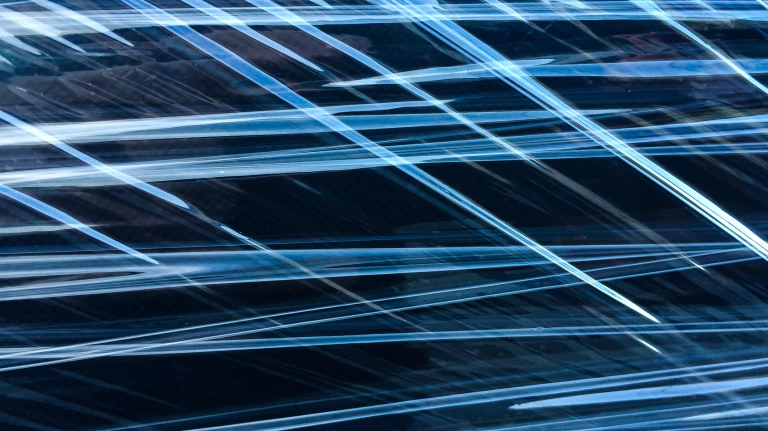

The answer is… it depends. We analyzed the announcement returns of more than 37,000 tech acquisitions and found that, overall, such deals are actually a 50-50 gamble. About half of deals involving a technology target (51%) generate positive cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) at announcement—about the same percentage of deals with positive CARs for acquirers in all transactions. (See Exhibit 1.)

At the same time, we found no material difference between tech buyers acquiring targets in their own industry (51% of these deals have positive announcement CARs, with an average of 0.53%) and buyers from outside the tech sector doing tech deals (51% have positive announcement CARs, with an average of 0.47%). These findings do not materially differ from the market’s reaction to other M&A transactions.

This brings us to a second, equally important, question: can acquirers shift the odds in their favor? Our research and our client experience suggest that they can, but there are a number of factors to consider.

Strategic Considerations

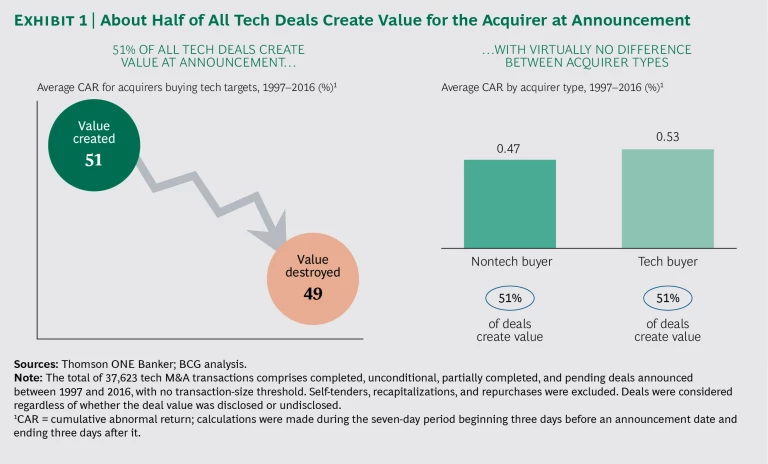

Since M&A can be risky, acquirers should consider their goals carefully. Transformational billion-dollar deals are particularly tricky. As we highlight in a related article from the 2017 M&A report, “The Resurgent High Tech M&A Marketplace,” lofty valuation premiums of 50% to 80%, often driven by bidding wars for must-have assets, heighten the hazards. Investors take a wary view of such transactions, at least until they prove out, and their wariness increases with transaction size: on announcement, deals worth more than $1 billion yield a negative CAR (on average, -0.33%) compared with a positive CAR (averaging 0.81%) for deals worth less than $1 billion. (See Exhibit 2.)

While managements often see acquiring a minority stake in a tech enterprise as a way of moving cautiously into new areas and mitigating risk, investors tend to reward companies that take matters into their own hands. Deals in which the buyer takes control of the target create, on average, higher CARs (0.78%) than minority interest transactions (0.01%). Investors are concerned that corporate minority owners lack the position and resolve to fully exploit the target’s technology and thus fail to realize synergies. Disagreements with other investors can get messy, and minority holders may not have the ability to take decisive measures when things go wrong.

Experience Counts in the Longer Term

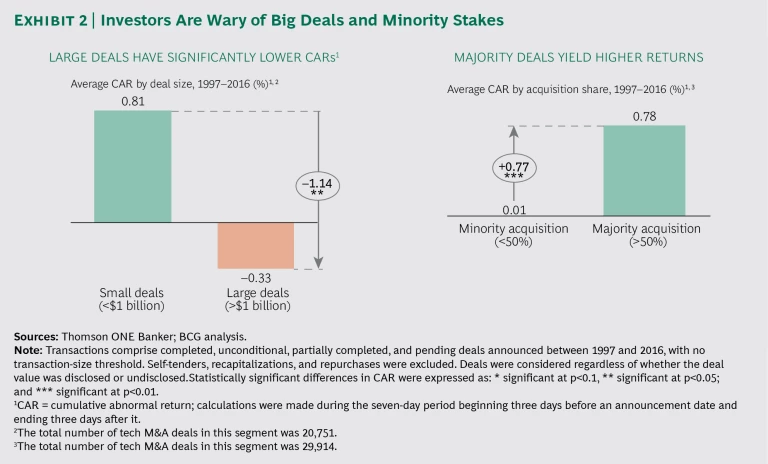

It may seem counterintuitive, but the market rewards first-time tech acquirers—and it rewards them more highly than experienced dealmakers. (See Exhibit 3.) Inexperienced acquirers earn the largest short-term returns at announcement because investors often see a company’s first tech acquisition as an indication that the company understands the need to transform, recognizes a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, or is forming the nucleus of a shift in business model toward more innovative products or services. The average market capitalization of one-time acquirers in our sample is $5.4 billion, and the 1.04% CAR that they achieve on announcement equals a net gain of approximately $60 million—simply from announcing an acquisition with an average deal value of about $200 million (which represents a 27% announcement return). Frequent buyers of tech targets (firms that completed two to five deals over a ten-year horizon) also achieve a significant positive CAR, 0.90%, while the CAR for serial tech acquirers (those that completed more than five tech deals over ten years) is much lower, only 0.37%. This could be because investors consider a tech acquisition for this type of firm as part of the company’s ongoing business strategy, therefore constituting a less significant corporate event.

One year after announcement however, a different picture emerges. Neither one-time acquirers nor frequent buyers outperform the market, while serial tech-target acquirers outperform the relevant index by 4.4 percentage points. This holds true for acquirers in both the tech and nontech sectors.

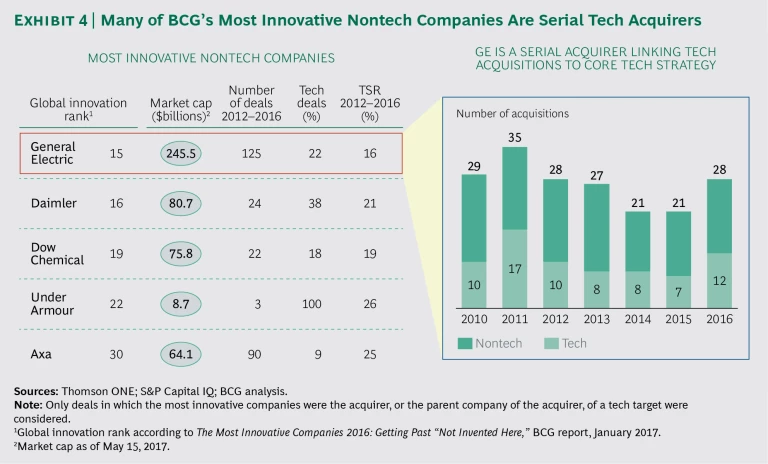

We have written before about the advantages that serial acquirers gain from experience in sourcing, executing, and integrating acquisitions, and it appears that the benefits of experience extend to tech deals as well. (See, for example, The 2015 M&A Report, BCG report, October 2015, and “Unlocking Acquisitive Growth: Lessons from Successful Serial Acquirers,” BCG Perspective, October 2014.) Indeed, many of the companies in BCG’s annual ranking of the world’s most innovative companies are serial acquirers of both tech and nontech assets. (See Exhibit 4.)

Some companies—such as General Electric, Daimler, Dow Chemical, Under Armour, and Axa—use tech M&A as a core component of their innovation strategies. Over the past five years, for example, General Electric executed 125 acquisitions of which more than 20% involved tech targets, including industrial internet front-runners Bit Stew Systems and Meridium, as well as a string of small to midsize deals that have helped build GE’s digital platform.

Three Keys to Unlocking Value

Successful tech acquirers do three things right: they follow an explicit and focused strategy, they develop a tailor-made M&A process for tech targets, and they build the right corporate organization to find, execute, and integrate innovative tech targets.

Tech Deal Strategy. Successful digital buyers combine four best practices into a coherent strategic approach for tech deal making. First, they look at tech M&A as an integrated part of their strategic arsenal; deals are part and parcel of doing business, not appendices or pet projects. These companies have ongoing strategic processes that include discussions of tech M&A targets as part of advancing their core business portfolio.

Second, tech M&A complements their in-house innovation work and R&D. These companies don’t treat tech acquisitions as a substitute, or one-time remedy, for an aging product portfolio. Acquisitions form only one pillar of a clearly articulated technology transformation plan, and these companies have an underlying organizational structure for integrating and supporting acquisition targets.

Third, tech M&A is governed by a customized, and often very lean, structure to facilitate the speedy execution of tech deals. These companies recognize that tech M&A differs from traditional M&A in certain respects, such as the need for shorter due diligence time frames and for key decision makers to be involved early on.

Finally, these acquirers are flexible in the way they structure and execute deals. They are willing to pursue alternative deal structures, such as minority investments, earn outs, and stock options that enable targets to maintain their entrepreneurial culture and incentives, even within large corporate structures. Perhaps more important, smart buyers also look at the deal from the target’s point of view. They understand that success ultimately requires effective collaboration extending through the transaction process and beyond, and that this means developing an understanding of the business model and cultural drivers of an organization very different from their own. (See “Understanding the Target’s Perspective.”)

Understanding the Target’s Perspective

Understanding the Target’s Perspective

Traditional companies and tech firms have plenty of differences. Business models, cultures, organizations, metrics and compensation schemes, and ways of working are just a few. The match between large, often bureaucratic corporations in traditional industries and nimble, fast-moving startups often appears ill-conceived. Yet in 2016, more than 8,800 tech firms found new owners or major investors, approximately 70% of which were outside the tech sector.

Tech startups often have specific reasons for selling to a nontech buyer that go well beyond the financial aspects of the transaction. (See “What Deep-Tech Startups Want from Corporate Partners,” BCG article, April 2017.) In our experience, the acquirers that make the effort to understand what their targets are looking for and how they see the fit with their new parent gain a big leg up in making the acquisition work. Considering the following questions before embarking on a tech transaction can help set acquirers’ expectations with the prospective target and smooth the M&A process and postdeal transition.

Why do so many tech companies sell to buyers from other sectors? Money is one reason, of course. Founders and their backers often want to cash in, and in many instances, nontech-industry buyers are often the ones that are willing to write the biggest checks. But multiple other factors come into play as well. Industry veterans provide access to existing products and services that the technology firm would hardly be able to build out on its own. Established companies from outside the tech sector can provide access to new markets through the acquirer’s core product line. Cruise Automation, for example, was able to deploy its autonomous-driving technology overnight through GM’s global vehicle base rather than retrofitting cars one by one.

Buyers from other industries also give targets access to an established customer base, enabling the target to leapfrog in sales growth. When Walmart acquired Jet.com, for example, Jet.com gained access to the fast-growing e-commerce marketplace run by the world’s biggest brick-and-mortar retailer and added muscle to compete with such internet retail giants as Amazon.

Nontech partners provide the trust and brand recognition of an established major industry player. This enhances the target’s visibility and reputation as a reliable business platform. For instance, brand recognition for the app mytaxi rose with the first investment by Daimler in 2013, and today, mytaxi is the world’s most successful taxi intermediary, with more than 10 million downloads.

What do tech companies expect in the M&A process? Agreeing on a deal can be complicated by the different perspectives that buyers and startups bring to the negotiating table. Often, the acquirer will ask hundreds of questions about the target’s business plan, with a strong focus on scaling up operations or bottom-line profitability measures, while the target is much more interested in talking about top-line growth, new-customer acquisition cost, and churn rates. Management presentations and expert sessions often leave both sides wondering if they are headed for a difficult future. A frequent issue is when the acquiring company’s M&A team has a limited understanding of the tech firm’s technical architecture, hardware, or software and how it can be integrated with the industrial player’s products and services.

Acquirers that are not tech companies can advance the process by showing an early understanding of the target’s technology, business model, and success factors, which is especially important in a competitive auction situation. Buyers should not rely on price alone to carry the day; they need to win over the target’s management team with a compelling case for synergy and a vision for the combined operations. Open and candid discussions about potential culture clashes and how to solve them can help. Acquirers also have to clearly outline their cooperation and integration model for the target as part of the wider company—this is frequently a key concern for the technology firm’s management.

What do tech firms expect after the closing? Tech deals frequently founder because of misunderstanding over postmerger integration and how the target will operate once the deal closes. Target company management teams typically expect a high degree of continuing entrepreneurial freedom, which is what they are used to and which they (accurately) view as vital for top-talent acquisition and retention. These expectations often include maintaining the target’s standalone P&L and having the ability to financially motivate key decision makers in ways that do not fit into typical corporate compensation schemes.

Targets also look for their new parents to make decisions fast, often much faster than allowed by the lengthy decision-making processes that result from corporate policies and politics. Successful acquirers often establish separate governance procedures and mechanisms for their tech acquisitions.

Moreover, tech companies expect ready access to the acquirer’s product base and distribution network in order to achieve early, tangible win-win results. One big reason for failed technology acquisitions, in our experience, is when the acquirer treats the target’s technology as a pilot or as a fig leaf for the acquirer’s tech agenda, rather than as a means of strengthening its core business.

Targeted Processes for Tech M&A. While tech deals follow the same general processes as traditional transactions—target identification, transaction execution, and a decision about the right level of postmerger integration (PMI)—each phase presents its own wrinkles. Successful tech buyers make the following adjustments to their playbook:

- Expanded Resources for Identifying Targets. Internal M&A teams tend to specialize more in industry segments and technologies that are close to home. Sourcing tech targets requires wider search parameters and expertise. Successful companies augment existing teams with internal and external resources, including their own corporate venture capital departments and outside tech industry experts, to broaden the search for targets in emerging technologies and industry segments.

- More Agile Deal Execution. All aspects of executing a tech transaction require flexibility. For example, acquirers need to adjust to, and get comfortable with, shorter due diligence time frames (or risk being outbid by more fleet-footed competitors), different performance metrics (hit rates and customer churn rather than cash conversion or free cash flow), and generally less depth of information. Serial tech acquirers often borrow a tactic from the private equity sector. They augment their deal teams with senior advisors, such as former CEOs, from the target industry, who can give the entire deal team a head start by providing insights into the target company’s business environment and identifying key success factors for the team to focus on.

- PMI with a Lighter Touch. Reaping synergies in M&A typically involves full and close integration of the target. But experienced buyers of tech assets often opt not to integrate the acquisition at all. Instead, they manage it at arm’s length in order to avoid smothering innovative drive with corporate bureaucracy or undermining a successful, entrepreneurial culture. Many serial buyers set up incubators or accelerators for just this purpose. (See Corporate Venturing Shifts Gears, BCG Focus, April 2016.)

Organizing for Tech M&A. There is no one right way to organize the internal M&A function for tech transactions. We have seen several successful approaches taken by savvy clients, but these approaches do have some common components. For one thing, smart buyers are highly flexible with respect to where ideas come from and how transactions are handled: in the corporate center, in the business units, or even in separate organizations, such as corporate venture or innovation labs. Outcomes—identifying and executing good deals—are more important than organizational structures. Flexibility is also important for M&A team members; former traditional investment bankers are often matched up with entrepreneurs in residence. Because transactions involve different kinds of due diligence analyses and deal structures, these companies also make a point of including expertise from a wider range of expert functions (such as finance, HR, IT, and legal) earlier in the deal process and consistently throughout.

Experience counts in tech M&A as it does in all M&A, and so do flexibility, nimbleness, and a clear focus on specific M&A goals and outcomes and how tech acquisitions support corporate strategy. Smart buyers of tech assets tend to fine-tune all aspects of their corporate M&A machinery—aspects as varied as strategy, process, and the makeup of the team—to suit the agility required in tech deals.