Companies the world over are keenly aware that pricing can become a critical weapon in their arsenal. Companies also sense that to deploy pricing in a way that improves business outcomes, they must create a strategic pricing organization.

But how do they do that? Very often, the viewpoints around pricing strategy diverge—dramatically. There are those who think pricing must be efficient, while others believe it must be innovative. Some want it to support short-term goals, while others deem long-term ones more important. Many think pricing must meet external market expectations; others believe it must address internal margin pressures. And some perceive pricing as an operational task, while others think the responsibility must lie with the C-suite. The tensions around pricing can run high and deep.

Perhaps surprisingly, rather than bridging these gaps and providing much needed leadership on critical issues, a pricing organization created in this environment usually has little impact on pricing. Its roles and responsibilities are not well defined. It is unable to implement the critical processes and technologies that are required to make and track pricing decisions. And when the organization does issue guidance, it is often too late to influence business outcomes or out of touch with the marketplace and therefore ignored, fomenting more tension and further slowing the adoption of pricing initiatives. Despite the pricing organization’s efforts, a common complaint is still heard: “everybody touches pricing, but no one owns it.”

Companies can construct a strategic pricing organization amid internal differences, but they must focus on four fundamental building blocks: structure, decision rights and influence, skills and capabilities, and size. Companies that create a strategic pricing organization are bound to gain an edge over rivals. In fact, our studies show that companies’ profits are 1% to 2% higher when the pricing organization is regarded as a strategic partner than when it isn’t. (See “ Four Steps to Becoming Fluent in the Language of Pricing ,” BCG article, October 2015.)

Structure

Pricing is a team effort that requires constant cooperation and coordination among several functions, including sales, marketing, product management, and finance. That’s why companies must consider three factors when setting up the organization: the degree of centralization as well as the organization and reporting structures.

The Degree of Centralization. Companies must start by figuring out how centralized or decentralized the powers of their pricing organization should be. The degree of centralization should reflect the extent to which a company’s business units have the same customers and competitors and share internal capabilities and assets.

The more business units that serve the same customers, face the same rivals, and use common capabilities and assets, the more important it is to coordinate pricing decisions across units. Although centralization enables strategic accounts to negotiate favorable discounts and terms across business units, it also facilitates the sharing of valuable competitive intelligence among business units.

If a company’s customer bases are distinct, if it faces different competitors in different markets, and if it shares few capabilities and assets among its business units—as in the case of a conglomerate—the company will be best served by decentralizing the power of the pricing organization.

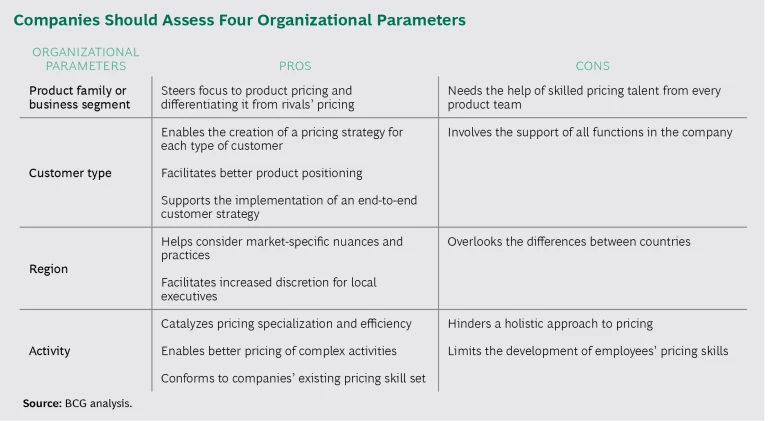

The Organization Structure. A pricing group can be organized by one or more parameters: product family or business segment, customer type (such as distributors or key accounts), region, or activity performed for customers (such as project management or lead generation). Companies should evaluate the pros and cons of using each parameter and strike a balance, which will improve the pricing groups’ effectiveness. (See the exhibit.)

How the pricing group is organized often reflects the maturity of the pricing function. A company usually starts with a simple structure. However, as the company’s appetite for more sophisticated pricing grows, and its ability to manage it increases, leaders generally adopt a matrix structure. For example, a leading Asian health care provider organized its pricing organization by payer type—individual, employer, or insurance company—and by region. That matrix helps the company set and manage pricing for its diverse channels and regional markets.

The pricing group is also often organized so as to correlate pricing to financial performance. A manufacturer of renewable-energy components structured the pricing function so that it began working closely with product development in the design stage. In addition, the company ensured that product management helped pricing managers understand the value added by each new product and how the product differed from its competition, that sales clarified the market dynamics, and that finance explained each product’s economics, the market and the aftermarket, and how to structure contracts to protect margins.

The Reporting Structure. In some companies, the pricing organization reports directly to the CEO; in others, it reports directly to sales or marketing or is embedded in the finance department. In all companies, the pricing organization should also have a dotted-line reporting relationship to a pricing council, which includes all functional heads with a stake in pricing decisions, such as the leaders of sales, marketing, product management, and finance.

A company’s direct reporting structure often reflects its industry, past reporting practices, the size of the sales force, and the number of regular pricing interventions that are necessary. There is no silver bullet; each structure has pros and cons.

Having the pricing organization report to the CEO elevates the pricing agenda and process to the top of the company, which in turn makes it easier to attract high-caliber pricing talent. However, this reporting structure creates a challenge: the CEO must find the time to consistently attend to pricing issues. The CEOs of small and midsize companies typically follow this practice.

A pricing organization that reports to sales or finance can make pricing decisions quickly, but they reflect each function’s perspective. Sales usually opts for volume-based pricing, whereas finance pays more attention to margins. Business-to-business companies and industrial giants usually have the pricing group report to sales; business-to-consumer and travel and tourism companies usually have pricing report to finance. When structuring reporting relationships, management should be careful to ensure that the pricing group doesn’t serve as a mere data center or guardrail for deals.

Unfortunately, companies often isolate the pricing organization, hurting their financial performance. The effect can be most severe when product life cycles are short and pricing and profitability are closely linked.

Regardless of the direct reporting structure, companies must acknowledge the need for pricing to be an intrinsic part of corporate governance, and the top management must recognize its role in pricing. The CEO or another senior leader should head the pricing council to ensure that it tackles critical pricing decisions, resolves conflicts (such as those between sales and finance), and acts as a steering committee. A pricing council typically meets monthly, but it should assemble at least quarterly.

Decision Rights and Influence

To create an effective pricing organization, top management must ensure that decision rights are clear. In addition, the organization must be credible and play an active role in everything related to pricing. Smart companies follow three simple rules:

- Encourage cross-functional inputs, but ensure a single point of accountability for all pricing decisions.

- Give decision-making authority to those who have pricing knowledge and experience. To react to a competitor’s price changes, for instance, a pricing expert must be able to gather competitive intelligence, develop impact scenarios, and craft a response plan.

- Have distinct responsibilities for the pricing council and the pricing organization, but ensure a close working relationship.

The degree to which the pricing organization influences pricing decisions usually reflects a company’s industry and past practices, the sales force size, and the number of regular pricing interventions required—the same four factors that generally affect the reporting structure. Pricing organizations seem to have more authority in companies that are in low-margin, low-growth industries, such as retail and commodities, as well as in companies that are in price-sensitive industries, such as travel and tourism.

Companies should monitor the balance of power between the pricing organization and the pricing council. If too much authority lies with the former, it can result in suboptimal pricing. If too much authority is given to the pricing council, it can result in a rigid system that paralyzes pricing decisions down the line. When companies bid on projects, for example, they often lose contracts or win contracts and incur losses (often referred to as the winner’s curse) because of hurried, last-minute pricing decisions made at the top.

In global companies with multiple brands and multiple lines of business, the pricing organization should consider sharing its responsibility with local leaders. For example, the pricing organization can provide guidance on pricing strategy and price setting and supervise compliance, and those on the frontlines can take care of execution. At a global water- and space-heating company that has a presence in more than 25 countries, the pricing strategy is developed at headquarters, and execution is left to local market leaders. This helps create a unified strategy, yet ensures flexibility in execution. Regional analysts report directly to their local market leader to ensure accountability, but they also have a dotted-line reporting relationship to the leader of the pricing organization to ensure that information and best practices are shared across markets.

The pricing organization in global companies should also consider sharing its authority with a specific function. For example, many business-to-business companies could boost revenues by empowering a sales force with a market-relevant target price and a limited amount of discretion to make decisions quickly if the final price is close to the target one.

Skills and Capabilities

A pricing organization requires people who possess hard and soft skills. Hard skills include the ability to gather and analyze data, estimate the value of products and services, and translate complex analytics into simple and actionable pricing guidelines for business units and functional teams. Soft skills include the ability to communicate clear and consistent instructions; develop, lead, and motivate teams; foster customer relationships even with senior leaders; and establish working relationships at all levels of an organization. Team members must also have knowledge of the company’s products, markets, and customers; the ability to develop pricing that reflects the business strategy; and the skills to identify and evaluate opportunities to change pricing. Recruiting people with these skills may require rethinking the hiring profile.

Many companies recruit pricing specialists who are data analysts and scientists, drawing candidates from pricing-centric industries (such as the airline industry), universities, and professional organizations. Although these recruits have the necessary analytical skills, they may not know how to influence and work with boundary partners. This is particularly relevant because pricing is a cross-functional activity. The ability to understand and influence sales, marketing, product management, and finance is imperative to the success of the pricing organization. It is also critical for those in this role to have good business judgment, because it is often the ability to tie the pricing strategy to the business strategy that determines the success of both. When a US-based industrial goods company set up a pricing organization, for example, it sought out members of the Professional Pricing Society. However, the company also recruited people from within; it realized that employees had the acumen and company knowledge and needed to be trained only in the use of pricing techniques and tools.

To ensure the success of a pricing organization, companies should put in place a recruitment schema for the group and career development plans for all members. Employees should know that working in the pricing organization can accelerate their career rather than be a dead end.

Size

Identifying the optimum size of the pricing organization can be vexing because it is influenced by multiple factors: the company size as measured by sales revenue; the size of the sales force; the number of customers; the number of business units, products, and stock keeping units; the number of channels and markets; the number of rivals; and the number of pricing interventions.

The type of industry also plays a key role in deciding the size. For instance, airline companies, which constantly change pricing as demand and supply fluctuate, need larger pricing organizations. Many airlines have about 50 people in pricing, whereas industrial companies of the same size are able to get by with far fewer.

BCG’s benchmarking studies indicate that pricing organizations have two to six full-time employees per $1 billion in company revenues. Small companies—those with revenues of $500 million or less—need pricing teams of at least five full-time people. After all, a minimum amount of analysis and cross-functional engagement is necessary in every organization.

As the size of a company increases, the number of people in the pricing organization should grow. Midsize companies, with revenues of $1 billion to $5 billion, often need 10 to 12 full-time employees; larger companies will need even more dedicated resources.

The size of the pricing organization will also increase as a company matures. In addition, the better a company gets at pricing, the more opportunities it tends to see for optimization. Some companies add people in hopes of spotting more opportunities, but that can become a vicious cycle—one that separates the best and the rest over time. The good thing is that a company’s return on investment in a pricing organization can be clearly measured, so wasting time and money is unlikely.

Building an effective pricing organization should be a priority for any company looking to expand its arsenal of competitive weapons. Critical to success, however, is creating an organization that is regarded as a strategic partner by all functional heads. Setting up the right organization structure, establishing the correct reporting relationships, and clarifying decision rights will give a pricing organization the support and credibility it needs to be effective.