Take a close look at the public education system in India, and the scope of the challenges is readily apparent. By the time they are ten years old, nearly 50% of children in government-run schools in India have fallen behind. As many as half the children in fifth grade do not even have the skills of a second grader: they can barely read and cannot do simple arithmetic. As a result, parents of more than 40% of children in India—a very large proportion of the population in a country where many families struggle simply to put food on the table—pay to send their children to private schools.

But if the problems plaguing the education system in India seem intractable, they are not. The state of Haryana, where 2.2 million children attend 15,000 government schools, has made progress—rapidly. In just two and a half years, Haryana has been able to arrest the decline in student achievement levels and generate improvement in all 15,000 public schools. This is a major accomplishment: all but one other state in India have seen learning levels remain static or decline. Certainly, educational achievement must improve much more, but the successes of Haryana’s School Education Department, working in partnership with The Boston Consulting Group, is clear evidence that large, complex government systems can undergo effective transformation.

In Haryana, success was the result of building a plan focused on four key steps. The department set precise and simple goals, identified the issues—both obvious and deeply rooted systemic problems—that had to be addressed, designed interventions that could work at scale within government financial and manpower budgets, and developed an implementation plan that was realistic and based on how people within the system operated and communicated.

The Challenge in Haryana

Haryana is a midsize state with a population of nearly 40 million. In addition to the 2.2 million students enrolled in government-run schools, there are roughly 2 million children who attend the state’s 5,000 private schools. It isn’t hard to understand why so many parents avoid the public school system. In 2013, Haryana ranked in the bottom half of all Indian states in terms of student achievement levels, and those levels were continuing to decline.

Attempts to address the daunting public school challenges in Haryana had come up woefully short. There have been projects and pilots in 50, 100, or even 500 schools in Haryana that generated impressive results. But like many other educational-reform efforts around the world, none of those projects could be scaled up successfully. That’s because most of them were led by NGOs, foundations, or entrepreneurs. In most of those cases, such organizations bring in their own people, money, and technology, and they produce great results. But when the time comes to roll out those projects across an entire school system, the education department lacks the resources to make it happen.

Delivering Real Change

The head of the School Education Department in Haryana understood the pitfalls of the bottom-up, pilot-led approach and was willing to take a dramatically different direction. Working with BCG, the department crafted a program aimed at raising the bar in Haryana. The effort was designed around four actions, which included setting a clear goal and applying strict discipline to ensure that all interventions were scalable within the state’s budgetary constraints.

Zeroing In on an Ambitious Goal and Tracking Progress. At the start of the Haryana transformation program, there was no dearth of ideas on how to fix the system. The proposals included changing the way teachers were recruited, sending principals on trips abroad to learn best practices, and installing computers in every school. All sounded promising, but it was difficult to determine which of them would generate the biggest payoff.

To bring focus to the effort, it was important to establish a clear goal. After much discussion and debate, the department set its goal: to ensure that by 2020, the knowledge and skills of 80% of the children in all Haryana schools would match their grade level.

To be sure, the establishment of that central goal sparked criticism. Some stakeholders, including teachers, insisted, for example, that the initiative should focus on ensuring that children learn the right life skills. Others contended that the department should focus on ensuring that it maximized the return on education expenditures. Clearly, arguments could be made in favor of these as well as other objectives. But having too many disparate goals could lead to a variety of uncoordinated projects and programs and dilute the impact of the overall effort. Setting one clear and ambitious goal brought discipline to the transformation initiative. Every potential element of the program was assessed to determine whether or not it would support reaching the 80% goal. Any that did not were off the table.

Just as important as setting the goal was measuring progress toward that objective. A new system was established to frequently evaluate all children from kindergarten through eighth grade. The assessments were not used to rate students individually. Instead, the aggregate data was analyzed to assess the school system’s overall performance and to determine whether the transformation was leading to the desired results.

Digging Deep to Unearth the Big Systemic Problems. Before a solution can be defined, it is important to determine whether the problem is properly understood. And in large government organizations many problems involve deeply entrenched, systemic practices.

Understanding the real root of a particular problem requires a willingness to challenge conventional wisdom. Consider a leading perceived problem in Haryana. We were told that large numbers of the teaching corps were lazy and unmotivated and that many never showed up for work. Furthermore, because it was extremely difficult to fire teachers, it was argued that this problem was impossible to solve.

But in digging into the issue, we could see that this wasn’t the case. There were, of course, some unmotivated teachers who often failed to show up for work. But they were a clear minority. The vast majority put in a fair day’s work. Their energies were, however, focused on concerns other than raising student performance.

Over the most recent two decades, India’s focus had been on building schools, enhancing infrastructure, and—by providing benefits such as midday meals and scholarships—incentivizing parents to enroll their children. With no clerical staff in schools, teachers were spending their time on everything from administration of scholarship programs to entering attendance data into the school’s IT system. In some small schools, teachers were even involved in directing construction projects.

At the same time, performance assessments focused on teachers’ execution of these tasks—not on how well they were developing their students. When, for example, senior officials visited schools, they asked about the quality of the infrastructure and whether children who qualified were receiving free meals. Academic performance and success were not even in the vocabulary. The systemic issue, it turns out, was not teachers’ laziness but rather how teachers were incentivized and evaluated.

We identified several such systemic issues, as well as more obvious challenges such as the need for better educational content and teacher training. With those challenges identified, we were able to design actions that addressed the most critical issues.

Imposing Discipline to Design Scalable Interventions. Looking for solutions, we observed a strict rule: every program had to be scalable. This meant that every initiative had to be executable within the current state budget and head count.

This rule engendered some creative solutions. Consider experiential learning. Many experts agree that teaching children through hands-on activities is more effective than teaching strictly from books. Ideally, the students should have beads, learning rods, and abacuses to help them learn math, but Haryana lacked the budget to supply these tools. When, however, a member of the team leading the overhaul observed a teacher using sticks and stones from a school garden as learning aides, we realized that experiential learning was possible without major investment. Teachers are now given information on ways students can use objects from their immediate environment as learning aids.

Similarly, for academically challenged students, we designed a remediation program that did not require additional resources. Many such programs require bringing in specialist teachers to work with children after school hours, but in Haryana, teachers were instructed to devote the first 90 minutes of each school day to working with children who trailed academically. No doubt the initiative did take some time away from children who were performing at grade level, but given the high numbers of children who were struggling, that was a reasonable tradeoff.

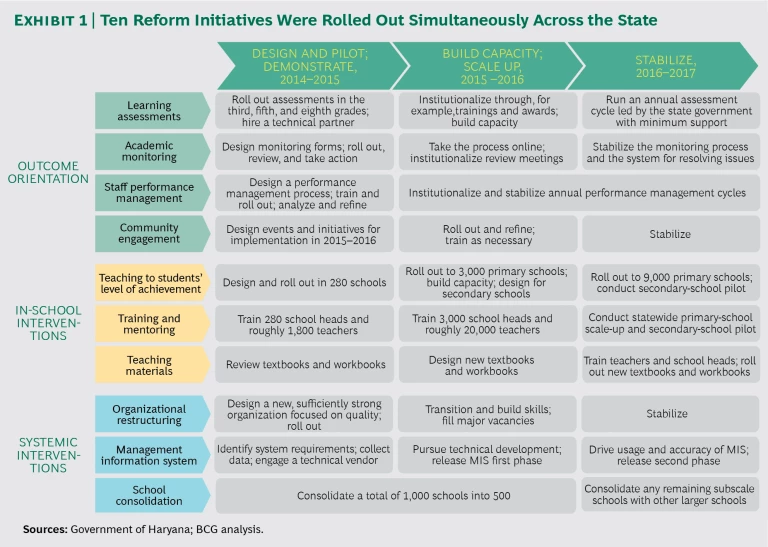

Ultimately, the team identified and quickly implemented ten scalable interventions. (See Exhibit 1.)

Using New Technology to Implement Innovative Initiatives. Understanding the change that was needed was one thing. Making it happen in Haryana was another thing entirely. Historically, the process for implementing a new program was simply to send a letter with the information to each of the 21 district offices. Those offices were then supposed to forward the information to the block-, or local-, level offices, which in turn were meant to send it to the individual schools. In many cases, the messages either never made it to the school level or were miscommunicated in some way.

To address the problem, the School Education Department harnessed new technologies to connect directly with teachers. Information on new initiatives is now sent to teachers using low-cost tools, such as Facebook, Google Docs, mass SMS text messaging, interactive voice response, and WhatsApp. Today, teachers use Google Docs to, for example, upload student attendance and learning-assessment information. WhatsApp, in particular, has become a powerful tool. The School Education Department has divided teachers into a few hundred WhatsApp groups, allowing important information to spread quickly and broadly. Teachers also use the app to question colleagues throughout the state about new initiatives and teaching strategies. Teachers from northeast Ambala district, for example, can ask questions about how to teach certain elements of the curriculum, and teachers from southwest Mahendragarh can respond in real time.

Haryana’s Stellar Gains

The impact of the reforms in Haryana has exceeded expectations. From 2012 through 2014, as the overhaul was being rolled out, the share of fifth graders who could do division increased 5% and the share who could read a standard second-grade text jumped 10%.

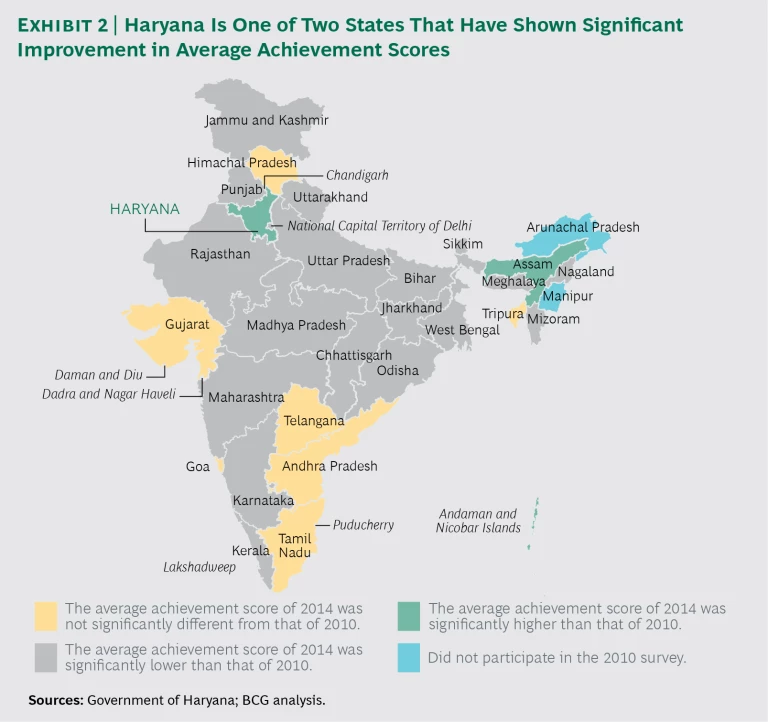

That was quite a reversal: from 2010 through 2012, the share of fifth graders who could do division had fallen 26%, and the share of children who could read a standard second-grade text had dropped 17%. According to the National Achievements Survey report published in January 2016, Haryana was one of just two states in India that showed improvement in learning outcomes across all subjects, with 28 of the 30 Indian states posting declines or no change. (See Exhibit 2.)

Today, in every school in Haryana, teachers have simple specialized materials and methods that help them deal with the complex heterogeneity in their classrooms. Once a week, mentors visit teachers to see whether they need any help. All students’ learning levels are assessed once a month, and the data is shared with the principals and teachers. When the supervisors of the schools visit, they focus on student learning records—not just data on buildings or enrollment.

Haryana’s education leaders are only at the beginning of their journey to remake public schools. But there is real momentum and indisputable progress. For a massive and complex government organization, that is something to be celebrated—and emulated.