China’s overall economic growth is slowing, but the Chinese consumer economy is still massive in absolute terms and poised for increasing growth. The country will see nearly $2 trillion in new consumption by 2021—about 27% of the total consumption growth that will occur in major economies during that time. China thus represents one of the biggest opportunities for consumer companies in the world for the foreseeable future.

To help multinational corporations understand this opportunity, we recently partnered with Alibaba to analyze the country’s potential consumer growth. (The project follows up on our previous research on the topic; see The New China Playbook: Young, Affluent, E-savvy Consumers Will Fuel Growth, BCG Focus, December 2015.) Our updated data and analyses confirm that many of the trends we identified in 2015 remain in play. For example, much of the new consumption growth will continue to come from upper-middle-class and affluent households, the younger generation, and e-commerce.

The large-scale trends reflect the broader driving forces behind consumption growth in China. However, identifying these trends is not enough. Companies need to drill down and look at more-granular information to understand how these trends affect the shopping habits and behaviors of Chinese consumers. To that end, we identified five emerging-consumer profiles that serve as examples of how rising incomes and greater digital access are leading to a far more heterogeneous consumer market. They illustrate in specific detail the ways in which large-scale trends affect specific consumer segments. A deep understanding of these segments will be critical as China’s consumer economy matures.

Consumption Continues to Grow

In our 2015 publication, we discussed how consumption in China was holding up despite macroeconomic forces that threatened to restrict it. That bears repeating. Despite some fluctuations from one quarter to another, China’s overall GDP continues to grow at less than 7% a year but consumption is increasing by more than 10% annually, largely because of structural shifts in the Chinese economy.

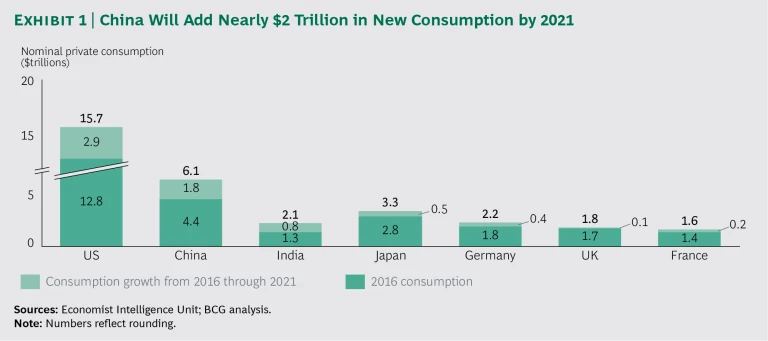

Even if GDP growth was to slow to 5.5%—a conservative projection—the country would still add a cumulative $1.8 trillion in new consumption by 2021, to reach $6.1 trillion. (See Exhibit 1.) China’s consumer market, both currently and as projected for 2021, is the world’s second largest, behind only the US. In fact, the projected growth in China through 2021 is equivalent to adding another consumer market the size of Germany’s.

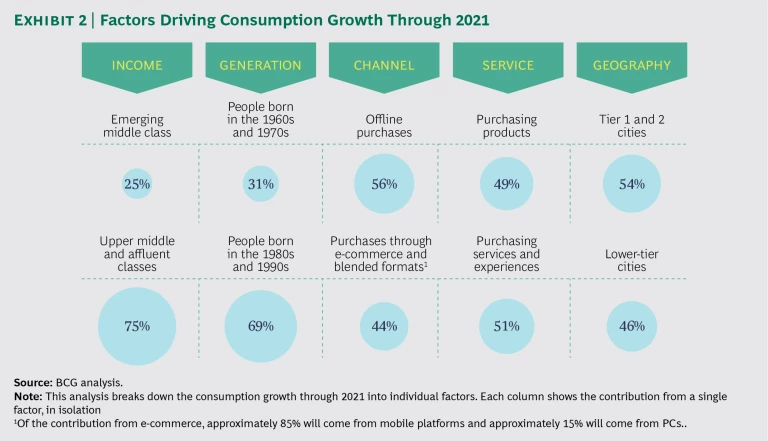

Three factors are the primary drivers of future consumer growth: China’s emerging upper-middle-class and affluent households, the spending habits of the younger generation, and the increasing role of omnichannel e-commerce. (See Exhibit 2.)

Growth in the Number of Upper-Middle-Class and Affluent Families

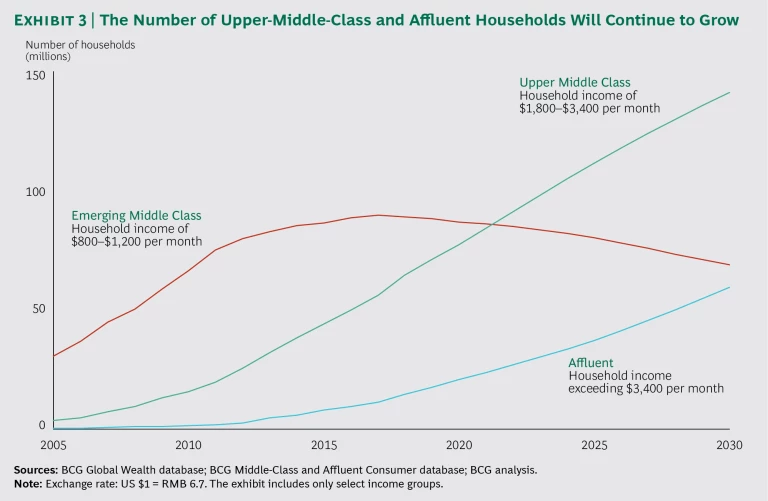

Income levels in China are rising, so the population of upper-middle-class and affluent families is rising as well. (See Exhibit 3.) These households have more accumulated wealth, and that leads to increased spending in discretionary categories such as furniture and home decoration, travel, and entertainment.

Moreover, consumers in these households are not just buying more, they are trading up: buying higher-quality products in certain categories, such as electronics, food, apparel, and children’s products. According to AliResearch’s “New Consumption Index” report, published in China in April 2017, consumption of midlevel to high-end products on Alibaba’s retail site reached $174 billion in 2016. In addition, AliResearch’s quality index showed an increase of 7.2 percentage points over the past five years, even as quantities declined.

The Purchasing Habits of the Younger Generation

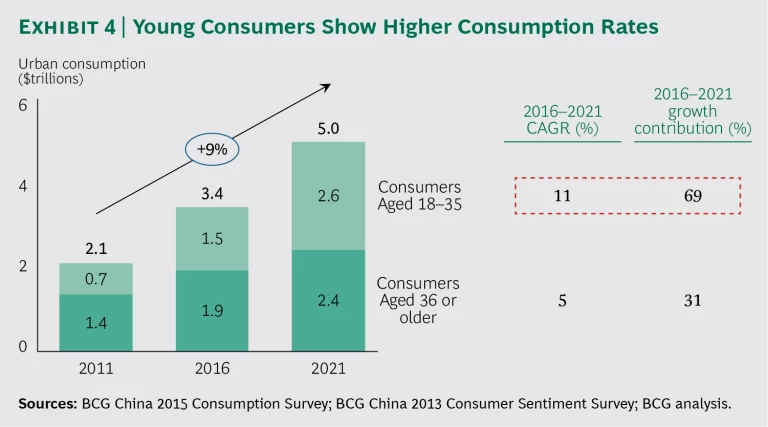

As in developed countries, the younger generation in China (people aged 18 to 35) shows a greater appetite for consumer goods. In 2016, this group made 1.5 trillion dollars’ worth of purchases (up from $700 billion in 2011), and projections call for a continued sharp rise in their spending, to $2.6 trillion in 2021, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 11%, compared with a CAGR of just 5% for purchases made by consumers aged 36 or older. (See Exhibit 4.) At that point, aggregate consumption by the younger generation will exceed that of older age groups in China.

At the same time, younger consumers in China are becoming more savvy and more demanding, with more specific and granular needs and wants. Consider a category like skin care. Previous generations in China needed just one or two products in this category. In contrast, 30% of today’s 18- to 35-year-old consumers buy five types of skin care products.

The Increasing Role of Omnichannel E-Commerce

The Chinese population is extremely connected via digital technology; the time people spend each day on smartphones, laptops, and tablets exceeds global averages. By 2021, more than 90% of purchases will involve at least one digital touch point (up from 70% in 2016) and possibly several. A transaction could begin when a consumer, perhaps prompted by a friend who texts a recommendation, conducts a web search to learn more about a product. The consumer might go on to check social media reviews about the product. Or a transaction could start when a consumer goes online to check prices and store hours. This highly fragmented consumer purchase pathway require companies to engage consumers at every one of the possible steps—with an integrated, digital experience—or risk losing them.

Other Growth Drivers

Two other megatrends are affecting consumption in China. Chinese consumers are increasingly buying services and experiences, rather than just products, and purchases are increasingly made not in tier 1 and tier 2 cities in China but in lower-tier cities.

Five Consumer Profiles

Although the three megatrends we’ve described are still the biggest drivers of China’s consumer economy on a macro level, knowing what they are is not sufficient to win the resulting revenue reward. Instead, companies need a microscopic view of the specific changes that result from the megatrends, changes in shopping behaviors and preferences among distinct consumer segments. As China’s consumer economy matures, its consumers are developing more diverse preferences for products and services. So, rather than looking at big, homogenous demographic segments, companies need a more precise breakdown of a much more complex Chinese consumer economy in which consumer segments are becoming more differentiated than ever before.

Distinct consumer segments have emerged as a result of the structural demographic and behavioral changes, and each segment has a unique set of needs. Companies that invest time to deeply understand these segments and trends will have a better chance of reaping the benefits of increased consumer spending in China. To that end, we have identified five specific profiles to illustrate China’s emerging consumer economy. This is not a comprehensive list; these five profiles are examples of how large structural changes are playing out at a microeconomic level.

The Savvy Shopper

Globalization, technology, and rising incomes have combined to create far savvier shoppers in China today than in the past.

Consider the apparel category. Two decades ago, consumers could buy these products only in person, and they were exposed only to brands available in stores in their home city (or in places consumers traveled to). Today, virtually all major global brands are available in China and have built up a significant presence in major shopping malls, online channels, or both. As a result, consumption is not limited to certain segments of the population. Instead, everyone in China is a potential consumer, and people are far more discerning in evaluating products than they were in the past. They are more brand-aware than consumers in other parts of the world. They know what is out there, and they are able to “shop the world.”

Moreover, the availability of a greater number of products—with a wider variety of features, price points, design attributes, and other aspects—launches a kind of virtuous loop. Consumers are exposed to more, through digital channels, friends, and increased brand penetration. They are better equipped to research products and find exactly what they want. Companies race to give them more. And the cycle repeats.

Significantly, consumption boundaries—typically defined by age and gender—are less relevant to consumers today. Rather than being confined by tradition and social mores, people are growing more independent in the products they choose to purchase. Male grooming habits are a good example. Researchers have shown that men now devote more time and attention to personal grooming than before. Men living in tier 1 cities in China now spend 24 minutes each day on grooming (up significantly in the past decade), and 88% of them access grooming and fashion information online. Not surprisingly, spending on skin care products among men is growing: from 2014 to 2015, men’s spending on these products increased by 24%, compared with just 11% growth in overall skin care product spending.

Similarly, the idea of retirement is changing in China. For example, older generations in the country are far more likely to spend money on travel, and to travel to more-distant destinations. From 2012 through 2015, spending on travel among this population grew nearly 22%, according to the China National Tourism Administration, compared with overall growth in travel spending of 16.8%. Older generations are also more likely to spend money on sporting activities that were once reserved for young people, such as running and yoga. (One of Reebok’s celebrity spokesmen in China is Wang Deshun, an 80-year-old actor and artist who recently walked the runway in a fashion show.)

The Single Person

Demographic shifts are creating a growing number of single people in China. Among urban populations, 16% now live alone, compared with just 5% ten years ago. Many people are choosing not to marry; nearly half say they are indifferent about whether they marry. As a result, 21% of those older than 35 are single (up from just 4% a decade ago).

There are various reasons for this shift. Some people are more career-oriented than in the past, and social media networks make it easier for people living alone to stay connected. The trend is accompanied by a profound change in people’s perceptions of remaining single: the concept is no longer stigmatized in the Chinese culture, where getting married and starting a family is considered a filial duty. As a result, single individuals now have a different lifestyle—people are more likely to live, dine, travel, and pursue activities by themselves—which leads to changes in the products they purchase.

In general, single people seek smaller volumes, greater convenience, and higher-quality goods. For example, sales of small appliances—such as minifreezers—are rising in China. At the grocery store, foods are increasingly available in smaller pack sizes and in prepared forms—such as vegetables that are prewashed and prechopped—that make cooking more convenient. Even grocery store design has changed, with smaller and more upscale markets that carry a wide selection of imported products becoming popular.

The Ecoconscious Consumer

Over the past decade, the awareness of environmental factors and sustainability has risen dramatically in China. This concept spans both the personal level (“I want my purchases to be good for me”) and the planetary level (“I want my purchases to be good for the planet”).

A recent survey by GfK found that 80% of Chinese consumers feel that brands and companies should be environmentally responsible. A separate study of Alibaba’s customers—conducted by AliResearch—found that 66 million (or 16.2%) bought five or more “green” products in 2015, up from just 4 million in 2011 (3.4%). Notably, they are willing to pay a price premium—up to 33%—for those products.

These consumers want healthy and organic food, apparel made from natural products (such as cotton and linen), energy-saving electronics, and natural skin care products. They are also more willing to support environmentally friendly companies—for example, those that reduce their packaging, encourage recycling, and take other steps to mitigate their environmental footprint.

The Passionate Trend Seeker

Chinese consumers are passionately taking up new interests, and they are increasingly willing to spend money on those wide-ranging interests—not only on products but also on experiences that will enrich their lives. In the past, many Chinese people focused more on working and professional advancement, and they had simple hobbies that did not require high levels of spending. Globalization, technology (which gives people greater exposure to the world), and rising income levels (which give them the time and money to follow their interests) are the driving forces behind this trend.

Travel is a major focus of the passionate trend seeker. In 2015, more than half of Chinese travelers visited Japan and Korea. Over the next three years, Chinese travelers will broaden their horizons; the Huron China Luxury Travel report indicates that they are increasingly interested in visiting places like Africa, the Middle East, and even the North and South poles. Extreme sports such as rock climbing, car racing, and surfing are all projected to grow rapidly in the next several years.

The Connected Consumer

Chinese consumers are fully digitized and connected. The numbers alone are remarkable. Quest Mobile researchers estimate that China has 927 million active mobile internet users, along with 707 million users of WeChat (a messaging and calling app), 272 million users of Alipay (a mobile payment service), and 231 million users of KuGou (a streaming music service).

E-commerce is more attractive in China than in other markets, in part because of the nation’s strong digital infrastructure. Notably, Chinese consumers say they buy products online more for convenience than price. Yet it also means the country is ripe for smart devices and services that use mobile technology to increase their functionality. Consumers in China are also particularly open-minded about the early adoption of new products and technologies. Smart home appliances are a good example: whereas consumers in developed markets tend to look for complete system solutions, consumers in China are willing to purchase one smart appliance at a time.

In addition, digitization is changing consumers’ lifestyles and product needs and desires. For example, digital entertainment means that people are likely to socialize with friends at home rather than go out. Similarly, digitization means that certain types of content—such as anime and comics—are more easily accessible, leading to the rise of anime culture among younger people in China. In both cases, these lifestyle changes trigger corresponding changes in the products that these consumers buy.

Implications for Consumer Companies

To capitalize on the emerging consumer opportunity in China, companies should keep several priorities in mind.

Consumer Segmentation

In the past, it was sufficient for companies in China to apply a relatively basic consumer segmentation scheme built primarily around demographic factors such as age, gender, and income. The needs and desires of consumers in each group were more or less homogenous and predictable. Today, the number of consumer segments is growing, and they are far more differentiated and distinct. Consumer companies need to keep up with this shift.

To put it bluntly, if you have not identified more segments in China than you had pinpointed a year or so ago, you’re almost certainly behind. In addition, because the market is changing so rapidly, you will need to update your segments at least every 12 to 24 months. But segmenting along consumer dimensions alone is not enough. To understand the factors that lead to a purchase, companies need to know the context of that purchase (such as the time of day, the consumer’s mood, and who he or she is shopping with).

Brand Structure and Strategy

As consumer segmentation becomes more precise, brand structure and strategy need to follow suit. Rather than offering a small number of products that are merely acceptable to most segments, you need to understand the increasingly diverse preferences of emerging consumer groups and subsegments and review your brand structure and strategy to gauge how well your products meet those needs.

Consumer Engagement

A decade ago, Chinese consumers evaluated products primarily based on their functional and technical elements: Does this do what I need it to do?

Today, the emotional connection to a brand or product is equally important. That emotional attachment will ultimately build brand loyalty. For consumer companies, this points to a clear imperative: evolve the ways in which you engage with consumers, not only regarding product attributes—for example, design features—but also at every touch point along the way. Every interaction is an opportunity to increase the emotional connection—or to undercut it. You need to understand how your products and services meet specific consumer needs, and those needs are increasingly functional and emotional, rather than just technical.

Value to Consumers

In addition to forming an emotional attachment, Chinese consumers are intensely focused on the value of products and services. They require that companies justify their prices. Having a well-known brand is no longer enough to win over consumers.

Channel Design

As e-commerce becomes more prevalent, consumer companies must create a format that seamlessly integrates online and offline elements. At every step of the purchasing pathway, you need to design meaningful touch points that deepen your engagement with consumers, give you critical data and insights about their wants and needs, and help you win them over as brand loyalists who will advocate for you among their friends and family.

China’s economy is changing rapidly, yet the underlying story is one of strong growth in consumption through 2021, at least. Companies that build a detailed understanding of the trends that are driving this consumption growth and how those trends are driving new shopping behaviors, preferences, and habits will be front-runners in a market worth trillions of dollars.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following people for their assistance with this publication: Yun Wang, an advanced researcher and unit head at the Institute of Economic Research in the National Development and Reform Commission; Qing Wang, a senior research follow and deputy director-general at the Institute of Market Economy in the Development Research Center of the State Council; Chris Tung, the chief marketing officer at Alibaba Group; Bo Liu, the executive director at Tmall; Liana Zheng, an executive specialist at Tmall; Su Diao, a senior specialist at Tmall; Jacob Yan; a specialist at Tmall; Jacob Yan, a specialist at Tmall; Echo Si, a specialist at Tmall; Roddick Wu, a senior planner at Tmall; Seven Zhang, a specialist at the business intelligence department at Tmall; Gigi Guan, a senior analyst at the business intelligence department at Tmall; Hongjie Wan, a data mining engineer at AliResearch; Zhoupei Xie, an executive specialist at AliResearch; and Yonghua Pan, a senior specialist at AliResearch.