Despite recent political and economic turmoil, Thailand continues to be a consumer force to be reckoned with. The country’s overall growth is slow compared with that of rapidly developing economies, such as India and Vietnam. But we’ve identified pockets of strong growth in certain consumer categories, and e-commerce is increasing swiftly. What’s more, Thaland’s rising incomes are generating optimism about the future among its people and are increasing consumer demand for a wide variety of products. (See the sidebar.) This is good news for companies hoping to make further inroads in the region. But where will investments in Thailand deliver the biggest payback?

Thailand’s Upward Trajectory

Over the past 40 years, Thailand’s economy has generally been healthy and growing, except for a period from 2013 through 2015, when political turmoil and a slowdown in global demand hurt Thailand’s exports and reduced the value of the country’s currency. Despite the temporary slowdown, Thai consumers are among the world’s most optimistic—largely because of their increasing standard of living. Thailand is a middle-income country, which the World Bank defines as a per capita annual income of between $1,026 and $12,475. Thailand falls at the upper end of that scale. More than half its citizens are members of the MAC population, defined as making over 10,000 baht ($100) per month.

By 2030, the MAC population is expected to be higher in Thailand than it is in Malaysia today, and Thailand’s affluent class is growing even faster than the middle class. This steady increase in income is driving consumer demand and purchasing, presenting an opportunity for companies that offer consumer products, trade-up options, luxury goods, and experiences. Companies that can intensify and capitalize on their brand strength will be well positioned to increase their market share among these affluent consumers.

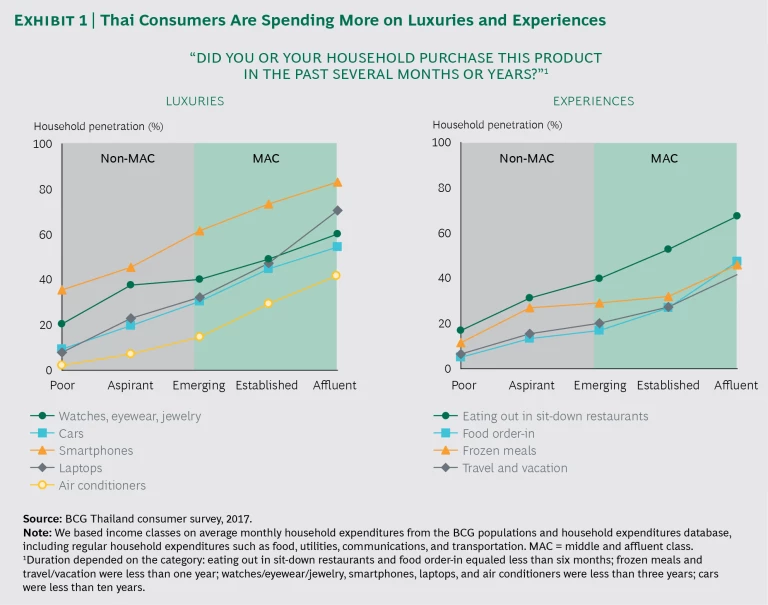

To answer this question and gain greater insight into consumer trends and behaviors, BCG’s Center for Customer Insight surveyed 4,000 Thai people aged 20 or older in all income classes and evenly split between men and women. We segmented Thai consumers into five basic income brackets: poor, which refers to households subsisting on income of less than THB 10,000 a month; aspirant, THB 10,000 to THB 15,000; emerging, THB 15,000 to THB 30,000; established, THB 30,000 to THB 50,000; and affluent, more than THB 50,000 a month. For the purposes of this study, we regard the last three income segments—emerging, established, and affluent—as constituting Thailand’s middle- and affluent-class (MAC) population.

All respondents indicated that they either directly make household purchase decisions or influence those decisions. We analyzed their purchase and spending patterns in 51 product categories, from appliances and clothing to alcohol and snack foods. To deepen our understanding of Thai consumers, we conducted a series of focus groups to explore online behaviors, e-commerce, places where people shop on- and offline, and the evolving role of women in purchase decisions.

Our analysis of the survey data and the focus group input reveals five major trends that are shaping Thailand’s consumer landscape:

- Growth is strong in categories that offer indulgences and experiences.

- Brands matter, and consumers are very brand loyal.

- Women have substantial buying power, even in traditionally nonfemale categories.

- A new social media model is driving e-commerce.

- Convenience stores are shaping shopper behavior.

These trends—and their strategic implications—provide critical input for companies seeking to expand their reach and share of wallet in Thailand’s consumer markets. Let’s look at each trend more closely.

Growth Is Strong in Indulgence and Experience Categories

Our analysis shows pockets of strong growth in several product categories, reflecting Thailand’s rising affluence. For instance, small indulgences such as ice cream, cakes, chocolates, fresh milk, juices, bottled water, and crispy snacks increased their penetration of MAC and non-MAC households by 10% to 15% from 2013 through 2016. During the same period, some categories—such as frozen meals—grew even more, as much as doubling among some consumers, especially those in MAC households.

As incomes increase, however, Thai consumers—particularly upper-income shoppers—are spending even more on experiences such as dining out and leisure travel as well as on luxury products such as watches, jewelry, and smartphones. (See Exhibit 1.) For instance, only 31% of aspirant-class consumers dine out, compared with 68% of the affluent class, and affluent consumers spend nearly 300% more when they do. Thailand’s consumer patterns are similar to what we’ve seen in other countries as household incomes rise. Once consumers can meet their basic needs, demand for small indulgences increases first. Then, when earnings reach middle-income levels, luxury products and services become more popular—and experiences gain momentum.

Compared with other consumers in Southeast Asian countries, Thai people are more likely to spend and indulge, as reflected in their higher debt levels. The consumers we spoke to felt they deserve these indulgences because of their hectic lifestyles and tendency to work hard. By contrast, the typical Southeast Asian consumer is more inclined to save and invest.

Brands Matter, and Consumers Are Loyal

Although most consumers in Southeast Asia are very price conscious and will switch brands for better discounts or promotions, Thai consumers are willing to pay more for many of their favorite brands. In fact, our analysis indicates that people in Thailand are the most brand-conscious and brand-loyal consumers in the region. And they’re loyal to brands in a variety of categories, from soaps and cosmetics to foods, beer, and snacks. Of the consumers we surveyed, 75% agreed with the statement “I look for my favorite brand and purchase that,” compared with 39% in the Philippines and 40% in Vietnam. Companies that recognize this characteristic of the Thai consumer can build and leverage brand equity to create strong consumer pull and loyalty. But at the same time, a company’s brands must rank number one or two in a category in order to achieve strong loyalty among consumers.

Women Have Substantial Buying Power

By regional standards, Thai women are well educated, well paid, and digitally savvy. Thai women aged 15 or older have one of the highest employment rates (64%) of women in any global economy, including those in Asia, North America, and Western Europe. Their disposable income relative to Thai men’s is also higher than in other developed Asian economies. In 2015, 8.8 million Thai women had at least a high school education, compared with 8 million men.

Today’s Thai women are confident, liberated, and independent—and they feel secure when earning their own salaries. “Women are now equal to men,” an HR manager and mother said. “Earlier, it was not so. Today, women are more qualified, stronger, and confident. They have dual responsibilities, earning income for the household and raising a family.” Explained another woman, “Society is changing so fast because of exposure to social media, technology, education of women, the need for money, etc. So family dynamics and expectations of women also had to change.”

For these reasons, female shoppers in Thailand, especially those women who work, are more likely to be the primary decision makers for household purchases, compared with women in other Southeast Asian nations, even for products such as alcohol and durables, which have not traditionally been viewed as women’s categories. Women in general and single women in particular make purchase decisions across a variety of product categories, from items such as makeup and groceries to chocolate, tablet computers, and durables such as washing machines, refrigerators, and microwaves—a trend that only increased from 2013 through 2016. Interestingly, Thai women are also more likely than men to do research online (27% versus 21%) and buy products online (29% versus 18%). Shopping is a popular activity, a reward for working hard. Many consumers love the convenience of shopping online using laptops or mobile phones and like avoiding the traffic they encounter when shopping offline.

Thailand’s changing demographics also contribute to the increasing power of female shoppers. Families are becoming smaller, and birth rates are dropping. Nuclear families averaging three people are the norm today, and Thailand’s low birth rate puts it on a par with countries in the developed world. According to a recent consumer survey from BCG, Thailand also has more single women than other countries in Southeast Asia: 31%, com-pared with 26% in Indonesia and 23% in Vietnam.

New Social Media Model Drives E-Commerce

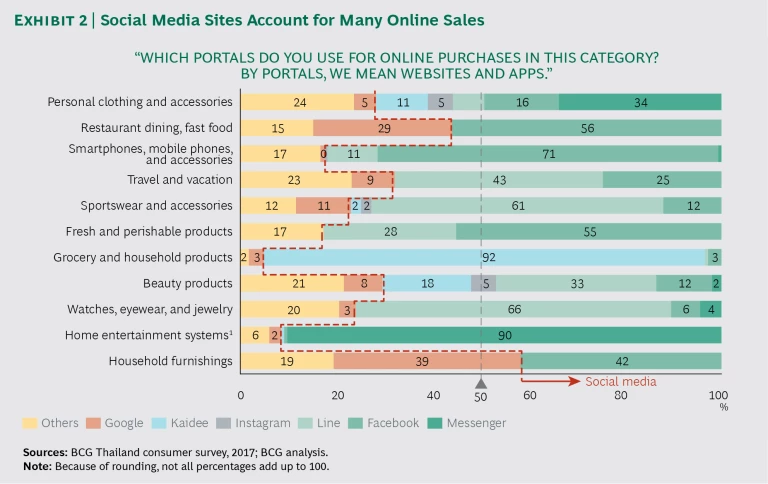

E-commerce in Thailand is growing at double-digit rates, as a result of the increasing use of the internet, smartphones, and credit cards. About 40% of purchases by Thai consumers are digitally influenced, and consumers reported conducting 50% to 60% of their online research for a wide variety of products on websites and apps such as Messenger, Instagram, Line, Kaidee, and Facebook. Thai consumers are comfortable buying most things online, except for jewelry, medicines, and perishable grocery items. And like elsewhere in Asia, Thailand has developed a social media model of online sales, where consumers sell to one another. Social media commerce accounts for more than 40% of online sales in categories such as phones and accessories, cosmetics, and clothing. (See Exhibit 2.)

Thai online shoppers are savvy. They understand the difference between high-risk social media sellers and established online marketplaces such as Lazada and Alibaba. Most Thai consumers discover social media shopping opportunities through ads on Facebook, Instagram, and other social media sites. A sales supervisor in one of our focus groups typifies the social media shopper. He joined a group of local camera enthusiasts on Facebook and bought a second-hand camera lens on the site from a seller who had received good reviews from his online friends. A housewife we spoke to shops on Facebook through online display ads and searches for products on sellers’ websites, but she keeps an eye out for scammers. “I know the sellers sometimes cheat,” she explained, “so I order mostly low-value items such as phone accessories, cosmetics, makeup, and party costumes.”

The social media model makes online buying in Thailand a treasure hunt and an adventure. Shoppers look for bargains on their favorite brands and negotiate with small businesses and individuals, hoping to land a great deal—and often succeeding. “I like that I’m able to talk to sellers and negotiate with them,” said one Thai shopper. Online shopping on social media is much like visiting a Thai market in the offline world, where colorful chaos reigns, bargaining is expected, and a limited-edition product or amazing buy is just around the corner.

Online buying isn’t just an urban phenomenon; urban (27.2%), suburban (21.6%), and rural (20.8%) consumers alike shop online because it makes a wide variety of products available to consumers with limited access to stores. In rural areas, small and midsize businesses also buy online because of the convenience. Still, retailers in Thailand need an omnichannel strategy because many shoppers research and buy

offline as well as online.

Compared with their regional peers, Thai consumers are digitally sophisticated. They know how to evaluate online and offline deals, understand payment and delivery methods, and recognize the differences among online platforms. Of the consumers who are digitally connected and go online, 95% have smartphones. Thai consumers also spend more time online—three hours per day on average, compared with two hours per day spent by their regional peers. Consumers aged 20 to 39 make the most online purchases.

Convenience Stores Are Shaping Shopper Behavior

Driven by demand and an increasing number of outlets, convenience stores are the fastest-growing channel in Thailand. Consumers who shop in these stores tend to buy fewer items more frequently—and often more spontaneously—rather than doing a major weekly shopping trip for the household. Moreover, the line between grocery shopping and convenience shopping is blurring.

In part, this is a result of changing lifestyles. A middle-class 35-year-old consumer explained why he shops at a nearby convenience store: “My job is very demanding. I’m not usually home until 10 p.m., and on weekends I want to spend time with my kids, not drive a long way to hypermarkets and stand in queues.” Although the 7-Eleven carries almost everything that he needs, he wishes it sold goods in larger sizes. A Thai woman who stays at home with her children started shopping at 7-Eleven after she had kids, explaining, “I don’t know how to drive, and I’d have to take a taxi to the hypermarket. Now I just buy whatever I need from 7-Eleven. It’s open 24 hours.”

From 2011 through 2016, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of traditional mom-and-pop grocery stores was essentially flat at just 2%, and their share of total sales volume decreased from 59% to 54%. By contrast, convenience stores reported a CAGR of 10% during the same period, and their share of total sales volume increased from 14% to 19%—a trend we expect will continue on the basis of our survey results. Thai consumers said they plan to increase their spending at convenience stores at the expense of hyper- and supermarkets.

Convenience stores have a more limited assortment of merchandise than supermarkets, but consumers perceive that these shops offer better service and greater convenience. In addition to selling cigarettes, liquor, grocery items, and sundries, convenience stores in Thailand offer fresh meals—including seafood, meat, and chicken—for singles, empty nesters, and smaller families. As in Taiwan and Japan, convenience stores are particularly popular among Thailand’s rapidly aging demographic.

Of the competing convenience store chains, Big C and Tesco scored highest with consumers on variety, while 7-Eleven received the top marks for convenience and service. Regional retailers such as 7-Eleven (operated by Charoen Pokphand Foods in Thailand), FamilyMart, and Lawson have ambitious growth plans. According to Bangkok Post, 7-Eleven will allocate 60% of its planned capital expenditure (9.5 billion baht to 10 billion baht) this year for store expansion and renovation. It was already present in more than 10,000 stores by the end of June 2017.

Looking Ahead

Companies aiming to expand their reach in Thailand must understand how consumer preferences and behaviors are changing as incomes rise, women gain more buying power, and social media e-commerce rapidly expands.

Using these insights on Thai consumers as a starting point, forward-looking companies can develop an effective strategy for making further inroads into the country’s most promising markets. Key questions to ask include:

- What affordable luxury products or differentiated experiences can we offer the growing affluent class?

- How can we upgrade our brand image, strengthen our brand equity, and extend that equity to new or adjacent offerings, especially as consumers move from the middle class to the affluent class?

- How can we target women and their unique needs?

- Do we need to rethink our channel strategy in light of the growing importance of e-commerce and the trend toward convenience stores?

- How can we avoid channel conflict?

The answers to these central questions will point the way to the right branding, packaging, pricing, marketing, and distribution decisions—and a competitive edge as Thailand’s consumer markets continue to grow.