Medical technology is poised to become one of the next industries to break out of emerging markets and play on the global stage. Such names as Mindray Medical International and BGI, both from China, and Transasia Bio-Medicals of India could become as recognizable in industry circles as Lenovo and Huawei.

Compared with other industries, medtech has been a late bloomer in emerging markets. Of the revenues generated by the top 200 medtech companies globally in 2015, emerging-market companies contributed just 2%.

Multinationals currently hold a strong position in emerging markets. Many of their products and services have solid intellectual property protection and already meet various government standards and regulations. The multinationals also have long-standing relationships with the large hospital and health care organizations in emerging markets. In addition, many of them straddle several segments of the fragmented medtech industry, such as equipment, devices, tools, and supplies, which has helped them achieve a scale in these markets that eludes more narrowly focused companies.

But the multinationals’ advantage could change quickly. Demand for health care is growing rapidly in emerging markets, a function of rising household incomes, increased discretionary spending, and aging populations. Governments are also investing heavily in health care to combat chronic and critical illnesses.

This rising demand gives local companies a chance to make inroads. Local medtech companies understand these markets and know how to adapt products and business models to the needs of customers. They are also increasing their R&D spending and expanding their footprint through M&A.

Ready to Take Off

Given its small size within emerging markets, the medtech industry is easy to overlook. Of BCG’s 100 global challengers—fast-growing, fast-globalizing emerging-market companies—Mindray, China’s largest medical equipment supplier, is the only medtech representative.

There is also only one medtech company, Wego, on BCG’s list of 1,500 global champions—a broader group of fast-growing companies from emerging markets. Many up-and-coming companies simply did not make the $500 million revenue cutoff.

Overlooked industries have a way of making a surprisingly big splash in emerging markets, and the emerging-market medtech companies certainly have the potential to grow rapidly from a small base. Among the top 100 global pharmaceutical companies, revenues of those from emerging markets rose from $4.5 billion to $119 billion from 2005 through 2015. Emerging-market companies in other industries, such as telecommunications, construction and engineering, and airlines, have followed similar though less dramatic trajectories.

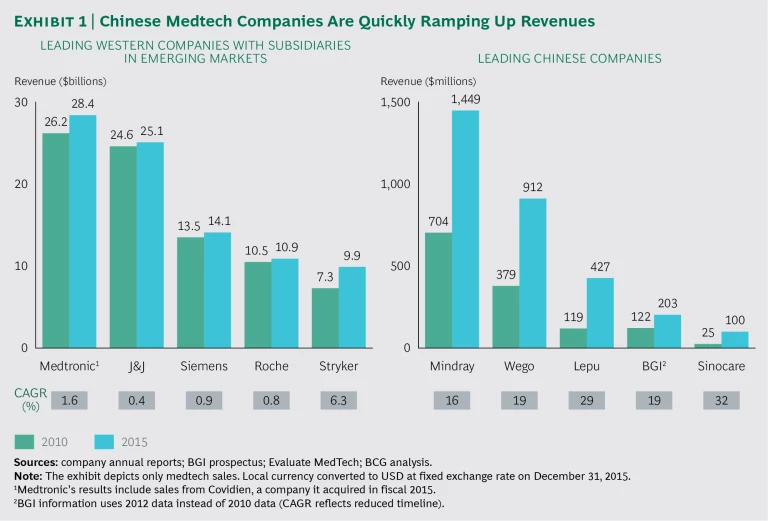

The emerging-market medtech industry is showing signs that it, too, is on the early, steep slope of the S curve. Chinese medtech companies, for example, are growing much faster than their Western peers. (See Exhibit 1.)

With the rising tide of health care spending and the development of health care infrastructure in emerging markets, this growth should continue. It could even accelerate if emerging-market medtech companies establish global aspirations and build the capabilities, including M&A expertise, to expand overseas.

The Rise of Emerging Markets

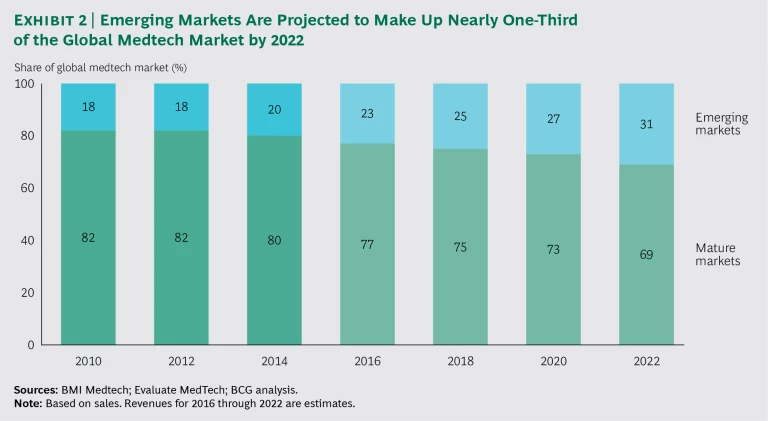

Emerging markets currently account for less than one-quarter of the medtech industry’s global revenues, but their share is likely to reach nearly one-third by 2022. (See Exhibit 2.) The medtech market in China, already the second largest in the world, is projected to grow by about 13% annually from 2015 through 2022. India’s medtech market, currently the fifth largest, could rival Japan’s and Germany’s in size by around 2022 if it continues its 17% annual growth.

Within narrow segments of the industry, emerging-market companies are already dominant. In the China market, three local companies—Biosensors International, Lepu Medical, and MicroPort—currently sell 80% of all drug-eluting stents. As recently as 2004, multinationals had a volume market share of nearly 90%. The market for direct radiography—a digital x-ray method—has also flipped in China. Local companies have taken one-half of the volume from multinationals, which had a 100% market share in 2004. In India, Transasia has become the number one supplier of in vitro diagnostic (IVD) equipment and reagents, and the company continues to spread its low-cost model to other emerging markets and even mature markets, such as Germany and the US. (About one-half of revenues originate outside of India.)

To date, local medtech companies in China have had the most success in segments that pose lower technological barriers. For example, they have grabbed 10% or less of the device market, as measured by value, in the technologically intensive fields of endoscopy and minimally invasive surgery but half or more of the market in patient monitoring and orthopedics.

As their technological skills sharpen, medtech companies in emerging markets are likely to succeed not only in their current businesses but also in new ones. Compared with multinationals, emerging-market companies have four built-in advantages: lower costs, localized products, innovative go-to-market approaches, and government support. Although these advantages are shrinking, they continue to serve as platforms for growth.

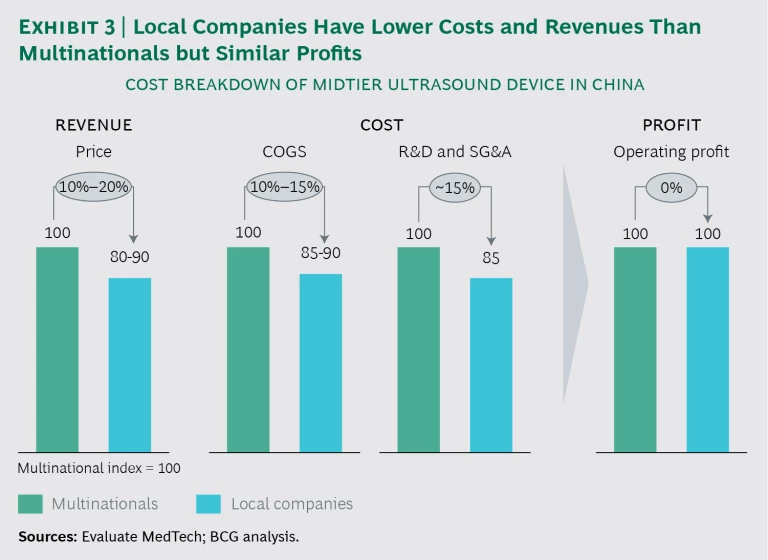

Lower Costs. Emerging-market medtech companies still have lower costs than their Western competitors. (See Exhibit 3.) Mindray, for example, can sell a midtier ultrasound product in China at a discount to multinational competitors while maintaining profitability and a positive customer experience, and devoting 10% of revenues to R&D.

This advantage will likely persist even as multinationals build manufacturing and R&D operations in emerging markets. For many products, local companies spend less on nonessential elements than do multinationals, which are often intent on maintaining their branding edge. For example, MRI machines built by emerging-market medtech companies are often less visually appealing because they use less expensive material and offer fewer costly bells and whistles, but their functionality is good enough for most medical practitioners.

Because lower- to midtier products are less costly to engineer, the R&D operations of emerging-market medtech companies are also less costly than those of their multinational competitors. This advantage, however, may diminish for sophisticated products developed by more expensive talent.

Localized Products. Emerging-market companies are often more successful than multinationals at tailoring their products to local needs and constraints. China’s Mindray has a presence in nearly three-quarters of all medical organizations in India. The company conducted deep customer research in India, established local operations, hired local employees, and tailored its line of patient monitoring, ultrasound, and IVD equipment to address local unmet needs. For example, it recruited local engineers and operators to provide 24/7 customer service and built a local marketing and sales team.

Emerging-market medtech companies have also found a less expensive alternative to negative-pressure wound therapy, which in mature markets is a popular way to promote the healing of acute and chronic wounds. The traditional pump- and vacuum-based therapy sold by Acelity and Smith & Nephew requires special equipment, which can cost more than $10,000 a unit, and a dressing that costs nearly $900, yet the procedures are not covered by most public medical insurance in China.

WuHan VSD Medical Science & Technology has created an approach that makes use of the wall-suction equipment common in large hospitals in China. Hospitals need not buy the expensive pumps, medical practitioners need not carry special equipment on their rounds, and patients pay lower out-of-pocket expenses thanks to a Chinese dressing that costs about $400 less. (In response, multinationals are adjusting their product portfolios.)

Innovative Go-to-Market Approaches. Emerging-market medtech companies have found alternative routes to reach patients when multinationals have tied up traditional channels.

In India, Transasia has taken advantage of channel segmentation to become the number one IVD provider. In large metropolitan areas, the company has invested in an in-house sales force of about 400 and a service force of about 200. These reps cover more than 30,000 labs. To achieve even broader coverage, Transasia has a network of 350 non-exclusive dealers that sell small-ticket items, generate leads, and work with a group of subdealers. Transasia can afford this channel strategy because it has lower manufacturing costs than its multinational competitors, such as Abbott and Siemens.

Government Support. In many emerging markets, local medtech companies benefit from direct and indirect government support along the entire value chain. Governments often subsidize R&D, speed regulatory approvals, provide tax and financial support, encourage domestic sourcing, and provide favorable reimbursements for local companies.

Wego’s orthopedic plates to mend bone fractures, for example, are less expensive and reimbursed at a higher rate than imported products in China. Depending on the province, Wego’s reimbursement rate is 15% to 20% higher than the rate for imports. The bottom line for patients: out-of-pocket cost is anywhere from three times to nearly ten times more for an imported plate.

China’s United Imaging offers another example of government support. The company’s CT scan, MRI, and digital x-ray businesses benefit from local tendering policies that favor purchases of domestic products and use authorized lists of recommended local players.

Next Stop: The World

Several emerging-market medtech companies are starting to go global. In France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK, Biosensors is among the largest suppliers of drug-eluting stents. Mindray is the number three supplier of patient-monitoring equipment across the key global markets of China, Japan, Europe, and the US, and Sinocare is number six in the global market for blood glucose monitoring devices. (See the sidebar.)

SINOCARE’S BIG AMBITIONS

Sinocare has set its sights on winning in both the domestic and overseas markets for diabetes care. Shortly after its founding in 2002, the company was having trouble breaking into the local market for blood glucose monitors. Multinationals controlled more than three-quarters of the dominant hospital channel and maintained strong ties with physicians.

Rather than battle head-on with multinationals, Sinocare focused on the fast-growing retail and e-commerce channels. It built a network of 650 sales representatives and 1,200 distributors and established a reach of nearly 100,000 retail stores. Sinocare also opened flagship stores in several of China’s e-commerce channels. These moves have paid off. Sinocare commands a market-leading 28% share of the online channel and sells nearly as much diabetes product in retail stores as Johnson & Johnson does. Sinocare’s overall market share has reached 15%. (See the exhibit.)

The global blood glucose monitoring business has largely become a commodity market. Sinocare has been able to take advantage of this development by buying overseas companies. The company tried to make a big splash in 2015 with its unsuccessful $1 billion offer to buy Bayer’s diabetes care business. Undeterred by the setback, Sinocare bought the US subsidiary of Japan’s Nipro in early 2016 for $273 million. Later in 2016, Sinocare bought PTS Diagnostics, a US company specializing in biometric testing, for $200 million.

These moves have helped Sinocare propel itself to the number six position in the global blood glucose monitor market. About two-thirds of the company’s revenues derive from these acquisitions.

While their market shares are relatively small today, recent history from other industries suggests that emerging-market companies are adept at playing catch-up. (In pharmaceuticals, emerging-market companies have increased their share of global revenues—as measured by the industry’s top 100 companies—by a factor of 26 from 2005 through 2014.) How will medtech companies do it?

External Growth. MicroPort, a Chinese company founded in 1998 to sell stents and other cardiovascular devices, broke onto the world stage in early 2014 when it closed its acquisition of the orthopedic implant business of the US’s Wright Medical for $290 million. The acquisition tripled the size of MicroPort, which now has about 3,000 employees (one-third of them overseas) and recorded first-half 2016 revenues of nearly $199 million. The Wright acquisition also gave MicroPort a US platform on which to expand its non-orthopedic business.

India’s Transasia has made more than ten overseas acquisitions—in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Turkey, the UK, and the US—and exports to more than 100 countries.

Organic Growth. Meanwhile, Biosensors International, based in Singapore but owned by China’s state-owned CITIC Private Equity Funds Management, has focused on organic growth to fuel its expansion. It competes against Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic in selling stents and other products. Notably, Biosensors does not rely on cost advantage. It has invested in clinical trials and in building relationships with physicians and other influencers. In response to market demands, it has also established a direct sales force in several European countries.

Innovation-Led Growth. Increasingly, emerging-market medtech companies are investing in innovation as part of their growth strategies. They recognize that there are limits to what they can achieve simply by providing low-cost, good-enough products. Mindray, for example, consistently spends more than 10% of revenues on R&D, while BGI, China’s largest gene-sequencing operator and equipment maker, devotes more than one-third of its revenues to R&D, double that of its competitor Illumina.

Given their relatively modest revenues and market value, these companies might seem like the mice that roared. Mindray, the largest of the lot, went private in early 2016 in a transaction valued at $3.3 billion. By contrast, Medtronic, the largest pure-play medtech company, has a market capitalization that exceeds $110 billion, and other competitors with nondevice businesses, such as Johnson & Johnson, are even larger.

Nevertheless, these emerging-market companies do have the opportunity to build share in narrow slices of the fragmented industry, to make bold acquisitions, and to diversify into related medtech segments. Multinationals ignore them at their peril.

How Multinationals Should Respond

Many multinational medtech companies are not standing still in the face of the challenge from their low-profile, emerging-market competitors. Learning from the examples of their peers, other multinationals should respond by adapting their product portfolio, reducing costs, localizing their go-to-market approach, and acquiring emerging-market competitors.

Adapting the Product Portfolio. Many multinationals have not yet tailored their product line to the specific needs of emerging markets. The typical multinational medtech product may be too expensive, complex to operate, or encumbered with unneeded bells and whistles. But it would be a mistake simply to produce a dumbed-down version of the standard product line without addressing other elements of the business.

Multinationals need to develop sophisticated customer insight capabilities in their most important emerging markets. Their R&D, business development, and marketing teams in these markets need to work closely together, possibly adopting the iterative, fast-feedback agile approach of software development teams.

GE Healthcare exemplifies this approach. The company has more than 1,000 R&D engineers and seven manufacturing facilities in China. About one-half of its products sold in China were developed in China. Its portable ultrasound devices, for example, are easy to operate and reliable in nonhospital settings, where they are often used by community doctors. One of GE’s portable devices built for China, the Vscan, has also found a home in emergency rooms and ambulances in mature markets.

GE Healthcare has committed $300 million to create its Sustainable Healthcare Solutions business, which is aimed at emerging markets. Recognizing the value of external innovation, the company has also agreed to fund a $50 million incubator that will invest in promising emerging-market health care startups, including disruptive, low-cost technologies.

Reducing Costs. Pricing and costs are top issues globally for the medtech industry, according to BCG’s 2015 commercial excellence benchmarking study. They are especially critical in emerging markets.

If they have not done so already, multinationals should expand their manufacturing and R&D footprints in emerging markets as a way to reduce costs. For products that are not labor intensive, such as stents, local manufacturing will not be a panacea, but it could still lower logistical costs and help avoid tariffs.

Additionally, product simplification should be part of multinationals’ cost strategies. For price-sensitive hospitals and health care providers, durable, no-frills products represent the best value for their limited budgets.

Leading equipment makers, such as GE and Siemens, have been manufacturing a range of products in emerging markets for decades. Their medical equipment businesses have benefited from this decision, with COGS in China lower than the global average.

Localizing the Go-to-Market Approach. Multinationals need a local approach to reaching key buyers, decision makers, and influencers. Emerging markets often have wider geographic dispersion and lower revenue per account, making the commercial economics challenging. What is routine in the West can quickly become frustratingly complex in emerging markets. Creating a winning go-to-market approach requires both strategic insight and execution on the ground.

In China, Medtronic has managed the tradeoff between reach and specialization by basing its sales strategy on city size. For large metropolitan hospitals, each Medtronic business unit has its own sales team because the customers for the products are different. In lower-tier cities, where that approach would be too costly, Medtronic incentivizes sales representatives by allowing them to sell multiple product lines. This approach works because the hospitals in such areas generally have basic needs and because the business unit teams can provide support as required. Of course, more focused companies would likely choose a simpler approach. One size does not fit all.

Acquiring Emerging-Market Competitors. M&A can be an effective strategy for multinationals. Even if they build local facilities, multinationals still may not duplicate a local company’s cost structure. FDA-certified factories and processes, for example, are costly. M&A can allow multinationals to acquire this infrastructure less expensively than they might be able to build it.

M&A can also speed time to market. Many medtech devices require several years to register with the FDA; the acquisition of a company with those registrations in place can bypass the wait. Finally, by making an acquisition, multinationals can enjoy the favorable status of local companies in tendering and requisition processes.

Several multinationals have acquired products, distribution, local R&D, and manufacturing through acquisitions. Philips, for example, acquired manufacturing capabilities when it bought Meditronics and Alpha, two Indian medical imaging companies, in 2008. Medtronic, in 2012, acquired Kanghui, China’s leading orthopedic products manufacturer, as a way to broaden both its portfolio and its channels.

Examples of successful M&A abound, but managing due diligence, cultural fit, talent retention, and integration of acquisitions is challenging. So while this approach can jump-start entry into a market, it can also backfire if not managed carefully.

The history of emerging-market companies shows us that when they set their sights on an industry, they often catch multinationals by surprise. Medtech could be the next to face an unpleasant surprise, unless multinationals learn the lessons of their peers in other industries.