This article is an excerpt from The Most Innovative Companies 2016: Getting Past “Not Invented Here ,” (BCG report, January 2017).

“No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else,” Sun Microsystems cofounder Bill Joy observed more than a quarter century ago. Since so much of innovation today is rooted in technology, especially digital technology, Joy’s Law presents companies with a double-barreled conundrum. How (and where) do they look for the best ideas, and how (and where) do they turn those ideas into business realities with significant revenue streams? Here we examine the second question, specifically the rise of new models and vehicles for developing external innovation and the need to manage both internal and external sources. (For a consideration of the first question, see the companion article “ Casting a Wide Innovation Net .”)

The External Innovation Imperative

Companies have long incorporated external innovations through a variety of mechanisms, including acquisitions, partnerships, joint ventures, and licensing. But the technical basis of so many innovations today has increased both the need to access new technologies and capabilities from outside the company and the variety of models for doing so, including corporate venture capital , accelerators and incubators, and innovation labs. And regardless of the source of the innovation, many companies must still overcome the not-invented-here mentality when they attempt to bring a new idea, capability, or model into their organizations.

Self-described strong innovators in BCG’s annual global survey on the state of innovation have long used multiple channels to gain access to new ideas, capabilities, and technologies. The most direct are mergers and acquisition, and licensing. Cisco Systems (number 25 on our 2016 list of the 50 most innovative companies), for example, has stayed ahead of the networking technology curve in part by making more than 175 acquisitions since 1993—almost eight a year. Facebook (number 9) paid a total of $3 billion for Instagram and Oculus VR within a couple of years of its own IPO. General Motors (number 27) has made two major investments in tech startups in 2016. The $11 billion acquisition of Pharmasset by Gilead Sciences (number 23), the highly innovative pharmaceutical company that we profiled in our 2015 report, was pivotal for the development of Sovaldi and Harvoni, breakthrough treatments for hepatitis C.

Joint ventures, partnerships, and collaborations are another avenue. Several automakers have established partnerships with tech companies to work on autonomous vehicles: Fiat Chrysler with Google, GM with Lyft, and Volvo with Uber are three examples. Collaborations often involve a geographical element, following a variation on Willie Sutton’s explanation of why he robbed banks—companies go where the ideas are. Walmart opened a tech lab in Silicon Valley in 2011; it has since been joined there by multiple major retailers. GE has invested more than $1 billion in a software “center of excellence” in San Ramon, California. Most of the top ten pharmaceutical companies have a major research presence in and around Cambridge, Massachusetts, a hub for biomedical innovation.

The Resurgence of Innovation Models and Mechanisms

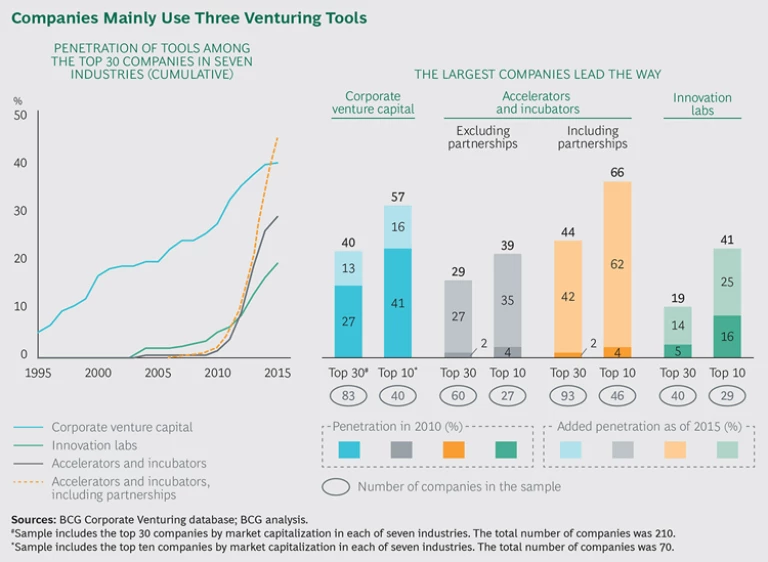

In recent years, many companies have rediscovered a broad variety of models for external innovation, taking a page from the success of venture-backed startups that have disrupted multiple industries, including not just technology but also financial services, media and entertainment, travel and tourism, and marketing in general. Corporate venture capital (CVC), accelerators and incubators, and innovation labs are again becoming more common, especially among large companies. BCG’s analysis of 210 top firms—the 30 largest companies in each of seven industries (automotive, chemicals, consumer goods, financial services, media and publishing, technology, and telecommunications)—found significant increases in the use of all three mechanisms between 2010 and 2015. (See Corporate Venturing Shifts Gears , BCG Focus, April 2016.) (See the exhibit.) The rapidly increasing pace of change and the proliferation of new technologies are making these new models competitive necessities, not optional activities.

CVC and incubation have come and gone over the years, but past efforts often lacked a strong link to the sponsoring company’s strategy. This wave of alternative innovation vehicles is much more tightly focused on responding to disruptive trends and enabling new business models or extending companies’ current capabilities. The new models are more closely and thoughtfully linked to the sponsoring companies’ corporate and innovation strategies and existing innovation systems.

Industry context often determines which approach is best. The speed of innovation, for example, varies from one industry to the next. Where innovation momentum is high and the need for innovation is great, such as in technology and apparel, companies predominantly use accelerators and incubators. In contrast, where the pace of innovation is somewhat slower, such as in chemicals, companies turn mainly to CVC.

Each vehicle serves a different kind of function, so companies need to decide which to deploy and their specific role in the innovation development chain. So far, there is no empirical validation that one model is better than another. In an analysis of the impact of six external innovation avenues on R&D productivity in biopharma, for example, we found that all had so far yielded equivalent returns. While the evidence is still emerging on what model is best in a given situation, we can glean some lessons from what companies are currently doing.

Corporate Venture Capital. Among the 30 largest companies in BCG’s seven sample industries, the use of CVC increased from 27% in 2010 to 40% in 2015. Among the top ten companies in each sector, it has jumped from 41% to 57%. Companies use venture investments to gain minority positions in startups and an early understanding of new markets, trends, and technologies. Some companies pursue CVC primarily for financial gain, but for many, the investments are strategically focused on furthering innovation. Companies pursuing CVC are split between those that control their investments from the center and those that empower business units to direct them.

In the past three years, both strategically and financially oriented CVC units have focused on the software industry, reflecting the increasing value of data as the trends toward digitization and virtualization gather speed, furthering the transformation of hardware to software. The value of CVC investments in software by the top 30 companies now surpasses the value of their investments in all other target industries combined.

Accelerators and Incubators. The use of accelerators and incubators has increased from 2% to 44% among the 30 largest companies in the seven industries and from 4% to 66% among the ten largest. Successful accelerators and incubators typically do not operate in a vacuum; they form partnerships with venturing operations from other corporations or team up with independent accelerators or incubators. The partners often have a common interest in specific fields. Accelerators and incubators typically focus on early stages of the innovation process.

Innovation Labs. The use of innovation labs has increased from 5% to 19% among the top 30 companies and from 16% to 41% among the top ten. Corporations tend to employ these labs further along the development chain to accelerate time to market. They are in-house units designed to complement—not supplant—conventional R&D and often interact closely with external entrepreneurs. In effect, such labs try to operate as startups, with all the speed and agility that characterize the breed. The main focus of innovation labs tends to be on advancing products or services that are close or adjacent to the core business.

How One Company Excels

One of the strongest longtime innovators in any industry is Johnson & Johnson, a regular member of the BCG most innovative companies list and number 29 in 2016. According to Paul Stoffels, the executive vice president and chief scientific officer, there are at least three reasons for J&J’s innovation success:

- The company focuses on high-impact medical breakthroughs—“You have to bring the right technologies forward,” Stoffels says.

- J&J gives equal weight to internal and external innovations and actively encourages its scientists to connect with the outside world—“You have to realize that you are not the only smart company out there,” he notes.

- Management makes sure that innovation programs are strategically aligned with the company’s business objectives.

J&J employs a full range of innovation vehicles, especially early in the development chain. Each vehicle is suited to a particular stage and a specific goal: incubators for young ideas, innovation labs for companies that are looking to mature, and venture capital when the constraints are related to funding. As Stoffels puts it, “You need a system, and you need to make sure that it is strategically aligned with your objectives.”

The company’s JLABS in San Francisco, South San Francisco, San Diego, Houston, Toronto, and Boston provide flexible incubator services for 150 high-potential young firms whose work has not yet entered clinical development. J&J screens approximately ten companies for each one that’s accepted. “These companies can count on us for input and support to the extent they want it,” Stoffels says. “But they don’t have to accept anything.”

J&J’s six innovation labs provide services for companies at a slightly later position: those just entering clinical development. These labs are empowered to make deals that connect these companies directly with J&J’s business units.

The company’s venture capital arm has more than 80 investments in young companies. In Europe, where access to funding is often coupled with the challenge of access to lab space and capabilities, the company combines these services in its JLINX centers.

J&J works hard to ensure that external innovations are seamlessly meshed with internal ones. It rewards internal unit leaders equally, whether innovation originates inside or outside. “Everything gets the same credit,” Stoffels notes. Internal research scientists are evaluated on whether they stay abreast of developments in their fields and help identify the most promising external work being done—in industry, academia, or elsewhere. According to Stoffels, “We expect our people to know well what’s going on and what they need to go after.”

The bottom line is that the company’s internal scientists are still crucial to J&J’s success, despite the company’s external focus. “You can’t have good external results without strong internal scientific capabilities,” Stoffels says.

The Importance of Incentives and Rewards

J&J’s approach to assigning credit for innovation highlights a big issue for many companies. The challenge is often not just how to source innovations externally but how to keep the internal organization from killing them off. When individuals are measured and rewarded on “their output,” and that output doesn’t include things from the outside, external sourcing becomes more difficult than it should be.

Scientists at one large pharmaceutical company that has such an incentive system recently resisted licensing a new molecule because they had been working along similar lines and saw the molecule, which performed better than the in-house version, as competition. Instead, internal researchers should get credit for successfully developing ideas from the outside. But that’s only the minimum—companies should also think about incentives for the internal organization to be active in scouting new ideas and cultivating new-idea generators.

Resistance to ideas “not invented here” is a cultural problem, and corporate cultures can be difficult to change. There are some things that companies can do quickly, however, to make their organizations more receptive to external innovations.

Set the right incentives and metrics. As we’ve noted, companies can do a lot to mitigate internal resistance by putting in place incentives that reward innovations when they take hold, regardless of the original source. They can also make sure that contributions to the success of innovations, internal and external, are measured and rewarded.

Send employees out. Corporate infrastructure that exposes employees to outside influences and ideas through attendance at conferences, membership in professional societies, and similar activities can help break down insularity. Again, employees’ involvement in such areas can be measured and rewarded, if not monetarily then through recognition and corporate support.

Set the tone at the top. Acknowledgement from the C-suite of successful innovations, particularly external ones, can send a powerful message that the not-invented-here syndrome will not be tolerated and that productivity and success will be recognized no matter where they originate.

Successful companies develop innovation models and systems that are suited to their circumstances and reflect their corporate strategies. The repeated presence of companies such as J&J, General Electric, 3M, and IBM, among others, on our list of the 50 most innovative companies suggests that successful innovators also adapt their models and systems to changing times. As the pace of science and technology advancement increases, the ability to continually adapt models to successfully access and incorporate outside ideas, inventions, and tools will become even more important.