India is still a growth story—a big growth story. Even assuming conservative GDP increases of 6% to 7% a year, we expect consumption expenditures to rise by a factor of three to reach $4 trillion by 2025. India’s nominal year-over-year expenditure growth of 12% is more than double the anticipated global rate of 5% and will make India the third-largest consumer market by 2025.

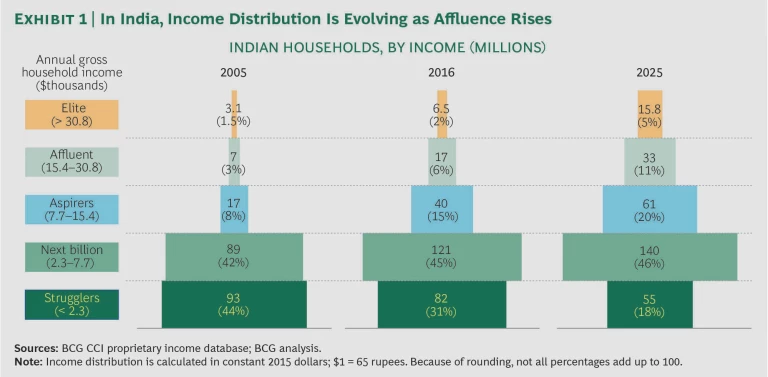

Rising affluence is the biggest driver of increasing consumption. (See Exhibit 1.) Of India’s five household income categories (elite, affluent, aspirers, next billion, and strugglers), the top two income classes are the fastest growing. From 2016 through 2025, the share of elite and affluent households will increase from 8% to 16% of the total while the share of strugglers will drop from 31% to 18%.

Behind the growth headlines is an even more important story: consumer behaviors and spending patterns are shifting as incomes rise and Indian society evolves. These shifts have big implications for how companies position themselves now.

In 2012, BCG’s Center for Customer Insight (CCI) conducted its first in-depth exploration of growth and consumer trends in India. (See The Tiger Roars: Capturing India’s Explosive Growth in Consumer Spending, BCG Focus, February 2012.) In 2016, we took an updated look at emerging developments, basing it on new research among 10,000 consumers in 30 locations nationwide. The evolution in consumer behaviors is playing out largely as we predicted four years ago, but, inevitably, new developments, as well as twists and turns, are affecting consumer attitudes and consumption.

This report examines the factors that are shaping India’s complex and growing market, consumers’ evolving spending patterns, the increasing and substantial impact of digital technologies on spending, and emerging trends that could alter spending. It presents an assessment of how companies need to adjust their strategies and models to meet shifting circumstances.

The Factors Shaping a Growing Market

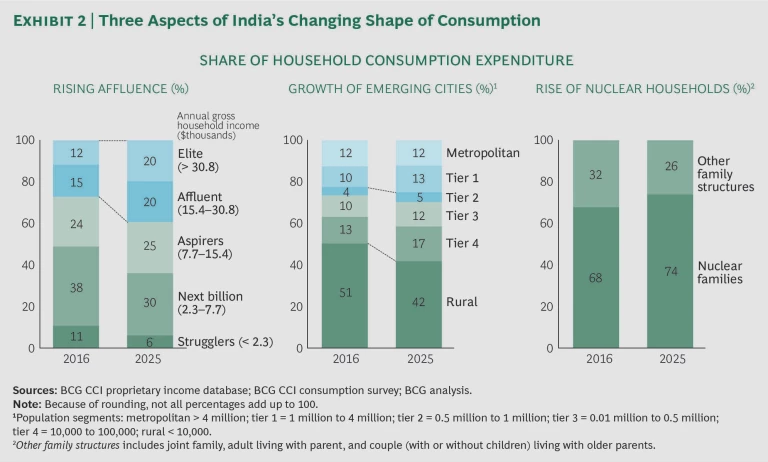

Companies today need to focus on three aspects of India’s fast-growing consumer market: rising affluence, the country’s continuing and unique pattern of urbanization, and fundamental shifts in family structures. (See Exhibit 2.)

Rising Affluence. We observed in 2012 that India’s income pyramid was transforming itself into a diamond as household incomes grew. In terms of spending, the two top consumer categories—elite and affluent—will become the largest combined segment by 2025, accounting for 40% of consumption compared with 27% in 2016. Within this segment, the urban elite and affluent are fueling most of the growth. By 2025, wealthy urbanites will be responsible for one-third of total consumption. The share of the next billion and strugglers will shrink from 49% in 2016 to 36% in 2025.

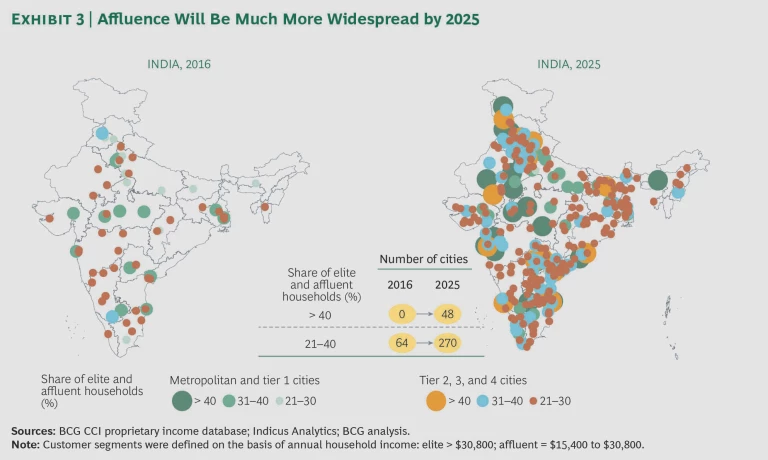

Continuing Urbanization. India’s continuing pattern of urbanization is uniquely Indian. The migration to urban centers is not concentrated in a few cities as it is in countries such as Indonesia or Thailand; nor is urbanization in India occurring as quickly as in China. In India, the population is booming in scores of small cities across the country. About 40% of India’s population will be living in urban areas by 2025, and these city dwellers will account for more than 60% of consumption. Much of this growth will take place in small towns. (See Exhibit 3.)

In terms of consumption expenditures, emerging cities (those with populations of less than 1 million) will be the fastest growing. Fueled by rising affluence, expenditures in these cities are rising by nearly 14% a year, while consumer spending in India’s biggest cities is increasing at about 12% a year. We expect emerging cities to see the highest growth in the number of elite and affluent households through 2025. By then, the number of such households will have increased by a factor of more than 2.5 in emerging cities, while it will have almost doubled in major metropolitan areas. Furthermore, some 120 cities will have matched today’s major metropolitan areas in average household income.

Consumers in emerging cities behave differently from the big-city consumers. They have a strong value-for-money orientation, significant local cultural affinity, and a more conservative financial outlook. They have high purchasing aspirations but are often constrained by product availability. Emerging cities of similar sizes and growth rates differ from each other and from metropolitan centers in just about all other respects. It would be a mistake to approach consumers in these cities as a homogeneous group. In addition, as the cities grow larger, companies will need to segment further within each one, to identify small areas of opportunity. (See “Small Pockets of Big Opportunity.”)

SMALL POCKETS OF BIG OPPORTUNITY

Despite India’s extraordinary diversity, marketers have historically employed a broad-brush regional approach based on zones, regions, or city tiers. (See “Street-Level Segmentation in India: Winning Big by Targeting Small,” BCG article, December 2015.) This approach has severe shortcomings, as these broad regional cuts cannot capture India’s diversity or the substantial pockets of affluence that exist throughout the country. For example, a significant proportion of India’s elite and affluent families live outside major metropolitan centers.

The best opportunities in major metropolitan areas may be concentrated in a small set of micromarkets, depending on the consumer segment that a company wants to reach. For example, some 40 (of 97) micromarkets in Mumbai are home to 80% of the city’s elite and affluent households. Of those 40, 14 have 80% of the city’s premium clothing stores and 25 have 80% of the premium electronics stores. Similar breakdowns can be applied to New Delhi and other major cities.

Many attractive micromarkets can be found outside the big metropolitan centers: 22 of the top 50 micromarkets in India (measured by the number of elite and affluent households), including 5 of the top 10, are in small cities. To identify the real pockets of opportunity, marketers need to apply a sophisticated approach to regional segmentation.

Shifting Family Structures. As we also noted four years ago, the extended Indian joint family has given way to nuclear households, which we define as a couple or a single person, with or without children. The proportion of nuclear households, which has been on the rise during the past two decades, has reached 70% and is projected to increase to 74% by 2025. This ongoing shift is significant to marketers because nuclear families spend 20% to 30% more per capita than joint families.

Decision makers in nuclear households—younger and more optimistic than those in joint families—base their consumption decisions more on lifestyle considerations and the need to “keep pace” than on the need for functional necessities, especially in such categories as consumer durables and apparel.

Spending Patterns Evolve

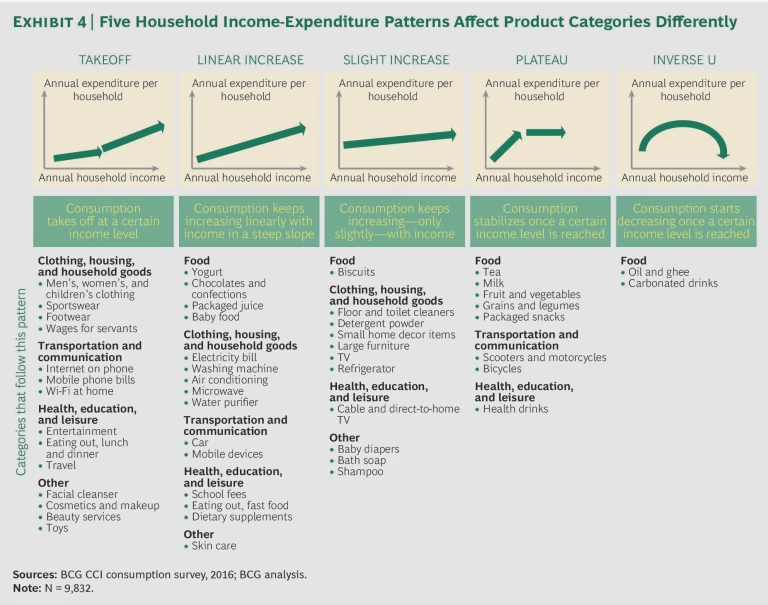

Rising incomes affect spending patterns in various categories differently. Certain categories (and subcategories) become more or less relevant to consumers as their incomes increase. The BCG CCI’s most recent consumer survey in India studied consumption in more than 50 categories that fall into three broad purchase groups: high-frequency items (such as food and beverages, personal-care products, entertainment, and telecom products and services), medium-frequency items (apparel, home furnishings, and tourism, for example), and low-frequency items (such as consumer durables, cars, and appliances). We have found that the classic S-curve growth pattern does not always hold true and that different categories exhibit very different growth trajectories. The study revealed five broad categories of correlations between rising income levels and expenditures. (See Exhibit 4.) The categories reflect the following consumption-income relationships:

- Consumption takes off at a certain income level.

- Consumption increases linearly with income.

- Consumption increases slightly with income.

- Consumption stabilizes after a certain income level is reached.

- Consumption decreases after a certain income level is reached.

A clear understanding of these correlations helps identify a growth trajectory for each of these categories and subcategories. In many cases, historical growth is not a good predictor of the future. For example, mobile-phone sales and mobile internet connections are likely to show disproportionately high growth rates over the next decade as incomes rise quickly. TV sales, on the other hand, increase only slightly with rising incomes, so they are more likely to maintain their historical growth trajectory.

Our analysis highlighted three themes.

Shifting Growth Drivers. Traditionally, for many consumer categories, increasing market penetration has been the biggest driver of sales growth. But this is set to change as frequency of purchase and spending per purchase occasion rise in importance. There is a shift toward higher-quality, higher-price subsegments within categories, as Indian consumers trade up with greater frequency and enthusiasm. Our survey suggests that 30% of consumers in India are willing to spend more on products that they perceive are “better”—a much higher percentage than is found in more developed markets such as the US, Germany, and the UK.

The impact of penetration, frequency, and spending per purchase varies across categories. For example, in women’s apparel, elite and affluent consumers spend nine times and five times more, respectively, than a struggler. The difference is mostly a matter of higher spending per purchase; differences in product penetration and purchase frequency are not significant. Or take eating out. Elite and affluent householders spend 35 times and 13 times more, respectively, than strugglers in this category. All three factors contribute: increase in penetration, frequency of occasion, and spending per purchase.

Potential for Trading Up in Emerging Cities. Across all income segments, consumers in major metropolitan centers and tier 1 cities (those with populations of more than 1 million) spend more than their counterparts in other locations. This is true for basic categories (such as laundry detergent powder and biscuits) and for more discretionary categories (such as eating out and the mobile internet). Higher spending levels in big cities are not the result of greater product penetration, as penetration for a given income segment is generally similar across cities. Consumers in big cities, on average, buy more premium products, which leads to higher spending. This represents an opportunity for companies that make more premium products available—and can convince buyers of their value—to boost growth by encouraging consumers in small cities to trade up.

Changing Spending Behaviors. Our research shows a steady and progressive shift in consumers’ aspirations and spending behaviors—in certain categories. For one thing, shopping is becoming more social—involving all family members—and much more frequent, thanks to the rise of online shopping. For another, many consumers are making different buying and tradeoff decisions. For example, immediate gratification is becoming more important than asset creation. Also, the biggest desires of aspirer households used to be to own a house and a car. Today, many more of these consumers want to take international vacations. Similarly, affluent households are becoming comfort seekers, and they are willing to pay for it.

Aspirer households are also trading up more frequently in categories such as apparel, buying better brands for everyone in the family. Social media have played a big role. People want to fit in with their peers. At the same time, consumers in numerous basic categories (such as biscuits, salty snacks, tea, and kitchen and floor cleaners) are far less conscious about the brands. (See “Changing Spending Behaviors: Profiles of Two Aspirer Households.”)

CHANGING SPENDING BEHAVIORS: Profiles of Two Aspirer Households

The evolving circumstances, behaviors, aspirations, and consumption patterns of Indian consumers are evident in a comparison of aspirer class families with whom we spoke during our research for our 2012 and 2017 reports.

2011. Shabahat and Nishat Fatima. When we met Shabahat, aged 39, his wife, Nishat Fatima, 30, and their two children, 11 and 9, in 2011, Shabahat was a secondary school teacher and Nishat Fatima, a housewife.

They lived in a two-bedroom apartment, owned by Shabahat’s father, in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. Their annual household income ranged from $8,500 to $9,000, and their consumption expenditures totaled 70% to 80% of their income.

Their consumption expenditures broke down as follows:

- Food. 30% to 35%

- Education and Leisure. 15% to 20%

- Clothing. 10% to 15%

- Transportation and Communication. 10% to 15%

- Housing. 10% to 15%

- Health Care. 5%

- Other (Including Personal Care, Loan Repayments, Socializing). 10% to 15%

The family told us that they bought branded clothing only for their children. Shabahat and Nishat Fatima shopped mainly in local shops and at the bazaar.

The family had high aspirations for the future. Shabahat was looking for better job opportunities in other schools. His dream was to buy his own house and furnish it according to his own tastes and preferences rather than those of his parents. Shabahat and Nishat Fatima also hoped to buy a car and trade up to better brands of clothing.

2016. Abhishek and Radhika. Abhishek, 35, his wife, Radhika, 32, and their two children, 8 and 6, were living in their own free-standing house in the Nizamuddin West area of New Delhi. Abhishek was working as a manager in a pharmaceutical company; Radhika was a housewife. Their annual household income ranged from $14,000 to $15,000—more than 60% higher than that of Shabahat and Nishat Fatima in 2011. They were spending more as well, but their expenditures represented a smaller share of their income (65% to 75%), which means that they were saving more.

By consumption category, Abhishek and Radhika were spending about the same share (30% to 35%) on food as Shabahat and Nishat Fatima were in 2011, but their spending on packaged food represented 10% to 12% of their total consumption. They were spending more (of a larger base) on education and leisure (20% to 22%) and other categories, including personal care, loan repayments, and socializ-ing (15% to 20%). The shares of spending on clothing, housing, and health care were about the same, but the amounts were higher because of their higher income. They were spending less (8% to 12%) on transportation and communication.

Within categories, their spending patterns were different from those of Shabahat and Nishat Fatima. In 2016, the discussion with Abhishek and Radhika covered a wide range of brands for apparel and footwear that they had considered, or bought, for the entire family and not just for their children. Similarly, in 2016, Abhishek and Radhika were doing much more of their shopping at branded stores and a premium grocery chain.

Abhishek and Radhika hope to visit exotic locations for vacations; they especially want to visit Switzerland in the coming years. They also want to make a comfortable life for their kids and fulfill their daughter’s love for new dresses and their son’s for new toys.

The Roar of the Digital Tiger

As we have emphasized in previous articles and reports, the internet is an increasingly pervasive factor in India’s commerce, and its influence will only expand. (See The Rising Connected Consumer in Rural India , BCG Focus, August 2016, and “ The Changing Connected Consumer in India ,” BCG article, April 2015.) This is true for all manner of urban and rural consumers. Nationwide, internet penetration rose from 8% in 2010 to almost 25% in 2016. It is likely to grow to 55% or more by 2025, when the number of users will likely reach 850 million. The composition of the user base is also changing. Most of the digital focus to date has been on urban users, but rural areas will see much of the action for the rest of this decade. We expect that more than half of all new internet users will be in rural communities and that rural users will constitute about half of all Indian internet users in 2020. Users are older and more mature. Today, more than half of all users are 24 years old or younger, but by 2020 about 65% of users will be 25 or older. Companies need to consider three aspects of rising digital penetration and its increasing influence on consumption patterns.

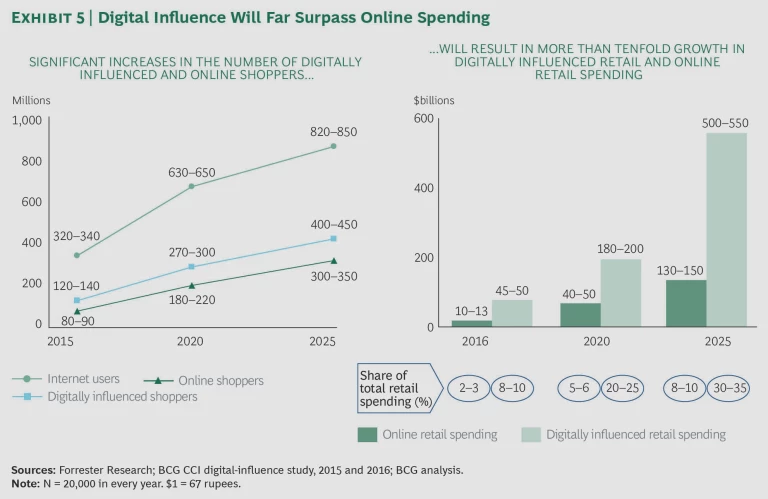

Online spending is taking off. In the past three years, the number of online buyers has increased sevenfold to 80 million to 90 million. Continued growth in internet penetration and rising e-commerce adoption will drive further growth in the number of online buyers. Multiple factors are behind the rising adoption of e-commerce channels. These include the strong value proposition offered by online merchants, proliferating payment platforms, strengthening delivery logistics, and significant financial investment in the sector. On the basis of these and other factors, we anticipate that the number of online buyers in India will climb to 300 million to 350 million by 2025. In terms of value, online commerce is still a small portion of total retail sales, but it is growing fast. With the increase in online buyers, we expect the total value of e-retail to reach $130 billion to $150 billion, or 8% to 10% of total sales, by 2025. (See Exhibit 5.)

From the consumer’s perspective, convenience will remain the primary factor driving this growth. Almost 60% of online shoppers rate convenience as a key reason to shop online, and the value of convenience keeps rising as consumers increase their online shopping. Discounts are another popular feature for more than half of online shoppers (especially lighter online shoppers), and availability and assortment of merchandise are important to more than one-third. Trust in showrooms remains the biggest barrier (after basic access) to shopping online, followed by difficulty in website navigation and fear of fake products.

Digital’s influence on broader consumer spending is significant and growing rapidly. Online spending alone doesn’t begin to capture digital’s growing influence. Digitally influenced spending is currently about $45 billion to $50 billion a year, and that figure is projected to increase more than tenfold to $500 billion to $550 billion—and to account for 30% to 35% of all retail sales—by 2025.

The extent of the internet’s influence on consumer decision making and behaviors will be constrained only by the rate of increase in internet penetration. Already, a rising number of consumers in all segments are using the internet as their first port of call in framing and driving their purchase decisions. Our research has found that about 70% of those who have access to the internet go online to make informed purchase decisions. This number varies among categories of products and services, but it is on the rise everywhere. Consumers climb the learning curve quickly. As they get more comfortable with digital capabilities, their usage patterns exhibit growth that belies age and other demographic variables.

While digital influence is growing across all income classes, locations, and age groups, the impact in rural areas is especially dramatic. Indeed, rural consumers may leapfrog their urban counterparts and adopt digital behaviors much more quickly. Less expensive mobile handsets, the spread of wireless data networks, and evolving consumer behaviors and preferences will drive rural penetration and usage, changing how rural consumers interact with companies and giving companies many more options for engaging with them.

All that said, different categories will evolve differently. For example, we expect 65% to 70% of sales in, say, consumer electronics to be influenced digitally by 2025, while the impact in other categories, such as fast-moving consumer goods, will be much lower, in the range of 25% to 30%, thanks to different starting positions and inherent category characteristics.

Omnichannel interaction is increasingly important, but its significance varies by category. Consumers’ purchase pathways are increasingly complicated. Consumers today regularly crisscross online and offline touch points in their purchase journeys, and, as a result, multiple types of pathways are emerging. The extent of offline-online interaction varies significantly by category. For example, in mobile phones, almost 50% of buyers who have access to the internet use both online and offline touch points in their purchase journeys. By contrast, in fast-moving consumer goods, almost all transactions are completed either entirely offline or entirely online. The experience of other markets shows that consumers will expect a more seamless experience as they navigate through various touch points and among different channels.

Almost three-quarters of urban internet users today use only mobile phones to access the internet, compared with 52% in 2014. Falling smartphone prices, less expensive data packages, and the availability of more mobile-friendly content are all driving this growth. The numbers are even higher for young age groups, new internet users, and lower-income segments. Among rural users, a mobile phone is the primary online device: 87% of connected rural consumers use only their phones to access the internet.

As a result, mobile commerce is becoming the dominant force behind e-commerce growth. Eight of ten urban e-commerce transactions take place by phone—across categories, income segments, and regions. The lack of alternative devices, the ability to make transactions on the go, and additional discounts offered on transactions made through apps all contribute to this growth. The dominance of mobile commerce spans consumer segments as well as product categories, including high-ticket purchases. One significant ramification is the large number of unplanned or impulse purchases that people make on their mobile phones. Many consumers use apps for browsing in their free time, and often this browsing leads to purchases induced by an attractive offer. As many as 40% of all transactions conducted on smartphones are unplanned or impulse based.

Bets for the Future

As in many other countries undergoing rapid development and change, emerging trends in India are affecting consumers’ behaviors and consumption patterns. Some are passing fads that may end up having limited impact. But several bear watching because they have the potential to lead to significant changes over the next decade.

Time Compression. A combination of factors such as shrinking family support structures and fast-paced work have combined to create a heightened sense of time compression—the need to perform increasing amounts of work within a given time period—for many Indian workers. Multiple studies have placed Indian workers among the most stressed in the world. The most visible (and not always positive) manifestation of this trend is multitasking—talking on the phone while driving, for example, or checking e-mail while having dinner with friends.

Time compression has far-reaching consequences. It is driving exponential growth in several categories, such as ready-to-cook or ready-to-eat products. The ready-meal market in India has been growing at rate of 30% annually for several years, more than tripling from $35 million in 2010 to more than $120 million in 2015. Time compression is also behind a new set of business models that focus on convenience and offer end-to-end solutions.

The Rising Appeal of Indian Goods. Quality and luxury used to be the purview of imports. As recently as a decade or two ago, many Indians looked forward to their relatives’ bringing chocolates, perfumes, or even brand-name shoes from abroad. Times have changed: today 60% of Indians are willing to pay extra for products that are made in India.

Moreover, across all kinds of categories, Indian consumers are exhibiting increased curiosity and excitement over exploring local roots. They are interested, for example, in natural products in personal care, local flavors in packaged food, and hand-woven fabrics in clothing. The bundi sleeveless jacket is back in vogue; in fact, Time magazine has ranked it among the top ten political fashion statements worldwide. Fabindia, which describes itself as “India’s largest private platform for products that are made from traditional techniques, skills and hand-based processes,” is among the largest and most profitable retail-apparel brands in the country. Forest Essentials, advertising itself as “the quintessential Indian Beauty Brand,” has grown into an international premium personal-care company, with Estée Lauder taking a stake.

The (Almost) Me, Myself, and I Generation. While the nuclear family may seem to be India’s new normal, the future could see a further shift in household composition—from nuclear-family to singles households. The number of single people in the workforce has steadily increased. From 2001 through 2011, the average age at marriage rose from 22.6 to 28 for men and from 18.3 to 22.2 for women. During that period, the number of single women over the age of 20 increased by 40%. So far, this remains largely a big-city phenomenon, but it has started percolating down to tier 2 cities.

This change in family structure is having far-reaching implicatons for income and spending as young single men and women base their consumption decisions more on lifestyle considerations than on functional needs. Anecdotal evidence and parallels from other countries indicate that these singles are more individualistic, but they also think of communities (physical and virtual) and causes (social and political) as proxies for families.

Women Taking Their Rightful Place. Women in India, urban and rural, are exercising greater influence on their families and society. Several forces—including new electoral rules, better health care, and greater media focus—are behind this change. The most important factor, however, is educational opportunity. From 2005 through 2014, the enrollment rate of girls in secondary education increased from 45.3% to 73.7%, and it’s now higher than that of boys. Young women have bridged the gap in higher education too: their enrollment rate now stands at almost 20% while that of young men is 22%. This shift will not only result in greater overall literacy levels but will also have a broad impact on such societal factors as workforce demographics and economic independence for women.

New Imperatives for Companies

As India’s consumer market continues to grow and the factors described above take shape, companies will need to shed conventional wisdom (for example, that opportunities lie in big cities and at the bottom of the pyramid or that India is a male-dominant society) and adapt their business models to meet changing consumer needs and behaviors. Although many companies are already reacting, they have yet to develop explicit plans that address the changes underway. Companies should take several steps immediately.

Find the opportunities at every price point. In the past, India was a large mass market characterized by low unit prices. Today, however, there are large-scale markets across all price tiers for most consumer categories. Companies need to choose between straddling the full spectrum and focusing on select segments.

Identify the breakout opportunities. While India as a whole is a growth story, certain market segment pockets—emerging cities, micromarkets within cities, and categories that benefit particularly from rising incomes—are showing breakout growth. Companies looking to capitalize on India’s growth story need to identify the high-growth segments and pockets for their brands and products.

Develop an omnichannel strategy that is appropriate for the category. Digital is going to play a central role in how Indian consumers decide what they will buy and how. The exact extent of digital’s influence will vary across categories, but its overall impact will be both broad and deep. Consumers will expect a seamless experience as they navigate a complicated purchase pathway. Companies need to think beyond e-commerce: because digital’s influence is much larger than simply online spending, companies must be prepared to offer an online and offline experience that is appropriate to the category and meets consumers’ rising expectations. For example, in a category such as autos, companies need to ensure that they make use of all the online data they can harness in order to create targeted offerings for consumers when they reach the dealer. In apparel, a category that involves lots of online purchases, the challenge is to ease the buying process and present purchase options and offers when and where the consumer wants to buy.

Plan for changing social norms. India is experiencing many societal changes, including the expanding role of women, increased individualism, shifting roles within families, and rising national pride. These shifts have the potential to fundamentally alter how Indian consumers spend. Companies operating under old notions should keep their eyes and ears focused on the changing reality. Dealing with the changes may require companies to fundamentally rethink their business models, including product offerings, consumer engagement, and marketing.

As companies reimagine themselves along these and other lines, they should make two key adjustments. First, they should change their notion of the market and competition. Widespread digital adoption has allowed many smaller players and unconventional competitors to disrupt sectors and tip the scales to their advantage. Multiple startups that focus on solving specific consumer needs have already emerged, and their digital business models enable them to expand quickly. Companies need to stay ahead of the curve, developing their own innovative offerings for consumers and staying agile enough to change effectively. Second, they should react to the changing nature of the relationship between the consumer and the company. More information, greater transparency, and the amplified voice of the individual through social media mean that consumers are gaining the upper hand when it comes to buying decisions. To stay ahead, companies must continually develop superior propositions and manage consumer advocacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Indira Ghagare, Sur Shah, Vivek Khetan, and Divya Sharma for their assistance in developing this report.

They also thank Belinda Gallaugher and Raghuram Godavarthi for helping to coordinate the report; David Duffy for his writing assistance; and Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Elyse Friedman, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to its editing, design, and production.