Women are underrepresented in many global companies, particularly among senior leadership teams—and companies are missing out on opportunities as a result. A large and growing body of research shows that organizations with greater numbers of women, especially in leadership roles, perform better. For example, a 2016 Peterson Institute for International Economics study of some 22,000 global companies found that as companies increased the number of women among board members and senior leaders, their profit margins increased as well. Diverse teams bring diverse perspectives to a company, improving both problem solving and resiliency and making the organization more innovative and adaptable to change. (See “ Diversity at Work ,” BCG article, July 2017.)

Yet when companies try to fix this problem, they often center their efforts solely on women. Experience shows, however, that this is not enough to bring about material change. Such a narrow focus essentially walls off gender diversity as a women-only issue instead of positioning it as a broader topic that has a significant effect on overall company performance. What’s more, at most companies, women who try to generate meaningful change on their own find that they are too few in number to produce the necessary impact. Men need to join their efforts in order to succeed.

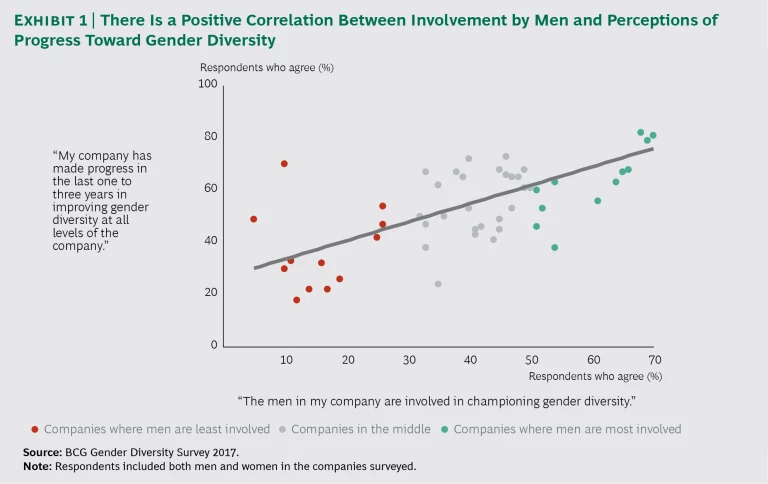

BCG has been studying gender diversity at organizations around the world for the past several years. A key finding from our research is that the career obstacles women face, such as being overlooked for promotions, tend to be institutional, with deep roots in the organization’s culture. Many women stall out in middle management—or step off the career track entirely—not because of explicit discrimination or lack of ambition but rather because of many small factors and daily hassles. (See “ Dispelling the Myths of the Gender ‘Ambition Gap ,’” BCG article, April 2017.) Reforming this culture and creating true gender parity requires participation by both men and women, particularly given that the senior leadership team at many companies is predominantly male. The good news is that when men do become directly involved in gender diversity, both men and women believe that their company is making much greater progress in achieving gender parity. (See Exhibit 1.) Worldwide, our data shows that among companies where men are actively involved in gender diversity, 96% report progress. Conversely, among companies where men are not involved, only 30% show progress.

Creating true gender parity requires participation by both men and women.

Men Tend to Have a False Sense of Progress

It seems intuitive that involving men, and thus increasing the number of people who support gender parity initiatives, would lead to greater results. Yet part of the challenge of getting men to join the efforts, according to our data, is that they tend to overestimate how well their company is doing in terms of gender issues. When asked whether their organization has made progress in gender diversity over the past one to three years, men were, on average, 12 percentage points more likely to say yes than women. Men also tend to overestimate their personal involvement in such efforts by an average of 17 percentage points. In some major markets—Australia and India, for example—men rate their involvement substantially higher than women do, by 20 percentage points or more.

Demographic shifts are likely to compound the issue. Most of the people entering the workforce today are millennials, who are soon to become the biggest population cohort and to constitute the largest share of the workforce at most organizations. Many millennials expect to be part of a dual-career household, where both spouses will need to balance work and family commitments. And they are more likely to see a company’s stance on gender diversity as a marker for the overall experience of working there.

Five Ways for Men to Get Involved

The formula for gender diversity is clear. (See Getting the Most from Your Diversity Dollars , BCG report, June 2017.) And a central thread running through all diversity initiatives is that the involvement of men is crucial to generate progress. Companies simply cannot succeed unless they make gender diversity an organization-wide initiative and men step up to take part. Men can become involved in five ways. (See Exhibit 2.)

Support flexible-work policies. Across all 21 of the markets we examined, offering flexible work—which includes part-time employment, remote work, parental leave, job sharing, and additional unpaid vacation—is the most effective way for companies to create a gender-balanced workforce. Many companies have flexible-work programs in place, but they are often underutilized or used by only a limited group of employees, such as mothers with young children.

Offering flexible work is the most effective way for companies to create a gender-balanced workforce.

But flexible work will never become a realistic option for all unless men explicitly support it, and they can do so in two ways. First, men themselves need to take advantage of these programs, by working remotely, working part-time, or taking full parental leave, for example. In dual career households especially, flexible-work arrangements can have a huge impact on a couple’s ability to better balance domestic and work commitments.

Adopting these changes should start at the top. As we heard from one executive of a major retail firm in Australia, “The CEO’s attitude really matters. Our CEO works flexibly all the time. We help him make this transparent to staff, so they don’t assume they need to be in the office 24-7 to support him while he’s working elsewhere.”

Second, and even more important, male leaders need to explicitly support everyone on their team who chooses to work this way. For example, they should set clear boundaries about when people will or will not be available, transparently communicate their teams’ schedules to clients, and make sure that no one on the team disparages people using flexible-work models.

Our data shows that these attitudes are already taking hold among men under age 40. Such men are more likely to be part of a dual-income household, to contribute to child care (and thus to seek flexible-work options), and—critically—to change their behavior to support women at work, particularly with regard to flexible-work policies. For example, they are more likely than older men to say that they would change the schedule for routine meetings to accommodate people who work flexibly.

Model the right behaviors. Men should be mindful of the work environment they create and the messages they send, and they should take steps to model the right behaviors. For example, before a predominantly male team books an off-site event at a traditionally male-oriented venue, such as a golf course or a cigar bar, all the team members should be asked about their preferences for location. Many women would love a day on the golf course, but it’s worth checking. Notably, this goes both ways—teams that are predominantly female should find out all the team members’ preferences for location before, say, holding an event at a traditionally female-oriented venue, such as a spa.

Men should be mindful of the work environment they create.

Similarly, male employees should avoid making any assumptions about female employees, including their goals, needs, and ambition levels. For example, a male manager’s well-intentioned move to “help” a new mother by taking her out of contention for an international job assignment may instead end up adversely affecting her career. (Besides, nobody is likely to do the same for a new father.) Instead, the manager should simply ask the employee whether she wants to be considered for such a position—and if so, should actively support her to make it work. The evidence shows that women are just as ambitious and eager to take on leadership roles as men, and that the culture in which they work determines whether they stay at an organization.

Crucially, men should also speak up whenever anyone behaves inappropriately, whether through comments to colleagues, in client interactions, or in any other way that reinforces a negative, retrograde corporate culture. When leaders don’t take action in those situations, they are sending an implicit signal that such behavior is OK.

Communicate fairly. The stereotypical male communication style is to dominate discussions and fill the room, whereas many talented employees—particularly women—have equally strong ideas and contributions but are less dominant in the way they present them. The most effective communicators are able to employ a variety of styles and tailor their approach to the situation, and male leaders should recognize and support all styles.

For example, in meetings, male leaders should ensure that everybody has sufficient opportunities to speak, that nobody is talked over or consistently interrupted, and that credit goes to the originator of a good point and not just whoever talked the longest or the loudest. (See “ How We Closed the Gap Between Men’s and Women’s Retention Rates ,” BCG article, June 2017).

Similarly, when giving feedback, male leaders should focus on actions rather than personality traits. Research from Catalyst, a nonprofit that promotes inclusive workplaces, indicates that when providing feedback—for example, during a formal performance evaluation—many managers use words such as “abrasive” or “helpful.” But giving specific feedback about actions taken and outcomes achieved is much more effective. For example, rather than describing an employee as “helpful,” highlight a specific action: “Focusing the discussion in our weekly meetings on projected results was helpful in aiding us to hit our target for the quarter.”

When giving feedback, male leaders should focus on actions rather than personality traits.

Sponsor a high-potential woman. Increasingly, companies are launching programs in which a senior male leader sponsors the career of a junior woman in his department or business unit. Sponsorship is a far more structured form of support than mentorship, which typically involves occasional conversations and informal career advice. Sponsorship entails advocating for a female employee at key inflection points in her career, such as bringing her to high-profile meetings, supporting her application for a promotion or a key international post, and ensuring that she gets the training and development she needs to move up in the company.

Get involved with company-specific initiatives. Many companies are launching internal programs dedicated to improving the recruiting, retention, and promotion of women. Men should actively take part in these programs by, for example, serving on a diversity and inclusion committee, attending a conference on the topic (whether internal or external), or using social media to create greater awareness. (Many companies have social media groups and channels that are closed to the public, spurring more candid discussions among employees and executives.) A CEO who shows up to attend an internal affiliation event or conference, for instance, can help signal the importance of the topic more than any number of press releases or emails.

Data clearly shows that gender diversity leads to better operational and financial performance. Achieving that kind of success can happen if the entire organization takes part—specifically, if men get off the sidelines, join with women, and become actively involved in creating an equitable workplace.