Gender diversity has become a top agenda item for companies, and, it turns out, women have some allies they might not have expected: millennial men. Our research shows that the attitudes of young male employees regarding gender diversity are closely aligned with those of women. Compared with older men, they are more likely to be part of a dual-income household, to contribute to childcare (and thus want childcare and paid parental leave programs), and—critically—to adapt their behaviors in support of their female coworkers.

Women@BCG Podcast

Millennial men make up a critical constituency, and companies should engage them in shaping family policies and to improve gender diversity.

Listen to Partner and Managing Director Michael Tan and Women@BCG Fellow Katie Abouzahr as they discuss the changes to the workplace that millennial men will bring, and the five ways companies can prepare to attract and retain top talent and improve the workplace for everyone.

Those are the key findings of our analysis of survey data from more than 17,500 respondents at companies in 21 countries. Women represent an immense talent pool, yet they commonly encounter significant workplace challenges. For women who have struggled with these difficulties, the results of our analysis should be heartening. And for leadership teams, the findings have clear implications. Gender diversity is not a women’s issue. Young male employees are highly attuned to the issue as well. These young men comprise a large component of the workforce, so companies can differentiate themselves by taking steps to create truly balanced teams. (See the sidebar, “Implications for Leaders.”)

Implication for Leaders

Our analysis points to the following implications for company leaders:

- Workplaces are at a turning point, and a company’s diversity strategy for business success is now more important than ever.

- There has been a big shift in generational mindsets. Millennial men’s attitudes toward gender diversity are more progressive than those of older men. Like earlier generations, millennials have attitudes that were shaped by their experiences growing up and the family roles they expect to take on.

- More than simply saying the “right” things, these young men are willing to change their behaviors to support greater gender diversity.

- Accordingly, the young men in this group make up a critical constituency, and companies should engage them in shaping family policies and supporting women’s issues.

- Companies that engage young men in helping to break the glass ceiling will not only build a stronger culture and improve their operational and financial performance, they will also differentiate themselves in the recruiting marketplace and develop a richer pipeline of talent.

We have discussed some of these steps in previous publications. (See, for example, Getting the Most From Your Diversity Dollars , BCG report, June 2017.) By understanding young male employees’ perceptions of diversity, companies can get ahead of the issue, making themselves more attractive to recruits of both genders, increasing retention of female employees, and creating a truly balanced workforce.

Societal Shifts Take Root

Why are the attitudes of young men toward gender diversity different from those of older men? One possible explanation is that when they were growing up, their experiences—and role models—were vastly different from those of previous generations. According to a 2014 study by Working Mother, US millennials of both genders are more likely to have grown up with two working parents. Nearly half (46%) said that their mother had returned to work before they were three years old, compared with only a quarter of baby boomers. Moreover, millennials were more likely to see earning parity between their parents. In the US, almost half said that their mother earned the same as or more than their father, compared with just 16% of baby boomers. And as gender issues become part of the conversation in markets worldwide, even young men who didn’t grow up in a dual-income household are highly likely to understand the issues that women face at work.

In our research, we surveyed employees and company leaders about the problems that women face, along with their perceptions of 39 corrective gender diversity measures that companies can take. There were roughly equal numbers of male and female respondents, who represented a wide range of ages and family structures. We compared the responses of men younger than 40, including millennials, who were born after 1983, and “Xennials,” born between 1977 and 1983.

The results show that men younger than 40 are far more attuned than older men to the obstacles that women face in the workplace. Not only are younger men more aware of the obstacles overall, but they are also more aligned with women on the challenges that women perceive as critical. Among men under 40, 26% cited retention as a major barrier for women, compared with 15% of men 40 and older. (Among women respondents of all ages, 36% cited retention as a barrier.) In some markets, the differences between younger and older men were even more pronounced. For example, in the US, Australia, and the Middle East, younger men were more than twice as likely to cite retention as a problem.

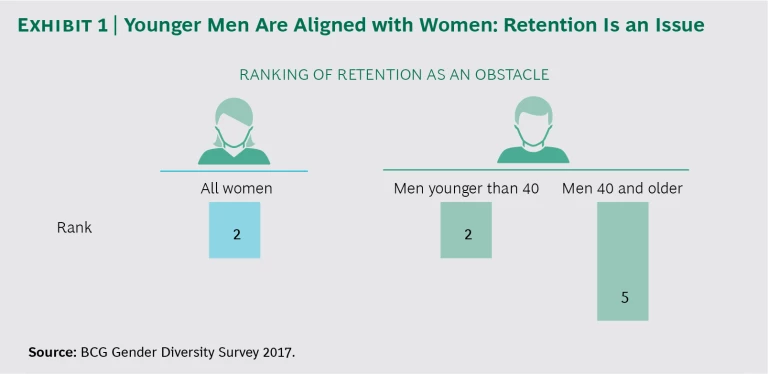

When asked to rank the relative importance of different obstacles, both women and younger men cited retention as the second-biggest factor, whereas older men ranked it fifth of five factors. (See Exhibit 1.) To be clear, however, we should point out that younger men were more in line with older men—and less in sync with women—on some of the other obstacles.

When asked to identify which of the ten highest-priority gender diversity initiatives their companies should implement next, men under 40 and all women ranked work-life balance measures such as flexible work as the top priority. By contrast, older men ranked leadership transparency and commitment highest.

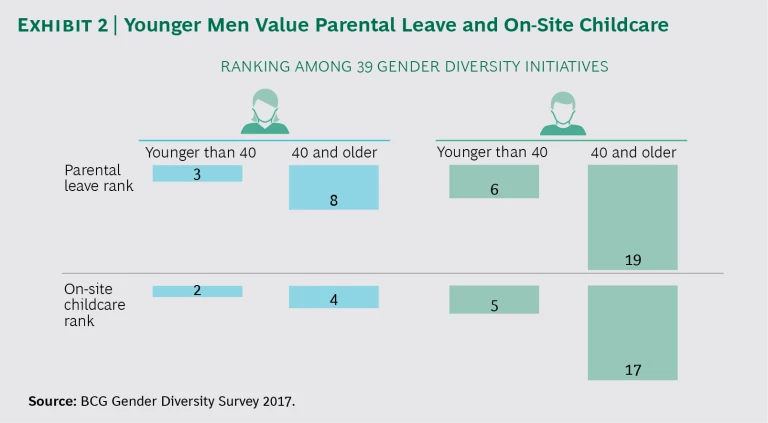

Finally, when we looked at the full list of 39 interventions and asked about the most important, we found that men under 40 were much closer to women in their ranking of the interventions overall than they were to older men. In two areas, men under 40 were the furthest from their older male colleagues: parental leave and on-site childcare. For both interventions, men under 40 rated these much higher than did older men (a difference of ten places in the rankings), and younger men were much more in line with the ratings of women of all ages. (See Exhibit 2.) Notably, fatherhood had little impact: the rankings of childless men younger than 40 were just as similar to women’s rankings as those of their male counterparts who had children.

This may indicate that even if they are not themselves parents—and thus do not currently benefit from parental leave or on-site childcare—younger male respondents have a different perspective of what life might entail should they eventually have children and that they expect to be more involved. One respondent wrote, “Many young men increasingly want to take on a 50-50 split in responsibilities with their partner, take six months of parental leave, or work part-time, but they often find there’s a lack of support [at companies]. The focus can seem to be just on women and flexibility.”

Younger Men Are Willing to Change Their Behaviors

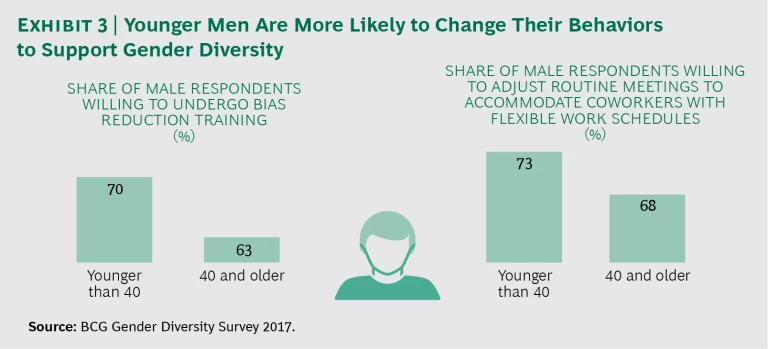

The data shows that in addition to being closer than older men to women in their ranking of the interventions, younger men are more likely to change their behavior to make the interventions succeed. Specifically, a higher percentage of men under 40 said that they would take steps to support flexible work, such as changing the schedule for routine meetings, redistributing work across a team, and tracking performance on the basis of outcomes rather than hours worked. Additionally, younger men indicated that they are more willing to hire candidates from nontraditional recruiting pools and to undergo bias reduction training in order to improve gender diversity. (See Exhibit 3.)

Looking to the Future

The findings of our analysis point to clear priorities for company leaders.

Get men involved in diversity programs. There is persuasive evidence that the most successful gender diversity programs are those that involve men’s participation. (See “ Five Ways Men Can Improve Gender Diversity at Work ,” BCG article, October 2017.) Companies can get men involved by appointing them to diversity programs, setting up sponsorship programs in which senior men advocate for high-potential women, and encouraging men to take advantage of flexible work programs. Those who hold senior positions and work under flexible terms should be celebrated as role models.

Make sure that each of the company’s flexible work policies covers both men and women. Parental leave should be consistently available to employees of both genders. (See Why Paid Family Leave Is Good for Business , BCG report, February 2017.) The same holds true of flexible work programs; they should not be identified—even informally—as programs that are for the mothers of young children. As one respondent said, “I feel like some flexibility programs within the company are advertised for everyone but actually meant only for women.” Indeed, among the executives we interviewed in the US, 55% said that millennials of both genders clearly want flexibility and that their companies are subject to increasing pressure to accommodate this need.

Consider creating a program or support network specifically for employees with children. Because working parents have particular needs, the company should consolidate its resources for them and offer them opportunities to connect with one another. One male respondent told us, “As a father of two young children, I often feel like I’m facing a lot of challenges similar to women colleagues who have kids. I think a young-parent program would be beneficial for both women and men in that life stage.”

Focus the business case for diversity on men aged 40 and older. The older men are the middle and senior managers who shape the day-to-day experience of women, and if they don’t buy into the concept of gender diversity, it will not succeed. Moreover, the causes behind women’s stepping off the career track are often not explicit discrimination but rather an accumulation of daily hassles. (See “ Dispelling the Myths of the Gender ‘Ambition Gap ,’” BCG article, April 2017.) To improve the situation, senior men need to understand the importance of retention and advancement and also that many of the organizations that claim to be gender neutral are nowhere close. As we heard from one executive-level respondent, “Good talent gets promoted [at this company]. No question.” But the data suggests otherwise: women at his own company rated advancement as the second-largest obstacle to gender diversity.

Once these measures are in place, include them prominently in your recruiting strategy. The demand for gender diversity programs is already strong among younger generations, and it will grow even stronger over time. The forward-thinking companies that put these measures in place will begin to generate performance improvements immediately. In addition, they can double down on those gains by using their diversity programs to differentiate themselves, make themselves more attractive to recruits, and build up a strong pipeline of committed employees for the future.

Achieving gender diversity is both a challenge and an opportunity for organizations, and success requires everyone’s involvement. According to our analysis, young men are highly attuned to gender issues and aligned with women on the underlying root causes and relative effectiveness of specific company initiatives. In this way, they are a hidden resource. Smart leaders will capitalize on this, giving their companies a recruiting advantage, creating more equitable workplaces, and ultimately generating better company performance.