Over the past several decades, US companies have made major investments aimed at improving gender diversity in the workforce. By some measures, those investments have paid off. Forty years ago, just half of US women aged 25 to 54 participated in the workforce. By 2014, that number had increased to 75%, according to the Council of Economic Advisers. Yet for the vast majority of these women, middle management remains the end of the road.

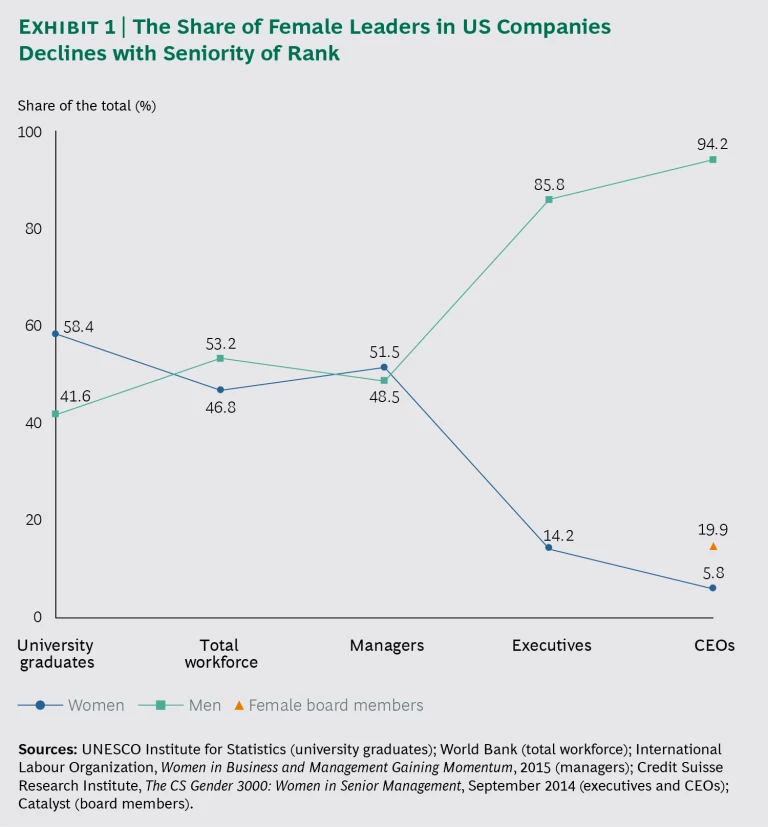

The data is stark: among the CEOs of the 2015 S&P 1500, there were more men named John than there were women. Catalyst, a nonprofit that tracks inclusion in the workforce, found that women currently fill just 19.9% of board seats of companies on the Fortune 500 and a mere 5.8% of CEO spots of companies in the S&P 500. (See Exhibit 1.) Among executive boards, over the past four years, the US has seen only 2% growth in the number of women, compared with 11% growth in Western Europe, according to Egon Zehnder, an executive search firm.

It isn’t for lack of effort: most CEOs know that gender-diverse teams lead to better performance. For example, a 2016 Peterson Institute for International Economics study of some 22,000 global companies found that as companies increased the number of female board members, their profit margins increased by 15%.

And it isn’t for lack of ambition among women: on the basis of earlier BCG research, we know that when women enter the workforce, they are inherently just as ambitious as men. (See “Dispelling the Myths of the Gender ‘Ambition Gap,’” BCG article, April 2017.)

In fact, the real problem is that many organizations simply don’t know which measures are most effective in improving gender diversity. Companies invest money to launch programs, but they aren’t diligent about tracking results. So they have no real understanding of the payoff they’re getting on those investments.

To understand the landscape of gender diversity, we recently interviewed senior executives and surveyed men and women at large US companies. (See the sidebar “Our Methodology.”) In the aggregate, the results are sobering: 89% said that their company has a gender diversity program in place, yet only 27% said that they have actually benefited from it. By that yardstick, much of the money, executive bandwidth, and time that companies spend on these programs is being wasted.

OUR METHODOLOGY

Drilling down one level, we also looked at the relative effectiveness of specific measures such as mentoring, flexible work, and support from senior leaders. The results give CEOs a quantitative case for what they can do to improve their gender diversity programs: they can drop measures that may not be working and reallocate resources to other measures that deliver a bigger payoff.

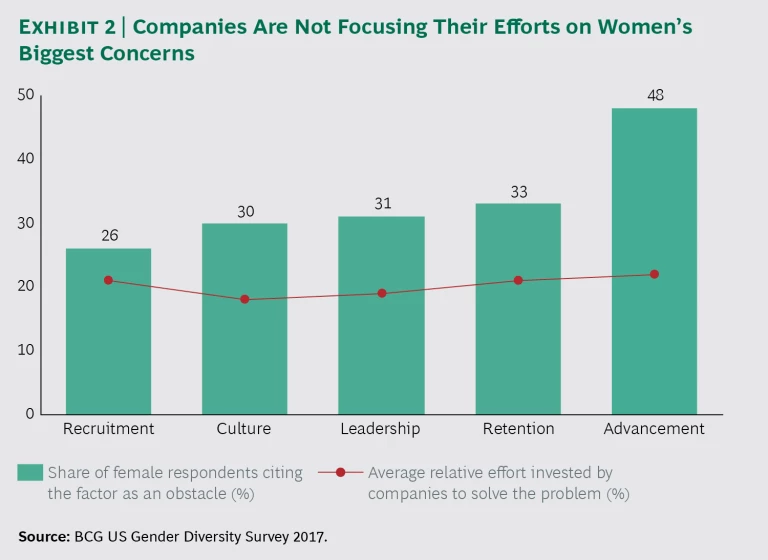

A Mismatch in Perceptions

A key finding of our research is that there is a mismatch between the perceptions of women and those of senior leaders—who are overwhelmingly male at most organizations—regarding the main challenges to achieving gender diversity. Women cited obstacles to advancement as the main source of slow progress, followed by retention. But fewer than 25% of male senior leaders agreed. (And among male respondents at all levels, only 15% of men see either retention or advancement as an issue.) Instead, male leaders typically cited recruiting as the biggest challenge, with 35% saying that it was an obstacle. By contrast, women ranked recruiting as the least important issue; fewer than 26% agreed that it was a challenge.

Leaders may overrate recruitment because it seems to be a problem that is easily solved: companies can measure the percentage of women among new hires and make quick adjustments. Yet it’s much harder to ensure that those women succeed over the long term. According to Catalyst, among US investment banks, for example, 31% of junior and midlevel managers are now women. Yet in that same group of companies, only 16% of senior positions are filled by women.

Unless companies also address retention and advancement, female recruits will either leave or end up stuck in middle management. (For a case study on how a company improved the gender balance of its executive team, see the sidebar “General Mills Triples the Number of Women in Leadership.”)

GENERAL MILLS TRIPLES THE NUMBER OF WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP

Nearly ten years ago, General Mills launched a set of enterprise-wide efforts to increase gender diversity in its senior ranks. Having taken early action across a range of initiatives, General Mills is now well on its way to building a balanced C-suite. Top initiatives include the following:

- The CEO has expressed a strong public commitment to gender diversity, holding regular meetings with senior leaders—including a chief diversity officer—to discuss diversity metrics and gauge progress.

- The company has revamped its recruitment processes. Steps include maintaining diverse lists of candidates, adjusting job descriptions to attract the best candidates, training managers to spot unconscious biases in hiring, and mining succession pipelines for employees with leadership potential.

- Cognizant of millennials’ increasing demand for greater workplace freedom, General Mills now offers flexible work arrangements, as well as competitive paid family leave and benefits for both male and female employees.

- The corporate culture now plays a key role in the employee selection process. Candidates are screened to ensure a good cultural fit and confirm their willingness to support the company’s diversity agenda. The CEO’s strong commitment and middle management’s buy-in help shape the company’s inclusive corporate culture.

- Recognizing the importance of female role models for aspirational leadership, General Mills supports networking through mentoring circles—low-cost, highly effective sessions that deliver a substantial return while allowing women to benefit from the professional support and guidance of senior staff.

This series of coordinated interventions has enabled General Mills to boost the share of women in senior leadership positions from 9% in 2013 to 33% in 2016. In addition, women now hold 51% of middle management positions.

The misperceptions matter. When leaders don’t have a clear idea of a problem, they simply aren’t able to solve it. Our research shows that companies are significantly underinvesting in advancement. In fact, they are spreading their investments more or less evenly across all major categories of concern. (See Exhibit 2.)

Three Categories of Interventions

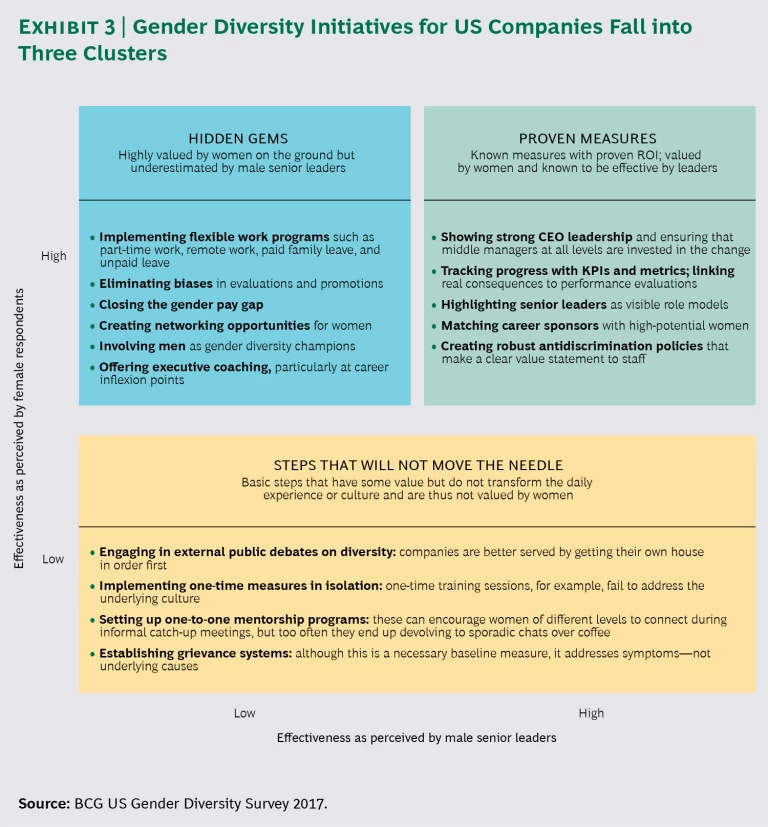

By ranking gender diversity initiatives according to their relative effectiveness among women and among senior leaders, we have segmented them into three categories: hidden gems, proven measures, and steps that will not move the needle. (See Exhibit 3.)

Hidden Gems

Our research identified a set of initiatives that many organizations underestimate. Even though women value these measures and cite them as effective, senior leaders—particularly men—do not think that they work and do not rank them as high as do women. Why? In some cases, male leaders may think that it is too difficult to implement such initiatives effectively, or they genuinely do not see thebenefits that the measures could bring. In particular, these interventions tend to be those that improve both retention and advancement, and thus they address the fundamental obstacles that women encounter and leaders fail to recognize. In that way, they offer clear opportunities for companies to create meaningful change.

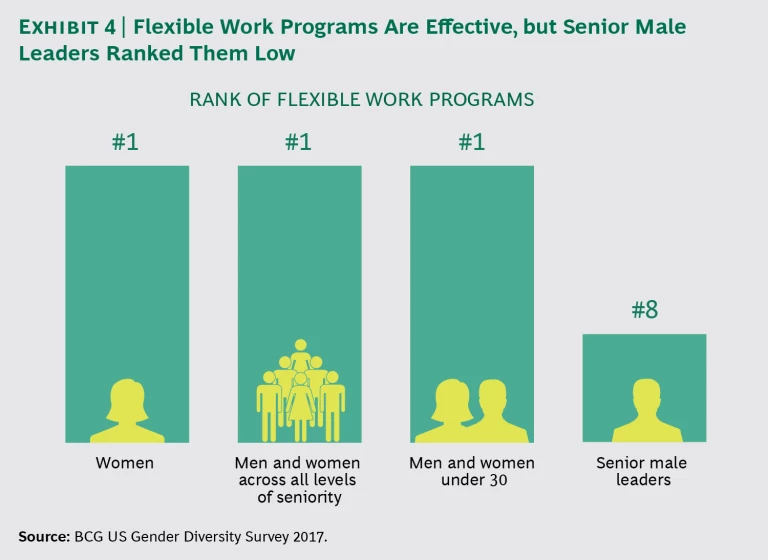

Implementing Flexible Work Programs. Flexible work—including part-time positions, paid family leave, working remotely, and additional or unpaid vacation—was the top-ranked initiative among the group we studied. More than half of all respondents, and 59% of women, cited it as the single most effective gender diversity intervention. Yet only 34% of senior male leaders agreed with them. Senior male leaders ranked flexible work programs number eight. (See Exhibit 4.)

Regarding family leave, the US is one of just eight countries—and the only member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—with no national paid-leave policy. This is a significant gap that affects women’s careers. According to a study by the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, women who are offered and accept paid maternity leave are 93% more likely than women who take no leave to be in the workforce 9 to 12 months after giving birth. (See Why Paid Family Leave Is Good Business, BCG report, February 2017.) In this way, flexible work is crucial for overcoming retention issues and increasing the number of women who reach middle management, thus creating a viable pipeline of leaders who can advance up the rungs of the organizational ladder.

The demand for flexible work programs is likely to grow. Among both men and women younger than 30, flexible working was the top-ranked intervention. Among the executives we interviewed, 55% told us that male as well as female millennials clearly want flexibility and that their companies are under increasing pressure to accommodate these employees.

It’s noteworthy that according to our data, more senior male leaders worldwide than male leaders in the US support flexible work, making the US an outlier. Considering that most multinational companies recruit in the global marketplace, US CEOs would do well to reduce this gap.

Eliminating Biases in Evaluations and Promotions. Flexible work programs can help retain talent, but eradicating any inherent biases in the system is key to ensuring that women can advance to the C-suite. US company leaders may argue that they operate in a genuine meritocracy, but research by Catalyst and other organizations suggests otherwise. Most managers and executives are subject to unconscious biases that affect how they hire, evaluate, and promote people. Identifying these biases and systematically eliminating them will go a long way to creating a more balanced workforce. For example, by removing any identifying personal information, companies can create gender-blind shortlists for internal promotions and give each candidate a truly fair shot. Companies can also make key decisions that are based more on hard data and less on subjective, qualitative elements, such as comments on a candidate’s personality or personal circumstances.

Closing the Gender Pay Gap. It’s somewhat astonishing that in 2017, female employees in the US are still paid measurably less than men for the same work. Although this is a chronic issue, companies can use data and structured steps to address it. For example, they can conduct company-wide reviews to ensure that people in equivalent roles are on the same pay scales, and they can eliminate salary negotiations, which research by Catalyst suggests can disproportionately benefit men and perpetuate pay disparities. Ultimately, taking intentional, corrective action is the surest way to ensure that all employees will be paid fairly for their work.

Creating Networking Opportunities for Women. Companies should also consider actively supporting networking forums—for example, employee resource groups—for women. Such groups enable women to connect on a wide scale, particularly when they are significantly outnumbered at an organization—such as an industrial or engineering company—or work in far-flung locations. Networking forums can facilitate women’s coming together, sharing experiences, and identifying role models whom they might not otherwise encounter. When done well, networking forums create a strong sense of affiliation and improve retention of women in middle management.

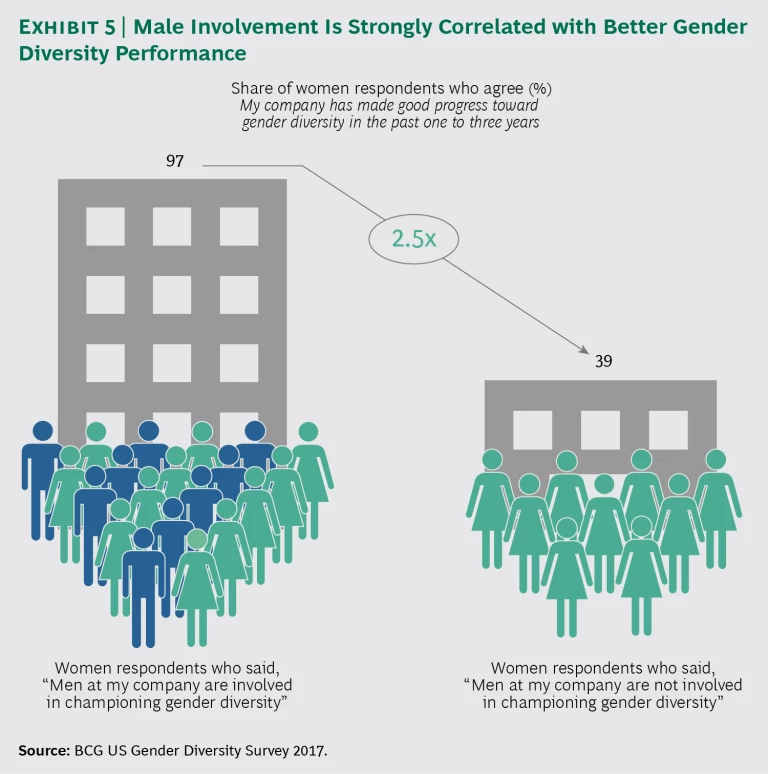

Involving Men as Gender Diversity Champions. The data on this point is incontrovertible: the more that men are involved in a gender diversity program, the more progress the company makes. (See Exhibit 5.) Men dominate the leadership teams at most companies, and if they don’t buy in, nothing will change. Men should sponsor women and support their progress to leadership positions, be called out as visible role models, be clearly seen to take advantage of key policies such as parental leave, and play a role in diversity initiatives. Regardless of how men are involved, the message is clear: men’s participation is correlated with better gender diversity performance.

Offering Executive Coaching. Women value executive coaching, particularly at key inflection points in their careers—for instance, immediately following a promotion or role change—to develop new skill sets quickly and help build confidence so that they can hit the ground running. Such relatively small investments can put women on a stronger career trajectory and set them up for future leadership, ultimately yielding a high return. Furthermore, these investments send a clear signal to high-performing women that the company values them, increasing their confidence in themselves and convincing them that they are able to take on more ambitious career goals.

Proven Measures

All companies should be aware of the interventions that have a clear ROI. Female employees as well as senior leaders deem these proven measures effective. They can create meaningful, sustainable changes in an organization.

Showing Strong CEO Leadership and Having Middle Management at All Levels Invested in the Change. Among the executives we interviewed, a staggering 73% cited CEO leadership as one of the top priorities for improving gender diversity. It is crucial also for middle management to be invested in the change. Our research found that middle managers tend to be more resistant: on average, they are 5 percentage points less willing to change their behaviors to further gender diversity than are senior managers. Yet middle managers have a far more direct impact on the day-to-day experience of female employees. If middle managers do not support gender diversity, it simply will not happen, no matter what the CEO says. (See Untapped Reserves: Promoting Gender Balance in Oil and Gas, BCG and World Petroleum Council, July 2017.)

Tracking Progress with KPIs and Metrics and Linking Real Consequences to Performance Evaluations. Companies need to carefully select meaningful diversity metrics to gauge their progress. Even better, linking progress on these metrics to performance evaluations helps give real teeth to diversity efforts. We offer, however, a note of caution: metrics that become quotas regarding the number of women at the company or in a particular role can be polarizing, and the employees and leaders we surveyed considered them to be among the most controversial interventions. We heard from executives who said that they believe that quotas had played a significant role in creating a step change in diversity, but the survey data indicated that awareness of their use was low and that they were often overlooked.

Highlighting Senior Leaders as Visible Role Models. A second proven measure is making sure that the company has senior people who can serve as visible role models to women at lower levels. Role models can help women see a clear, feasible path to the C-suite. Notably, senior men—for example, male leaders who have climbed to the top while balancing significant nonwork responsibilities or men who are part of a dual-career household and are seen to juggle family life and work effectively—can be just as inspiring as senior women.

Matching Career Sponsors with High-Potential Women. Sponsorship programs—in which the company identifies promising women and matches them with senior leaders who can advocate for their promotions, team assignments, and training and development—generate results. And the absence of such programs can hurt. The executive of a consumer packaged goods (CPG) company told us, “Our data on women was strong on hiring, pay equality, and performance ratings.” But a failure to spot and nurture female employees with leadership potential, he said, “resulted in a lower promotion rate for women…and impacted turnover among midlevel managers.” To achieve meaningful gains, sponsorship requires strong and systematic processes involving sponsors who are willing to go the extra mile—and stick their necks out—to ensure that talented women advance through the organization.

Creating Robust Antidiscrimination Policies That Make a Clear Value Statement to Staff. Many companies treat antidiscrimination policies as boilerplate drafted by the legal department and HR to meet the minimum standards for compliance. Worse, some companies blatantly ignore these policies. Antidiscrimination policies may seem like baseline measures, but establishing them provides company leaders the opportunity to take a public stand and clearly signal their commitment to gender diversity. Companies that go beyond the basics, drafting a strong and clear message—and then educating their employees on the policy and what it means—can revamp their culture.

Steps That Will Not Move the Needle

Not all diversity interventions have equal impact, and our data clearly identified some that neither transform the culture nor have the support of female employees. These are measures that may in theory have merit, but they can sap resources and attention from other, more effective measures while doing little that creates real change. Several types of intervention fall into this category.

Engaging in External Public Debates on Diversity. Some companies try to position themselves as models in the area of diversity, for example, by participating in discussions at external conferences focusing on women in leadership. Women in our survey said that they do not perceive this as effective; most companies would be better served by getting their own houses in order.

Implementing One-Time Measures. It is extremely easy to launch isolated meas-ures—one-time bias training, for example—or to issue edicts describing the new way company employees are expected to work. But in companies that fail to sustain efforts over time or to establish robust policies that change the underlying culture, such isolated, one-time measures are doomed. Worse, they erode management’s credibility.

Setting Up One-to-One Mentorship Programs. Mentorship is less formal than sponsorship (discussed above). It typically involves a senior executive and a junior female employee having periodic one-to-one meetings that generally focus on career advice. Mentorship can be helpful in some cases, but most companies struggle to create good mentoring relationships on a large scale. All too often, these programs end up devolving to sporadic chats that simply lack the gravity and substance that can make a serious difference in the day-to-day experience of most working women.

Establishing Grievance Systems. Grievance systems are necessary for baseline measurement, but, in most cases, they address the symptoms of an unsupportive corporate culture, rather than the underlying causes.

The Right Business Case

Successful implementation of these initiatives hinges on a clear business case. The results of our research suggest that the case for change should be tailored to the particular circumstances and needs of each industry, subindustry, and organization. For example, for CPG companies, there’s a clear customer advantage to promoting women to senior ranks. Women make 85% of all consumer purchases, according to Bloomberg. “CPG is a destination industry for women,” one executive at a global CPG company told us.

For companies in other industries, including, for example, technology, the value proposition is rooted in winning the war for the best talent. Because labor markets emphasize the value of knowledge workers, top talent is a technology company’s primary asset. A company that limits its leadership talent pool to 50% of the population is at a competitive disadvantage. (For a case study, see the sidebar “Making a Case for Change at Vistra Energy.”)

Making a Case for Change at Vistra Energy

In male-dominated industries such as utilities, many companies find it difficult to promote women into leadership positions. Vistra Energy, a Texas-based electric utility that worked to build a bulletproof case for change, relied on a few key strategies, including the following:

- Naming people who understand the benefits of gender diversity to senior leadership positions

- Collecting external data and academic studies that highlight the gains in operational and financial performance of companies that have balanced leadership teams

- Using internal data—such as performance metrics—that links employee productivity to business outcomes

- Sharing such supportive data points with key employees to champion greater gender diversity

- Training and educating managers to understand diversity’s impact on team performance

The result: Vistra Energy hired the first women to its senior leadership team in 2013. Four years later, the company’s leadership team is 62% female.

The US has a long and storied history of fighting for women’s rights, particularly in the workplace. World-class organizations, many of which participated in our study, have made significant strides in recruiting and hiring women. Yet they are now at a critical juncture. Ultimately, US companies must make the conscious choice to shatter the glass ceiling.

The journey is long, but for those willing to make a concerted effort, sustainable gender diversity can become a reality. Rewards await, including significant financial gains. Ultimately, increasing women’s share of leadership at the top is not only the right thing to do—it’s a smart business strategy.