If you want to change employees’ behavior, give them a nudge. If you want that change to spread quickly, go digital.

Nudges are a key tenet of behavioral economics, a field that combines psychology and economics to understand and direct the process by which people make decisions. Deployed appropriately, nudges can steer people to make better choices. Digital technologies boost nudges’ scale and speed, making them a valuable tool for change management in organizations of any size. Today’s fast-paced changes in the workplace and in the nature of work—trends that are examined in the New New Way of Working Series—require companies to positively influence the behavior of thousands of employees of all types. (See Twelve Forces That Will Radically Change How Organizations Work , BCG Focus, March 2017.) Thoughtfully designed, well-tailored digital nudges can help.

Digital nudges use familiar online technologies such as SMS text messages, email, push notifications, mobile apps, and gamification to encourage people to take desired actions. In addition to being relatively simple and inexpensive, tech-based nudges can feed off socially acceptable group behaviors and spread quickly throughout an organization to induce people to think or act differently. Digital nudges also produce data that organizations can analyze to gauge the success of their efforts, allowing them to learn and recalibrate as they go.

Digital nudges can be an effective part of an organization’s broader change programs, as all organizational change is built on getting people to consistently act or react in a different way, even when no one is watching. Organizations can use digital nudges to adapt to changing economic conditions, new technologies, globalization, and competition. (See Getting Smart About Change Management , BCG Focus, January 2017.) Leaders get the best results when they pick specific behaviors they want to change, determine which have high priority, test nudge campaigns in small segments of the organization, and then scale up what works.

Behavioral Economics and Nudges

Behavioral economists use the term nudge to describe a prompt that can lead people to adopt a new behavior. Popularized by recent books such as Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein; Thinking Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman; and Michael Lewis’s latest, The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds, nudges are easy, low-cost interventions that can alter people’s decision making without attaching a substantial financial reward or penalty to the process.

Digital nudges take advantage of the ubiquity of mobile devices and online communications to speed the adoption of new behaviors. But for digital nudges to work, not any old text message will do. Successful nudges take into account employees’ tendencies to act and think automatically, reach people when they’re open to making a change, and connect to small steps that aren’t difficult to take. Tech-based nudges can be customized to appear when they’re needed, with a context and pace that work for the individual.

Successful nudges also take into account accepted group norms, and they correspond to a series of concrete milestones, recognizing the satisfaction people get from checking off items on a to-do list. Examples of digital nudges: a personalized email that reminds someone to complete an enrollment form; a text from one team member to the rest of the group that shares the work goals the sender met that week and spurs the recipients to meet their goals.

Tech-based nudges don’t need to be expensive. A personal email “thank you” from the boss for a job well done or a happy-face emoji on a WhatsApp group chat costs nothing but scores big. Workers at an Israeli semiconductor manufacturer were given the option of receiving a $30 bonus, a pizza voucher, or a complimentary text message from the boss as an incentive to meet targets, writes Dan Ariely in his 2016 book, Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations. On the first day, free pizza produced the biggest uptick in productivity, but by the end of a week, the SMS compliment was the most powerful motivator, according to Ariely, a Duke University professor of psychology and behavioral economics.

Use of behavioral economics and digital nudges in the public sector has outpaced use in the private sector. Government agencies in the UK, the US, Australia, and elsewhere have used digital nudges for nearly a decade to coax people into taking actions, such as paying taxes on time, becoming organ donors, or staying current on student loan payments. More for-profit enterprises and nongovernmental organizations are now following suit, adopting nudges to help employees be more productive, improve customer service, and take other beneficial actions that they might not have otherwise.

Results from nascent experiments with digital nudges are incomplete, but in the real world nudges can produce real results, so we expect digital nudges to do the same. (See “Virgin Atlantic Uses Nudges to Help Pilots Reduce Fuel Consumption.”)

Virgin Atlantic Uses Nudges to Help Pilots Reduce Fuel Consumption

Organizations can use nudges to coax employees to comply with desired behaviors, which can directly benefit the bottom line. Virgin Atlantic Airways discovered this when it used nudges to help pilots cut fuel consumption.

Airlines are famously low-margin businesses, and fuel is a major and highly variable expense, accounting for approximately one-third of operating costs, according to a 2016 academic research report on Virgin Airlines’ nudge experiment.1 Despite knowing they should try to minimize fuel use to reduce costs and carbon dioxide emissions, pilots didn’t always act accordingly.

The airline tested a series of nudges to see which would change pilots’ behavior—335 of its pilots were randomly assigned to one of four groups, including a control group that received a letter stating that fuel use was being monitored as part of a study. Other groups got one or more interventions, including a personalized report detailing how much fuel the pilot used that month, a fuel use goal that they were encouraged to meet, and an offer of a small donation to charity for reducing fuel consumption.

Ultimately, all four nudges caused pilots to reduce fuel use while taxiing, flying, and landing. Even the letter that merely reminded pilots that their behavior was being observed changed their fuel use. Virgin Atlantic estimates that as a result of the study, which covered eight months and 40,000 flights, pilots cut fuel costs by $5.37 million and reduced carbon dioxide emissions by more than 21,500 metric tons—all because of some well-conceived nudges.

“This experience highlighted the power of fairly simple, low-cost nudges to produce positive behaviors,” said Philip Maher, Virgin Atlantic executive vice president, operations. “It also demonstrated the importance of experimentation to determine what works and what doesn’t in our organization.”

1. Greer K. Gosnell, John A. List, and Robert Metcalfe, “A New Approach to an Age-Old Problem: Solving Externalities by Incenting Workers Directly,” National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2016.

Because nudges are a relatively new way to think about motivating people to change behaviors, many leaders might not be familiar with the social science on which they’re based. Organizations frequently design policies and programs under the assumption that people think rationally before they act. But behavioral economics shows that the processes people follow to make decisions are more complex.

Research suggests that people are strongly influenced by the context in which they’re operating when they face the need to decide on a new course of action, often without noticing it. The influences can include emotions, biases, how other people think or feel, and the accepted behaviors within a particular group, such as an office or a company. Behavioral economics research has also shown that people default to the status quo but, with the right type of prompting, can be encouraged to adopt new behaviors.

Lessons to Nudge By

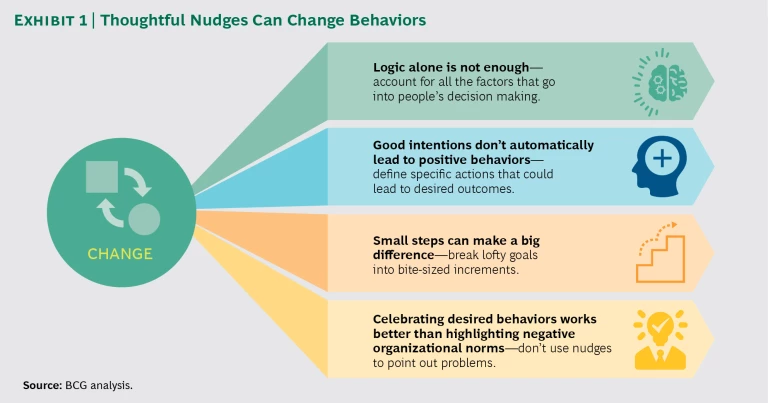

From our work with leading organizations, and within BCG itself, we have distilled several lessons for leaders who want to harness the persuasive power of digital nudges to create new behaviors. (See Exhibit 1.)

Logic alone is not enough. To persuade people to act or react differently, you need to consider the context in which they approach problem solving, the biases they bring to a situation, and how they interact or cooperate within a group. You also need to reach them at a time when they’re open to hearing the message and in a way that works for them. One digital nudge that appeals to people’s emotions uses a reward and recognition app that is part of an enterprise’s internal social network or employee message board. A boss or coworker can use the app to award a salesperson a digital smiley face, sticker, or badge for closing a new deal, for example, or to send a note saying “Great job!” Such recognitions appeal to people’s desire to be appreciated in an authentic way, and they work best when they call out a specific behavior and a clear business result.

Good intentions don’t automatically lead to positive behaviors. What people say and what they do aren’t always the same. Ask people if they want to save more for retirement or share more feedback with coworkers, and odds are they’ll say yes. But then life happens, and they don’t follow through. There’s a scientific reason for the gap. Research has shown that people are generally overconfident about their abilities, and as a result they underestimate how difficult it will be to change their behavior. This tendency is evident in corporate mergers that fail because the newly joined businesses are overly optimistic about the degree to which they can change their respective cultures to be more efficient as a single entity. You also see it in work settings when employees leave a corporate training session excited about what they’ve learned but return to their daily routines without incorporating any of their new knowledge.

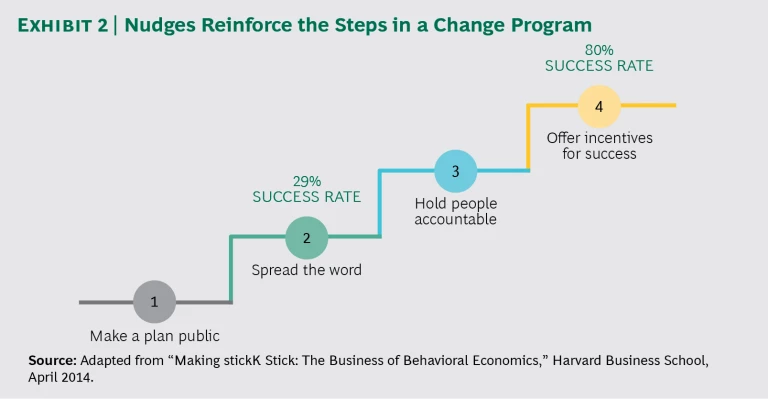

To turn good intentions into real results, define specific actions that could lead to a desired outcome and then design nudges that lead people to take those actions. Nudges can be reinforcing mechanisms that act at select points along a ladder of success. (See Exhibit 2.) Nudges can be tied to making a plan public, spreading the word about it through workplace communication channels, holding people accountable by asking them to check in with someone else when they’ve reached designated milestones, and offering meaningful incentives for achieving the goal. According to research reported in a Harvard Business School publication, change efforts that incorporate the first two steps succeed close to 30% of the time, while programs that include all four have an 80% success

A division of a major multinational energy company used digital nudges and peer influence as reinforcing mechanisms to encourage top executives to practice the training they’d received to become more connected with the organization’s workforce, part of a larger effort to respond faster to changing economic conditions. Executives were asked to set small, weekly goals toward improving their leadership, engagement, and communication skills. As part of that effort, the executives committed to using instant messages and a WhatsApp group message thread for weekly check-ins to share what they had accomplished. A text reminder from the change management team was the only nudge that 40% to 50% of the executives needed to complete the weekly check-in. The rest followed suit after seeing texts from peers who had already completed their tasks.

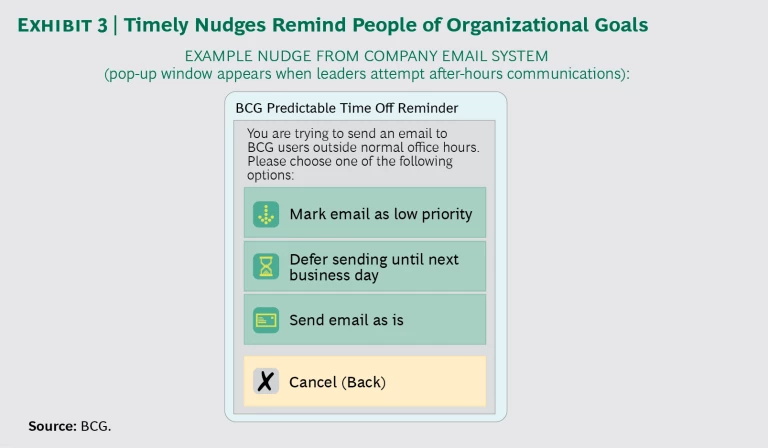

Small steps can make a big difference. People overestimate their ability to change by failing to translate lofty goals into the incremental steps they need to take to get started. Digital nudges can be tied to those smaller commitments. BCG created such a digital nudge as part of an internal directive to be more considerate of employees’ life outside of work, an initiative known as PTO. (See “ Making Time Off Predictable—and Required ,” Harvard Business Review, October 2009.) The firm recognized that BCG leaders have to reinforce the desired culture through their own behavior. It created a macro in the company email application that causes a pop-up window to appear whenever leaders attempt to send a message after hours. (See Exhibit 3.)

The nudge appears at the exact moment leaders need a reminder that the action they’re taking may not align with what the company expects of a considerate team player. In keeping with the nature of good nudges, it doesn’t block their ability to send the message. Nudges shouldn’t take away someone’s ability to choose; they should simply make the desired behavior easier or more compelling at the moment of decision.

Celebrating desired behaviors works better than highlighting negative organizational norms. When attempting to change behaviors, organizations can sometimes unintentionally emphasize an accepted, negative practice, which can promulgate the undesired behavior. An organization in which managers and employees consistently turn in performance reviews late may want to change that behavior, but it may unwittingly reinforce the behavior by circulating memos that emphasize the volume of outstanding reviews. By pointing out the problem, the company is broadcasting the fact that the standard for reviews is to be late. A nudge that instead calls out the desired behavior could help turn things around. The organization could circulate a weekly email or text message praising managers and employees who have submitted performance review paperwork on time.

Getting Started with Digital Nudges

Nudges won’t work in a vacuum. Organizations can’t use them effectively without doing some necessary background work, including cultivating open communication about the issues that need to be changed and experimenting to see what works.

Understand why employees will or will not use nudges. To use digital nudges as part of change management, leaders must be comfortable with asking employees to behave in different, specific ways and with designing, testing, and scaling nudges that help employees do so. Leaders also need to be comfortable trying new ways of doing things.

Pinpoint the behaviors that need to be changed. Identify and prioritize areas that need improvement, and then create the steps needed to help people make the desired changes. For nudges to work, goals and steps must be as specific as possible. “Be better at collaborating” doesn’t cut it. Goals such as “Invite a representative from the procurement department to all supply chain meetings” or “Complete 25 outbound telemarketing sales calls per shift” are better because they’re specific and unambiguous.

Pick a nudge and test it. Try a digital nudge for a specific goal with one group, office, or business unit. A pilot can be a short, low-cost experiment. Monitor individuals’ progress and use the data analytics built into applications and other digital technologies to gather information on results. Study what works to see how you can replicate it in a larger nudge campaign.

A government agency tested several types of digital nudges to increase staff analysts’ use of an online library. Employees received one of four types of email nudges: alerts about the library, alerts offering anecdotes about coworkers who used the library and were praised by leaders as a result, alerts that chided people into using the resource, or alerts offering one of two incentives—a small one of inexpensive chocolates or a large one of an expensive pen—for using the site and recommending it to coworkers.

Tests showed that getting a digital nudge significantly improved how often and how long employees used the resource library. Brief email alerts about the library worked best, and personnel responded better to the more expensive incentive than to the small one—insights that would have been unavailable without the experiment. The agency used results to run additional tests, but in the short term, library use increased, which improved staff productivity by hundreds of hours a week.

Make people accountable. Because people care about what others think, tie nudges to some form of third-party accountability. That doesn’t mean making people check in with their boss. It could be having employees pair up as goal buddies and commit to regular check-ins to see what progress they’re making toward the goal. Or, use a group email, text, or mobile application to post results on a digital leaderboard that everyone can see.

Learn from successes and failures to roll out a larger digital nudge program. Some pilot projects might fail—and that’s okay. Failure is an important part of experimentation, and committing to digital nudges means accepting the possibility that a particular nudge won’t work. When digital nudge prototypes don’t produce a change in performance, use the failure as a conversation starter. What does it tell you about your organization? Can you tweak the nudge to make it more successful?

Nudges, based on principles of behavioral economics, are small, low-cost, timely interventions that can help people think and act differently. For digital nudges to work, they should reflect the context in which people make decisions. To effectively change behaviors, divide nudge efforts into discrete steps, make sure they dovetail with accepted group behaviors, and hold people accountable. Digital nudge campaigns need buy-in from leaders, clear goals, and an initial small-scale test before rollout.