Two months into its formal merger, company A’s integration teams were bickering with corporate over cost-cutting targets—targets set several months earlier, several layers up. Many other untested top-down assumptions had been made that were not grounded in reality. It was no surprise when, at the six-month mark, the integration began to falter.

Company B’s integration experience was starkly different. By the six-month mark, four of the five newly constituted business units were not only beginning to realize savings, they were also enjoying an uptick in revenues despite an industry slowdown. In fact, these units actually exceeded a number of synergy targets established during the deal.

What explains the contrast between the two companies?

In a nutshell, company B followed a disciplined, pragmatic approach to pursuing merger synergies, from identifying and validating them to creating detailed plans with built-in accountability. Unlike company A, it not only advised integration leaders on how to aim high, but also gave the managers responsible for achieving the targets a say in the target-setting process. When a team missed a milestone or experienced a shortfall, company B had the visibility it needed to troubleshoot and course-correct promptly.

Acquirers like these have demonstrated that it is possible to deliver promised synergies consistently and systematically. As a result, they do more than augment total shareholder value. Markets “buy” their synergy story early in the deal and factor it into the share price. And markets reward these companies later, once they’ve proved that they can deliver on their promises, by showing confidence in their future corporate deals.

Making Synergies Happen

Although achieving synergies—whether streamlined costs, procurement efficiencies, or heftier revenues—is the fundamental rationale for M&A, many mergers fail to deliver them. If they don’t fall short of the targets, they may take too long to hit them, which amounts to the same thing: diminished returns, disappointment for shareholders, and depressed value. Alternatively, the desired synergies may come at too high a cost: literally, because of overspending, or figuratively, in the form of declining morale or loss of talent. Indeed, for all these reasons, the market often takes a jaded view of corporate marriages, expecting them to destroy value.

In our work guiding and analyzing hundreds of post-merger integration (PMI) projects, we’ve learned what works and what doesn’t in delivering synergies—whether the synergies involve ongoing reductions in overhead, procurement, or other operating costs, or augmentation of revenues through the newly acquired customer base, new capabilities, jointly developed new products, or better price realization.

In virtually every successful case, leaders pursue synergies with speed, rigor, and pragmatism, doing as much analysis, planning, preparation, and fine-tuning as possible before the close. Then, even as they carry out the PMI, they are well on the way to realizing value. They also use a high-engagement, rapid-iteration approach that achieves two imperatives for ultimate synergy success: validating stretch targets effectively and ensuring a high level of line accountability. We’ve distilled these broad characteristics into six essential ways that enable companies to capture synergies.

1. Tightly Link Due Diligence and PMI

Often there’s an unintended divide between the due diligence team and the integration planning team. Acting under immense time pressure, the due diligence team must quickly formulate a set of assumptions about potential synergies. Generally, its members have only a limited understanding of the levers that drive the synergies and the challenges involved in achieving them. That can lead to overly optimistic estimates. But estimates can also tilt conservatively, because no acquirer wants to overpay or disappoint shareholders later on.

Stated synergies are thus broad-brush and often imprecise. It’s not uncommon for the due diligence team’s scenarios to unearth 20% or more in cost savings based on assumptions about consolidation, or to estimate more than 10% in additional revenues based on industry benchmarks or high-level assumptions about market or customer segment share. Such estimates, however, take into account neither the operating models of the two separate companies and of the newly combined entity nor the differences or overlaps in customer bases.

Management and bankers, eager to make the deal happen, don’t always look critically at the trajectory of the core business or the size of the stated synergies. And at this point, the business unit heads who will be responsible for delivering on those targets typically have no say about their feasibility or time frames. So when integration begins, they question where the numbers came from. Whatever the case, estimates at this stage cannot be clinically precise.

Recognizing these realities, successful companies ensure a well-coordinated handoff from the due diligence team to the integration planning team. Some even place M&A team members who were involved in the due diligence on the PMI team assigned to develop the bottom-up estimates of the same numbers. Linking due diligence and PMI also allows for a greater degree of ownership and accountability on the part of line managers. Finally, linking the two processes enables more aggressive stretch targets, as we’ll explain later.

It also makes sense to involve the business unit heads—those charged with implementing the plans—in target setting at the due diligence stage. And including a member of the due diligence team on the integration management office’s (IMO’s) baseline and synergies platform team can help ensure continuity and accountability.

It’s equally important to deconstruct and articulate the drivers of the savings at a high level. This will help establish synergy targets and ranges that make later refinements possible, once more information becomes available to teams. These targets and ranges will also give teams the ability to evaluate potential gains from the new company’s operating model as more information emerges during the integration phase.

Consider the actions of the business unit of a €40 billion-plus Europe-based multinational industrial corporation when it acquired another company’s business unit. Both acquirer and target were in the same business and had overlapping products. During due diligence, the acquiring company crafted a detailed synergy plan. It also made its functional managers—the head of sales, the head of HR, and others (all of whom would later be on the integration team)—part of the due diligence team. Their role in due diligence was to help assess synergies, function by function. Ultimately, they would have to sign off on their targets. The due diligence team began assessing the main potential synergies and defined the key levers with which to achieve them. Even before they had the numbers, they had established a disciplined process.

Although this approach meant that more people were involved in due diligence, the result made it worthwhile: the functional managers knew what to expect later, which motivated them to uphold their commitments—in other words, to ensure that the targets would stick.

A first version of target metrics was actually created in the due diligence process, with targets broken down by functional area, year, and location. Although the targets continued to be refined after signing, the company was already well positioned to jump-start the PMI process with aggressive, yet realistic, synergy estimates.

2. Make the Most of Clean Teams

Because of the restrictions on sharing sensitive information prior to regulatory approval or closing, many companies believe they must wait before refining synergy and integration planning. As a result, they can lose precious time and even jeopardize the confidence of their customers. But with the help of clean teams, companies need not fly blind in planning and preparation preclose. In fact, clean teams can be an effective way for companies to accelerate PMI planning.

A clean team is an independent group that, with management’s guidance, collects and analyzes sensitive company data before the close. Established by legal contract, clean teams operate according to protocols agreed on by both companies’ legal departments. Members can be third parties or employees who can be transferred out of the business if the deal collapses, eliminating the risk of compromising confidential information.

Clean teams can be granted access to a wide range of information, such as customer data (including prices, sales volumes, profitability, and marketing plans), supplier data, individual product performance, R&D projects, and specific competitive initiatives. In most cases, a clean team can share aggregated, sanitized results with management. Thus, clean teams allow companies to achieve synergies (particularly procurement savings, R&D savings, and commercial opportunities) faster and assess risks in areas where data cannot yet be legally shared between the companies.

Clean teams thus enable the acquiring company to eliminate blind spots and get a sharper picture of the target company without violating antitrust regulations or confidentiality agreements. So even before the deal closes, companies can accomplish three core integration activities: compiling a wide range of baseline data, such as customer, functional performance, and procurement data; vetting synergy targets; and preparing options for key decisions.

The use of clean teams also helps companies prevent or mitigate common types of merger fallout, such as confusion or missteps triggered by an overlap in client assignments and salespeople. Clean teams’ analyses can help management quickly determine after the closing (or even before) how best to deploy sales teams to avoid such confusion. Managers can see whether overlapping accounts are buying the same or similar products at different prices or terms and determine promptly at close how to resolve such discrepancies, instead of being surprised on day one by a client calling to complain or demand a huge discount.

The uncertainty generated by merger announcements sometimes causes sales to drop; when companies don’t decide on their product offerings or product support until well after the closing, clients often stop buying for months. After the merger of two European machinery companies with many overlapping products was announced, executives noticed that some customers were wary of making buying decisions, concerned that products they relied on might be discontinued. The company formed a clean team to compare the two portfolios and propose products to keep supporting and products to discontinue postmerger. The clean team’s work enabled the company to provide straightforward answers to its customers immediately after the closing, thereby limiting attrition. Without the clean team, management would not have been able to answer customers’ questions accurately until three months afterwards.

3. Establish Stretch Targets

Most leaders involved in mergers don’t fully appreciate the significance of setting stretch targets. As a result, they tend to approach it with inadequate rigor and granularity. By thoughtfully considering stretch targets, leaders engender a

focus on the future—a sense of challenge and creative thinking on the part of integration teams. In effect, they force the teams to stretch their thinking during the planning phase to explore what can be achieved later on, during integration and beyond.

Using the due diligence numbers as a foundation, companies should focus on the high end of the assumptions. By employing creative estimation techniques, they can set more specific, and more aggressive, targets. Specifically, through the process of triangulation, companies can get a closer approximation of targets and see how much of a stretch is reasonable.

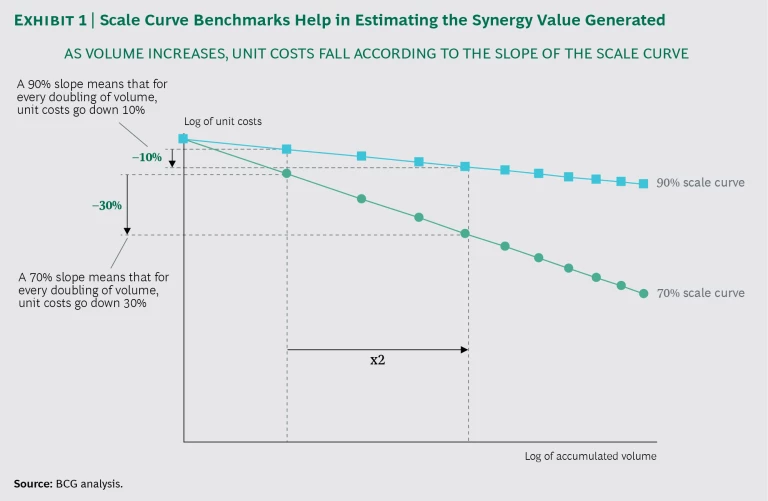

Triangulation entails using multiple data sources, including external information, industry peer data, data from the company’s previous integrations, functional- and business-area experts (such as supply chain and procurement experts), synergy benchmarks, proprietary databases, and scale curves. (See Exhibit 1.) BCG’s proprietary synergy database, for example, provides information by deal size and industry. Through triangulation, companies can narrow their target ranges; then, as they gain access to more data, they can get more granular.

It’s important to document assumptions scrupulously. When managers are operating in the dark about the source of the estimates, it is very difficult to determine how realistic those estimates are and how much they can be extended. And when the numbers are nebulous, people don’t regard stretch targets seriously or with urgency.

Documenting assumptions is also, in effect, a way of rationalizing the opportunities. The more they can be substantiated, the less wiggle room there is for those charged with execution.

4. Rapidly Iterate to Set Targets

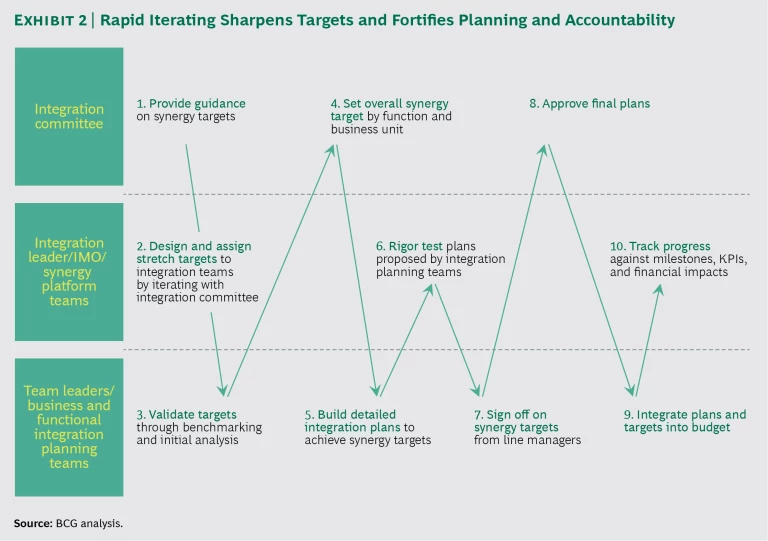

To succeed in reaching targets, we recommend the robust yet practical “W” approach, named for its shape. (See Exhibit 2.) This approach combines rapid, top-down stretch-target-setting with two rounds of bottom-up validation that enable progressively greater degrees of accuracy and detail. It allows companies to stretch to the most ambitious, yet still feasible, extent.

All levels of management with a role in integration are involved in target setting, from the steering committee and integration leader and IMO to the synergy platform teams and integration planning teams within the business units and functional areas. (See the sidebar “Who’s Who on the Integration Team.”) In this way, the process facilitates detailed, actionable planning that supports the refinement and achievement of the high-level targets.

WHO’S WHO ON THE INTEGRATION TEAM

Integration Steering Committee. As the committee that leads the overall integration, the integration steering committee articulates integration goals and principles, sets boundaries, approves processes, makes all critical decisions, and approves final targets and plans. It often includes the CEO and selected direct reports.

Integration Leader. As head of the integration management office, the integration leader heads up and coordinates the integration program. This includes planning; establishing team structures, charters, and processes; offering guidance and support; identifying organizational interdependencies; and setting the agenda for the integration steering committee.

Integration Management Office. With members drawn from across the company, the IMO reports to the integration leader and designs, coordinates, and tracks the overall integration plan, process, and progress. It establishes team structures, charters, processes, and timelines. It also guides, supports, and challenges the integration planning teams and provides quality control for materials that the teams provide to the integration steering committee. Finally, the IMO sets agendas for the executive-level integration committees and escalates issues to the integration steering committee.

Synergy Platform Teams. These teams, part of the IMO, support the business and functional integration teams and ensure alignment. They include the financial baseline and synergies team, talent and organizational design team, communications team, and culture and change management team.

Business and Functional Integration Planning Teams. These teams plan the integration in the business units and functional areas. They analyze synergy opportunities and develop options, recommendations, and plans to support the integration steering committee’s decision making.

Special-Issue Teams. These teams address either critical cross-functional issues or opportunities (such as the customer experience) or specific critical issues (such as customer engagement or decisions from headquarters).

The detail work (bottom-up estimates) is done by those with skin in the game—the people responsible for delivering the results. In addition to rigorously validating targets (before planning teams can go too far down the wrong path), this approach explicitly establishes greater ownership of and accountability for those targets among line leaders.

The W approach offers two other powerful benefits. First, senior leaders can make adjustments when a team comes up short; the bottom-up analysis enables them to see which teams have the latitude to pick up the slack and still allow the organization to achieve its original targets. Second, the approach deters siloed thinking. Companies rarely take a cross-business or multifunctional view of the available synergy opportunities available, but the top-down, bottom-up interactions, along with the IMO’s cross-organizational reach, automatically inject valuable cross-company perspectives.

Consider the approach taken by a major US-based global manufacturer, whose merger promised a whopping $4 billion in announced cost savings—an amount that clearly required across-the-board cuts. Over a period of several months, each business area was required to submit to the IMO increasingly specific synergy target information. First, teams delivered a list of possible synergies, the likelihood of achieving them, the projected order of magnitude of savings, and key assumptions and risks. Next, they provided a revised (and vetted) list with quantified ranges. The final submission showed synergies with their associated costs, both one-time and ongoing. The IMO checked each team’s submissions, in concert with the CFO, who verified whether the targets were on track and supported the company’s strategy. Some targets had to be adjusted or reallocated to other teams.

Because synergies were identified within the context of each unit’s operating model, teams were effectively developing a business plan for each part of the business. This was a big plus, considering that synergies would have to be an integral part of the company’s future operations.

The top-down, bottom-up nature of the approach fostered transparency and alignment throughout the company’s vast managerial ranks and across dozens of business unit, R&D, and finance teams. And because the submissions took place within the normal review process, they served as a sort of business plan review, helping the business leaders stay aligned with the overall planning process.

5. Pursue Revenue Synergies as Diligently as Cost Synergies

When asked how often he sees revenue synergies, a CFO we know replied, “We have no idea. We just tell the line managers, ‘We expect you to build business by X percent.’ The line leaders don’t expect us to track them, as they see it as part of their business.”

Regrettably, this CFO’s response reflects the rule more than the exception. Cost synergies (such as salaries saved as a result of headcount reduction and licensing fees that no longer need to be paid) are easier to account for. But companies plan and track revenue synergies with less rigor and transparency, largely for two reasons: they are harder to track, and leaders view revenue synergies more as part of their day-to-day business than as a distinct exercise.

Integration-related revenue synergies usually get mixed in with the normal revenues of the business, which makes them harder—if not almost impossible—to distinguish. Establishing a baseline thus seems difficult. Many companies fail to evaluate revenue synergies on a regular basis or delay their evaluation to the point that it becomes an afterthought. At other companies, revenue synergies completely escape the attention given to cost synergies—the upfront definition, the execution with clear accountabilities, and the routine monitoring. Either way, leaders are often left asking questions such as these: Did the 10% gain in revenues sought by the merged company come as a result of the improving economy or outstanding performance by the sales team? Or, if sales postmerger declined by 10%, was it because the company didn’t realize synergies? Or were synergies realized, but the business meanwhile fell 30%?

In fact, it is possible to pursue revenue synergies rigorously—with the right approach. In simple terms, revenue synergies are nothing more than the gap between the additional revenues earned as a result of the merger and baseline revenues—those the company would expect to earn had the merger never taken place. They derive from three sources: products and services cross-sold from one company to the customers of the other, new products or services jointly developed by the merged companies, and price and product line optimization.

In deals with revenue synergy potential, management should establish a revenue baseline (the premerger figure) during the integration planning phase. Then, it should ask integration teams to identify revenue synergies as well as concrete initiatives for achieving them. It’s critical for sales leaders to develop initiatives and a sales process that will ensure that synergies are captured in a systematic and disciplined way—by, for example, training on new products and customers, sales lead generation, elimination of overlap in account assignments, and new incentive systems.

Cross-functional teams can develop clear-cut initiatives and roadmaps that, along with the associated KPIs, can be used as a management accounting proxy to deconstruct the source of the new revenues.

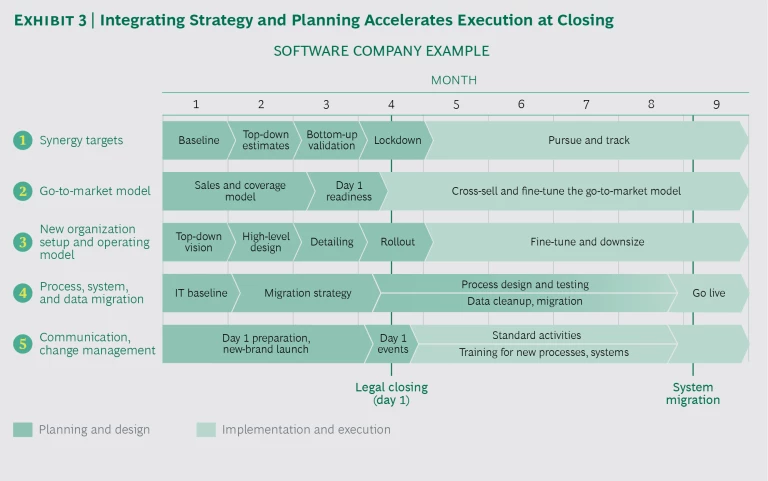

Consider the experience of a leading software company that acquired a $1 billion-plus company in order to cross-sell through a joint go-to-market approach. In just three months—from the deal announcement until the close—the company integrated the target company, resolved major organizational design issues, defined revenue synergies, and developed implementation plans for them. The company was poised to achieve significant year-over-year revenue growth from cross-selling, and the more than $100 million in cost synergies targeted for year one were on track.

How did the company achieve such rapid progress? By focusing ruthlessly on joint commercial opportunities. It quickly developed product offerings and integrated roadmaps to guide their development, while tackling regular integration activities such as organization design, sales force design, and account planning. (See Exhibit 3.)

The go-to-market model was launched right at the close, with a joint sales kickoff and intensive training. To motivate the sales organization, the company put in place an incentive program for the first year that rewarded salespeople for selling the acquired company’s software to the expanded client pool. In short, the new company was ready—and fired up—to cross-sell on day one.

6. Track Performance Throughout the PMI

As the well-worn adage cautions, “If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Among the most common PMI oversights is the failure to systematically monitor synergies. As a result, leaders don’t have a clear view of their progress, and companies typically don’t aim for the greatest possible “stretch” in their targets. Without a formal, structured process, it is also difficult to coordinate interdependencies, which play a vital role in achieving synergies.

When they see they are hitting their targets, companies know not only that the merger is succeeding but that their assumptions were on point. Leaders and managers can now fine-tune or deliberately shift direction with a clearer sense of the outcome. Success is shared (because those responsible for hitting the targets had a say in setting them), so teams are motivated to stretch further. True integration is taking root. Finally (and not least), performance tracking gives companies a way to communicate postmerger progress objectively to the market—a move, BCG has shown, that yields tangible benefits. (See the sidebar “The Value of Keeping Investors in the Know.”)

THE VALUE OF KEEPING INVESTORS IN THE KNOW

BCG recently conducted a study of 286 acquisitions in North America carried out between 2010 and 2015. We found that the value of the combined companies was around 6% higher for companies that disclosed their synergies than for comparable companies that did not. Moreover, investors bid down the shares of companies that did not announce synergies.

Certainly, the mere act of announcing projected synergies doesn’t guarantee higher valuations. But companies that are disciplined about pursuing and executing synergies—to the point of disclosing them—enjoy a share price premium. (For more on the study, see “The Real Deal on M&A, Synergies, and Value,” BCG article, November 2016.)

The integration plan serves as the basis for tracking progress on synergies. The IMO works with the integration teams to create roadmaps and milestones for each integration project, determine synergy timing by project, map interdependencies and risks, and develop KPIs to ensure steady progress. The two groups also work together to verify the plan’s rigor. Tracking revenue synergies involves measuring not only the revenues generated from the synergies but also the underlying initiatives (and component actions) needed to reach the targets (which is actually easier).

To get a full picture of synergy progress, companies must also carefully and systematically consider integration costs—the expenses and one-time (capital) costs associated with each synergy that are required to carry out the merger. A company might have to spend up to $1.50 to realize $1 of synergy, but it will pay that amount just once, while the synergies payoff happens every year. Still, such costs can quickly eat up synergy gains (and drain short-term cash flows), so companies must ensure that the underlying initiatives not only make sense but also yield a positive return on investment. Costs can be tracked by project within the integration plan.

Once they are finalized (before or at the closing), the integration projects should be locked in to create “one version of the truth” to track against. Plans and initiatives should then be entered into an implementation tracking system so that the company has a central information repository with which to maintain that one version. The tracking system helps teams respond promptly to missed milestones, future risks, or performance shortfalls and make the necessary adjustments before they escalate. Leaders can identify the potential impacts of delays, intervening before anything gets derailed or critical interdependencies are put at risk.

All synergies and integration costs should be monitored on a monthly basis for the first 24 months (to allow for swift recovery if a project veers off track); quarterly tracking is sufficient thereafter. Tracking should continue until the last dollar of synergies is captured. Both synergies and integration costs should be tracked against the plan by project, using a different set of metrics to monitor realized synergy value, headcount changes, and one-time costs. Tracking should include a formal reconciliation process between the project view and finance or controlling view.

The merger of two major US retailers illustrates powerfully the effect that tracking can have on achieving—or even exceeding—synergy targets. During due diligence, the two companies figured that their merger would save them from $300 million to $500 million in costs. In fact, the new company realized $740 million in savings—more than double the original base estimate. In large part, this success was attributable to a meticulous and disciplined execution plan, which included detailed roadmaps for the new company’s more than 100 synergy-related initiatives.

The use of clean teams before the close helped as well. These teams analyzed such critical metrics as the cost of goods sold and were able to do preliminary planning, category by category and vendor by vendor. Immediately after the closing, the company was ready to home in on stretch targets to streamline every key area: corporate overhead, cost of goods sold, procurement, even the sales and marketing teams.

Many mergers fail because companies don’t pursue synergies in a rigorous, disciplined way. Often, companies are not nearly ambitious enough in setting their synergy targets, and they overlook the importance of speed in achieving them. Many companies mistakenly assume that until the close, their access to information is too limited for target-setting and planning purposes. They end up incurring unnecessary delays that can not only undermine synergy achievement but also impede integration and even put customer relationships at risk.

With the right approach, companies can buck the odds. By adhering to the six essentials described here, they can aim higher, achieve more, and realize cost and revenue synergies more swiftly—thereby realizing the true promise of integration. And for their discipline, investors will reward them.