Private equity firms have set their sights on a new wave of software companies hitting the buyout market. Although investments in such companies have the potential to generate high returns, success is far from assured. PE firms just getting into the game must rapidly “crack the code” of software deals in order to capture the outsize returns enjoyed by many

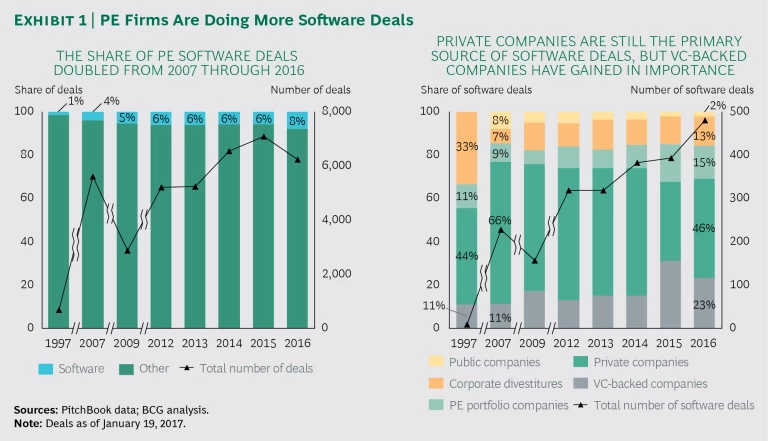

Like other investors, PE firms have been attracted to software companies by the potential for profitable growth and high valuation multiples. (See “Software’s Favorable Economics Attract Investors.”) As a share of their total number of investments, PE firms’ investments in software companies increased from 4% in 2007 to 8% in 2016. The number of annual acquisitions more than doubled, from 228 in 2007 to 481 in 2016.

SOFTWARE’S FAVORABLE ECONOMICS ATTRACT INVESTORS

The market for software is large and growing. Revenues in 2016 totaled $154 billion for enterprise software and $178 billion for infrastructure and systems software, according to Gartner’s estimates. For both types of software, Gartner forecasts that the rate of revenue growth will continue to outpace that of many other industries. The market for enterprise software is forecast to have a CAGR of 9% from 2016 through 2020, growing across all segments. The market for infrastructure and system software is forecast to grow at a slightly lower rate, with a CAGR of 6%. Several attributes promote software companies’ favorable economics:

- Software products are highly scalable and have low deployment and upgrade costs.

- Either of two prevalent business models—an annual subscription fee or a license with a recurring maintenance fee—offers an opportunity for recurring revenue.

- The churn rate under both models is typically in the low single digits, especially for enterprise software. Because software is deeply integrated into business processes and systems, significant effort and investments are required to switch providers.

These attributes lead to high and predictable gross margins compared with those of many other industries. The largest publicly listed software companies have gross margins of 70% to 85%, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margins of 20% to 25%, and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) margins of 25% to 33%. The inherently favorable economics promote higher enterprise value (EV) for software companies. For the largest software companies, EV/EBIT multiples are 12 to 22 (median of 13), and EV/EBITDA multiples are 15 to 32 (median of 19).

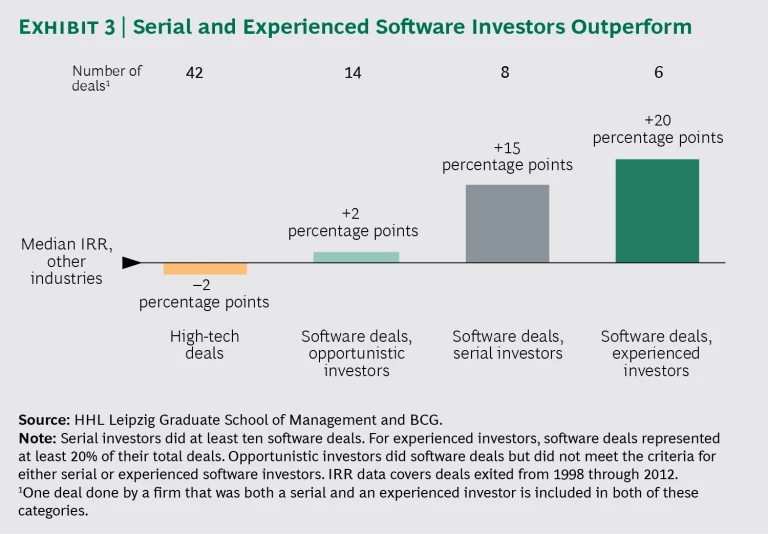

Returns from software acquisitions have generally outperformed the market. However, an analysis conducted by BCG found that expertise in software deals makes a tremendous difference. In the sample we studied, serial software investors (those that had made at least ten software deals) outperformed the median IRR of other industries (excluding high tech) by 15 percentage points; experienced investors (whose software deals represented at least 20% of their total deals) outperformed by 20 percentage points. In contrast, opportunistic (neither serial nor experienced) investors outperformed by only 2 percentage points.

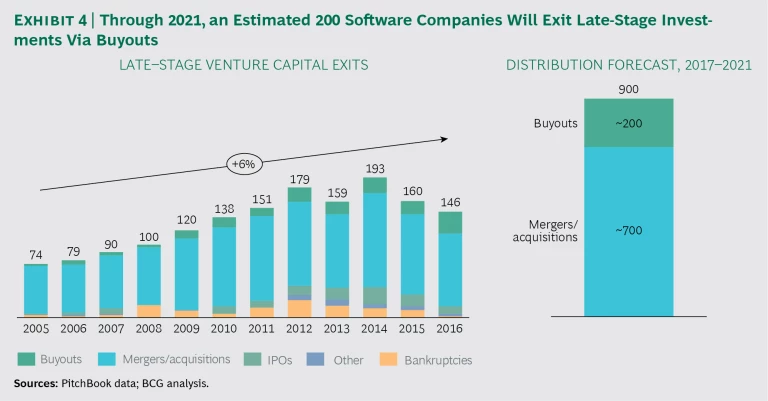

What sets the serial and experienced investors apart is their ability to successfully apply a distinct set of value creation levers to generate higher returns from their software investments. The importance of knowing which levers to apply is especially relevant given that a growing wave of software companies, funded by venture capital (VC) investors, is expected to reach the market during the next five years. We estimate that VC firms will exit their late-stage investments in more than 900 software companies, with PE firms acquiring approximately 200 of them.

To capitalize on the opportunity, new and previously opportunistic investors must quickly build or acquire the capabilities needed to identify the best software company targets and apply a set of industry-agnostic and software-specific value creation levers.

The Evolving Market for Software Deals

In an era of rising PE investments, software deals stand out as an area of increasing activity. (See Exhibit 1.) The total number of PE deals increased from approximately 5,600 in 2007 to approximately 6,200 in 2016. As noted above, the number of software deals at entry increased from 228 to 481 during this period, with their share of total deals doubling from 4% in 2007 to 8% in 2016. The number of software deals exited rose from 96 in 2007 to 182 in 2016, representing an increase from 4% to 5% of the total deals.

We expect a sharp increase in software deal exits, in terms of both the absolute number and the share of deals, over the course of the next five years. The median holding period for investments decreased from 5.3 years in 2012 to 4.2 years in 2016, with 50% of investments held for 3 to 6 years. In contrast, the median holding period for PE investments in nonsoftware companies was 5.3 years in 2016, the same as in 2012.

The sources of software deals have changed over time. Private companies are still the primary source, but acquisitions of these companies fell from 66% of all software deals in 2007 to 46% in 2016. During the same period, the importance of PE portfolio companies and corporate divestitures as deal sources increased. Acquisitions of PE portfolio companies (secondary buyouts) increased from 9% to 15% of all software deals, and corporate divestitures increased from 7% to 13%. Investments in public companies decreased from 8% to 2% of all software deals.

We also see a trend of PE firms investing in smaller, VC-backed software companies, as firms recognize the need to gain an early stake in these fast-growing and innovative companies in order to achieve high returns. PE firms have been investing significantly in VC-backed software companies for only the past decade. By 2016, there were 112 such deals across all VC stages, representing 23% of software deals. For instance, in February 2016, CVC Capital Partners closed a $1 billion growth fund that targeted software and technology companies with enterprise values of $50 million to $200 million. KKR & Co.’s first fund dedicated to growth equity investing in technology targeted companies valued at $25 million to $80 million. EQT’s recently closed Ventures fund targeted even smaller equity investments of €1 million to €75 million. At the same time that PE firms are increasingly setting their sights on smaller companies, the valuations of late-stage VC deals are rising, and VC firms such as Insight Ventures are increasingly investing in more and larger late-stage deals. The result has been a convergence in the values of VC and PE investments in software companies.

Add-on acquisitions (in which a PE-owned software company acquires another software company) have been the leading deal type during the past decade, increasing from 47% of all software deals in 2007 to 61% in 2016. The consistently high share of add-on deals reflects the popularity of buy-and-build strategies, as many PE investors seek to form larger software companies.

A shift has also occurred in the exit channels for PE software deals. Initial public offerings are losing favor as an exit route. Investors recognize the significant advantages of remaining a private company, such as the greater freedom to pursue multiyear strategic transformations that may hurt revenues and profits in the short term. The preference for remaining private, combined with an unfavorable market environment for IPOs in recent years, has driven down the number of IPO exits from software companies. There were 13 IPO exits in 2007, compared with 5 in 2016, representing a decline from 14% to 3%. The same period saw a surge in secondary buyouts (in which ownership passes from one PE firm to another). The number of secondary buyouts rose from 22 in 2007 to 79 in 2016, increasing from 23% of exits to 43%.

Serial and Experienced Software Investors Outperform

To understand how investments are performing, BCG and HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management analyzed data for a sample of PE deals from 1997 through 2010. (See “Our Data Set for Analyzing Performance.”) The software deals for which performance data is available outperformed the median IRR of other industries (excluding high tech) by 9 percentage points and the median IRR of high-tech deals by 11 percentage points. Software deals outperformed the mean IRR of other industries (excluding high tech) by 16 percentage points. High-tech deals also outperformed by 16 percentage points, reflecting the exceptionally strong performance of several deals.

OUR DATA SET FOR ANALYZING PERFORMANCE

BCG teamed with HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management to gather and analyze data on a representative sample of PE software deals. We began our joint analysis with a data set of 1,896 PE firms that entered into deals from 1997 through 2010. Focusing on the 875 firms that did three or more deals, we found that 310 invested in software companies. We had IRR data covering deals exited from 1998 through 2012 for 27 of these software investments.

The median enterprise value of the software companies involved in the 27 deals was $37 million. These companies represent multiple regions, with 56% based in the UK, 15% in France, 25% in Western Europe (excluding France and the UK), and 4% in other regions. Although the data set’s geographic distribution generally corresponds to that of fundraising in Europe, it overrepresents the UK market with respect to investments. Similar studies commonly over- or underrepresent countries according to the availability of country-specific data.

In addition to IRR, data for each transaction included attributes that allowed for a variety of analytical perspectives:

- Deal size

- Type of entry and timing

- Type of exit and timing

- Acquired-company attributes (industry, growth rate, home country, and enterprise value)

- PE firm characteristics (fund size and focus and deal experience in software)

- Other relevant attributes, such as industry growth and profitability and the degree of industry concentration

Among software deals, the transaction type with the highest returns was spinoffs of software assets from their parent company, with a mean IRR of 37%. Sales of software companies by founders to third parties had a mean IRR of 30%; for other types of deals (secondary buyouts and taking the company private), the figure was 18%.

The software companies in our sample experienced healthy, albeit not aggressive, growth. Average sales growth was approximately 7% per year during the PE holding period. Average EV/EBITDA multiples of approximately 10 at entry and approximately 13 at exit reflect performance improvements. These multiples are generally lower than those of the largest software companies because the companies in our sample earned lower revenues and thus operated at a smaller scale.

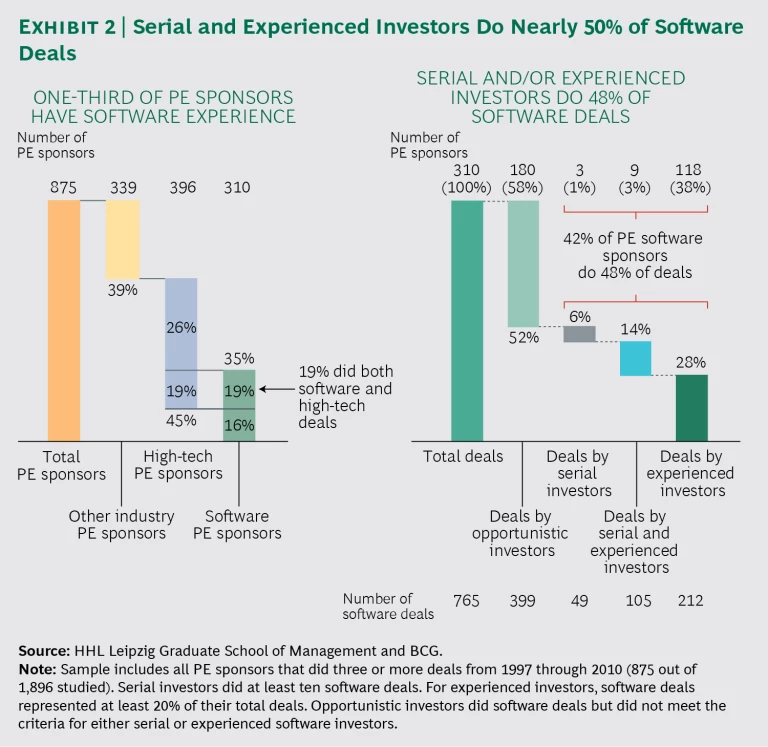

Approximately one-third (35%) of the PE firms in our sample had done at least one software deal. Among these dealmakers, 58% were opportunistic investors, doing 52% of all software deals; 1% were serial investors, doing 6% of deals; 3% were both experienced and serial investors, doing 14% of deals; and 38% were experienced investors, doing 28% of deals. (See Exhibit 2.)

As noted, in software deals for which we have performance data, serial investors outperformed the median IRR of other industries (excluding high tech) by 15 percentage points, experienced investors outperformed by 20 percentage points, and opportunistic investors outperformed by only 2 percentage points. (See Exhibit 3.)

Examples of serial investors include 3i and Carlyle. 3i’s 25 software deals are the highest absolute number in the sample set but represent only 10% of the firm’s total deals; Carlyle’s 18 software deals represent only 14% of its deals. Thoma Bravo is both a serial and an experienced investor: its 14 software deals represent 56% of its total deals. Two firms that specialize exclusively in software deals are Vista Equity (13 deals) and JMI Equity (11 deals).

A Wave of VC-Funded Software Companies Is Hitting the Market

PE firms that understand how to maximize returns from investments in software companies will be well positioned to benefit from the wave of VC-funded software companies hitting the market over the next several years.

The number of software companies entering the late stage of VC investment increased at a CAGR of 8% from 2000 through 2016. In 2016, late-stage VC investments reached a record high of $32 billion. Software companies receiving an initial late-stage VC investment in 2016 totaled 421, compared with 422 in 2015 and a record-high 433 in 2014. As the number of VC-backed software companies has increased, so has their importance as an entry channel for PE firms investing in the software industry. In 2016, 23% of all PE software deals involved VC-backed companies (at any investment stage), up from 11% a decade earlier.

Our analysis shows that these late-stage, VC-backed software companies are now hitting the buyout market. We estimate that, from 2017 through 2021, VC investors will exit approximately 900 late-stage investments through sales to either PE firms or corporate acquirers. Our analysis of the channel distribution indicates that PE firms will acquire approximately 200 of these companies through buyouts. (See Exhibit 4). Additionally, PE firms will continue to invest in early-stage VC-backed companies. It is important to note that only a small share of the software companies hitting the buyout market will be attractive investments. Thorough due diligence will be needed to identify those with high performance in key indicators, such as recurring revenues, customer retention, pricing power, and products that will allow fast scaling of the business.

To forecast the number of late-stage VC-backed software companies that will be offered for sale to PE firms or corporate acquirers, we analyzed historical data from a sample of 4,268 software deals globally from 2000 through 2016. At the end of 2016, 2,552 of the companies involved in these deals were still held by VC investors, 124 had filed for bankruptcy, and 1,592 had exited VC investments through various channels.

We forecast the number of companies entering late-stage VC investments to increase at a CAGR of 7% from 2017 through 2021. This growth rate will be driven by the expansion of the overall software market and an increase in the number of VC firms and corporate VC funds investing in software companies. The current surge in early-stage VC investments in software companies is an indication that more late-stage investments will occur in the medium term.

There has recently been a dip in exits, but we expect their number to revert to the historical trend in the medium term. In 2015 and 2016, late-stage VC exits plateaued at a high level of approximately 150 to 160 per year. We believe this leveling off resulted from two factors. First, because VC investors are pouring more and more money into the sector, software companies do not need to go public or be acquired to fund their growth. Second, these companies’ comparatively high valuation multiples have made them less attractive to some investors. We expect the number of exits from late-stage VC investments to increase rapidly when this peak of valuations starts to decline.

As to the allocation of deals across exit channels, we forecast that buyouts will capture an increasing share of exit deals relative to corporate acquisitions. Buyouts’ share of exits has risen continuously in the past decade, from 5% in 2007 to 22% in 2016, and we believe this upward trend will continue.

Apply Both Industry-Agnostic and Software-Specific Value Creation Levers

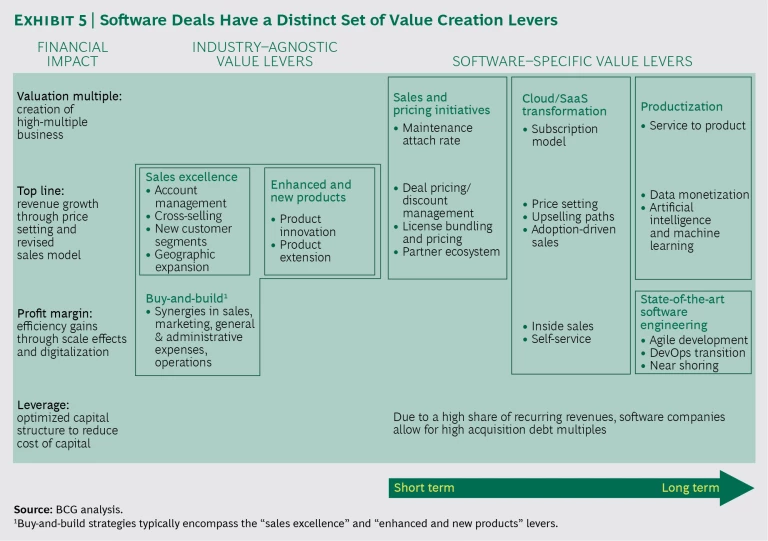

Serial and experienced investors typically apply a rigorous proprietary playbook to create value at software companies, addressing a distinct set of industry-agnostic and software-specific levers. For example, one successful PE investor focuses on strategic acquisitions that accelerate earnings growth, while another emphasizes analyzing and optimizing operations. These value creation levers can be categorized in terms of their impact on the valuation multiple, the top line, profit margins, and leverage. (See Exhibit 5.)

Three industry-agnostic value creation levers are frequently applied at software companies:

- Sales Excellence. Companies increase the “share of wallet” of their current customers through account management, cross-selling, and expansion into new customer segments and regions.

- Enhanced and New Products. To grow revenues, companies can enhance current products by adding new features and improving existing functionalities. They can also expand their offerings by developing new products.

- Buy-and-Build. This lever entails acquiring and integrating several software companies to create a larger player that offers a broader product suite. Such a strategy can accelerate growth into new customer segments and new geographic regions and give the company access to new products. Thus, the buy-and-build lever typically encompasses the “sales excellence” and “enhanced and new products” levers. The larger company that results can also capture synergies related to sales, general and administrative expenses, and operations.

In addition, PE firms that are serial or experienced software investors typically apply four industry-specific value creation levers: sales and pricing initiatives, cloud/software-as-a-service (SaaS) transformation, productization, and state-of-the-art software engineering. Sales and pricing initiatives can be implemented relatively quickly, but the other levers require three to five years, depending on the company’s starting point and organizational complexity.

- Sales and Pricing Initiatives. Improving sales and pricing is the most efficient short-term lever for increasing the valuation multiple and the top line. For example, by bundling maintenance services with products, software companies create a stream of recurring revenues. Those that achieve a high “attach” rate for such services are also typically rewarded with higher multiples. Other pricing initiatives that boost revenue include stringent management of discounts in deal pricing, licensing combinations that address a customer’s distinct needs, and value-based pricing. Effective management of the partnership ecosystem, such as by offering appropriate incentives to motivate sales and providing enablement (such as marketing support) and training to partners, can also promote top-line growth.

- Cloud/SaaS Transformation. Transitioning to a cloud-based SaaS offering typically generates more value than the other levers and is the most fundamental type of transformation. It has two components: the technical shift of software from on-premises deployment to the cloud and the shift from a perpetual-license-plus-maintenance model to a term-based subscription revenue model. The subscription model helps generate a higher valuation multiple by providing a stream of recurring revenues. Improvements to price setting and upselling promote top-line growth. Adoption-driven sales (setting prices and upselling on the basis of a customer’s product usage) also generate higher revenues. Data-

driven inside sales and self-service (the automation of sales via digital channels) promote profit margin improvements. Revenues and profits will initially decline in the transition from a licensing model to a subscription model because the company incurs expenses in reorganizing for cloud operations and delivery, and customers make smaller recurring payments rather than large upfront payments. To avoid being punished by the market, the company must carefully manage the transformation and clearly communicate to investors the steps being taken to create long-term value. - Productization. Standardizing software products and services instead of developing them for the individual customer enables a company to increase scale at a low variable cost and thereby boost profit margins. This approach, known as productization, allows for greater predictability in terms of revenue, cost of revenue, and margins, which in turn helps to promote a higher valuation multiple. In addition, software companies often possess a large base of data from their own products, which provides the opportunity to monetize data as a new source of revenue. The data can be further enhanced with insights generated by the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

- State-of-the-Art Software Engineering. Agile development capabilities relating to both organization design and development processes allow software companies to adjust product features quickly. They also enable companies to increase the frequency of releases while ensuring stable or even higher-quality software. In addition, companies can use the DevOps approach, in which development and operations engineers work together throughout an application’s life cycle to achieve greater speed and higher quality. The automation of testing and quality assurance is essential to achieving these objectives. Finally, companies can increase development capacity at moderate cost by establishing remote teams in “near shore” locations. Leading software companies use these capabilities to increase development efficiency and reduce costs, leading to higher margins.

Imperatives for Success in the Challenging Software Market

PE firms striving to win in the market for software deals must rapidly build expertise in the software industry equivalent to that of serial and experienced investors. First, they must identify the opportunities and prepare to pursue them:

- Understand the opportunities. To identify the most attractive opportunities in the crowded market for software deals, PE firms must understand emerging software business segments, such as SaaS and mobile, and the factors promoting their growth. Because a large share of software companies are headquartered in the US, firms seeking a global perspective on the best companies coming to market also need expertise in evaluating US-based investment opportunities.

- Build sourcing capabilities and a network. In order to gain access to future deals and develop a pipeline, firms must build sourcing capabilities and a network within the software industry and its investor community. Additionally, they must assess which channels will be the best sources. Beyond acquiring software companies from VC investors exiting late-stage investments, firms will have opportunities to make investments through other channels, such as corporate divestitures, leveraged buyouts, and secondary buyouts. To help them assess which software companies are likely to come on the buyout market, BCG has created a database of more than 8,500 late-stage VC-funded and PE-owned software companies. (We used the database to make the forecast shown in Exhibit 4.) Firms can also use the database to identify software companies that match their preferences in terms of region, software sector, and size.

To capture exceptional returns from their software investments, PE firms must then build best-in-class capabilities on several fronts:

- Develop a PE value proposition. To compete against corporate acquirers for attractive opportunities, PE firms need to develop a clear value proposition for software companies. Rather than being absorbed into an acquiring company, a software company acquired by a PE firm remains a standalone entity and has the opportunity to grow if the acquirer pursues a software-specific value creation program or a buy-and-build strategy. The PE firm can also give the software company access to an extensive network of industry experts and a source of funding for future growth. It is critical for PE firms to communicate these benefits, as corporations will continue to pursue acquisitions of software companies in order to complement or accelerate efforts to build software capabilities in-house.

- Build software-specific expertise. PE firms need to build expertise in skills that are unique to the software industry. They also need an in-depth understanding of the software market and the related trends affecting technology and business models. Knowledge at the regional level is especially critical to addressing customer requirements, which differ considerably from place to place. For example, US customers have generally been more open than customers in other countries to trying out and adopting new technology-based solutions, such as mobile and SaaS.

- Put in place the right talent and advisors. Creating value at software companies requires support from a team of seasoned industry experts. To implement software-specific levers, some of which will fundamentally change the company, PE firms need to have the right balance of top internal talent and external support. It is essential to have access to senior advisors, such as former CEOs, with in-depth, firsthand knowledge of the software industry. The team needs experience in scouting out opportunities and operating companies in the hub locations where software companies are concentrated, such as Silicon Valley, the northeastern US, Texas, London, and Israel, as well as a thorough understanding of the customer base in a software company’s core markets.

- Define the software value creation playbook. Firms should use their software expertise to define a playbook for value creation and apply it systematically during due diligence and within portfolio companies. To create the playbook, they must understand the potential impact of each software-specific value creation lever and the time required to implement it. In conducting due diligence, firms can use the framework of levers presented in Exhibit 5 to assess the potential for value creation. After acquiring a software company, firms can work with management to develop a growth strategy and implementation plan for all value creation levers. BCG’s “full-potential plan” supports this effort by combining industry-agnostic levers with software-specific levers. This systematic, disciplined approach enables the company to comprehensively identify all value creation levers for each specific situation. Given the typical holding period of three to six years, some levers need to be applied immediately after an acquisition in order to have impact prior to exit. Outperforming PE firms also ensure that the software company’s management fully supports the value creation initiatives from day one.

PE firms must start preparing now to capitalize on the growing wave of VC-backed and PE-owned software companies hitting the buyout market. Our research shows that PE firms with the most knowledge of the software industry outperform opportunistic investors. Serial and experienced investors have cracked the code of software deals by understanding how to both target the best opportunities and create value at a company once it is part of the portfolio. For PE firms seeking to get into the game and win, the message is clear: gain expertise quickly.