A decade ago, discount grocers had a limited impact in most markets. These players, which primarily offered cheaper prices for a narrower range of products, typically took 10% to 20% of market share around the edges. Today, discounters are evolving from stripped-down, no-frills stores to become a genuine alternative for many consumers—and a major factor in the grocery industry. As a result, they may soon claim up to half of the total share in many markets.

Discounters are opening bigger stores with innovative features, expanding their assortment of fresh and organic products, and selling private-label products that beat out established brands in taste tests—all at much lower prices. Not coincidentally, discounters in many markets are also scoring higher than established companies on customer advocacy, as measured by BCG’s proprietary Brand Advocacy Index (BAI). Their customer base has grown beyond low-income shoppers to include savvy, high-income consumers, who are increasingly asking a fundamental question: “Why should I pay more?”

The dramatic growth of discounters will have profound consequences for the overall grocery industry. Given that discounters are here to stay in many markets, mainstream players need to address the challenge head on by fundamentally transforming themselves to improve their prices, product assortment, and store experience. Some may also opt to launch a discount brand of their own. And discounters must avoid the risks of overexpansion by being judicious about the markets they move into and by ensuring that they can still achieve a structural advantage over current players in those markets.

The Rise of Discounters

Discounters first began to gain traction in the 1990s, particularly in Germany with the Aldi and Lidl brands. The winning formula at the time was to offer low prices on a targeted assortment of mostly private-label products. Stores were cramped and had a low-budget feel, but customers felt they were getting better value—a key differentiator that was sufficient to increase traffic. As a result, discounters managed to disrupt the grocery retail market in multiple countries.

In that initial phase, discount grocers typically performed well during periods when consumer spending was down. These shops were countercyclical, like dollar stores; they benefited from budget-conscious shoppers during recessions. Mainstream retailers, therefore, could afford to ignore the discount grocers and still retain 80% to 90% of the total market.

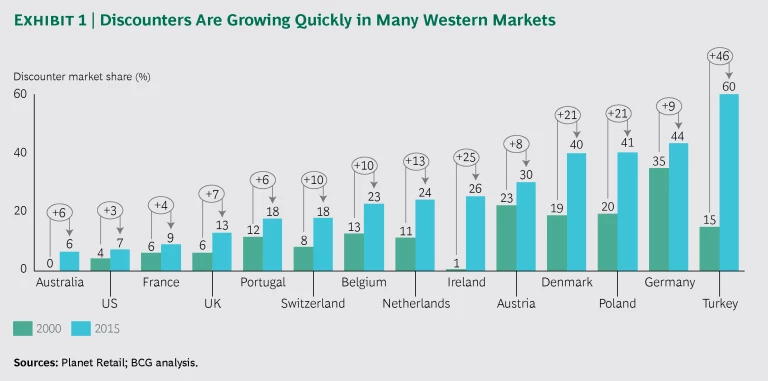

Today, however, that’s no longer true. Discounters grew at a rapid clip from 2000 to 2015, gaining significant market share in many Western countries, including Denmark, Poland, and Turkey. (See Exhibit 1.) That growth shows no signs of slowing, even as household incomes have risen. Worldwide, discounters are projected to increase their number of store locations by 4.4% a year through 2020, compared with just 2.9% for mainstream supermarkets and 1.6% for superstores and hypermarkets. Some regions will see an even faster expansion, including Eastern Europe (more than 30%) and Latin America (approximately 8%).

There is a demographic aspect to that growth: millennials prefer discounters over mainstream grocers in most markets. In large developed markets (including the US, Europe, Australia, Canada, and Japan), this population comprises 275 million people, more than any other demographic segment, and their aggregate spending power rivals that of all other segments combined. Millennials tend to be very pragmatic, opting to buy most of what they need in a convenient location, without the hassle and burden of an overwhelming number of choices. Moreover, they inherently distrust some mainstream brands and are willing to try unconventional options—particularly given the right in-store experience.

Yet the biggest factor in discounters’ success over the past decade is that these companies have evolved and redefined their approach to offer higher-quality products, a broader assortment, and an improved shopping experience.

-

Higher Quality. Discounters have always focused on private-label products at lower prices, but they are increasingly beating out branded products in head-to-head tests. Aldi Süd and Lidl Stiftung were pioneers in this area: their house brand products have won in both blind taste tests and independent quality reviews in Germany since the 1990s. Both companies have further customized their products to meet local taste preferences. More recently, the private-label ketchup from a leading discounter in the UK beat a global brand in a taste test conducted by the Guardian. The two versions have identical ingredients and very similar packaging, yet the private-label version costs roughly two-thirds less than the established brand.

In addition to taking the lead in price and quality in dry goods, discounters have become more innovative and are now succeeding not only in categories that consumer packaged goods companies have long considered to be “safe”—such as baby food, breakfast cereals, pet food, and personal care—but also in categories for which branding and marketing are paramount, such as beauty products. Discounters are raising their quality standards in some areas, such as packaging and design, as well.

-

Broader Assortment of Products. Discounters have also begun opening larger stores, with an average increase in size of 16%, over the past ten years. They typically use the additional space to sell a broader assortment of products. In addition, because discounters focus so intently on understanding what customers want, they can meet a wider range of needs, even though their stores are still smaller than those of traditional grocers and carry fewer products. As store sizes increase, discounters typically add fresh-food categories, such as produce and baked goods that are prepared onsite. Other additions include organic and gluten-free options and luxury products, such as lobster and quail. Many now have a large refrigerated section with prepared foods, dips, and soups as well.

Convenience is another recurring theme. In the Netherlands, the variety of fresh, ready-to-heat meals in aluminum trays that Lidl offers far exceeds similar options from some of its rivals. Discounters also limit the availability of new products for a short time, creating an aura of exclusiveness about them and encouraging customers to buy quickly so they don’t miss out.

- Improved Shopping Experience. Many discounters now offer extended opening hours, faster checkout service, and an upgrade of the look and feel of the stores, such as wider aisles, improved lighting, and digital signs. Lidl, for example, is investing roughly $3 billion to upgrade its stores in Germany over the next five years, and $1.5 billion on its stores in the UK over the next three years. Some chains are even testing innovative store features. At a new Lidl store in Belgium, for instance, shoppers can charge their electric cars and bikes for free; the capability is powered by nearly 1,000 solar panels on the store’s roof.

One thing that hasn’t changed, however, is the price advantage. Discounters’ prices are typically 15% lower than the private-label offerings from established grocers, and up to 200% lower than branded products at traditional grocers. As discounters have increased the size of their stores and added new features and products, they’ve focused on higher-margin offerings. As a result, they’ve managed to keep their operational costs down while boosting store productivity, which has pushed their margins higher. (For a case study, see the sidebar.)

HOW ONE DISCOUNTER KEEPS COSTS DOWN AND MARGINS UP

To understand the success of discounters, consider one discount chain that operates in many developed markets and has been expanding rapidly. The company has a highly efficient and profitable operating model and lower costs, particularly in labor. Its gross margins are approximately 8 percentage points lower than those of supermarkets, yet its margins for earnings before interest and taxes are higher—about 5%, beating the average supermarket chain by about 2%. Here’s how the company has gained an edge:

- Rather than relying on suppliers to develop products, the company uses strict internal processes. For example, it designs packaging so that employees can read barcodes, stock products more efficiently, and make better use of shelf space.

- To reduce the cost of goods sold, it negotiates net-net buying prices with suppliers. Under that arrangement, the chain agrees not to charge suppliers for such things as bonuses, rebates, and funding. In return, suppliers cover other costs on their side, including packaging and logistics.

- The company pays above-market wages to attract employees, and it develops them through well-defined career paths, rigorous training, and extremely high standards. That leads to lower attrition rates, a result that reduces the cost of replacing departed employees—and ultimately boosts margins.

- Although the company pays employees more than its competitors, it keeps labor costs down through a supply chain that is built to minimize in-store logistics and to maximize the efficiency of store workers. For instance, store labor schedules are carefully aligned with delivery schedules.

In fact, that price advantage is becoming more transparent to shoppers. Unlike in the past, the broader assortment of products now available at discounters means that the prices for items purchased during a typical shopping trip at a discounter are easily comparable with the prices for items purchased at a traditional grocer: shoppers can literally compare apples with apples. When consumers can buy essentially the same products at a discounter and easily see how much they saved, the challenge for established grocers gets even bigger.

Huge Shifts in Market Share

For established mainstream grocers in many markets, the growth of discounters has led to a pronounced drop in market share. Consider Ireland, for example. From 2000, when the first discount stores were launched, to 2015, discounters grew dramatically and took one-fourth of the market share from established players in the country. Some chains, such as Lidl, use Ireland as a test market for store innovations before exporting them to other locations; the country has become a talent incubator for Lidl as well.

The story in the UK is similar. Over the past ten years, discounters there have dramatically expanded their assortment of products, improved the store experience, and grown their profit margins. Mainstream grocers, on the other hand, have watched their margins shrink from more than 5% to less than 3%, with a corresponding drop in shareholder value.

But discounters can disrupt grocers even without taking significant market share from them. Because their product assortment is targeted to essential customer needs, discounters can sell a much greater volume of individual items and dominate a category. For example, a discounter in one market with just 18% share has 12 types of pasta available—compared with more than 100 offered by the established grocer in that market—yet it sells more than three times as much pasta in core product lines as the established grocer. This allows for a much more efficient supply chain arrangement with the manufacturer—including larger production sizes and full truck loads, for example—and thus lower product prices for the discounter.

Notably, discounters are not only winning over customers but also converting them into loyal brand ambassadors. Overall, discounters have a higher BAI than established grocers in most of the markets in which BCG tracks that metric. In part, this increased advocacy is because discounters today focus not only on value—the most important factor in BAI for the grocery industry—but also on such key areas as product assortment, store hours, fresh goods, and the overall shopping experience.

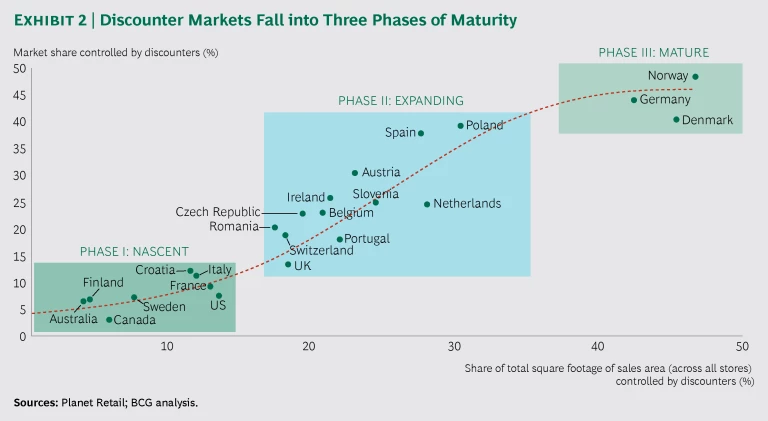

To better understand the dynamics of discounters and how much they will challenge established grocers, we identified three distinct phases of development with different levels of activity and success among discounters: nascent, expanding, and mature. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Nascent. In these markets, discounters have yet to establish a serious presence; they typically have market shares of less than 15%. And some of these markets—including in the US, Sweden, and Australia—are still essentially white spaces. They present an opportunity for discounters to disrupt the market, and some are already taking steps to do so. For example, Lidl is planning to open 20 stores in the US in mid-2017 and another 80 during the subsequent 12 months. Those stores will be significantly larger than Lidl’s European locations, with elements such as cold beer and free bakery samples. In addition, Aldi, which operates in some US states, will revamp 1,300 of its stores and open another 650 by 2018, for a total of more than 2,000.

- Expanding. In expanding markets, such as those in Belgium and Poland, discounters have established a foothold and begun to take significant market share: approximately 10% to 40%. They have strong operating models in place, with high sales productivity per square foot, and they are continuing to grow by replicating that model through newly opened locations. Lidl plans to open 200 locations in Poland, along with 100 in Romania.

- Mature. In mature markets—such as those in Norway, Germany, and Denmark—discounters have taken more than 35% of market share. Established grocers in this type of market can still react, but they can no longer get ahead of the threat.

In response to the industry’s changing dynamics, some established grocers may decide to do nothing. In nascent markets, for example, doing nothing may be the best option. Yet most grocers will need to take action. On the basis of our analysis, we see two strategic options that mainstream grocers can take to respond to the changing dynamics in the industry: revamp the operating model and costs or create a spinoff discount brand.

Revamp the Operating Model and Costs

The first strategic action is to fundamentally improve the company’s operating model and to reduce costs in such a way that management can justify the remaining price differential with discounters to its customers and shareholders. This response—which is less a suggestion and more of an imperative for many established grocers—requires more than a few incremental tweaks here and there. Instead, companies need a major transformation in multiple areas.

Reduce the price gap with discounters, especially for price-sensitive products. Mainstream grocers will never completely eliminate the price gap with discounters—and they don’t need to. They just need to be competitive in the areas that are most important to customers.

For example, consumers are often very price sensitive about commodity-type products, such as canned goods, paper products, and cleaning supplies, which are not highly differentiated. In these areas, grocers need to be more aggressive about price reductions. Conversely, in some fresh-product categories—such as the deli counter, butcher, or seafood counter—consumers are far less price sensitive (with some exceptions) and more willing to pay for service. In these areas, grocers can capitalize on their advantages: more customers, higher volume, bigger stores, and more developed supply chains. To take advantage of this split, grocers need deep customer insights to understand which departments and products really matter to their customers, where they can win, and how they should target their investments and improvements.

Scale back operating costs. Improving prices also requires decreasing operating costs and the cost of goods sold. Options include reducing the total loss of unsellable food that gets thrown away, using labor more efficiently, changing the assortment to reduce supply chain complexity and cost, negotiating pricing and other terms with suppliers, and introducing private-label products. For a typical mainstream grocer, cutting prices by 5% requires a reduction of either 7.5% (roughly) in the cost of goods sold or 20% in operating costs.

For example, in Portugal, grocery chain Pingo Doce streamlined its internal processes in a number of areas to increase efficiency and reduce costs. The chain, which has about 400 locations, simplified its product assortment (including private-label goods), reducing the number of options from seven or eight in any given category to three or four, and then required a clear business case before it would consider raising that number again. It also consolidated purchasing volumes into larger orders with fewer suppliers in order to gain scale, and it improved its logistics processes. As a result, the company increased its average sales volume per product by 600%, generating scale and improving the efficiency of its logistics. It also decreased inventory levels by two-thirds, while reducing out-of-stock items.

Similarly, mainstream grocers in France have managed to fight off the challenge from discounters over the past decade. They aggressively reduced prices on many national brand products to match the level of discounters. They introduced value-based, private-label goods—again matching the prices at large discounters—and removed from store shelves many of their so-called price-fighter products, which shoppers regarded as low quality, replacing them with higher-quality products and brands at lower prices.

Redefine the customer value proposition. Once companies have done everything they can to trim operating costs and reduce the pricing gap, they need to determine the right value proposition to justify the remaining difference. (Our analysis shows that the prices of even the best-performing grocers will still be 5% higher, on average, than those of a discounter.) Customers do not want the cheapest products; they want high-quality products that meet their needs, a clean store environment, helpful staff, and prices that seem to represent fair value. However, different customers define those criteria in different ways, so grocers need to understand their target customers and how they want to shop. Those insights, in turn, have ramifications for store design, product categories, and other forms of customer engagement with the brand.

For example, some grocers may target food lovers, who want the highest-quality products; a wide variety of fresh meat, produce, and seafood; and high levels of customer service. These customers are prepared to pay a premium for the right experience. Other grocers, however, may target urban shoppers who need small stores that offer a basic assortment of products and that are within walking distance of their home or office. These shoppers make frequent, fast trips, and they will pay a reasonable price difference for convenience. Still other grocers may target families, who tend to fill their shopping carts with enough food and nonfood items to last the week. These shoppers want low prices, regular sales and promotions, and a large store with a wide selection of products.

Once a company understands its target customers, it can revise its product categories to better meet their needs. That revision, in turn, will influence the assortment of products sold, the pricing and promotion strategies, and the overall customer experience.

Private-label products are also a critical means of reshaping the customer value proposition, particularly in dry goods. Some customers will always want name brands, and grocers will always need to stock them. However, grocers can develop private-label products that are as good as branded items and offer them at prices that are competitive with those of discounters. Doing so requires detailed customer insights and strong innovation processes, and companies that can capture this information and synthesize it in ways that lead to compelling new products can outperform established consumer packaged goods players. For example, 80% of the products sold at Trader Joe’s are private-label goods. In Spain, the Mercadona chain’s own brands now represent 55% of the company’s sales and 15% of all grocery sales in the country. Mercadona even has a successful cosmetics line, Deliplus, which is larger than L’Oréal in Spain, dispelling the conventional wisdom that customers won’t buy private-label cosmetics.

For both branded and private-label products, our experience shows that revising categories to better meet customer needs can lead to a material increase in sales.

Innovate to improve the customer experience. Grocers need to innovate in order to create a better experience for their customers, both in stores and online. For example, unlike discounters, most grocers have invested heavily to develop loyalty programs, and they run frequent promotions across their broad assortment of products. Viewed from one perspective, such factors could be a disadvantage; they make the store experience complex and add operational costs.

But established grocers can turn those factors into an advantage by applying the underlying technology to connect more directly with consumers and create personalized offers. Some 80% of smartphone owners, for instance, want to be able to get product information on their phones while they’re at the store, and more than 40% look for deals on products while shopping. A retail chain in South Korea has capitalized on these trends by developing a mobile in-store navigation app that guides customers to on-sale items and sends instant coupons to their phones. Similarly, French grocer Carrefour is testing an app that guides shoppers to their preferred promotional items in stores. (It uses the phone’s camera and is accurate to 1 meter, versus 3 to 5 meters for mobile GPS systems.)

Along the same lines, many mainstream grocers—both national and international chains—have already made major investments in IT as part of their higher overall operating costs. They can use technology to improve the digital commerce process for customers or to more effectively link the online and in-store experiences.

A final example is staffing levels. Despite the efforts of discount grocers to increase the sizes of their stores, traditional grocery venues are still much larger. As a result, they invariably have more employees per store than the discounters do. Trying to reduce costs by eliminating some of those employees will only demoralize the remaining staff and degrade the experience that customers receive. Instead, companies should invest in training initiatives so they can offer outstanding service.

For example, Wegmans Food Markets deliberately fosters a “family feeling” among both staff and customers by creating stores with the look and feel of open-air markets. Customers can shop for groceries, get a coffee at the Buzz Coffee Shop, and order a healthy snack at the organic salad bar. The company’s engaged workforce delivers excellent customer service, and Wegmans has made Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For list every year since 1998. Despite all these initiatives, Wegmans’ prices are still competitive on key items, and the company has cultivated a base of devoted brand advocates. As a result, the chain has grown at a rate of 7% a year over the past five years.

Create a Spinoff Discount Brand

The second strategic option for an established grocer is to launch or acquire a spinoff discount brand to supplement the grocer’s established brand. This is particularly attractive in markets where discounters haven’t yet established a major presence and where the growth in food prices—and grocery margins—is still high. The US, Sweden, and Canada are examples of such markets.

Some grocery chains have already taken this path. For instance, in Canada, Loblaw launched its “No Frills” discount brand in 1978. Today, the chain comprises 250 franchised stores that feature Loblaw’s private-label brands, including everyday basic items under its “no name” brand and higher-quality goods under its “President’s Choice” brand. The chain offers a narrow assortment and limited service, leading to highly competitive prices.

That said, the overall track record of grocers attempting to launch a discount brand is mixed at best, with more failures than successes. Accordingly, management teams will need to thoroughly consider several factors, including the following:

- Draw clear lines to separate the spinoff brand from the core business. The separation applies to such key aspects as management, financials, procurement, and marketing. Moreover, the new brand needs sufficient leeway to develop its own culture, ways of working, and processes. The experience of the companies that have done this successfully suggests that one aspect that should not be independent is purchasing. Instead, the spinoff brand should be able to capitalize on scale efficiencies by purchasing products through the core business.

- Be willing to invest heavily at the beginning. The amount of cash needed to launch a new brand can be significant, especially given the imperative to establish the brand quickly and to do so in the face of strong marketing efforts from competitors. In an industry with razor-thin margins, management must have the fortitude to make such a big bet and to forgo cash that might otherwise have been used to strengthen the core business.

Strategic Priorities for Discounters

Most discount grocers have a heritage of simplicity and superb execution. Nevertheless, and despite the promising environment for discount grocers right now, companies must avoid pursuing growth opportunities that pull them away from their main areas of expertise and competitive advantage, as many have done in the past.

For example, larger stores with enhanced features require greater capital investments. And a broader assortment of products means that supply chains and supplier relationships become more complex—especially when some of those products are either prepared foods and produce or organic goods. For example, in Australia, Aldi shifted from buying fresh produce on the spot market, where it could get the lowest prices, to a more centralized model involving longer-term contracts with suppliers. That has meant paying higher prices at times in order to lock in a predictable supply of produce that meets the company’s quality standards.

The economics of store labor change as well. It takes far longer for a store associate to sort and stack fresh fruits and vegetables by hand—while minimizing losses—than to put cans on shelves. (Smart discounters get around this by developing innovative cartons and crates with attractive designs that display produce without requiring it to be stacked by hand.) Similarly, offering prepared foods requires hiring employees with specialized skills.

Overall, there is a risk that discounters will deviate from their successful business model—built on a small assortment of products, high volume, and lean, cost-efficient execution—and try to compete in ways that favor established grocers. (Already, a few discounters have undergone management changes due to these kinds of growing pains.) To avoid this fate, discount management teams should make sure that they are maximizing their efforts in the markets where they currently operate before expanding into new ones—particularly in large countries, such as the US and Australia, which require sprawling distribution networks. They also need to carefully analyze which markets make the most sense to enter, how many stores they should open in those markets, and what the distribution infrastructure should look like. Above all, they need to avoid sacrificing their highly efficient operating model in pursuit of a more attractive customer experience.

Discounters in many markets have triggered a major disruption for the grocery industry over the past decade—a disruption that will continue. By evolving the way they operate—and becoming more innovative in how they develop new products to meet customers’ needs—they are taking greater market share from established grocers. But they need to avoid overexpanding and introducing too much complexity into their simple operating models, which have worked so well. Incumbent players need to decide on the right strategic response—transforming their operations or launching a discount brand of their own.

Both groups, however, face similar challenges: to identify the needs of their target customers, offer them a unique experience, and strike the right balance between complexity and efficiency. Customers can be extremely loyal to their favorite grocery chain. Companies that understand the underlying factors of that loyalty will position themselves to win.