This is the first in a series of articles highlighting lessons from China on the future of retail. The second article explores how the The Chinese Consumer’s Online Journey from Discovery to Purchase . The third looks at how companies can What China Reveals About the Future of Innovation . The fourth focuses on how retailers can How Companies in China Blend Digital and Physical Commerce .

Imagine being in the middle of Times Square, surrounded by flashing lights, fast-talking vendors, street performers, live music, noisy traffic jams, and endless other distractions. Now imagine you’re online and surrounded by the same energetic chaos. Welcome to China’s digital marketplace, where shopping is an adventure—a fire hose of rapidly changing content, offers, products, colors, and choices. For Western shoppers accustomed to simple, transactional online buying, it’s a culture shock.

China has more e-commerce activity than any country in the world today. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, Chinese consumers spent $750 billion online in 2016—more than the US and the UK combined. That is a jaw-dropping number, but even more interesting is how differently China’s digital marketplace, technology platforms, and online behaviors have evolved compared with those in Western markets. These differences provide a glimpse into the future of shopping—and offer valuable insights for companies around the globe. This article, the first in a series on the future of retail, provides an overview of e-commerce in China today and explores some of those key differences.

The Digital Revolution Goes Mobile

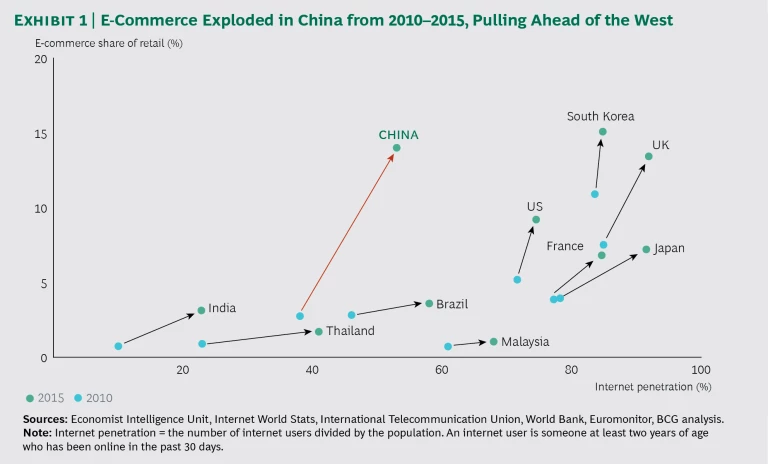

When Amazon and e-tailing disrupted US shopping in the 1990s, retailers and consumers alike had to rethink their deeply ingrained habits. By contrast, physical retail in China was less developed. The digital revolution coincided with the growth of disposable income and consumption. As a result, e-commerce quickly became the norm, and its development was fast-tracked to the point where China pulled ahead of the West. (See Exhibit 1.)

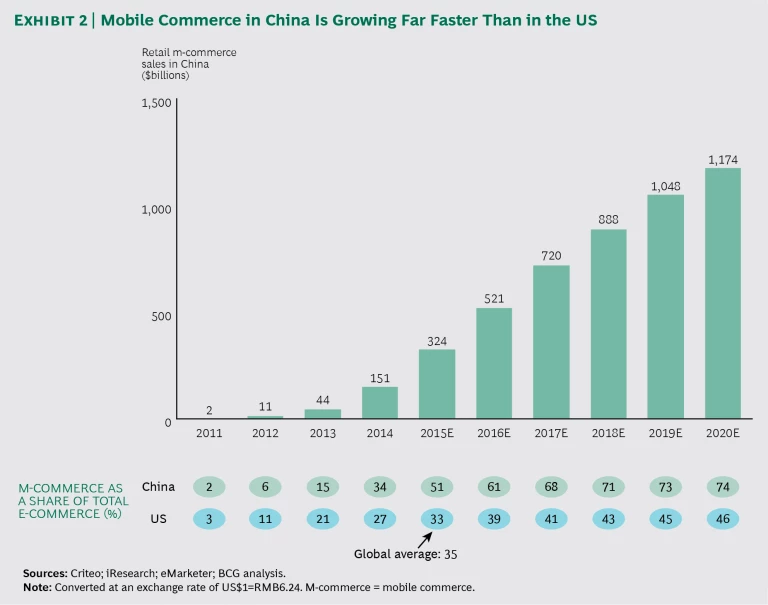

China is also a pioneer in mobile commerce. (See Exhibit 2.) Many consumers skipped the PC era entirely, going right to smartphones. This may explain why Samsung phones with larger screens took hold in China well before they did in Western markets. According to industry estimates, online purchases made with mobile phones will account for 74% of total e-commerce in China by 2020, compared with just 46% in the US.

The pace of e-commerce doesn’t seem to be slowing: the industry is expected to grow by 20% annually in China over the next five years—twice as fast as in the US and the UK. This growth will be driven not only by increased individual spending but also by an expected influx of hundreds of millions of new consumers, many from smaller cities and rural areas, who have yet to go online.

As part of this growth, we expect to see higher e-commerce penetration in product categories that may be surprising for the West. Today, Chinese consumers buy everything from organic foods to luxury cars online. Over the next five years, online shopping will spread and deepen across a wide range of categories. According to some projections, just five categories in the US— such as books and clothing—will capture more than 40% of e-shoppers. In China, 15 categories, from snacks to financial services, will reach this level of penetration.

E-Commerce Edge

China’s unique retail history has given rise to one of the most advanced digital marketplaces in the world. With its sophisticated shoppers, massive volume of transactions, rapid rate of innovation, and integration of social media, multimedia, and other channels, China’s online environment offers a glimpse into the future.

A few key characteristics of consumers, brands, and shopping platforms in China’s online landscape clearly differentiate it from online marketplaces in the West.

- Chinese consumers are eager to spend money—and they spend a lot of time shopping. In China, shopping is about more than just the transaction. It’s about entertainment, discovery, and social engagement with friends, celebrities, and internet influencers. On average, China’s consumers spend almost 30 minutes a day on Alibaba’s Taobao, the country’s leading e-commerce marketplace, nearly three times longer than an American consumer typically spends on Amazon. And they’re very brand conscious, if not particularly brand loyal. For instance, the typical Chinese teenager can recall 20 cosmetics brands while the average US teen can identify just 14. China’s young people are also the most “spend friendly” in the world: 42% feel the need to buy more things, compared with 36% in both the UK and the US.

- Intense brand competition drives constant innovation. Established players and upstarts alike continually create new offerings and service models to stay one step ahead of the competition. In highly competitive categories such as cosmetics, dairy, and confectionery, market leadership constantly changes as new entrants jockey for attention. Online merchants in China are not afraid to test new products, fail, and try again, rather than adhering to a rigid schedule of product launches. They’ve become increasingly sophisticated in their use of multimedia and multiple channels to reach and engage consumers. What’s more, they’re at the forefront of using data, analytics, and consumer insights to better understand the customer—and are moving toward true consumer-driven product development.

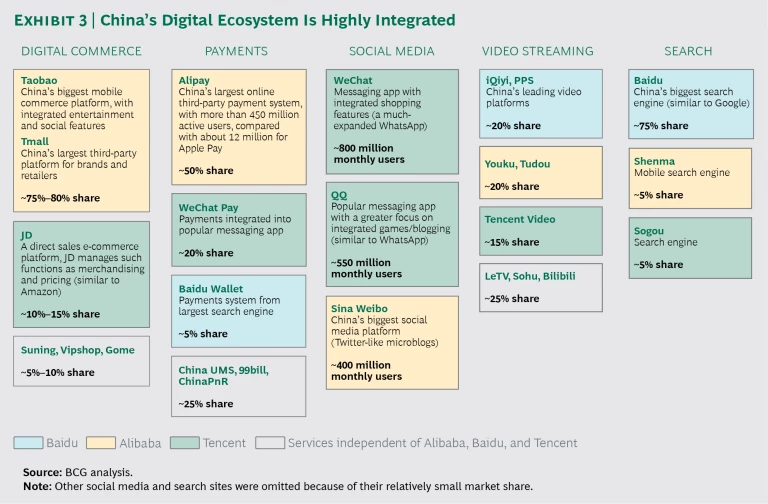

- Seamless, integrated platforms make shopping fun—and buying easy. In China, news sites, games, videos, and e-commerce are all interconnected in the major online hubs, with click-to-buy product placements and quick links to payment options. (See Exhibit 3.) Unlike online shoppers in other countries, Chinese consumers rarely visit company or brand websites. Instead, they discover what they want to buy through online marketplaces such as Taobao, entertainment apps like iQiyi, and WeChat, China’s most popular social media platform. Taobao and WeChat, two of the top five apps in China, have evolved into all-in-one super apps. Taobao, which began as solely an e-commerce site, now offers social and entertainment features. WeChat, which started as a social platform, now allows users to buy and sell products. These super apps also provide a wide variety of online and offline services. Users can send money to people, order food, call a taxi, set up a doctor’s appointment, pay bills, and get movie tickets. In the US and UK, consumers would need a different app for each of these activities.

A Tale of Two Giants: Alibaba and Amazon

Another way to better understand the differences between East and West is to examine the key players in each market: Alibaba and Amazon. On the surface, they seem very much alike. Both offer online marketplaces, each holds a leading market share, and each is continually expanding into new ventures. Although both companies are enormously successful, their business models are quite different.

Amazon is the quintessential online retailer, carrying its own inventory and focusing almost exclusively on the consumer. Most shoppers come to Amazon looking for a specific item. The site’s virtually unlimited selection, excellent search engine, low prices, user reviews, product recommendations, easy payment, rapid delivery, and first-rate service have built a base of very loyal customers. Over the years, Amazon has expanded into many different lines of business and services, such as Kindle e-books and e-readers, video streaming, original TV shows and movies, and food delivery.

By contrast, Alibaba doesn’t carry inventory or buy and sell merchandise. The company operates like a virtual mall, providing wholesalers and retailers with platforms that connect buyers and sellers. In this e-marketplace model, brands “own” their relationship with customers and create online experiences appropriate to their individual brands. Alibaba offers tools and services to help brands and small businesses navigate the world of e-commerce and connect directly with consumers through games, news, video, live-streamed talk shows, celebrity events, and online communities. Consumers go to these sites to be entertained and to explore new trends—as well as to shop. Underlying these capabilities is Alibaba’s technology, which integrates its e-commerce marketplaces, such as Taobao and Tmall, with digital marketing, payment, and logistics services, as well as social media, entertainment sites, and news portals.

Unilever China’s experience offers an example of the power that Alibaba can harness for merchants. Unilever used a live-streamed game show video to promote its soaps and shampoos, as well as a technology that allows merchants to distinguish regular shoppers from new ones, displaying tailored shopping pages when consumers visit the company’s online stores. In the first two weeks of using Alibaba’s technology, Unilever saw the average time spent by shoppers at its virtual stores increase by 26%.

Data and analytics are crucial to both Amazon and Alibaba, but they are used in different ways. Amazon uses data primarily to refine its product and service offerings on the basis of consumer buying patterns. The company also shares data with merchants to help them list the right products, price competitively, and manage inventory. Alibaba provides a broad data set on consumer behavior that enables merchants to improve their marketing ROI and increase the conversion rate on their digital storefronts. For example, the data might reveal that a merchant’s highest-value customers visit after work—so a campaign might have a greater impact in the evening than in the daytime.

Alibaba can provide these powerful analytics because of the rich data it draws from its large ecosystem. As consumers move seamlessly through its various sites, Alibaba collects information on their shopping habits, digital media consumption, logistics needs, payment and credit history, search preferences, social networks, and internet interests to better understand their behaviors and needs—using a “unified ID” to link consumer data across different sites. Drawing on its detailed data on nearly 500 million monthly active users, Alibaba has identified 8,000 different consumer descriptors, so that merchants can home in on their target customers with extraordinary precision—and increase the effectiveness of their consumer engagement efforts.

Alibaba also uses this data to provide a truly personalized shopping experience for the consumer, to a degree not yet seen in the West. So while Amazon offers product suggestions based on a consumer’s searches or buying history, Alibaba may suggest new brands, promotions, or content that consumers didn’t even know existed. And those suggestions tend to be spot on, driving exceptionally high click and follow-through rates. Few companies—if any—in the US or Europe have elevated data analytics and artificial intelligence to this degree.

New Retail

Today, retailers in China and the West face the same challenge: how to achieve ongoing, profitable growth. Many of the costly big-box stores and shopping malls are losing customers and profits to online sales. In China, many homegrown brands have existed only online. To achieve growth, they must expand offline—especially in urban areas.

The solution for both Chinese and Western retailers is to develop an integrated omnichannel model that capitalizes on online and offline strengths, delivers a seamless and compelling customer experience, and increases efficiency in inventory management, product selection, and logistics. In this new world, the distinction between online and offline commerce disappears, and the way the consumer thinks and behaves across all channels determines the way the merchant runs its business. Players focus on engaging the customer through personalized content. And they develop capabilities across marketing, innovation, and logistics to adapt to ever-evolving customer needs. Alibaba calls this new retail.

Future articles in this series will explore the concept of new retail at length and dig deeper into critical dimensions of China’s vibrant digital marketplace, such as the customer journey, innovation, and omnichannel optimization. These articles will offer important insights for companies in the US and Europe that want to understand China’s unique differences and apply that knowledge to their own domestic markets—and get a head start on their competition.