This is the second in a series of articles highlighting lessons from China on the future of retail. The first article looks at how consumer behavior in China is evolving . The third explores how companies can What China Reveals About the Future of Innovation . The fourth focuses on how retailers can How Companies in China Blend Digital and Physical Commerce .

Much has been written about the move online by Chinese consumers and the country’s explosive growth in ecommerce. Less well understood is how Chinese shoppers use the internet—and how their buying experience differs from that of consumers in other markets.

In the West, ecommerce originally emerged as a more efficient way to shop. Today, consumers still go online to shop because it is often easier, faster, and more convenient than going to a store. Many ecommerce players optimize their platforms for efficiency by building search functions, payment features, and delivery capabilities. They want customers to shop frequently and quickly.

In contrast, ecommerce in China has been about providing a richer alternative to traditional shopping. Consumers like to spend time in a discovery-driven online world of energetic chaos where shopping is an adventure. Ecommerce players optimize their platforms for customer engagement, blurring the lines between entertainment and ecommerce as well as between online and offline commerce. Shopping is a social experience, not a solitary one. The Chinese consumer’s unique path from prepurchase to purchase holds valuable lessons for retailers in the West.

This article, the second in a series on the new retail concept, explores the differences between the buying experience of Western and Chinese consumers and provides a window into what may be the future of shopping.

Search Versus Highly Personalized Discovery

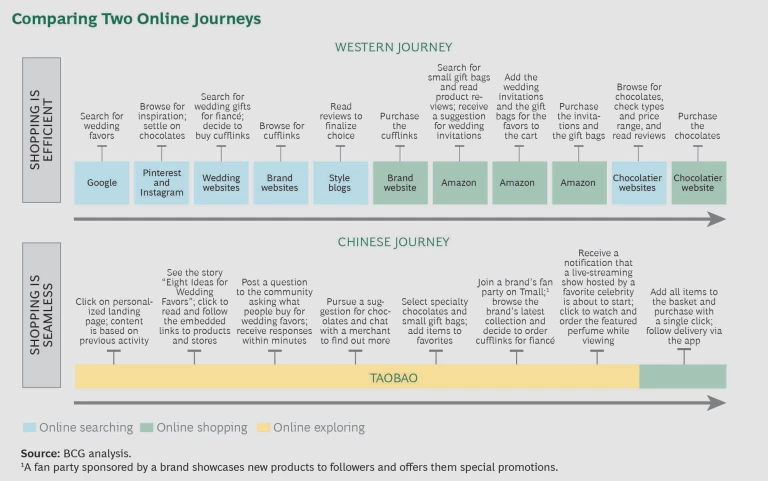

Because online shopping is often optimized for efficiency in the West, customer behavior in the prepurchase phase is mostly about searching. Consumers typically go to an online retailer, such as Amazon, or a company’s website with a specific item in mind. Category details—such as product, style, color, and size—help buyers drill down and narrow their search. The payment page is automatically filled with personal details to speed the transaction. Mission accomplished! The online shopping experience is fast, smooth, and easy. (See the exhibit.)

In China, the typical consumer behaves very differently. Instead of searching for specific items online in the prepurchase phase, Chinese consumers embark on a journey of exploration and discovery—as if they are going to the mall with friends or family. Chinese consumers go online to see what’s new or what’s trending, sometimes many times a day. This is partly because of the highly personalized and rapidly changing nature of the online shopping experience, which not only enables product discovery but also helps consumers make lifestyle choices.

Online merchants in the US offer product suggestions on the basis of a consumer’s searches or buying history. Marketplaces such as Alibaba’s Taobao in China use such data as well, but they also capture other types, such as social interaction and location data, and employ analytics, artificial intelligence, and personalization. The result is a curated shopping experience achieved by few—if any—companies in the US or Europe. Everything consumers see on their screen is customized and updated in real time. Suggestions—whether for promotions or new brands or content—tend to be spot-on, even those that are for items consumers didn’t know they wanted or needed. Such experiences drive exceptionally high click- and follow-through rates, as well as longer online visits.

China’s shoppers rarely make an online store their destination. In addition to receiving suggestions from an online marketplace, Chinese consumers discover new brands and products through an array of digital channels and content. For instance, they may see an item they like on social media, in a music video, in an online fashion show, in a makeup tutorial, or on a news site.

China’s integrated digital platforms enable this content-led discovery. Even though many of the engaging online channels are not overtly related to shopping, if Chinese consumers see something they like, they can buy it immediately through embedded purchase links. As a result, the path from discovery to purchase is seamless. These instant “buy what you see” opportunities take product placement and ease of purchasing to the next level—one not yet seen in Western markets. In the US, when consumers see something they like on Pinterest, Facebook, or WhatsApp, they usually have to exit the app to search for the product and buy it. China’s version of Pinterest, Xiaohongshu, is an ecommerce site where consumers can buy what they see right there. In other words, in China, discovery and purchasing are integrated, whereas in the West, they are separate.

Myriad Ways to Discover

Like consumers in the West, China’s consumers go online to be entertained, to educate themselves, and to share with friends on social media. The important difference is that in China, buying opportunities are woven seamlessly into these activities. Merchants partner with content providers and key opinion leaders, such as celebrities and experts, to create innovative, engaging online experiences that generate buzz, draw in consumers, and lead to sales through embedded purchase links. Although some companies in the West have experimented with content-driven discovery, it is not yet commonplace. In contrast, as the following examples show, China’s digital environment is rife with experimentation:

- P&G and Memebox offer video tutorials using well-known makeup artists. For a generation of only children who don’t have a big sister to go to for advice, tutorials such as these fill an important need.

- Baby Tree embeds purchase links to featured products in its content that focuses on baby advice and motherhood. An educational portal and growing ecommerce site that has an online community of 30 million users, Baby Tree enables brand and merchant partners to leverage its user base.

- Tmall offers buyers a “digital mirror” app for their smartphones. The mirror lets online shoppers virtually apply as many as 2,000 makeup shades from well-known brands, such as L’Oréal and Bobbi Brown. Users can take selfies, share the photos with friends, and buy products directly from the app.

- On WeChat, China’s most popular social media app, cybercelebrities with big followings promote their brands by posting messages to their network—messages that include not only their products but also a payment button so consumers can buy on the spot. Similarly, celebrities on Taobao who have more than 1 million followers can monetize their fame by selling directly. On both platforms, celebrities have become online entrepreneurs, building large internet businesses. Although revenues from these ventures account for only 7% of the total e-retail market, the social media channel is growing in importance as a driver of brand awareness and sales.

- On Taobao, Tmall, and JD.com, China’s leading online marketplaces, merchants can promote their products by live streaming events, not unlike the TV shopping channel QVC in the US. For instance, rural farmers used Taobao’s live-streaming feature to market their kumquats for the Chinese New Year. But China’s live streams tend to engage more consumers, since they often feature well-known experts or popular internet celebrities—and a direct purchase link, of course. According to China Tech Insights, an industry research project, live-streaming revenues reached $246 million during the summer months of 2016 alone. On Taobao, every 1 million views results in 320,000 items added to customers’ shopping baskets. Some industry observers believe that live streaming will become a standard feature on China’s ecommerce platforms in the not-so-distant future.

In China, market influence is an ongoing, two-way street, driven by merchants and consumers alike. New concepts created by brands and merchants attract consumers’ attention and curiosity, which then inspire another cycle of innovation and discovery.

The Next Big Things in Consumer Discovery

As the examples above make clear, merchants and brands in China are moving toward an integrated omnichannel retail model that capitalizes on the strengths of online and offline commerce, delivering a seamless, compelling customer experience. In this new world, discovery is ongoing, all the time—online, offline, and across all channels. We already see some examples of this in the West with the AmazonFresh click-and-collect model and the Starbucks loyalty app. Ultimately the distinction between online and offline commerce will disappear.

This future is coming faster to China than to the West. In the West, the prepurchase, purchase, and postpurchase phases of the consumer journey are segmented across channels and online platforms. This lack of integration drives the transactional nature of ecommerce activity. In China, the phases of the purchase journey are much more integrated, so the online and offline experiences are more seamless.

This online-offline integration is blurring the distinction among channels. It’s happening more quickly in China for two reasons: ecommerce technology is more advanced, and physical retail is less developed, so there’s a smaller base of legacy stores to protect. There are several signs of this new future:

- Alibaba is experimenting with virtual reality through its Buy+ events, which were introduced last fall. The events use virtual reality to make online customers feel as if they’re at a physical mall that has global merchants, such as Costco, Target, and Macy’s. More than 8 million shoppers have tried out the experience, using embedded purchase links to quickly buy items that caught their eye.

- China’s Wumart, a leading grocery retailer with more than 1,000 stores, recently launched a mobile wallet that customers can use to simplify payment during checkout in physical stores. The offline customer transaction data collected by the app is then integrated with the customer’s online account, giving the retailer a full omnichannel view of the customer. Drawing on this rich data set, Wumart can recommend products and promotions to customers and increase the appeal of its merchandise.

- Last year during 11/11 (China’s version of Black Friday), Alibaba worked with more than 1 million stores across various product categories to present shoppers with an integrated online-offline experience. For instance, customers who bought items at the Gap’s online store could have them shipped to the nearest brick-and-mortar Gap store—in hours instead of days. At the physical stores, shoppers could scan a QR code to buy an item and have it shipped to their home.

In this integrated future, merchants and brands will make business and merchandising decisions in response to how consumers react to and behave across all channels. (See “Understanding Chinese Consumers.”)

UNDERSTANDING CHINESE CONSUMERS

With strong growth of consumer spending projected in China over the next five years, global retailers are taking notice. But who’s doing most of the buying? The typical Chinese consumers are young, live in urban areas, are part of the growing middle class, and save less than their parents or grandparents despite earning a sizable income. Although China’s economic growth is slowing, these consumers are optimistic that their earnings and standard of living will increase over time. And as their income rises, they buy more premium products, trading up to healthier food and pricier cosmetics.

Although more brand aware than consumers in the West, Chinese consumers are not necessarily brand loyal. With the exception of luxury goods, loyalty to global brands is waning. In fact, these consumers are open to new products and brands—especially those that engage them with innovative offerings and the creative use of multimedia.

The typical Chinese consumers do more than half of their online shopping using a mobile phone, increasing the likelihood of shopping at all times, whether on the bus, in an elevator, or at work. By contrast, Western consumers typically spend two-thirds of their day on laptops and only one-third on a mobile device.

Building a Discovery-Driven Consumer Journey

Online merchants and brands that build effective discovery-driven consumer journeys are more likely to deepen consumer engagement and generate higher sales volume. Although some Western companies are beginning to move in this direction, their Chinese counterparts tend to be far more advanced. To increase the discovery aspects of their online experience, retailers should consider the following questions:

- How can we personalize the consumer journey even more? To most online merchants in the West, personalization means greeting the consumer by name and making product suggestions on the basis of past searches or purchases. Instead, retailers should go further and use data and analytics to customize the shopping journey on a deeper level. For instance, merchants could offer different pathways for different needs: automatic replenishment for basic items, social media for major purchase decisions, live shows for splurges, and so forth. Some Western brands are beginning to experiment with this. Sephora’s Virtual Artist tool helps users develop a personalized product wish list using their in-store and online history.

- How can we use online content to build our brands? In China, creatively using content and multimedia is an integral part of ecommerce and brand building. Merchants take traditionally offline experiences—such as fashion shows or game shows—and scale them online to reach a much broader audience. Investments such as these turn transactional commerce into experiential commerce, while changing consumer expectations and behaviors. Some Western companies are already moving in this direction. Burberry, for example, has been using live events to engage consumers in “see now, buy now” purchases.

- How can we develop a social commerce business? Traditional social marketing advertises brands or products through embedded links and posts on social media. Social commerce requires creating social content—such as online events or celebrity-hosted tutorials—that can generate buzz, live conversations, brand recommendations, and sales.

- How can we make the path from discovery to purchase more seamless? In China, ecommerce technology, such as Baby Tree’s product links or Tmall’s see-now, buy-now functionality, is often embedded in the content. This type of marketing content builds brands while driving sales.

- How can we develop an integrated consumer journey on our mobile platform? In China, online merchants and brands know that discovery happens on the go. They understand how consumers use their mobile devices and build mobile platforms to make buying seamless. For example, Keep, a health and fitness startup, allows customers to purchase sports equipment directly from the app they use to monitor their workout. Western companies that want to convert internet surfers into buyers must do more than adapt their website to run on a mobile device.

Making this shift toward a more discovery-led consumer journey requires a deep evolution in a company’s operating model and capabilities. We’ll address these changes in the next article in our series.