This is the first of three articles on the sharing economy. The goal of our research was to understand whether the sharing of rides, apartments, and even clothing is a passing fashion or an enduring and relevant trend for business leaders. We interviewed more than 25 founders and CEOs of sharing-economy startups across the globe and surveyed more than 3,500 consumers in the US, Germany, and India.

This article focuses on opportunities created by the sharing economy, consumer attitudes toward sharing, and the industries likely to be affected. The second article will examine the strategic options that sharing offers, while the third article will reflect on the future of sharing in the global economy and the specific business models that are likely to succeed.

T he sharing economy is shrouded in several misconceptions: First, it’s a playground for millennials, who will outgrow their fascination and eventually prefer buying. Second, it’s largely irrelevant for most industries, outside of taxi fleets and hospitality. Finally, if the sharing economy ever does become relevant, it will be a threat to the industries in which it takes root.

For most global incumbents, however, these views are misplaced. The sharing economy is real, relevant, and a tangible opportunity rather than a temporary distraction, a passing fad, or a threat. It can create new revenue streams and market opportunities. And by understanding the economic and behavioral rationale for sharing, incumbents can shape developments to their benefit.

Sharing Makes Economic Sense

Rural India is a long way from Silicon Valley, the birthplace of the sharing economy. But Mahindra & Mahindra, the automotive arm of Mahindra Group, saw an opening for a sharing business in India’s vast countryside. Only about 15% of the subcontinent’s 120 million farmers use mechanical equipment. The rest cannot afford the cost of ownership, and existing rental arrangements—often with relatives or neighbors—can be inefficient and complex.

To reach those farmers, Mahindra could have created lower-cost products by removing features or sacrificing quality. Instead, it created a sharing platform, Trringo, which allows farmers to rent equipment made by Mahindra (and even by its competitors) by placing a call. (To accommodate users without smartphones, Trringo operates call centers staffed with agents fluent in several local languages.) Trringo has given Mahindra a way to increase its customer base, build brand awareness, and, in the words of CEO Arvind Kumar, “play a pivotal role in driving rural prosperity by empowering farmers.”

In applying this innovative business model to the world’s oldest economic activity, Mahindra is pointing the way for companies that may not have recognized the sharing economy’s potential.

Seizing the Opportunity

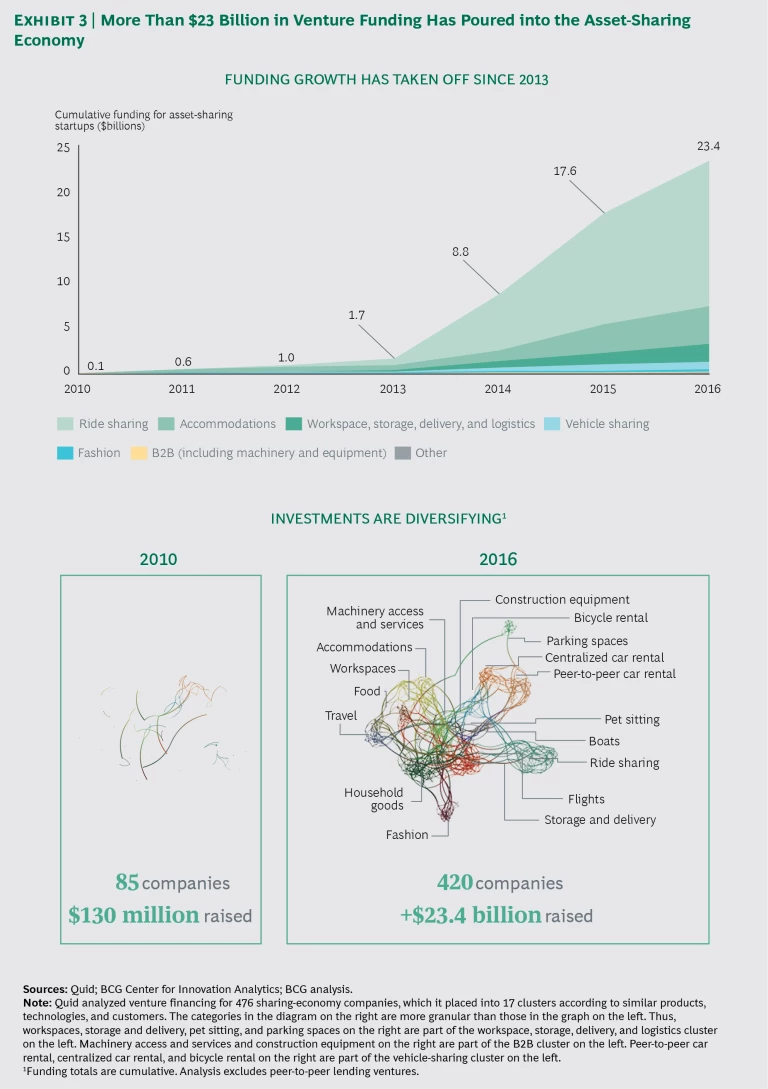

An estimated $24 billion in venture capital funding has poured into the market since 2010.

The sharing economy is a rapidly growing set of platforms that permit users to gain temporary access to various assets. (See the sidebar, “Three Sharing Models.”) An estimated $23 billion in venture capital funding has poured into the market since 2010. The total size of the sharing economy is much harder to estimate because most of the platform providers are private. But in its March 2017 funding round, Airbnb was valued at about $31 billion, or roughly the same as Marriott International after its acquisition of Starwood Hotels and Resorts Worldwide. In New York City, meanwhile, the Uber fleet is nearly three times larger than the number of yellow taxis.

Three Sharing Models

Three Sharing Models

Sharing businesses are not all the same. There are at least three distinct models, which differ according to who owns the asset and who sets the price and other conditions.

Decentralized Platforms. An asset owner sets the terms and offers the asset directly to the user. The platform makes the match and facilitates the transaction in exchange for a small share of the fee. This is the Airbnb model. Upfront capital costs are low, but the platform must recruit providers to ensure adequate supply.

Centralized Platforms. The platform itself owns the asset and sets the price. It has greater control over quality, availability, and standardization than a decentralized platform and collects a larger share of the transaction value, but costs to scale are much higher, too. This is the Zipcar and Rent the Runway model. It requires significant upfront capital and high utilization to be viable.

Hybrid Platforms. Asset owners offer a service with price and standards set by the platform. Ownership and risk are decentralized, while standardization and service level are centralized. This is the Uber and Lyft model. As with the decentralized model, upfront costs are low and provider recruitment is crucial. The platform must also carefully manage its relationship with providers, since they have less control than they would under the decentralized model.

The sharing economy creates new potential sources of revenue and profit in at least two ways.

Expanding Markets. As Trringo demonstrates, the sharing economy can attract new customers who cannot afford to own a product or do not have sufficient need to do so. ShareGrid, a US camera rental platform, is expanding access to high-end equipment for photographers and other creative professionals. Boatbound, a US leisure-boat rental firm, offers consumers the chance to enjoy an afternoon on the water without the cost and burden of ownership.

Boats and cameras have long been available for rent at selected boatyards and stores, but sharing platforms have several advantages. By bundling additions such as insurance and allowing consumers to make a deal on their smartphone, they reduce the hassles involved in renting. They also greatly expand the supply of available products as well as demand, which is no longer dependent on walk-in traffic. The platform monitors quality and provides customer service. A national business such as Rent the Runway’s Unlimited daily wardrobe-rental service would not have been possible before smartphones gave users the freedom to browse, select, and order designer clothing in the time it takes to walk into their own closet. (We discuss many of these issues in our second article, which examines how connectivity and lower transaction costs have facilitated the creation of the sharing economy.)

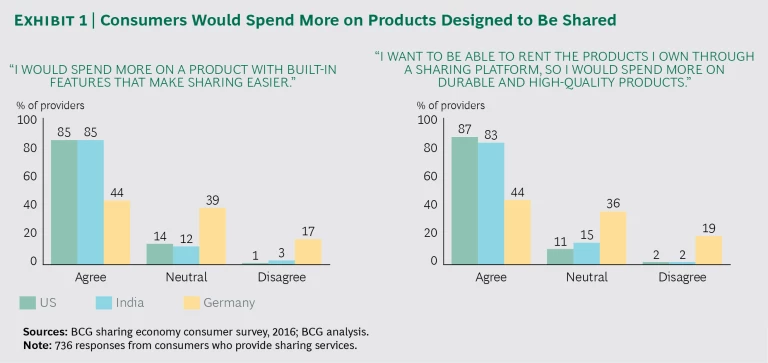

Increasing Willingness to Pay More. Consumers are willing to pay higher prices for goods that can generate a revenue stream by being shared. According to our survey, more than 80% of people who provide sharing services in the US and India, and more than 40% of service providers in Germany, would spend more for especially durable and shareable products. (See Exhibit 1.) This can translate directly into new or enhanced product lines for manufacturers—for example, tools, equipment, and vehicles with features such as keyless ignition switches that facilitate sharing.

The Appeal of Sharing

Economics, not attitude, is driving the sharing economy.

Popular accounts of the rise of the sharing economy often frame it in terms of culture or ideology. For example, millennials do not want to be trapped by expensive belongings such as houses and cars. Or sharing is good for the environment and fosters sustainability. But our consumer research shows that economics, not attitude, is driving the sharing economy.

Users enjoy value, quality, and variety. According to our survey, the principal reason consumers find sharing services useful is that they provide great economic value. The two other main advantages are that the consumer knows what he or she is getting and can trust the service because of ratings and reviews. These findings were remarkably consistent across the three countries surveyed, suggesting that the appeal of sharing is global in scope.

We also asked consumers what attracted them to the sharing economy. Variety, access to better products and services, and the ability to have a unique experience were the top three benefits cited. Reducing their carbon footprint and connecting with interesting people ranked lower.

These findings are consistent with how the market has developed. After Airbnb launched, it sought to build an inventory of quirky, distinctive properties. When it tested cookie-cutter rental apartments in some locations, it found that these markets performed poorly. A plain-vanilla offering did not fit the brand or satisfy customers’ demand for value and for a distinctive sharing experience.

Nonusers worry about convenience and trust. We also surveyed consumers who do not use sharing services. They cited three main reasons. They enjoy the convenience of ownership; they do not trust the reliability of sharing platforms that they have never used before; and they are uncomfortable sharing payment information.

These barriers are surmountable. In fact, they are precisely the reasons why early critics believed that the sharing economy would not take off. But the economic benefits of sharing, the protections offered by insurance, and the gathering trust in user reviews ultimately won consumers over. Among those who use sharing services, 57% of US survey respondents, 67% of Indian respondents, and 40% of German respondents said that well-priced, convenient offers could cause them to give up ownership altogether.

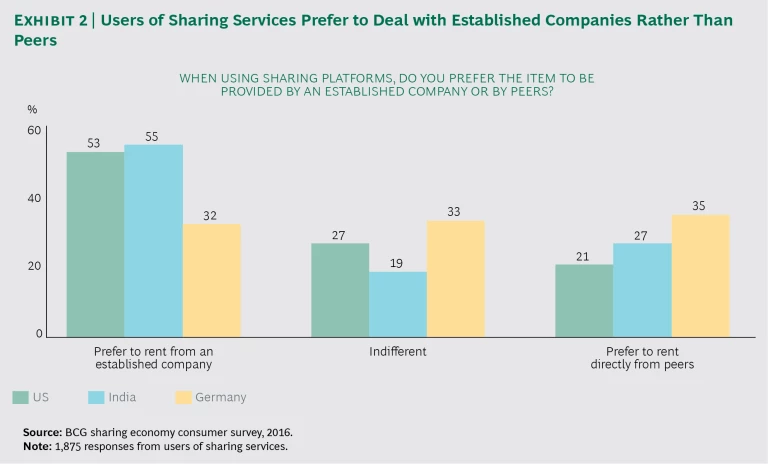

Sharing is not just for startups. Despite their early lead, startups do not have a lock on the sharing market. In fact, consumers in India and the US would prefer to engage in sharing with professional or established companies. In the US, 53% of our respondents said they would prefer dealing with these operators, compared with 27% who said they were indifferent and 21% who would prefer dealing directly with peers. The preference for professional operators is even greater in India. (See Exhibit 2.) This preference reflects the desire of consumers for certainty, consistency, quality, and transparency. The market is open to both startups and established companies that can offer these benefits.

What’s Left to Share

The sharing economy looks to be a land of leviathans. Airbnb and Uber have the most visibility and financial heft. These two companies have collected more than half of the $23 billion raised in venture funding since 2007, but many other companies, such as Lyft in the US, Didi Chuxing (formerly Didi Kuaidi) in China, and Ola in India, are rapidly gaining market share and leadership.

Beneath the surface, there is even more activity. While ride sharing and accommodations are the two hottest areas for venture funding, investors are also funneling money into asset sharing in areas far removed from rides and rooms. (See Exhibit 3.) Startups offering shared workspaces, storage, delivery, and logistics platforms rank third, with nearly $2 billion in funding, followed by vehicle sharing, with nearly $810 million in funding, and fashion with more than $240 million.

Consumers have already spoken. They appreciate the convenience, variety, and cost-effectiveness of sharing. The economic and business rationale for sharing is strong, both for startups and for incumbents. Companies should be exploring their options in this new world of declining transaction costs and rising consumer interest in sharing. If they don’t, their competitors almost certainly will.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.