Small brands are stealing share from big brands. Consumers are applying Caudalie skin cream after their morning shower, drinking Peet’s coffee and eating Chobani yogurt at breakfast, visiting Pret A Manger for lunch, and winding down in the evening with a Ballast Point craft beer.

Conventional wisdom says that today’s consumers want healthy, natural food and personal-care options, and millennials, in particular, prefer authentic to mass-produced goods. To win back this new breed of consumer, the thinking goes, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies have few options. Either they can launch small brands, at the risk of fragmenting attention and resources, or they can try to increase earnings through deep cost cutting, emulating the approach the private equity firm 3G Capital has taken in its acquisitions of large consumer brands. In short, many believe organic growth from the core is over.

We disagree. Goliath can defeat David. Consumers’ tastes have changed, but their underlying needs and desires have not. What has fundamentally changed is the economics of supply. Scale was once all important. On its own, however, it no longer guarantees competitive advantage. Even so, large FMCG companies can prevail over their supposedly nimbler foes. But they need a new playbook.

What has fundamentally changed is the economics of supply.

First, they must master the new science of consumer demand. This is foundational to uncovering the unmet needs that small brands are satisfying better and to constructing a stronger, mutually reinforcing portfolio of brands. We are surprised how few FMCG companies have harnessed the latest advances in this area.

Second, they need to engage with consumers in new ways, accelerating adoption of the viral, personalized, and experience- based methods that small brands have exploited.

Third, rather than fearing the complexity that comes with creating and marketing a wider variety of brands and products, they need to embrace it strategically. In a fragmenting world, the ability to serve a wide range of demand effectively and efficiently can be a competitive advantage.

Finally, they need to emulate the focus, coordination, and speed of their upstart rivals. Those companies rely on the agile principles, popular in entrepreneurial hubs around the world, of rapid prototyping, testing, and learning in continual cycles.

This is an ambitious agenda for large FMCG companies. But failure to act is the first step on a slow journey to irrelevance.

Why David Is Winning

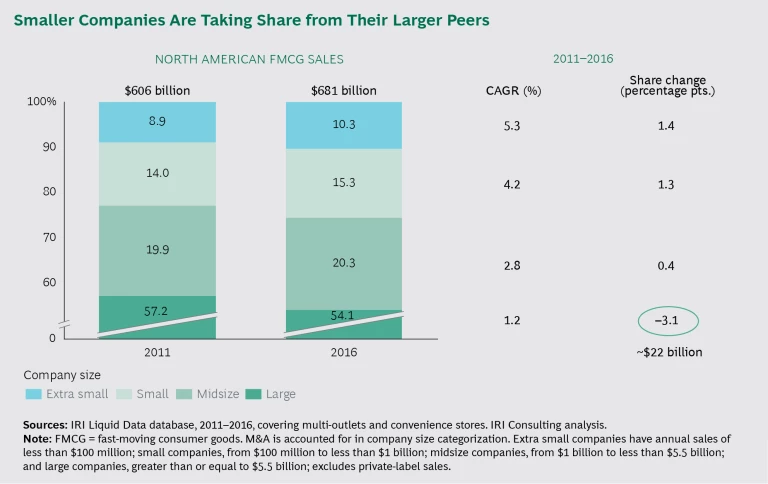

For the past five decades or more, multinational FMCG companies strengthened their brands, expanded their portfolios, steadily increased share and revenues, and created strong shareholder value. It was an era of big media, big retailers, and big brands. But about five years ago, smaller companies and brands began to take share from their much larger rivals for the first time. In North America, about $22 billion in industry sales shifted from large to smaller companies from 2011 to 2016. (See the exhibit.) Europe has experienced a similar shift. What’s behind this change?

While startups as a group appear to have understood demand better than larger companies have, they could not have succeeded to this degree without fundamental changes in the economics of supply.

In short, today’s Davids have better slingshots. Outsourced production lets them “rent” manufacturing scale. New distribution channels offer easier market access at small volumes, and social media channels allow them to build brands at lower fixed cost. Upstarts are finding their way into stores, homes, and consumer consciousness as never before. Let’s unpack what is driving their success, and what is not.

Consumer Demand

The belief that consumers’ preferences have shifted is understandable but misplaced. On the basis of our research in this area and our work over the past five years with global FMCG companies competing against smaller rivals in more than 20 categories, we have concluded that the fundamental drivers of consumer demand have remained consistent over time.

The belief that consumers' preferences have shifted is understandable but misplaced.

People have core needs and desires: They want to indulge or energize. They want to wind down and relax. And many want healthy food and beverages. These are not new needs. What’s new is the ability of startups to tap profitably into underserved needs. Consider the growth of energy drinks. Consumers have always been drawn to beverages that deliver quick energy—coffee, tea, or cola anyone? And none of us is more tired. In fact, Americans sleep more today than they did in 1990.

Red Bull, Monster, and Rockstar didn’t find a new need. They had a great idea for how to fulfill an old one, and the changing economics of supply made it possible for them to turn that idea into a successful business.

Supply Economics

During the 50-year rule of big media, big retailers, and big brands, the FMCG playbook focused on scale in order to reduce unit costs in sourcing, manufacturing, brand marketing, trade spending, and overhead. Lower costs allowed companies to invest in innovation, key account management, and global functions, thus reinforcing their advantage over smaller players.

Scale created superior economics and barriers to entry, but those advantages are now eroding. Small companies are increasingly able to access or even surpass the economics of much larger competitors in four key areas.

Asset-Light Production. Small FMCG companies no longer need to own the means of production; they can effectively rent scale from a large comanufacturer. Through outsourcing, smaller companies can trade massive capital spending for more manageable variable costs at low volumes.

Originally a French baked goods company, Michel et Augustin has expanded into drinkable yogurts by buying or leasing excess factory capacity. The factory owner achieves scale, and Michel et Augustin is able to focus on merchandising and sales. The company grew 26% annually from 2008 through 2015.

Expanded Distribution Options. Small FMCG companies used to be stymied by a limited number of big retailers that carried a limited number of brands, plus their own private labels. Today, they find willing customers in fast-growing new retail formats, especially premium, convenience, and online. In the brick-and-mortar world, Whole Foods in the US, Canada, and the UK carries small brands of natural, organic, and convenient-snacking items. In France, retailers Biocoop and Naturalia carry a similar line of products. At Amazon and other online stores, shelf space is unlimited: small brands often have the same visibility as large ones.

Some of these new channels offer small FMCG companies access to marketing and commercial tools and insights that were once the exclusive preserve of their larger peers. Amazon, for example, offers sophisticated marketing and consumer insight services, product sponsorship opportunities, and pay-as-you-go computing resources that can help even single-brand companies find their target consumers.

Variable-Cost Marketing. Social and digital media have given small companies the opportunity to build their brands and attract new customers without large upfront commitments to media spending. Unlike global consumer brands, smaller companies are not necessarily trying to reach a mass audience through paid media, such as TV advertising. Rather, they are trying to make personal and targeted connections, which social and digital media facilitate with variable-cost marketing.

Ease of Coordination. The small attackers can often act more quickly and creatively than global companies in bringing brands to life. As founder-led companies, they are focused and efficient and do not bear the coordination and governance costs of large organizations. Their agility and simplicity allow them to outmaneuver large, siloed FMCG companies.

How Goliath Can Spring Back to Life

David may have won a few battles, but Goliath is still Goliath. Large FMCG companies must go back to their roots and rediscover what made them great in the first place—understanding their customers’ needs, creating products that meet those needs, and building brand engagement. In the process, they will need to learn to manage complexity rather than eliminate it and to break down functional silos, which stand in the way of agility and speed. These are not new goals, but—given the new competitive dynamics—the urgency to achieve them has never been greater. Doing so requires coordinated action on four fronts.

Upgrade from Consumer Research to Demand Science

Large FMCG companies typically oversee multiple brands and brand extensions. And too often, the benefits from growth in one product are offset by cannibalization elsewhere in the portfolio. It doesn’t need to be that way, but avoiding this requires a shift in the way companies think about market segmentation.

Traditional consumer research is too blunt an instrument to maximize growth across the portfolio. It assumes that consumers can be divided into meaningful segments based on demographics, attitudes, or usage levels, so it leads to questions like, “Let’s understand the needs of millennial Hispanics.” This assumes all millennial Hispanics have similar needs and that those needs are the same on Tuesday morning as they are on Saturday night.

Traditional consumer research is too blunt an instrument to maximize growth across the portfolio.

A methodology we call demand-centric growth (DCG) segments demand, rather than consumers. DCG does not start with assumptions about how to segment the market—it derives the segmentation analytically. The process yields a set of “demand spaces,” or segments of demand, that comprise distinct sets of targetable consumer needs. These demand spaces can be defined by multiple factors, such as setting—day, time, whether the consumer is home alone or out with friends—as well as ethnicity, gender, age, and attitude. A rigorous, analytical model determines which variables best predict needs and choice.

For each demand space, DCG also generates insights into the key drivers of demand and what it takes to capture it. The data is clear: within a demand space, the brands that best satisfy the critical consumer needs outperform the alternatives in the market.

The insights derived from DCG can reignite growth. Consider a leading snack food company seeking to grow. The company had huge amounts of data on how people with different demographic backgrounds, attitudinal profiles, or consumption patterns view their own and their rivals’ products. It finely parsed differences in how consumers purchase particular categories of food. Despite those efforts, it struggled to unlock consumer demand and to win in the fastest-growing channels. As a result, the company’s main brands were losing share to smaller brands, and new launches were cannibalizing existing products.

DCG analysis revealed nine unique demand spaces, which were based on context rather than ethnicity, age, or usage patterns. The company targeted each of its brands at a specific demand space. The laser focus on needs drove brand growth, and the separation of brands into different demand spaces limited cannibalization. The snack maker turned around years of stagnation. Volume increased by 3% annually over several years, market share grew materially, and market value rose by more than $3 billion.

Reinvent Consumer Engagement

The shift from the era of big retail and big media calls for new consumer engagement models. Historically, in pursuit of scale, most brands maximized their consumer reach, often at the expense of the richness of communication and consumer activation. Digital tools and big data are now breaking the tradeoff between reach and richness by enabling affordable and effective personalized connections at scale.

Many FMCG companies have already embarked on digital transformations centered around precision advertising, customization, and viral marketing. While these new capabilities are valuable—they can increase the efficiency and effectiveness of media spending by as much as 40%—they are unlikely to create enduring competitive advantages.

As a next step, companies should strive to connect individually with each of their millions of customers. Big data and artificial intelligence (AI) are bringing us closer to the Holy Grail of “segment of one” marketing. Advanced retailers have already built personalization capabilities that enable them to adapt messages to hundreds of thousands of consumer segments.

Data is the spark that ignites customization, and large companies have an easier time than small ones in collecting and aggregating large data sets. They have natural scale advantages over smaller peers and the ability to generate proprietary data through multiple content, e-commerce, and customer relationship channels. Kraft, for example, generates consumer insights from chocolate and dessert lovers through Kraftrecipes.com, while Danone generates rich data from pregnant women and young mothers, a key segment, through its online sites. Smaller companies have to source data from Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other third parties at a higher cost, and the insights are often less relevant.

L’Oréal, the world’s largest cosmetics company, is developing relationships with millions of customers through a wide range of digital activities. More than 20 million people, for example, have downloaded L’Oréal’s MakeupGenius. This app lets consumers “try on” cosmetics by converting an iPhone screen into a virtual mirror—and generates individual profiles. L’Oréal’s partnership with the startup platform Founders Factory has facilitated investments in digital startups such as insitU, which creates personalized natural skin care.

These new approaches enable L’Oréal to sell directly to consumers, drive traffic to stores (and thereby increase its value to retailers), quickly test new products or content, and gain insights from a large consumer base in real time.

Developing personalized connections at scale is not easy. It requires a transformation of the marketing function and new ways of working. L’Oréal, for example, has hired 1,600 digital experts; 14,000 other employees have received digital training.

Developing personalized connections at scale is not easy.

Embrace Value-Added Complexity

In a fragmenting world, niche brands targeted at attractive demand spaces trump megabrands that seek to be all things to most people. But for large FMCG companies, addressing multiple targets with multiple brands and products necessarily introduces complexity to product and channel strategies. A rigorous demand-centric approach can help separate the complexity that creates value from the complexity that creates cost, inefficiency, and loss of focus. Such an approach depends on two factors.

Segmenting the Long Tail. Traditional FMCG companies often try to eliminate low-volume brands in order to focus on bestsellers. But in today’s fragmented world, that approach can be a growth killer. Demand-centric insights can help companies identify which of their smaller brands, if properly repositioned, enhanced, and extended, have growth headroom. In our experience, many small brands have an avid following that can be expanded by more clearly targeting them at attractive demand spaces. For these, added complexity is worthwhile. Brands lacking demand headroom are candidates for complexity reduction or divestiture.

Reducing Product Complexity Without Lowering Variety. Long tail thinking applies not only to brands but also to variations within brands. Variety of size, flavor, and quantity can increase customer loyalty and sales. But companies often launch product variations without fully understanding the effect on complexity and costs or the value to customers.

Understanding the difference between beneficial diversity and wasteful complexity can help global FMCG companies capture profitable pockets of growth and avoid cash sinkholes. Through careful DCG analysis, companies can determine precisely which product attributes consumers value and then diversify products just enough to satisfy those desires. They can also use supply chain insights to standardize the most costly product components. As a result, companies can decrease the complexity of their product portfolio while still satisfying consumers’ desire for variety.

This combination of market and supply chain insights lets companies identify “platforms” that hit a sweet spot of value and cost. These platforms can be the basis for offerings that serve new customer needs, price points, channels, or regions with minimal additional complexity.

A food manufacturer used this approach to address complexity in its biscuit portfolio. The company produced biscuits of many diameters even though, research showed, consumers did not value this variety. It had also let complexity creep into raw material procurement and packaging design. The manufacturer subsequently reduced the number of product specifications by nearly 60% while reducing the number of SKUs by only 15%. This lowered COGS by 4% to 7% and increased sales by as much as 2%. It also freed up resources that could be directed toward new products that would address other attractive pockets of demand.

Reshape Your Organizational DNA

The organizations of most large FMCG companies are built to take advantage of global scale, efficiency, and control. They tend to have rigid functional siloes, bureaucratic hierarchies and processes, and complex matrices. As a consequence, decision making is often slow and far removed from actual customer concerns, cooperation is weak, and employee engagement is low.

This is not a recipe for success when competing against entrepreneurial FMCG companies that are sharply focused on a relatively narrow product portfolio and set of markets. In most cases, the founders are still in charge. They are able to convey their vision, goals, and passion directly to their teams and to receive continual feedback from the floor and the field.

These competitors also have fluid and dynamic organizations. Instead of being governed by functional silos, rigid hierarchies, and cumbersome processes, they move people where the work is and constantly adapt to changes in priorities and in the world around them.

Large FMCG companies cannot shrink to match the organizational strengths of their young competitors. But they can make fundamental changes to process, structure, and ways of working that free them to compete more effectively.

Large FMCG companies cannot shrink to match the organizational strengths of their young competitors. But they can make fundamental changes that free them to compete more effectively.

In particular, large FMCG companies can embrace the agile principles that govern many smaller companies. Agile teams are fast, cross-functional, experimental, and self-directed. They are run by a product “owner,” who is in charge of ensuring that the consumer remains at the center of key decisions. The teams operate in a “test and learn” culture of iteration and frequent feedback—and once they find a winning formula, their cross-functional alignment enables them to scale it rapidly. These practices, which originated in software development, can be applied to companies as diverse as banks and airlines.

Large FMCG companies are also experimenting with agile approaches. Marketing organizations, for example, are starting to break down product-based silos and deploy resources dynamically across the portfolio. This approach requires new ways of managing people and career paths. One company, for example, puts newly hired assistant brand managers through a two-year training curriculum that exposes them to multiple projects, which are selected on the basis of the organization’s strategic goals and the employee’s skills and development objectives.

At another FMCG company, marketing and sales had trouble communicating because they were in different parts of the organization: marketing sat in a global business unit, while sales was part of the regional business. The company created end-to-end country brand teams with members from marketing, sales, and traditional support functions, such as supply chain, HR, finance, and R&D. This setup put key decision makers in the room together and placed decision making closer to customers.

Organizational shifts like these pay multiple dividends. By becoming more agile and experimental, companies will not only grow faster but also be more attractive to top talent, and in many cases their more streamlined organizational model will deliver cost benefits as well.

Many industry commentators and analysts suggest that the advantages of legacy and scale are fading and that large FMCG companies are facing a long, slow, and painful war of attrition. We disagree. The game is not permanently tilted in favor of smaller companies. But large FMCG companies need a new playbook to prosper in today’s strategic environment. The four-part agenda outlined above is big and ambitious. The companies that choose to pursue it will be rewarded with competitive advantage and growth.