This is the last of three articles on the sharing economy. The first article looked at opportunities created by the sharing economy and shed light on consumer attitudes toward sharing derived from extensive market research conducted in Germany, India, and the US. The second article examined companies’ strategic options for turning potential threats posed by the sharing economy into a strategic advantage. This article focuses on the future of sharing in the global economy and the specific business models that are likely to succeed.

T he sharing economy has rapidly emerged as a large and expanding force. At first glance, it seems mainly limited to the mobility industry (Uber and China’s Didi Chuxing) and the hospitality industry (Airbnb). But the economic foundations of sharing are broad. Many other industries could soon face the disruption experienced by taxi fleets and hotel chains—as the emergence of Boatbound (leisure boat rental), PeerBy (neighborhood exchange of household items), and Vrumi (rooms rented out as office space) illustrates.

The sharing economy is powered by declining transaction costs. Smartphones, internet connectivity, and the cloud allow consumers to efficiently search for their desired goods and services, understand the terms, ensure timely logistics, and enforce the agreed-upon contract. Formerly frustrating transactions have become hassle-free.

Ride-sharing and short-term lodging rentals emerged on the bleeding edge of the sharing economy because consumers were already accustomed to calling cabs and booking hotel rooms. But consumer behavior can likewise change when the economics, convenience, and variety afforded by new ways of conducting ordinary activities are sufficiently compelling.

Let’s look at how the sharing economy may evolve.

The Power of Declining Transaction Costs

In India and Dubai, RentSher connects consumers who want to rent household goods—baby carriages and party supplies, such as tents and speaker systems, are popular items—with people who want to earn extra income from unused items that they own. The service eliminates the inconveniences of traditional leasing, such as the need to arrange for pickup and delivery, and reduces the transaction costs that prevent two parties from finding one another, negotiating, and closing a deal. Taking advantage of abundant local labor, RentSher sends teams into the field to photograph and list goods on behalf of owners and transport them to renters. This turnkey support helps both asset owners and potential renters become comfortable using the platform.

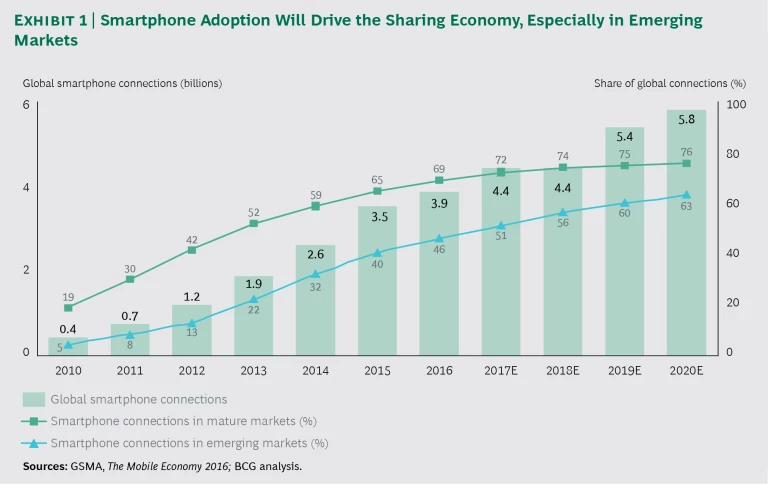

The RentSher approach highlights two critical developments that have implications for transaction costs and the future of the sharing economy. First, smartphone penetration is rising sharply, especially in emerging markets, providing a strong launch pad for sharing services. More than half of all mobile connections currently involve a smartphone in those markets, and the share will approach two-thirds within just a few years. This growing foundation will enable and encourage innovations related to the sharing economy for newly accessible consumer groups. (See Exhibit 1.)

Second, transaction costs will continue to decrease as even more friction is removed from sharing platforms. RentSher solved the hassles of listing and logistics by relying on local labor. Consider how the following developments will play a similar role in all markets:

- Matchmaking. Sensing, connectivity, and data are merging into a single system. As our colleague Philip Evans envisions in “Borges’ Map: Navigating a World of Digital Disruption,” “Every person and object of interest is connected to every other.” In this not-too-distant world, potential renters will have an instantaneous view of the availability and condition of shareable goods because they will all have an online presence. In this connected and frictionless world, intermediaries and matchmaking will decline because buyers and sellers will interact directly.

- Logistics. As self-driving cars, drones, and delivery robots come online, the effort and expense of transferring goods will fall and the potential market for shareable goods will expand geographically.

- Enforcement. Blockchain, “smart contracts,” and other code innovations that regulate payment, enforcement, and terms and conditions are rapidly maturing. A blockchain—a sort of distributed ledger—can help document asset provenance, usage history, and identity. The Ethereum blockchain—one of several competing ledgers—supports smart contracts that automatically release the payment when certain conditions are met.

With the decline in transaction costs, many goods now owned by consumers and companies could become largely rental items.

Developing Trends

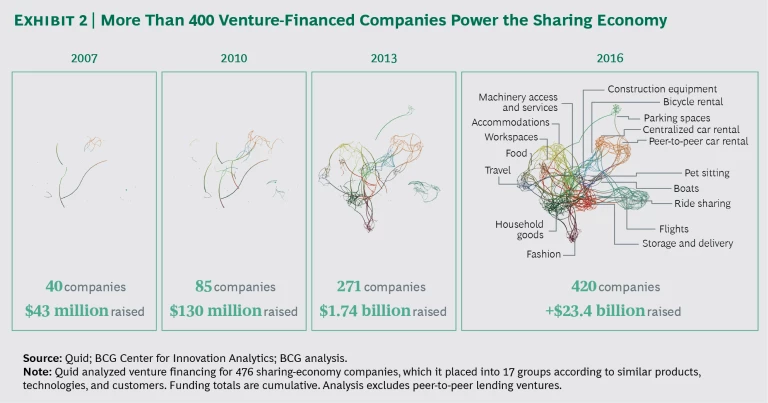

Entrepreneurs and inventors are still exploring the reaches of the sharing economy. We identified 17 groups of sharing startups that have received sizable amounts of venture funding since 2007. (See Exhibit 2.)

A few trends seem clear. First, within the B2C market, sharing has definitively moved beyond rides and rooms. Startups offering shared workspaces, storage and delivery, and logistics (a category that includes pet sitting and parking spaces) are the third most popular targets of venture funding. Companies in this group, including WeWork and Vrumi, have received nearly $2 billion in investments. Vehicle sharing, which includes peer-to-peer car rentals, centralized car rentals, and bicycle rentals, is the fourth most active group, with nearly $810 billion in investments.

The second trend is the expansion of investment activity into the B2B market, with approximately $150 million invested in new startup ventures, such as the construction-equipment rental business Yard Club. Few industries are immune to falling transaction costs and the rise of sharing-economy business models. Executives across industries should be thinking about how these developments might alter their industry’s exposure and affect their own strategic options.

Shaping the Future of Consumer Behavior and Product Design

To expand further, the sharing economy must make not just economic sense but also common sense. For products with emotional associations or long histories of ownership, the move toward sharing may be slow or never happen at all. It’s hard to imagine, for example, an active sharing market for engagement rings or dogs and cats. (Pet care is another matter, as the service Rover.com has shown.)

Usage Patterns. In the case of products for which ownership has been out of reach for many users, sharing is likely to find fertile ground. For this reason (as discussed in our second article), emerging markets are especially promising targets for the sharing economy. In India, for example, 93% of respondents to our survey—most of whom live in urban areas and are well educated—said they had used Ola Cabs, and 81% had used Uber, higher participation rates than in the US or Germany.

Many consumers in these markets have only recently started to have some disposable income, so their buying and ownership patterns are not firmly set. They are willing to rent certain items—such as household appliances (India’s Rentomojo)—that might be surprising to mature-market consumers. Similarly, emerging markets are experiencing growth in motorbike taxis (Rwanda’s SafeMotos) and car pools (Nigeria’s GoMyWay), neither of which would be likely to take hold in mature markets.

Product Design. Sharing has the potential to reshape product design. Take vehicles. Where an active car- and ride-sharing market develops, consumers no longer have to compromise with a vehicle that serves many needs imperfectly. Minivans, for example, are often used for hauling children and gear, commuting to work, and going out for an evening without the kids. But they are not necessarily the best choice for anything other than family trips and transporting children from place to place. With sharing a viable option, the family car can instead be a sedan. When adults have car pool duty, they can rent a minivan. When they need to haul gear, they can rent a pickup truck. For romantic getaways, they can rent a sports car. Products that represent a compromise among multiple functions—like the minivan, crossover bicycle, or sit-on-top kayak—may fall out of favor, while niche products gain in popularity.

Sharing has the potential to reshape product design.

Everything as a Service

The rise of the sharing economy is not happening in a vacuum. In the broader economy, nontraditional “rental” arrangements are also gaining traction. Consumers increasingly are renting music via streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music. In 2016, record labels earned more US revenues from these services than from the sale of CDs and albums. In computing, the cloud allows companies and consumers to access software, storage, and other resources as a service. They pay only for what they use and avoid the capital costs of ownership. As with sharing, lower transaction costs (including faster download speeds) have facilitated this shift to service and subscription models in music and software.

Could the current sharing economy be just an intermediate phase between a past of traditional ownership and a future of everything as a service (XaaS)?

Sharing is conceivably capable of replacing not just traditional rentals but ownership of a wide range of goods as well. If Rent the Runway and Rentez-Vous reach scale, for example, consumers may become less willing to buy clothes for special occasions. Boat owners could decide that it’s easier and less costly to rent from Boatbound ten times a year than to buy and maintain a pleasure craft that spends 355 days a year in dry dock or the garage.

The sharing economy is still relatively young and undeveloped. Most sharing businesses are still at the beginning of the S curve, and the technological possibilities and consumer dynamics of sharing are still maturing. Executives should not assume that sharing tomorrow will be the same as sharing today, any more than traditional rental businesses foreshadowed the modern sharing economy. Still, it’s not too early to imagine how falling transaction costs, XaaS business models, and changing consumer preferences about ownership will alter strategy and business models. Executives should be staying ahead of these changes and shaping the future of sharing in order to take advantage of the opportunities—and deal with the potential competitive challenges—that sharing will bring.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.