Diners have a new definition of convenience, and restaurants need to respond.

Convenience has long been a driving force in the restaurant business—and historically, the most widespread brands with the best-situated locations held an advantage. No longer. From the consumer’s point of view, thanks to the rapid rise of digitally enabled food delivery, convenience is no longer a matter of location. Internet-based delivery services and restaurant meal aggregators are rewriting the restaurant rulebook as they bring convenience to the customer’s front door at the click of a mouse or the tap of a smartphone screen. Digitally enabled delivery allows consumers to access any type of food for any occasion—on demand.

Potentially even more disruptive, though, is a parallel shift in diners’ expectations. As digital ordering and delivery have become mainstream, new (and a few incumbent) players are reconditioning consumers and redefining the market. Consumers are coming to expect new levels of ease and near-total transparency in the process of ordering, receiving delivery, and providing feedback—regardless of whether they are interacting with a restaurant brand or a third party. Meanwhile, brands are losing access to their customers and their customers’ dining decision-making.

The restaurant value chain is up for grabs. The restaurant brands—or third parties—that provide the easiest, most transparent experience across a range of needs or demands will likely own the consumer. Those that can master the “last-mile” economics at scale will have a huge advantage in physical delivery. When the industry reaches a new equilibrium, in which ease and convenience play an even greater role than they do today, brands must offer consumers a compelling value proposition, rooted in the needs that drive diners’ choices.

We are still in the early days of this upheaval, but three things are already clear:

- Consumers’ demand for convenience and their rising expectations for ease and transparency will continue to fuel food delivery, producing what is likely to be the most substantial market disruption ever in the restaurant industry.

- The disruption has profound implications for brands, regardless of whether and how they choose to participate in delivery.

- Every company needs to develop a responsive strategy now or face the likelihood of enduring stagnating sales and market share as the delivery trend accelerates.

Delivery Is Here to Stay

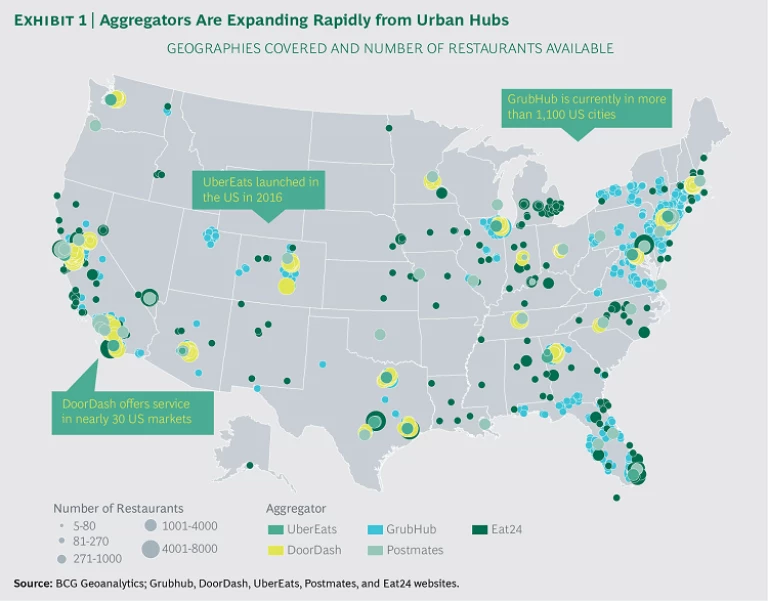

The restaurant delivery market, though still small, is growing quickly. Restaurant delivery sales in the US have seen double-digit annual growth over the past three to five years, reaching an estimated $25 billion to $30 billion in 2016 and accounting for about 5% of the total restaurant market. Once the purview of city dwellers, delivery now enjoys broader geographic and demographic appeal. (See Exhibit 1.) Recent BCG research found that more than 40% of restaurant users order delivery at least once a month. Almost half of all restaurant delivery orders today come from mobile or online channels.

At current growth rates, total delivery could make up 7% to 8% of restaurant sales by 2020, with digital ordering representing 4% to 5% of all sales. But if growth accelerates, digital delivery may reach 10% penetration or higher, based on what we have seen in other business sectors, such as travel, which could bring total delivery up to 12% or more of US restaurant sales—a sum approaching $75 billion annually.

Historically, restaurant delivery has served a narrow and well-defined set of occasions. About 70% of delivery meals replace a meal (usually dinner) that the buyer would otherwise have made at home. Delivery has been overindexed in several consumer need states, including fill me up and relax. (For a description of need states in the dining business, see Casual Dining: How Brands Can Pivot from Irrelevance to Growth , BCG Focus, November 2014.) In the past, high barriers to entry, such as significant startup and operating costs, limited delivery at scale to a few brands (and cuisine types) that managed to carve out protected market positions. Large quick-service restaurant (QSR) pizza brands are the leading example.

The emergence of third-party digital aggregators, which are quickly gaining scale, is accelerating the rise of delivery and generating new types of demand. Aggregators hold only about a 15% share of total delivery sales in the US market today, but total sales through aggregator platforms have grown at a rate of 50% annually since 2010, and growth is projected to continue at about 30% a year through 2020. Aggregators don’t simply replace going out to eat with ordering in. They engage consumers for new occasions. As is the case with traditional delivery, aggregators’ business skews toward dinner occasions; but orders placed through aggregators also generate higher volumes at lunch, thanks in part to the range of meal options, portion sizes, and cuisines available. And although orders placed through aggregators skew toward the relax need state—as they do with traditional delivery—we are seeing a higher share in the satisfy a craving need state.

Aggregators offer multiple benefits to brands, especially small and medium-size brands. For one thing, aggregator users tend to be more valuable customers: they purchase about seven meals per month at restaurants compared with an average of about three per month for nonaggregator users. For another, delivery users in general—and aggregator users in particular—tend to be young. Our research shows that Millennial consumers account for about 45% of delivery orders and 55% of aggregator orders, as opposed to 30% of all restaurant purchases. Having access to Millennials through aggregator orders helps brands open a channel for greater engagement with this important consumer segment.

For smaller brands, presence on an aggregator platform provides much greater reach than the brand can achieve on its own, as well as a new channel for raising consumer awareness of its offerings. For example, almost half of all US restaurant users are aware of GrubHub, the largest aggregator, which puts GrubHub on a par with many medium-size or regional brands. (Einstein Bagels has national awareness among restaurant users of 52%; Qdoba, 49%; and Shake Shack, 38%.)

A New Phenomenon Starts to Take Shape

Digital delivery is in an early and turbulent stage of development, with substantial startup and consolidation activity. There are more than 50 recognized digital food delivery providers in the US, but the top two—GrubHub and Yelp Eat24—hold 65% of the market.

Aggregators follow two primary models: partner and delivery runner. Some aggregators, such as GrubHub, partner with restaurant companies, often linking with the brand’s point-of-sale (POS) systems for relatively seamless order transfers. Not all of these companies provide a delivery network (in which case delivery is up to the restaurant); some serve only as an order platform. Under the delivery runner model, the aggregator’s system does not link with the brand’s POS systems; instead, consumers place orders through the runner’s platform, and the aggregator dispatches the orders to a delivery runner in the field. The runner places each order at the appropriate restaurant, picks it up, and delivers it to the customer. Examples of this type of aggregator include Favor and DoorDash.

Both models have demonstrated substantial success at engaging brands in the delivery business. In a recent BCG study of national QSR and fast casual (FC) brands, 70% of individual restaurant franchisees reported that their stores offered delivery through an aggregator. Beyond national brands, aggregators are bringing smaller regional and independent brands into the competitive set as well. Our research indicates that about 45% of orders placed through an aggregator go to small or independent brands.

Aggregators build scale for brands in two ways. First, without a significant incremental investment in labor, they can offer delivery at scale; this is their original value proposition. Second, some aggregators are building capabilities to offer brands digital marketing services, using the significant quantities of customer data at their disposal to bring a more personalized experience to the customer—and to give their brand partners better targeted marketing. GrubHub is leading the way in digital marketing today, but we believe that this is likely to be the next wave of differentiation in the segment as a whole.

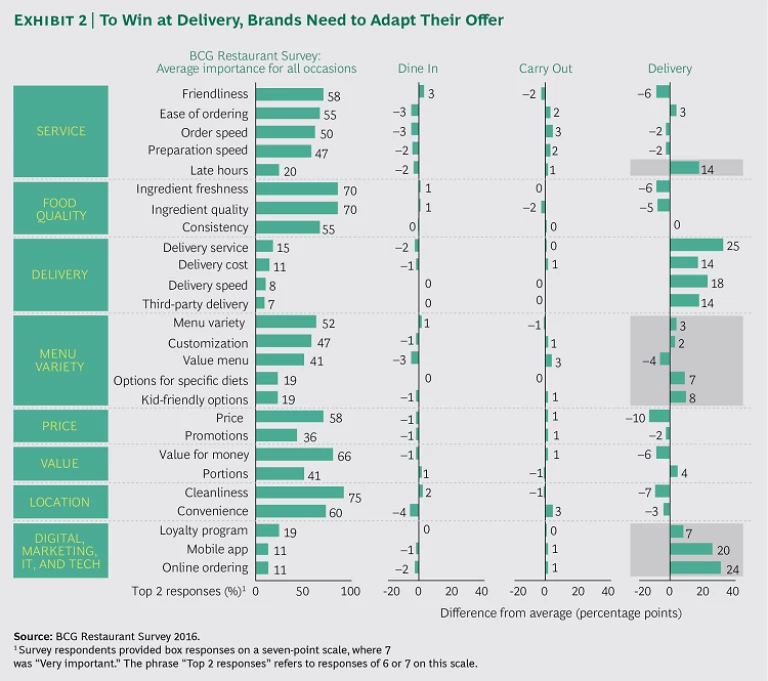

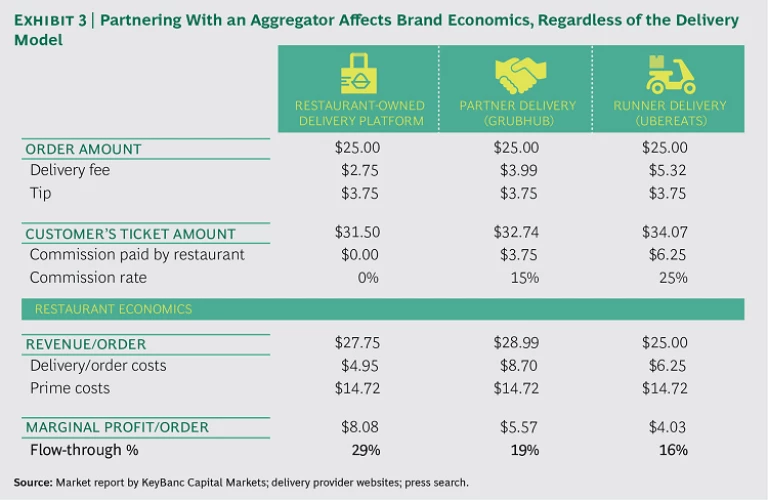

These benefits can come at a cost, however. As aggregators gain scale, they erode restaurant brands’ competitive advantages in multiple areas (such as their control over customer experience and their ability to capture customer data.) They pass significant costs back to the brand, too. The marginal profit on an order placed through an aggregator can be as much as 50% lower than the corresponding profit on a delivery platform managed by the brand. And the emergence of aggregators introduces new pressures on brands to meet consumer expectations that may differ significantly from those in the traditional dining business. For example, digital delivery customers place greater importance on menu variety and customization, late-night hours, and the mobile or online experience.

It is too early to declare aggregators the victors in the battle over which model will prevail with consumers. There is still plenty of turnover in the market as new digital players enter and others get swallowed up by market leaders. Many players have doubled down to build share, often offering significant discounts or incentives (such as waiving delivery fees) as they establish their presence in new markets and try to build customer loyalty.

Despite diners’ growing awareness and use of these services, aggregators have low advocacy rates—one indicator of enthusiasm—among consumers overall. On average, aggregators have a brand advocacy score of only 9% on BCG’s Brand Advocacy Index (BAI), which measures actual recommendations for and criticisms of a brand. By comparison, QSR brands have an average BAI score of 23%; and FC brands, an average of 32%. One reason for this disparity is that delivery service providers have plenty of ways to disappoint customers but relatively few ways to delight them.

Like many other new services, aggregators have quality and consistency issues to overcome. Consumers criticize aggregators for poor food condition, poor value, and long delivery times. Our research indicates that consumers’ “acceptable” delivery time window is about 20 to 30 minutes from placing the order; but aggregator delivery times are often 45 to 60 minutes, and sometimes more (although some newer players in the market, such as Amazon Prime Now Restaurant, consistently come closer to the 30-minute mark).

Beyond the customer satisfaction challenges, the economic model for delivery players is a tough nut to crack. Last-mile economics has historically been the death knell for fresh product delivery. Brands that have carved out a successful delivery business, primarily pizza, are successful in large part because of their enormous scale—nearly 60% of Domino’s sales are delivered as opposed to carried out of the store.

As digital delivery services find their roles in the evolving restaurant ecosystem, a new force is emerging: voice recognition. Amazon, Apple, and Google, among others, offer such systems. Since January 2015, voice-recognition technology and platforms have attracted more than $200 million in venture capital funding worldwide. Using devices and platforms such as Amazon’s Echo and Electra, consumers can now order a pizza with a simple voice command—no need to pick up a smartphone to access the mobile app. Voice recognition is taking ease and convenience to a new level, and more brands are building this functionality into their mobile experience. In its December 2016 investor day presentation, Starbucks unveiled plans to begin rolling out its own voice ordering system, “My Starbucks Barista,” in 2017.

In view of the need for scale and the continuing advance of technology, we are likely to see consolidation and further shifts in market share in the delivery business. Ultimately, we believe a scenario could emerge in which one or more third-party players consolidate the logistics operations as a standalone service, and restaurant brands or other third parties layer their easy-to-use consumer-facing ordering platforms onto it.

Unresolved issues notwithstanding, all signs indicate that consumers will continue to fuel the growth of delivery, making it a long-term disruptive force in the restaurant business. Some 75% of consumers today expect to maintain (45%) or increase (30%) their use of delivery during the next six months. The high adoption rate among Millennial consumers (who outnumber Baby Boomers in this market) suggests forward-looking momentum.

The Impact on Brands

The impact of digital delivery extends far beyond changing consumption patterns. Entirely new consumer expectations and behaviors will cause restaurant companies to rethink the experience they offer customers, including, critically, the integrated role of their physical and virtual assets.

Digital is blunting the benefits of physical scale, which has long been an advantage for large brands. Historically, the bar for attracting customers was not terribly high: “easy enough” or “convenient enough” sufficed—which helps explain why store location was such an important consideration. Today, digital platforms (inside and outside the dining industry) set the bar. Ease, convenience, and speed are now the price of entry in terms of consumer expectations. (See Exhibit 2.) Digital technology is influencing behavior in all phases of the consumer journey (discover, search, locate, buy, postpurchase). (See Dining and Dollars: Directing Restaurants’ Digital Investments , BCG Focus, November 2015.) Increasingly, consumers are turning to a range of digital tools—and they expect restaurants, like other service companies, to deliver end-to-end, integrated digital and real-world experiences that are on a par with those offered by the best online purveyors, such as Amazon and Netflix. Factor in the pace of change, which is faster than ever before, and brands are struggling to keep up. Digital delivery is the latest and largest challenge they face.

The rapid rise of digital delivery is also changing the nature of competition in the dining market, blurring—and in some cases, erasing—traditional lines between dining-in and dining-out occasions, and complicating the idea of what constitutes a purveyor of a dining experience. In the digital world, restaurants compete not only with other restaurants, but also with grocery retailers, meal kit curators, and on-demand delivery services. Whole Foods and Instacart have formed a delivery partnership that covers (among other things) prepared foods. Amazon Prime Now offers its members free two-hour delivery—and free one-hour delivery from restaurants—in more than a dozen cities. Favor promises to deliver anything from any store, emphatically including meals, within its designated service areas. In the past two years, it has expanded from its initial market (Austin, Texas) to more than 20 locations. (If that doesn’t sound like a lot, consider how quickly Uber and AirBnB expanded to disrupt travel and lodging.) From meal kits to prepared foods to restaurant meals, consumers have a multitude of options for any occasion—at home, on the town, or on the go. They can match their choices of where and how to dine with the specific nature of the occasion and with their immediate needs.

In response, restaurant companies (like all other retailers) need to rethink the roles of physical versus virtual assets. As more consumers engage with a brand digitally, rather than in the store, the physical store’s function shifts from consumer destination to shared-service platform that enables the brand to fill customer orders through multiple channels. Indeed, a restaurant kitchen can now function as a back-of-house resource that serves multiple brands—including the store’s dining room, meal-planning, and delivery services—from the same stock of ingredients and labor. As new models gain traction with consumers, the importance of a restaurant’s space and location may decline; and if that happens, the business may need to rethink its physical footprint, either doing more (or more differently) with its space or reducing the amount of high-rent real estate it carries on its income statements.

At the same time, building a compelling brand proposition on pillars other than the consumer’s in-store experience becomes ever more important. If brands can no longer rely on consumers’ enjoying the technical and functional benefits of the store experience, the need to establish emotional resonance, especially through digital channels, will become more critical to maintaining consumer relevance.

The Need for a Clear Strategy

Digital delivery is neither a passing fad nor a tangential trend. It is already reshaping how restaurants do business and engage with their customers. For most brands, choosing not to participate is not a viable option. At the same time, the investment required for, and the business ramifications of, entering the digital delivery game are significant. Companies need a clear strategy governing how to compete. We see a five-step game plan.

Determining How the Brand Will Participate. Brands have two primary options in deciding how to play: building an internally owned and managed delivery platform, or establishing partnerships with one or more third parties.

We believe the first approach is viable only for large-scale players (or small players whose business is already mostly delivery based). But even the biggest companies should think through several questions before committing to an internal platform:

- Can the brand’s store operations and management infrastructure manage the complexity of a delivery labor force?

- Does the company have the necessary technology platforms to manage an end-to-end delivery operation—and if not, does it have sufficient scale to spread the fixed costs of building such a platform over a wide base?

- Can the brand generate sufficient volume to benefit from economies of scale? (To operate profitably, delivery labor typically requires even more scale than in-store labor. Low delivery volumes are likely to depress operating margins, even if delivery revenue is incremental to the company’s top-line.)

- Can the brand consistently meet consumer expectations regarding delivery time?

Despite the complexity of such operations, some best-in-class brands benefit from the insourced delivery model; the big pizza brands are a long-running example. In the sandwich segment, Jimmy John’s, which now has more than 2,500 outlets, has staked out a significant competitive advantage through its tightly managed insourced delivery platform and its promise of a “freaky fast” delivery time. Panera Bread launched a delivery pilot in 2016, based on its Panera 2.0 initiative, which seeks to use technology to improve the customer experience. In the company’s second quarter 2016 earnings call, CEO Ron Shaich reported strong results from the pilot and described plans to expand delivery to 15% of its nearly 2000 stores by the end of 2016.

For most brands, however, partnership with one or more third-party aggregators is likely to be the more effective strategy. With a partnership, the restaurant brand effectively outsources much of the complexity of the delivery operation. It can also add the delivery capability without incurring the costs and risks of running an internally owned service. Nevertheless, companies need to be thoughtful about how they structure such partnerships. They must develop a solid understanding of the economics of potential partners and the impact of the delivery deal on their own operating margins and on their consumers. (See Exhibit 3.)

Other key issues include the following:

- How many aggregator or delivery platforms will the brand work with?

- To what extent will partners allow the company to control the customers’ experience—or put another way, how much control of the customer and brand experience will the company cede to the delivery partner?

- Can the brand and the partner link their mobile and online platforms?

Adapting the Product Offer and Restaurant Operations. Regardless of whether they go the internal route or the partnership route, restaurant companies will need to adapt their product offerings and store operations to meet the needs of a delivery service. For consumers, delivery occasions and need states often differ from those that drive store visits. Companies need to make sure that their menus offer sufficient variety to appeal to delivery occasions and to an expanded range of need states (importantly including craving and fill me up). They will also need to tackle questions about delivery menu availability: will they be offering all products or only a subset for delivery? Pricing is another issue: will in-store and delivery prices be the same, and will the same pricing be offered across multiple order platforms? As for delivery range, is the product offering formulated to sustain the journey? How far from the store can the company offer delivery, without compromising quality? How will delivery orders affect the restaurant’s operational flow? And what modifications to existing back-of-house processes must the restaurant introduce in order to accommodate delivery orders?

Providing a Seamless Customer Journey. Beyond looking at the delivery process itself, companies must evaluate every step in their engagement with the customer and identify and eliminate potential interruptions to a seamless journey. Factors such as speed and ease of ordering become important competitive considerations. How many steps must customers take to order the product they want? How many people or screens (on their devices) will they have to interact with along the way? How quick is the ordering process? How easy is it to get information about the product or about the store?

Brands need to make it as simple as possible for a customer to continue to say “yes,” eliminating points of friction and building a virtuous cycle to reinforce the consumer’s participation with the brand. Best-in-class brands have made major strides in using technology to eliminate impediments. For example, Starbucks generates more than 20% of its transactions on its mobile platform because the platform simplifies placing, paying for, and picking up orders. (Starbucks’ loyalty program provides an additional incentive for customers to use the app.) For most companies, such an undertaking requires a new level of integration across functions including operations, marketing, and digital, along with a willingness to look beyond the ROI of a single project to focus on the initiative’s overall impact on consumer satisfaction and retention.

Moving Toward Agile Technology. Faced with the magnitude and pace of change in the industry, brands need to adopt an even more agile approach to technology and digital development. Uncertainties over how the market will develop mean that brands need an IT stack that future platforms or partners can plug in to. Technology—and the people managing it—must adapt and evolve more quickly than ever before. Multiyear development, pilot, and rollout cycles will inevitably cause slow-moving brands to lag behind consumers’ expectations as well as behind the more agile competition.

Building a Clear, Compelling Brand Position. Finally, it is more important than ever to understand, occasion by occasion, what drives consumer choice—and in the context of such choice, to recognize which delivery occasions and need states a brand can effectively compete for. Digital delivery puts many more options at consumers’ fingertips, but research shows that customers exercise those options for only three to seven meals each month, so the competition for attention can be intense. Companies need a sharp, focused brand position with a clear brand ladder to persuade consumers that their brand—more than any other—will meet the specific needs that potential customers are experiencing on one of those occasions.

Restaurant brands may be able to take a page from the travel industry playbook. Brands there have been under pressure from aggregators for many years and have learned to fight hard to keep their brand proposition front and center with consumers and to maintain customers in their networks. For example, under its “Stop Clicking Around” campaign, Hilton Hotels offers its HHonors members discounts of up to 10%, reasoning that a discount that builds loyalty is a more cost-effective play than a commission paid to an aggregator or an online travel agent.

Delivery, including digital delivery, is here to stay. Smart restaurant companies are already climbing the curve involved in building—or partnering to offer—an end-to-end digital delivery capability. Others still have time to catch up, but they will have to move quickly to understand what drives consumer demand for delivery, occasion by occasion, and to link the brand’s value proposition to those circumstances. They will also have to double down on enhancements designed to make the customer experience easier, faster, and more convenient.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Avani Patel, Alex Halbardier, and Chloe Skibba for their help with research.