This is an excerpt from Total Societal Impact: A New Lens for Strategy .

F or decades, most companies have oriented their strategies toward maximizing total shareholder return (TSR). This focus, the thinking has been, creates high-performing companies that produce the goods and services society needs and that power economic growth around the world. According to this view, explicit efforts to address societal challenges, including those created by corporate activity, are best left to government and NGOs.

Now, however, corporate leaders are rethinking the role of business in society. Several trends are behind the shift. First, stakeholders, including employees, customers, and governments, are pressuring companies to play a more prominent role in addressing critical challenges such as economic inclusion and climate change. In particular, there is recognition that meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will not be possible without the private sector’s involvement. Second, investors are increasingly focusing on companies’ social and environmental practices as evidence mounts that performance in those areas affects returns over the long term. Third, standards are being developed for which environmental, social, and governance (commonly referred to as ESG) topics are financially material by industry, and data on company performance in these areas is becoming more available and reliable, increasing transparency and drawing more scrutiny from investors and others.

Corporate leaders are rethinking the role of business in society.

As these trends gain momentum, companies need to add a lens to strategy setting, one that considers what we call total societal impact. TSI is the total benefit to society from a company’s products, services, operations, core capabilities, and activities. (See “What Is Total Societal Impact?”) The most powerful—and most challenging—way to enhance TSI is to leverage the core business, an approach that yields scalable and sustainable initiatives. If well executed, this approach enhances TSR over the long term by reducing the risk of negative events and opening up new opportunities. In the end, such an approach allows the company to survive and thrive.

Evidence of the power of this approach is mounting. Much of the research to date has focused on demonstrating the link between a company’s overall ESG performance and its financial performance. However, CEOs tell us that it is unclear where they should put their energy. Which areas in their industry provide the best opportunities to create both societal benefits and financial returns? To help answer that question, we have gone deeper and identified the link between individual ESG topics and financials in specific industries. Our study encompassed five industries: consumer packaged goods, biopharmaceuticals, oil and gas, retail and business banking, and

For individual industries, we looked at the link between performance in specific ESG topics (such as ensuring a responsible environmental footprint or promoting equal opportunity) and market valuation multiples and margins, both contributors to

- Nonfinancial performance (as captured by the ESG metrics) was statistically significant in predicting the valuation multiples of companies in all the industries we analyzed.

- In each industry, investors rewarded the top performers in specific ESG topics with valuation multiples that were 3% to 19% higher, all else being equal, than those of the median performers in those topics.

- Top performers in certain ESG topics had margins that were up to 12.4 percentage points higher, all else being equal, than those of the median performers in those topics.

ESG data is currently the best way to quantify a company’s societal impact. However, it is important to note that ESG measures are not designed to measure a company’s TSI. In particular, ESG provides a limited window onto the largest impact of a corporation: the intrinsic societal value created by its core products or services. The ESG measures that do relate to a company’s products or services tend to focus on the incremental ways a company improves its products or makes those products more accessible. In banking, for example, ESG data is not designed to capture the full economic benefit of a bank’s lending activities—but it does track the degree to which banks are lending in underserved markets. Consequently, most of our findings relate to how companies operate their business, not to the actual product or service they create.

Still, the clear links in each industry between performance in specific ESG topics and financial performance point business leaders to opportunities to enhance both TSI and TSR. Notably, we found just two negative correlations in our analysis of 65 topics (we studied 35 topics, 10 of which applied to all four industries)—suggesting that a well-executed investment in material ESG issues does not hurt financial performance.

Of course, many companies have already developed programs that aim to address various societal issues and generate business benefits. Examples include efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, programs aimed at eradicating major diseases in developing countries, and initiatives that provide opportunities that can lift people out of poverty. But too often, the results are fragmented and lack scale. Moreover, even companies that have an effective, large-scale effort intended to increase both societal impact and TSR frequently fail to measure and communicate the results to investors, their employees, and the wider public. This diminishes the benefits to the brand, to employees, and to stock market performance that companies could realize from such efforts.

Based on extensive work with clients and numerous interviews, we have identified the key success factors for integrating TSI efforts into a company’s strategy, organization, and business model. Companies that do this well will find they can not only create value for shareholders—but also make a real difference in the world.

The Business Case for Focusing on TSI

The business community has, of course, played a role in addressing societal challenges for many decades. Companies have long run their own foundations, for instance, and have established major corporate social responsibility programs.

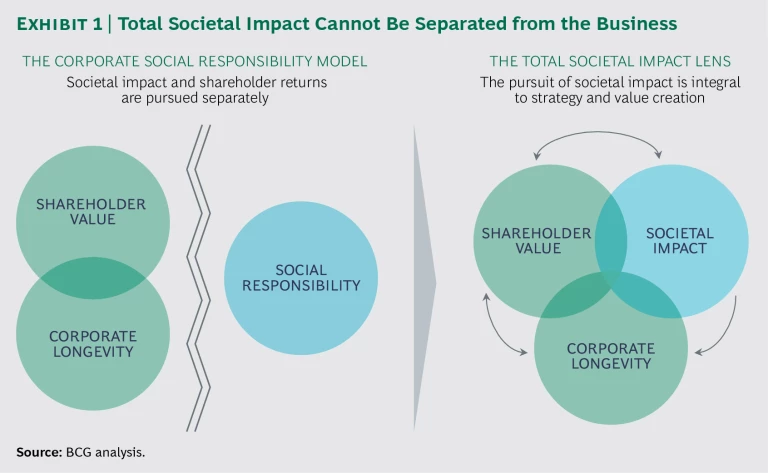

Today, it’s not enough for companies to pursue societal issues as a side activity. Instead, they must use their core business—and the scale advantages it offers—to create both positive societal impact and business benefits. The result can be a more reliable growth path, a reduced risk of negative, even cataclysmic, events, and, most likely, increased longevity. (See Exhibit 1.)

Today, it’s not enough for companies to pursue societal issues as a side activity.

BCG conducted a comprehensive study of how this approach is being adopted in five industries. In addition to our quantitative analysis and a review of external studies, we spoke with in excess of 200 people at more than 20 companies both within and outside our five industries. We also spoke with dozens of investment professionals at pension funds, foundations, sovereign wealth funds, asset managers, private equity firms, and financial advisors to understand how the investment community is assessing ESG performance and incorporating it into their decisions—and what those views mean for corporate leaders. Lastly, we spoke with international development organizations and NGOs to get their perspective on partnerships with the private sector.

The Imperative of Delivering TSI and TSR

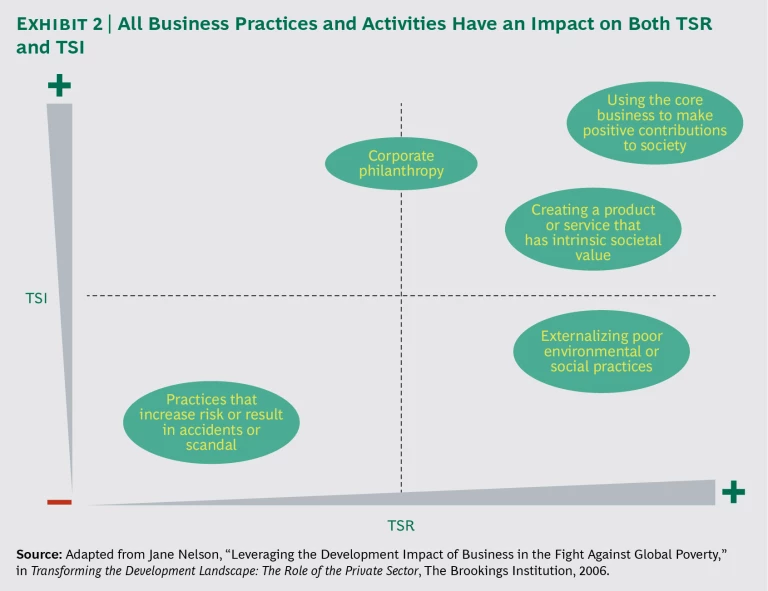

A company’s significant activities ultimately have an impact both on society and on shareholder value. Company activities are often presented in a 2x2 matrix to illustrate how much they contribute to each. Following the example of others who have conducted research in this area, we have created a matrix that shows the positive and negative impacts of business practices and activities on society and on financial performance. (See Exhibit 2.)

Assessing How Business Practices and Activities Contribute to TSI and TSR. A company’s business practices and activities ideally boost both TSR and TSI, falling in the upper-right quadrant. But placement within that quadrant—which reflects just how much these activities actually increase TSR and TSI—varies.

Philanthropy and donations, for example, can benefit society. But the impact on TSR, typically in the form of brand enhancement or employee engagement, is more variable. Some of these activities can enhance both TSI and TSR, putting them in the upper-right quadrant. But when these activities are not done well (or are done to excess), they can actually be a drag on TSR, putting them in the upper-left quadrant. A company may make donations that help society, for example, but do little to burnish its brand or engage employees.

Of course, even if companies apply a strict TSR lens, they are almost always creating some social dividends. That’s because most companies in most industries sell a core product or service—a medicine that saves lives, a household appliance that makes chores easier, or auto insurance that protects drivers against financial loss, for instance—that has intrinsic societal value. As a result, their basic operations fall into the upper-right quadrant as well.

Even if companies apply a strict TSR lens, they are almost always creating some social dividends.

The real question is how companies can identify activities that would fall farther up and to the right in that quadrant—business opportunities that generate significant shareholder returns as well as societal impact that goes well beyond the intrinsic benefit of a product or service. This requires explicitly identifying ways to leverage the core business to address social and environmental goals. How best to do so will vary by industry but can include changes to the supply chain, leveraging core capabilities of the business, and enhancements to existing products or services or the development of new ones.

Such activities can have a greater impact than most philanthropic efforts for a simple reason: they are scalable. In addition, while charitable giving can be among the first things on the chopping block in an economic downturn, a strategy built around enhancing TSI and TSR together is likely to be more sustainable because of the business benefits it aims to create.

Certainly, some activities fall in the other three quadrants, dragging down TSR, TSI, or both. For example, companies that have focused almost exclusively on delivering solid returns to shareholders have at times failed to invest in the best environmental practices or safety disciplines. However, societal expectations, regulations, and investors’ attention to social and environmental issues have evolved, making many previously permitted activities untenable.

Consequently, companies find that activities that previously boosted TSR in the short term, but had a negative impact on society, ultimately become a drag on TSR. As a result, those activities move from the lower-right quadrant to the lower left, often damaging the brand in lasting ways and even threatening the company’s survival.

The degree to which management has focused—and continues to focus—on TSR as the primary objective varies by region. In continental Europe, companies have long subscribed to the “stakeholder model,” in which employee, community, and environmental interests are all considered in addition to shareholder interests. This culture has its roots in an industrial structure dominated by family-owned enterprises and a regulatory environment for large companies that is more alert to maintaining the balance among these constituencies than in the US. In Asia, the prevalence of state-owned enterprises and family-owned, publicly listed companies creates an environment in which companies are generally focused on a broader set of objectives than simply maximizing TSR. These objectives can include, for example, supporting a country’s industrial policy.

The Trends Driving an Increased Focus on TSI. Several trends are converging that make it critical for all companies to expand their view to include both TSR and TSI.

First, companies are under mounting pressure from a range of stakeholders to play a more active role in addressing social and environmental issues such as global health challenges, climate change, and gender inequality. Employees—millennials, in particular—not only want their employers to have a greater sense of purpose but also seek an active role in companies’ societal impact efforts. In addition, customers are increasingly attuned to information related to a company’s social and environmental impact—information that can shape their buying decisions. Some governments, meanwhile, expect companies to do more to solve economic and social problems and are looking to collaborate with companies in such initiatives. The need for greater private-sector involvement in these efforts is clear: the annual gap between the cost of achieving the SDGs and the available public funding is projected to be as much as $2.5 trillion—a shortfall that many believe the private sector must largely

Second, the investment community is increasingly focused on companies’ social and environmental performance. A decade or so ago, socially responsible investing (SRI) encompassed two primary approaches. The first was negative screening, in which investors in public markets avoided stocks of companies whose products or services were deemed to have a negative impact on society. The second was impact investing, which involved relatively small investments in the private markets that would support an explicit social or environmental objective. These two approaches represented a relatively small slice of the overall investment market.

Today, however, investing with a focus on social and environmental factors is going mainstream, and investors are deploying many additional SRI strategies. Examples include thematic investing (in areas such as clean energy, education, and health care) and full ESG integration, in which managers incorporate material ESG measures into their investment models.

Investing with a focus on social and environmental factors is going mainstream.

Global figures reflect the shift. In 2016, global SRI assets hit nearly $23 trillion, accounting for more than one-quarter of total managed assets and up from $18 trillion two years earlier. The overall share of SRI investing varies quite a bit regionally. In Europe and Australia and New Zealand, roughly half of all managed assets fell into the SRI category in 2016; in Canada, the share was nearly 40%. In the US, the percentage was just over 20%, but it grew at a compound annual rate of 15% from 2014 to 2016. SRI investing has not yet taken off in Asia, where the share was close to

Asset owners and asset managers, particularly those with a long investment horizon, are paying close attention to environmental and social factors for a simple reason: evidence is mounting that company performance in ESG areas has an impact on long-term shareholder returns.

A third trend that’s moving TSI front and center is the growing availability and reliability of ever-more detailed data on company performance in ESG areas. A variety of standard-setting organizations and data vendors are behind this trend. Certainly, data challenges remain. For one thing, consensus is still emerging on which ESG topics are material for specific industries and on the appropriate ways to measure performance in those topics. And data quality and completeness need improvement. But information today is largely available and is rapidly becoming more reliable. As a result, companies will find their performance on social and environmental issues increasingly under scrutiny.

Companies will find their performance on social and environmental issues under scrutiny.

However, even if a company and many investors believe that societal and business benefits go hand in hand, several realities may make it difficult for CEOs to take this long view. These include the need to meet quarterly earnings as well as the increasing prevalence of activist investors, who may pressure the company to boost near-term shareholder returns at the expense of long-term value creation. In addition, some obstacles prevent companies from being fully rewarded by the investment community for their ESG efforts, such as the way companies and investors communicate about these issues. (See “Bridging the Investor Divide.”)

The Business Benefits of TSI

Companies that recognize these shifts and actively rethink how to improve their TSI stand to reap concrete business rewards. First, adding the TSI lens drives them to identify and address activities that will ultimately destroy TSR, activities that over time can undermine a company’s performance and ultimately even threaten its survival.

Second, the TSI lens leads companies to spot completely new opportunities—both internal and external. The most prominent include the following:

- Opening Up New Markets. A strategy that considers societal impact can give a company access to new locations and markets, and to underserved customer segments in existing markets. Partnerships—both with other private-sector players and with development organizations—often help companies penetrate these markets. Although these new markets may not be immediate money makers, entering them is often a preemptive or strategic move that leads to long-term, profitable growth opportunities.

- Spurring Innovation. Companies that adopt the TSI lens will often identify new product features or attributes that can provide societal benefits while boosting the appeal of those products. In addition, the TSI lens may lead companies to develop entirely new lower-cost products, services, and business models, all of which can open up new geographic or demographic market opportunities. These innovations, such as a new business model for an underserved community or a product that addresses a specific environmental issue, can often be successful in existing markets.

- Reducing Cost and Risk in Supply Chains. The development of more inclusive supply chains—those that draw on individuals or companies that have historically been left out—can make those networks more resilient and cost effective because they are less dependent on a few suppliers and distributors, and raw materials can be sourced closer to the end market.

- Strengthening the Brand and Supporting Premium Pricing. Companies known for products with positive environmental or social attributes, such as those that are responsibly sourced and have natural ingredients, can inspire customers’ loyalty and trust. That can translate into increased sales and even premium pricing on certain products for certain market segments, a powerful benefit in particular for the consumer goods industry.

- Gaining an Advantage in Attracting and Retaining Talent. A strong track record in contributing to society can energize the workforce and give a company an edge in the ongoing war to attract, engage, and retain talent.

- Becoming an Integral Part of the Economic and Social Fabric. Companies that explicitly work to support a country’s economic and social development goals can strengthen relationships with governments, regulators, and other influential parties.

Companies that are able to seize such opportunities while addressing potentially TSR-destroying activities increase the likelihood that they will grow and thrive over the long term. Such sustained success is increasingly difficult to achieve. BCG research has found that corporate longevity has plummeted. Public companies have a one in three chance of being delisted in the next five years, whether because of bankruptcy, liquidation, M&A, or other causes. That’s six times the delisting rate of companies 40 years ago. (See “

Die Another Day: What Leaders Can Do About the Shrinking Life Expectancy of Corporations

,” BCG Perspective, December 2015.)