During the past year, many global companies—for example, China Petroleum and Coca-Cola—have named new CEOs. In many cases, this was because shareholders or the board felt that the previous leaders did not understand the massive disruptions facing their industries. These are not isolated events. Churn within many industries, due to incessant technological change, now means that leaders are being overtaken by their competitors at an unprecedented pace.

At any one time, about one-third of large US companies are experiencing a severe, two-year decline in their ability to create shareholder value. Within that group, one-third fail to recover within the following five years. Even companies that are current industry leaders are vulnerable to disruption. And even the new leader of a top-performing company needs to watch over her shoulder for—and transform the company in anticipation of—the next disruption, for it is surely coming. In other words, if the company ain’t broke, fix it preemptively anyway.

Many new CEOs come in with a mandate to transform the company—including its strategy, business model, organization, operations, and culture. A transformation is not a series of incremental changes. Rather, it is a fundamental reboot that enables a business to achieve a dramatic, sustainable improvement in performance and alter the trajectory of its future. Because they are comprehensive by nature, transformations are complex endeavors, and the majority fall short of expectations for achieving their target value, coming in on time, or doing both. (See Transformation: Delivering and Sustaining Breakthrough Performance , BCG e-book, November 2016.)

BCG has helped companies execute more than 750 transformations, and currently, we are working with more than 150 companies on large-scale transformation programs. (Among that group, two-thirds have a new CEO in place.) We also recently conducted an extensive quantitative analysis of transformation performance among large US companies. The good news is that changing CEOs increases the odds of success. The bad news is that new CEOs—particularly those hired from outside the company—also show a wide range of success in leading transformations. This report summarizes the best practices from our direct experience and analysis and offers new CEOs an evidence-based approach for developing and implementing successful transformations.

Transformation Raises the Bar for CEOs

There are several reasons why transformations raise the bar for CEOs—especially those new to the executive position.

CEOs must continually balance short- and long-term objectives. An incoming CEO faces immediate pressure to deliver top-quartile performance in the company’s core business, in many cases, through short-term improvements. At the same time, the new CEO must reinvent the business model, enhance product and service offerings, and invest in other long-term initiatives. The best CEOs can do both.

CEOs must quickly reset investor expectations. Within six months of taking over, new CEOs need to evaluate which parts of the business are still viable, identify the most urgently required improvements, and determine where the company’s future growth lies. They must not only develop a strong plan—including potentially painful measures to restructure, sell, or close legacy businesses—but must also communicate this plan to their investors.

CEOs must develop a clear purpose for the change effort. At any given time, in this era of always-on transformation, companies have multiple initiatives underway, which can be exhausting for people in the organization as they cope with constant change. CEOs need to reenergize people with an explicit purpose—the “why” around which management and the rest of the organization can rally.

CEOs must adopt agile and digital methods to drive change. To get breakthrough results fast, while inspiring and engaging employees, leaders should adopt agile approaches—for example, mapping customer pain points, establishing cross-functional teams, and establishing new ways of working, such as two-week “sprints,” obstacle boards, and minimum viable products. At the same time, they must leverage digital technologies to improve the customer experience and simplify workflows. (See the sidebar “A Bank Transforms Through Agile and Digital.”)

A Bank Transforms Through Agile and Digital

The financial services industry is digitalizing, and consumers are interacting with their banks in new ways. One bank recently launched a multiyear transformation, starting with the appointment of a new CEO.

The transformation thus far has seen three phases: strategic focus by selling off noncore assets; reliable delivery on commitments to investors through tighter management of revenues, costs, and investments; and the rollout of new processes for consumers, capitalizing on digital and using the agile approach to speed the time to market. All cross-functional teams work in the same space and have a high degree of autonomy and decision-making authority during the product development process.

Rather than taking months or years, rollout of new services can be achieved in weeks, in part because the objective is to get a minimum viable product into the market as soon as possible. From that point, the development team can capture feedback and make rapid design iterations, improving the product.

The company has used several tools to make this happen:

- A 90-day countdown clock that pressures teams to deliver their projects on time

- A visual escalation board that impels action to clear project bottlenecks within 96 hours

- A wall of champions aimed at fostering a competitive spirit and celebrating successes

- An open-door policy that encourages employees to raise issues and express concerns

Through this program, which relies heavily on digital technology, the bank has dramatically accelerated the pace of standard customer processes. Opening a new account, which used to take nine days, now uses a digital approach and takes just 10 minutes. Business transactions that once took six days have been equally accelerated. A virtual self-service business assistant for business customers saves up to $16 million per year.

The program’s benefits include higher revenues (as much as 3% higher for selected initiatives), lower costs due to more streamlined and digitalized processes, and a superior customer experience with higher customer ratings and conversion levels. Moreover, because teams are now freed to move fast and deliver innovative new offerings, the transformation has enhanced employee satisfaction, engagement, and inspiration.

CEOs must assemble diverse leadership teams. Assembling the right senior executive team, a critical component of transformation success, is a challenge for some CEOs. The ideal team includes people from inside and outside the organization who understand the current core business, as well as the actions needed in order to respond to—or lead—disruptive change. It is important to strike the right balance between external hires (who can bring fresh ideas and new capabilities, particularly digital) and internal talent (who know the business and organization).

CEOs need to apply directive and inclusive leadership. Leaders cannot simply set the broad vision for a transformation and then delegate its execution. Instead, they must show directive leadership, setting the ambition, articulating strategic priorities, and holding management accountable for results. At the same time, they need to be inclusive, involving their teams early on, fostering collaboration, soliciting honest feedback, and empowering teams to define and implement specific initiatives. Striking this balance can be difficult, especially during the intense pressure of a major transformation effort.

Key Findings from the Analysis

In addition to our first-hand experience with transformations at large companies worldwide, we analyzed transformation programs at large US companies to determine key success factors. Our analysis focused on companies that had shown a dramatic decline in total shareholder return.

The findings offer some evidence-based guidance for new CEOs:

Virtually every company needs a transformation. Roughly one-third of the companies we analyzed had faced a sharp decline (more than 10 percentage points) in total shareholder return (TSR) over any two-year span. Within that subset, one-third had deteriorated even more over the following five years. The clear implication is that most companies need to transform at least once during any five-year window. And given the fact that transformations are multiple-year endeavors, they inevitably overlap.

Some predictable factors separate winners from losers. Some factors have a significant impact on the long-term results of a transformation. Specifically, companies that invest more in R&D and have a long-term strategic outlook are the most likely to post outsize gains in TSR following a transformation. This is partly because companies that deliver a cogent plan to investors gain credibility, which leads to higher expectations and valuation multiples. Similarly, hiring a new CEO, particularly one from outside the company, has a positive impact, and companies that have a formal transformation program in place—rather than a series of ad hoc improvements—perform best. (See Exhibit 1.) Moreover, these factors work together: building a transformation around all three aspects can increase a company’s long-term TSR by 13.5 percentage points.

In setting a long-term strategy, revenue growth is the biggest factor in transformation success. Meeting expectations in the early stages establishes credibility, and costs are important across all time periods. But over the long term, increases in sales have the greatest impact on shareholder value. A company can’t cut and trim its way to top-quartile performance. Transformation requires balancing the opposing aims of cost discipline and investment in the future. Notably, investments in capex do not automatically lead to improved performance. Instead, companies should aim to grow by spending on R&D with a clear link to sales growth. (See the sidebar “Carlsberg Saves $300 Million and Reinvests for Growth.”)

Carlsberg Saves $300 Million and Reinvests for Growth

Carlsberg, a 170-year-old global consumer goods company, had been stagnating for several years, owing to heavy debt and challenging market conditions. The company’s sales volumes were declining in several markets, and EBIT margins trailed behind those of its competitors.

In 2015, Cees ‘t Hart joined the company as CEO with a forceful idea of a strategic transformation aimed at restoring growth, focusing on premium products, and reorienting the company toward more attractive market segments. The company’s considerable debt burden complicated the challenge, but Hart addressed that by launching a comprehensive two-year program. The goal was to save approximately $300 million and reinvest half of that in strategic measures that would boost growth, employee engagement, and new capabilities.

The transformation had two key components to fund the journey. First, Carlsberg reduced costs by streamlining the organization, improving operations, and increasing the efficiency of production processes. Procurement measures led to additional savings, as did steps to reduce complexity. Next, the company boosted short-term revenue growth by adjusting its mix of products, optimizing revenue management, and applying a systematic lens to promotions.

In addition, Hart set out to reconnect with Carlsberg’s original purpose so that the organization could draw strength from its foundation and heritage.

This comprehensive approach allowed the company to reduce debt significantly, raise EBIT margins, and position itself to invest in the future. The share price shot up during the first two years, reaching an all-time high and—in terms of shareholder returns—beating Carlsberg’s main peers.

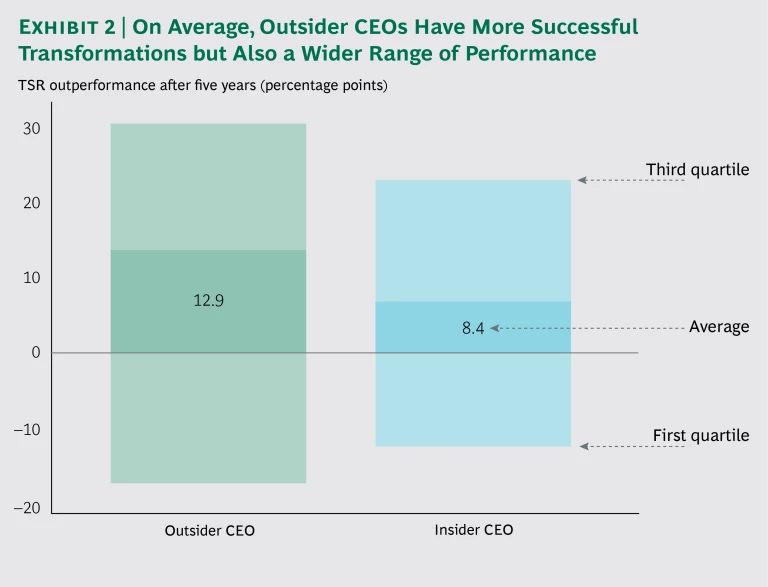

On average, new CEOs hired externally show better—but also greater variation in—performance than internal hires. Many outsider CEOs bring a new perspective to a company’s situation. Because they may not have much tied up in the success of previous approaches, they are more willing to make dramatic changes. As a result, outsider CEOs typically lead to better TSR than those hired internally. The caveat, however, is that the results of outsider CEOs also show greater variability. (See Exhibit 2.) These CEOs take big swings, which sometimes lead to home runs but can also lead to strikeouts. A company needs, therefore, to be mindful of the potential for variability if it is recruiting from outside the company.

Rapid action will be rewarded. Finally, new CEOs need to understand the urgency of their company’s situation and take rapid action. We have found that some new CEOs are cautious about taking quick action and hesitate to make changes that go deep enough to make a difference. Developing and communicating a clear plan to investors can establish the CEO’s credibility and lead to the biggest short-term difference in performance—an increase in the valuation multiple. The message for incoming leaders is clear: you must show compelling plans and take immediate action. By laying the groundwork in advance, you can be prepared to lead from the front with a clear vision, solid objectives, and the tools and processes to succeed.

A Four-Part Approach

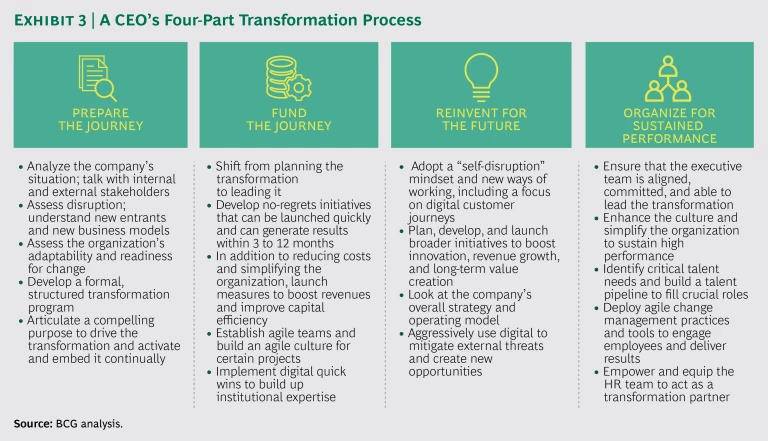

On the basis of our experience helping companies design and implement transformations, as well as the findings of our quantitative analysis, we have identified four transformation imperatives for new CEOs: prepare the journey, fund the journey, reinvent for the future, and organize for sustained performance. (See Exhibit 3.)

Prepare the Journey

Before a new CEO takes over, and during the first few weeks on the job, he or she needs to take charge, develop a clear-eyed view of the company’s current situation, and define the organization’s collective transformation ambition.

In defining this ambition, it is critically important for CEOs—whether hired from within or brought in from outside—to adopt an investigative and analytical mindset that says, “I need to learn more.” Incoming leaders should talk with as many critical stakeholders as possible, including employees, customers, and industry and functional experts, to educate themselves about the company. This also includes identifying and talking with new entrants and startups in the company’s business and adjacent businesses and offering speed and new alternative business models. Ideally, to be able to move quickly, a new CEO should gather the new leadership team even before getting started. Then, it’s important to establish a management meeting cadence and meet frequently to ensure that everybody is onboard.

Most important, the transformation should be structured as a formal program. Rather than business as usual or a few incremental measures, this program should bring profound change that has the potential to affect the entire organization and that aims to improve performance substantially. Such a program requires flexibility that allows leaders to revisit the plan and make adjustments on an ongoing basis.

During the initial weeks and months of a new CEO’s tenure, communication is critical for engaging and energizing the company. Leadership transitions and transformations can be stressful periods for any company, and undergoing both simultaneously doubles the pressure: employees must go above and beyond their regular responsibilities, working in unfamiliar—and even initially uncomfortable—ways. The always-on transformation makes this challenge even more difficult, because it removes the finish line. Accordingly, the CEO should articulate, activate, and embed a clear purpose for the work that the company does each day, establishing an explicit link that shows how the transformation supports that purpose. Our research has shown that companies with a strong and clear purpose deliver better financial performance over time. (See Purpose with the Power to Transform Your Organization , BCG Focus, May 2017.) One key reason for this is that bold action and clear communication can help establish credibility with investors and other stakeholders.

Fund the Journey

As the transformation starts to take shape and the case for change becomes clear, the CEO must shift gears from planning the transformation to actually leading it. This means immediately kicking off rapid, no-regrets moves—initiatives that are relatively easy to implement in the first 100 days and that can generate results in 3 to 12 months. These no-regrets initiatives should close performance gaps in a few critical areas, reduce costs, improve top- and bottom-line performance, and free up cash in order to fuel longer-term initiatives. (See the sidebar “A Chinese Industrial Goods Company Transforms Itself to Improve Operations.”)

A Chinese Industrial Goods Company Transforms Itself to Improve Operations

After a dramatic expansion, a Chinese industrial goods company needed an operational transformation to improve and standardize production. Several of its large plants were losing money on each ton of finished goods. The transformation program combined multiple no-regrets measures aimed at stabilizing the company’s situation and transforming the organization, including optimizing the product cost, reducing inventory, standardizing and improving key processes, and revamping services such as handling customer complaints. The program also included growth-oriented measures, such as the launch of new high-end products, more effective coordination among factories to optimize the product mix, and improvements to the customer mix.

At a later stage, the company launched a series of initiatives for building a long-term platform for success, including optimizing logistics and improving quality control.

As a result of the transformation, the company’s margins turned positive within two years, and it began to create value as it grew. More impressive, the company embedded the transformation measures into the daily activity of each plant, making the changes sustainable over time.

The primary levers for funding the journey are revenue increases, organizational simplicity (delayering), capital efficiency, and cost reduction. And digital applies across all four levers. In deciding where to start, many companies opt for the obvious solution: cost reduction. We have found that even though revenue and organizational simplicity measures can have an even faster impact, they are often overlooked.

With regard to digitalization, small-scale pilot tests and quick wins are crucial to kick-starting transformation: they build up institutional expertise, serve as proofs of concept, and build momentum for broader efforts. (See the sidebar “A Global Industrial Company Wins Through a Commercial Transformation Built Around Digital.”) Given the dynamic nature of business and the fact that transformations take years to implement, some traditional practices can no longer keep up. Long delivery cycles are no longer viable, especially as agile ways of working become more prevalent. Increasingly, leading companies are using agile methodologies to implement change. Done right, agile requires creating small, nimble, cross-functional teams that have been given a high degree of autonomy. These teams, which can move much faster than traditional organization structures, promote better output, shorter time to market, and higher satisfaction among employees and customers alike. (See “ Taking Agile Way Beyond Software, ” BCG article, July 2017.)

A Global Industrial Company Wins Through a Commercial Transformation Built Around Digital

A large industrial company launched a massive digital transformation aimed at increasing its efficiency and competing more effectively in markets whose producers have limited pricing power. The company did not want to tie up capital in a massive change program and wait years for a payback. To avoid that outcome, the company first identified a few quick-win initiatives that would pay off within a month or a quarter.

It first selected initiatives in inventory management and capacity optimization, analyzing output and shifting production to sites that were the most profitable. For these quick wins, the company used static data and created one-off solutions. But the projects led to significant savings and increasing sales of high-profit items, which generated immediate value.

Within nine months, these initiatives had generated $20 million in value. Once the projects that were based on static data were up and running, the company went back and built the systems it needed for managing these processes and functions continuously, using real-time data flows.

Applying lessons from its early wins, the company created a roadmap for ten major data transformation initiatives in areas such as demand forecasting and sales force management. The company also made plans for new, company-wide resources, including a data repository, that will support and sustain data-driven approaches. And it has begun to identify new data-driven business models.

The overall goal for the transformation is to unlock $200 million in value over three to five years and to help the company raise its EBITDA by 2% to 4%.

A new CEO must push hard to get things done. If the team is not performing, the new company leader shouldn’t hesitate to remove people quickly.

Reinvent for the Future

In parallel with initial fund-the-journey efforts, the CEO must launch broader initiatives to reinvent the company for the future and build sustainable performance with a focus on innovation, growth, and long-term value creation. Reinventing for the future can entail a wide range of initiatives to transform, including boosting growth, launching a new business model, revamping commercial processes or operations, building digital capabilities and ventures, and transforming critical processes, such as R&D, and internal support functions, such as IT and HR. (See the sidebar “Nokia Reprograms Itself for Growth.”)

Nokia Reprograms Itself for Growth

Nokia, which has transformed itself—in a range of industries and products—many times in its 150-year history, didn’t settle on phones and networking equipment until the 1980s, when mobile technology took off. In 2007, the company dominated in mobile phones, owning 40% of the global market, thanks to clearly superior technology and enormous advantages of scale. Just five years later, however, Nokia was in a severe crisis: market capitalization was 96% lower than it had been in 2007, it was burning cash, and its operating losses exceeded $2 billion in the first six months of 2012 alone.

In response, Nokia launched a dramatic, bet-the-company turnaround. The top strategic concern was the fate of its mobile phone business. In the war of the mobile ecosystems, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android were rapidly capturing larger and larger chunks of the smartphone market, and it seemed unlikely that Nokia’s Windows Phone strategy would be able to save the company. So Nokia decided to sell its mobile phone business to Microsoft and announced the divestment as part of a $7.2 billion deal in September 2013.

After the divestment, the new Nokia was essentially a portfolio of three fairly different businesses: network infrastructure, mapping services, and technology and patent licensing. This situation brought Nokia to its next big strategic decision. Should the company start to develop itself as a portfolio company or should it focus its activities?

Nokia’s largest remaining operational unit was the network business. But since 2007, Nokia had been operating its network infrastructure unit as a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens. And until 2013, Nokia had been planning to reduce its involvement in the business by preparing the joint venture for a full spinoff and IPO.

As a first move toward building a stronger presence in this industry, Nokia decided to take full control of this unit by buying out Siemens. Why? The joint venture agreement was coming to an end, and one of the parties would need to assume the full ownership—along with all the associated risks and rewards. Nokia’s move proved a success: over the next two years, the company successfully integrated the network unit as the new core of the corporation, generating several billion dollars in shareholder value.

However, the full extent of Nokia’s grand plan for the network infrastructure business was revealed only two years later. In 2015, Nokia announced its intent to acquire Alcatel-Lucent. With this industry-shaping $16.6 billion acquisition, Nokia expanded its business from being a provider of mobile network services to covering the full range of products and services in network infrastructure (such as IP routing and optical networks). Furthermore, it strengthened its presence in North America. During the same year, Nokia sharpened its focus by divesting its mapping business to a group of German car companies (including Audi, BMW, and Daimler) for $3 billion.

Despite its repositioning as a full-fledged network infrastructure provider, Nokia decided to retain its patent- and technology-licensing business in order to sustain its legacy of innovation and reinvention. In addition to holding the majority of Nokia’s patents, the unit today innovates in such areas as virtual reality and digital health. Although it accounted for less than 5% of Nokia’s 2016 revenues, the unit generated 22% of the operating profits and, according to analysts, an even higher share of the group valuation.

To understand how drastically Nokia has changed in the course of its journey, one can look at Nokia’s workforce. Since the start of the turnaround through early 2017, the company had turned over 99% of the employee base, 80% of the board, and all but one member of the executive team. Chairman Risto Siilasmaa, who took over in May 2012 at the height of Nokia’s troubles, described the journey: “It has been a complete removal of engines, the cabin, and the wings of an airplane and reassembling the airplane to look very different.”

This transformation—from walking dead to thriving in a new core business—won’t likely be Nokia’s last. But its success shows that the company can navigate massive disruptions, reorient itself, and come back ever stronger. Today, Nokia is once again the pride of Finland: the nation’s most valuable company, Nokia is well positioned for the next chapter in its long history.

In addition, while they are driving transformation initiatives, companies benefit from stepping back and reviewing their overall strategy and operating model. As discussed above, the best path to long-term value creation is a sharp focus on increasing revenues in the core business through targeted R&D investments that can unlock growth to fund future initiatives. (See the sidebar “A New CEO Transforms a Pharmaceutical Company.”)

A New CEO Transforms a Pharmaceutical Company

When a new CEO took over a large pharmaceutical business, he quickly realized that pressures in the health care industry, intensifying competition, and the company’s evolving product portfolio meant that the company would require a transformation.

Accordingly, the leadership team developed a new operating model configured to incorporate the following features:

- Customer interactions designed to optimize the patient experience

- An agile, technology-enabled infrastructure that frees resources for strategic investments

- A new HR strategy to improve employees’ engagement and better assess their performance

- Clear governance with minimal decision-making layers, particularly regarding the company’s R&D pipeline

- Greater transparency into the company’s deployment of resources to ensure that the focus remains on the products with the biggest potential impact

The transformation has meant dramatically improving financial performance and outpacing competitors in terms of shareholder value creation.

Digital technology is a crucial element of reinventing for the future. Disruptions to most industries are the result of new technology, and the attacks, which seem to arise from nowhere, progress very quickly. Companies need to stay ahead of this threat by disrupting themselves, taking an aggressive approach to implementing digital. Successfully integrating digital not only mitigates threats but also creates opportunities. New tools such as data analytics can dramatically improve a company’s financial and operational performance, and other tools open up new value streams.

Organize for Sustained Performance

Transformations are no longer one-time initiatives. Because the pace of change is so fast, companies need to adopt an always-on transformation mindset. Transformations require changing the way that the company operates and, consequently, assembling new talent and capabilities.

The CEO, in conjunction with the leadership team and HR, must determine how the transformation will affect its people, in particular through leadership and talent requirements, organization design changes, new capabilities that need to be developed, and changes in the culture. And this process needs to be at the core of the transformation plan from the beginning. This is not an issue that executives can address later in the process.

The imperatives of organizing for sustained performance include the following:

- Ensure that members of the leadership team are capable of heading the transformation in a way that is directive and inclusive. They need to set the appropriate priorities, make rapid, high-quality decisions, mobilize and energize initiative teams, engage the broader organization, and hold themselves accountable for the results.

- Adopt a people-first approach to change, deploying change management approaches, tools, and processes—including, for example, an activist project management office, agile ways of working, high-touch engagement, and digital “nudges”—to engage stakeholders and deliver results. (See “Digital-Era Change Runs on People Power,” BCG article, August 2017.)

- Enhance the culture, aligned with the company’s purpose, by determining which values and behaviors are required in the transformed organization, and take the actions required to reinforce these values and behaviors as a new way of working. This should happen in conjunction with actions that simplify the organization. Usually, this entails eliminating waste and low-value work, trimming bureaucracy, implementing shared services, automating processes, and enabling the organization to continue taking these steps on an ongoing basis. (See the sidebar “A Transformation Helps a Software Firm Become More Agile.”)

A Transformation Helps a Software Firm Become More Agile

As the market shifted to cloud and mobile offerings, a large software company with a strong legacy business was struggling to capitalize on new growth opportunities. The company’s new CEO, realizing that the culture—long a source of strength—might be holding it back, initiated a transformation to make the company more agile and innovative, without increasing costs.

The company launched an 18-month transformation that was based on a broad range of initiatives, including rethinking the portfolio, improving innovation, revamping the corporate function, speeding go-to-market processes, and developing the right talent to support new behaviors. It shifted investments dramatically from legacy to emerging businesses, and it introduced measures to reduce operational costs.

A C-suite-level transformation office, led by the CEO, regularly communicated with project teams to define clear solutions and secure the board’s quick approval to expedite and accelerate the progress of ideas from creation to implementation.

The payoff was dramatic: the company identified more than $1 billion in annual cost reductions that it redeployed to high-priority businesses, innovations, and shareholder returns. Furthermore, it emerged with a new engineering model for getting products and services from the design stage to customers rapidly. An improved culture also prioritized innovation while retaining the critical subcultures within certain business lines and functions that employees prized. In all, the company became far more agile and responsive, allowing it to regain its position as a technology market leader.

- Identify talent needs and build a pipeline that can help fill crucial roles, along with developing capabilities in areas critical to the transformation, such as digital, innovation, agile, go-to-market strategies, pricing, sourcing, and lean methods.

- Empower and equip the HR team to act as a transformation partner that anticipates and addresses leadership and talent needs, supports organization redesign, and partners with leaders to develop the culture.

Even large and successful companies need to transform themselves in response to current or looming threats. CEOs need to adopt a mindset of restlessness and continuous change. By following a clear methodology for transformation, starting even before the first day on the job, a new CEO can take the steps needed to make the company more adaptive and responsive, putting it on the right trajectory for success. The best response to external disruption is not playing defense. Rather it is embracing preemptive self-disruption.