Diplomatic ties between the US and Cuba have been improving over the past several years, and interest has soared among US citizens who want to travel to the once-forbidden island. The Boston Consulting Group estimates that by 2025, as many as 2 million US travelers could visit Cuba each year, hoping to experience one of the last authentic Caribbean destinations before it modernizes. However, some skeptics have recently started to question whether this boom will last. After a huge initial expansion, some US airlines have scaled back several routes to Cuba, and a couple have withdrawn completely, raising questions about US travelers’ interest in Cuba and whether it will translate into action.

In addition, with its severely outdated infrastructure, Cuba is already struggling to handle the current level of visitors, some of whom have returned to the US less than enthusiastic. The country’s main international airport, in Havana, is bursting at the seams, and because there is an insufficient supply of accommodations, room rates have climbed far above the Caribbean average. Basic processes, such as accessing cash, are difficult, and many Cuban tourism venues have not yet established the kind of customer service mindset that US travelers take for granted.

The reality is that US travel to Cuba is in its nascent stages, and all the players are still learning how to make it work. Success, as with most things Cuban, will require unusual—and often unorthodox—approaches. Airlines, hotels, and cruise lines will need to develop their understanding of demand and how to stimulate it, as well as how to operate in a centrally controlled country that is suffering from years of underinvestment. And Cuba’s authorities will need to quickly invest in the country’s infrastructure to ensure that Cuba can capitalize on this wave of interest and avoid letting a once-in-a-generation opportunity pass by.

Travel Restrictions Ease

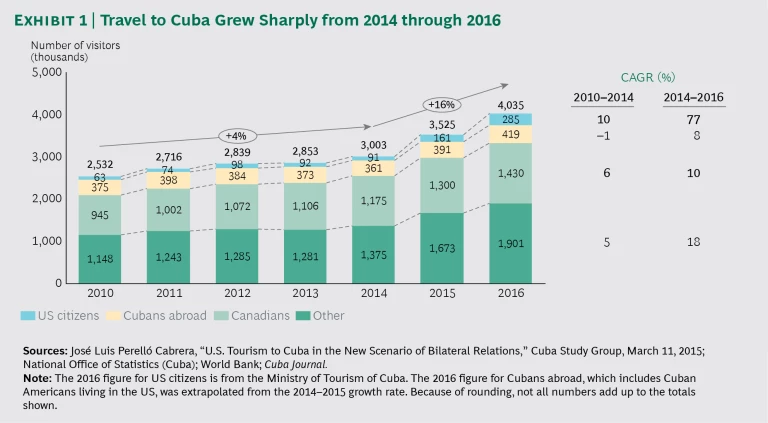

Having hosted more than 4 million travelers in 2016, Cuba is already the third-most-visited destination in the Caribbean—behind the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Most of Cuba’s visitors come from countries other than the US, including roughly 1.4 million Canadians. US numbers have been low owing to heavy restrictions imposed by the US government.

For decades, US citizens could get visas to Cuba only if they met certain conditions—if, for example, they were doing missionary work or traveling as part of a cultural exchange. Those restrictions have eased significantly in the past two years, thanks to efforts by both the US and Cuban governments, and rather than needing to book trips as part of a group, individuals can now make their own travel arrangements. Technically, however, traditional tourism from the US is still not allowed.

The two countries recently signed an agreement restoring air travel between the US and Cuba. American Airlines, Southwest Airlines, JetBlue Airways, and five other carriers currently operate round-trip flights between Cuba and the US. Similarly, the US has granted licenses for both cruise lines and ferry operations from the US to Cuba. When Carnival Cruise Line’s Fathom brand docked a ship in Havana in 2016, it was the first from a US port in more than 50 years.

In all, 285,000 US citizens traveled to Cuba in 2016 (not counting Cuban Americans). That’s three times the number in 2014, before the travel restrictions were eased. The number of travelers from other countries has grown as well. (See Exhibit 1.)

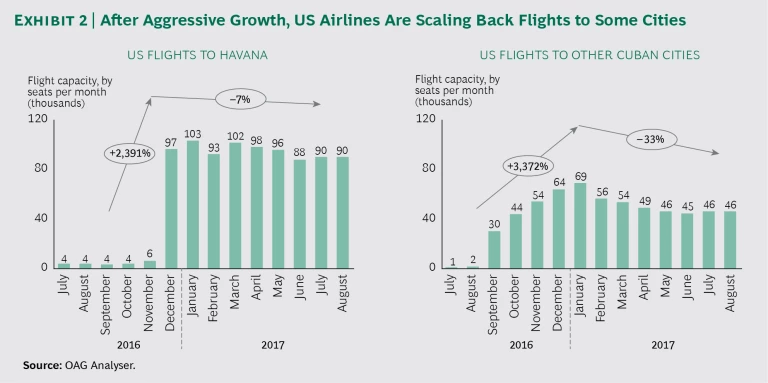

Now, however, after that initial rush, the media are running stories hinting that Cuban tourism is a bust. Airlines are reducing capacity, some withdrawing completely, and one cruise line has already pulled out of the market.

Boom or Bust?

To understand the actual demand from US travelers in such a dynamic market, BCG recently surveyed 500 US travelers—those who had been to Cuba and those considering such a trip—in late 2015 and again in late 2016. We also interviewed Cuban tourism experts, and we traveled to the country to assess its tourist infrastructure firsthand.

Our research confirms that there is strong and growing interest among US travelers. We project compound annual growth rates of 20% to 50% in the number of US visitors to Cuba through 2020. And it’s quite possible that more than 2 million US citizens will be visiting the island annually by 2025.

Key findings from the research include the following:

- Among US travelers, demand is strong and will grow over the next three years. In 2016, 30% of survey respondents expressed interest in visiting Cuba—an increase over the prior year—and more than 80% of them said that they want to go within the next three years. Of this group, roughly one-third said that they want to experience the country before US visitors have a major impact, and 23% want to see what life is like under a different political system.

- The demand is highly concentrated in Havana. Cuba’s capital city, cited by 80% of respondents as their first choice, is the most popular destination. This is not only because of Havana’s rich history and culture but also because it is one of the few areas in Cuba that US citizens know about. Interest in other cities is low: less than 10% of respondents expressed interest in cities such as Camagüey, Holguín, or Matanzas.

- Cuba may draw US travelers away from other Caribbean destinations. Some 60% of respondents said that they would skip a trip to the Dominican Republic or the Virgin Islands in favor of Cuba, and more than 50% said that they would skip a trip to Mexico or the Bahamas. For companies that operate across the region, there is a risk of cannibalizing sales from one area for another. In addition, countries in the region recognize the heightened competition from Cuba and are taking steps in response. For example, Jamaica’s government announced that it would work with the cruise industry to establish Jamaica-Cuba itineraries.

- Travel companies are still determining the right level of supply. US airlines quickly snapped up the allocated daily US-to-Cuba flights before they had a clear idea of demand. Within a few months, capacity had increased by a factor of nearly 30 to about 2 million seats each year, with 40% going to destinations outside Havana. Even with the surge in US interest, we estimate that this is at least double the capacity needed to satisfy demand in 2017 and closer to what is projected for 2025. Predictably enough, airlines are scaling back capacity, especially to second-tier cities outside Havana—even as flights between Miami and Havana are full. (See Exhibit 2.)

As for cruise lines, our research suggests that interest is strong: nearly 40% of survey respondents who had not taken a cruise in the past said that they would consider one to Cuba within the next five years. Among those who had taken a cruise, the numbers are even more favorable: nearly two-thirds would consider a cruise to Cuba. Cruise lines recognize this, which is why they are increasing the number of itineraries with stops in Cuba.

Tourism Infrastructure Lags Behind

A recurring theme among survey respondents was the fear that Cuba could soon become Americanized and indistinguishable from other tourist destinations. On the basis of our firsthand travel experience in Cuba, we are quite certain that Americanization is not likely in the immediate future. In fact, the bigger challenge lies in trying to accommodate the growth in US tourism.

Cuba is still a Communist-run, centrally controlled economy, and it is suffering from decades of underinvestment in infrastructure. Cuba’s government recognizes the importance of tourism in growing the country’s economy, and it is actively trying to improve its travel infrastructure while preserving the island’s cultural heritage.

To stimulate the economy, the government has developed a list of priority projects, including 114 in the tourism industry. In addition to hotels, the list includes other infrastructure, such as marinas for sailboat charters and golf courses. The government is seeking foreign investors for these projects as a way of accessing international capital and stimulating tourism.

Road travel is not easy. Most roads in Cuba are poorly maintained, and potholes mar even the main highways. Road signs, roadside assistance, and amenities are almost nonexistent, making it difficult to navigate the country. Some car rental companies (such as Europcar) operate in Cuba, but inventory is limited, with cars usually fully booked months in advance. Furthermore, buses, too, are often fully booked, making it difficult for travelers to see more than one city on their own.

Basic tourism services are unreliable. Simple activities such as booking a hotel room on the island, making mobile calls, using the internet, and accessing cash can be unnecessarily cumbersome—at times, impossible. Travelers need to bring hard currency and convert it once they arrive.

Cuba is only beginning to develop a customer service mindset. One of the biggest problems is the lack of a hospitality mindset at facilities run by the state. (Even US companies are required to hire through a government agency.) The government operates most of the country’s tourist infrastructure—airports, hotels, buses, and ports—and it pays Cuban employees a fairly low standard wage of about $20 per month. There is little incentive to work hard, and the lapses in customer service are notable. For example, hotels struggle to get rooms cleaned by check-in time for the new guests. Some US travelers seeking a relaxing vacation find that Cuba falls short of their expectations, and they are reporting this in their reviews on TripAdvisor and other social media websites.

However, the growth of entrepreneurs—cuentapropistas—in the travel sector should improve the service aspect in Cuba. Cuentapropistas acting as tour guides or running restaurants or de facto B&Bs may experience an uptick in business (and tips) for offering good service or a decline (and low ratings online) for bad service.

Key Takeaways for US Travel Companies

Our research points to specific priorities for US airlines, cruise lines, and hotel companies.

Airlines must deal with an imbalance in demand for Cuban destinations. Havana’s visitors currently account for nearly 60% of the island’s weekly flight capacity from the US, and José Martí International Airport in Havana is already struggling to service the current volume. US carriers now have access to a larger and more modern international terminal, though delays are still common.

Accordingly, airlines could address this imbalance in demand with marketing campaigns aimed at educating US travelers about Cuba’s lesser-known cities. (Because so many US residents want to visit Cuba before it becomes modernized, the authenticity of smaller cities could be a selling point.) However, given the current restrictions, tourism-based marketing could be difficult.

US airlines could also try to capitalize on growing outbound demand from Cubans who live in these cities and wish to visit the US. Cuba’s government has relaxed some of the restrictions that have prevented Cubans from traveling abroad, so as the base of potential Cuban air travelers grows, airlines could tap into that opportunity by marketing themselves inside Cuba. To that end, in fact, American Airlines recently opened an office in Havana.

Cruise lines must address infrastructure constraints in port cities. Cruise lines provide the easiest way to travel to Cuba: transportation, food, and lodging are all prearranged. The port in Havana can currently handle midsize cruise ships. However, there are other infrastructure problems. Given that Cuba experiences food shortages for its own citizens, getting meals in port cities is a challenge. In addition, US travelers still need to visit Cuba as part of a cultural exchange rather than simply as tourists. That means that port visits must include a cultural element delivered to one-day influxes of approximately 2,000 people, which poses another challenge.

The solution will likely require cruise lines to work more directly with Cuba’s Ministry of Tourism. Specifically, cruise lines will need to ensure that destination cities have enough food and other stock on hand to meet the needs of their passengers making port calls and that operators in those cities can deliver a culturally relevant experience that complies with the US government’s visa rules. Getting this right early on is critical. The people currently taking cruises to Cuba are early adopters, and their recommendations carry weight.

Hotel companies must increase capacity and improve customer service. There is already a shortage of hotel rooms in Cuba, and as demand increases, the situation will likely get worse—particularly in high-volume destinations such as Havana. Recently, there have been many reports of travelers unable to find accommodations. Furthermore, the small number of rooms that are on the market are extremely expensive for the region—the equivalent of $500 or more per night, even at outdated hotels. The problem is so acute in Havana—even showing up on trip reviews posted on social media websites—that Cuba’s Ministry of Tourism recently took steps to lower hotel rates in the city. (Such a measure is possible only in a centrally controlled economy.)

Casas particulares, rooms rented by homeowners, are filling some of the gap. Airbnb was among the first US companies to begin operating in Cuba after travel restrictions eased, further increasing the number of options available to travelers. However, it’s unlikely that those options will satisfy the demand, given that 86% of US travelers prefer to stay in hotels and resorts rather than private homes, according to our survey.

The government has multiple projects underway, primarily through partnerships with foreign companies, to double the island’s hotel capacity by 2030. For example, several Spanish companies have formed joint ventures to develop high-end, all-inclusive beachfront resorts in Varadero, several hours from Havana by car. (In the Dominican Republic, Punta Cana has a similar cluster of resorts.) In addition, hotel companies have begun to show interest. Starwood Hotels & Resorts, which is investing in and converting three Cuban hotels into Starwood properties, is the first US hotel company to operate on the island since the revolution in 1959.

Additionally, hotel operators may struggle to establish the right customer service standards for their properties. As noted above, the majority of workers in Cuba’s tourism industry—even those at US-owned companies—are employees of the state government. And although the economics of operating in Cuba are attractive—because of the low and controlled labor costs—instilling a hospitality mindset in these employees may be challenging. The risk is that US travelers who visit Cuba and stay at a hotel that is part of a brand they trust will experience prices much higher than usual—and poor customer service. Hotels will also need to address challenges related to bookings (reservation systems are not linked to global networks) and payments (US credit cards don’t work on the island).

As with cruise lines, hotels will need to collaborate with the Cuban government to figure out operational workarounds for some of these issues. As the country’s tourism industry matures, creativity and flexibility will be paramount to make sure that guests have a superlative experience.

Cuba represents a huge opportunity for travel companies, but success will not be achieved easily. Companies that accurately understand demand, take the steps needed to operate in a centrally controlled economy, and invest for the long term will likely be rewarded.