In the face of industry disruption, company owners focus on two questions: How will the company navigate the changes taking place? And what should business look like on the far side of the storm? Disruption upends not only markets and models but also the paradigms within which companies operate. Traditional goals for stable times, such as near-term EPS growth, are rendered irrelevant. Management teams need to shift gears, think like owners, and apply the fundamental tools of value creation with a reinvention mindset.

The 2017 Value Creators

When Disruption Your Way Comes

There are plenty of causes of disruption today—market shifts, technology advances, regulatory changes, and fluid trade policies, for example—and few industries are immune. Digital technology alone has upended multiple industries in recent years, and its impact is only beginning to be felt in others. Newer technologies such as artificial intelligence, augmented and virtual reality , and blockchain are gaining traction. According to CB Insights, some 215 “unicorns” (startups valued at $1 billion or more) are active in more than 20 industries today. More and more publicly held insurgents have surpassed incumbents in value and are appearing regularly at the top of our value creator rankings. The advent of fast-moving and powerfully backed insurgents is a strong signal for incumbents to take a hard look at the likely future of their current models and portfolios.

To continue to outperform in disruptive times, leaders must change their strategies, portfolios, and sometimes their business models. But radical reinvention—revamping portfolios and rethinking how companies compete and how they create value for their shareholders—is a tall order. Most companies are not used to reinventing their business models. And because established organizations are often hardwired to deny the need for disruptive change, they resist business models that upset the status quo.

As a result of these “reinvention barriers,” the odds against successful transformation in the face of disruption are really long—only about one in three companies emerges successfully. More important, though, is that the companies that do make the transition often create even more value than they did previously—an average of 14 additional percentage points of annual TSR than their peers. (See “ Creating Value from Disruption (While Others Disappear) ,” BCG article, September 2017.)

The Rules of Value Creation Still Apply

The same best-practice value creation tools that have been successful in stable times can be even more important in disruptive circumstances. They provide invaluable focus and insights into how to navigate the changes taking place. They can also guide priority setting, from a long-term investor’s point of view, for the reinvention program.

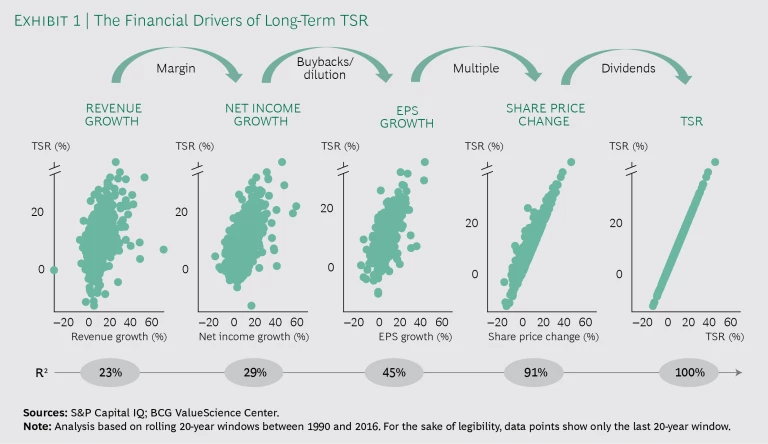

In relatively stable business environments, sustaining value creators do four things to consistently deliver superior results. First, they focus explicitly on the goal of TSR relative to their peers (rTSR) over a period longer than the current year (usually three to five years). Second, they make use of all the financial drivers of TSR—revenue growth, maintenance or expansion of profit margins, generation and allocation of free cash flow, and the management-controlled factors affecting their P/E multiple—and they reassess the priority assigned to each as times change. (See Exhibit 1.)

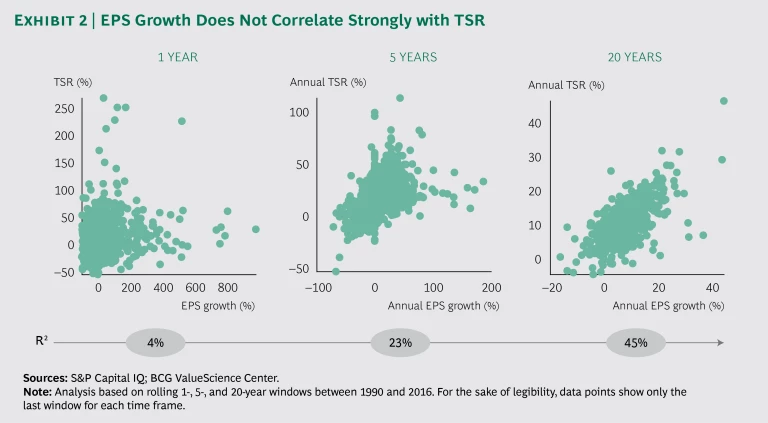

Third, they avoid using simplistic proxies for TSR success, such as managing quarterly or annual EPS growth, which in fact do not correlate strongly with TSR, even over longer time frames, and can be subject to manipulation or gaming. (See Exhibit 2 and the sidebar, “The Rules of Best-Practice TSR Management.”)

Fourth, they recognize the need to continually reexamine and periodically realign their business, financial, and investor strategies and priorities as part of the ongoing corporate strategy process.

The Rules of Best-Practice TSR Management

The Rules of Best-Practice TSR Management

The right governance focus in both stable and disruptive times is rTSR success. There are four reasons.

First, rTSR is objective. The P/E multiple component puts the market in charge. Investors can evaluate not only earnings growth and earnings performance versus expectations, they can also assess the quality of the earnings and whether the underlying cash flow is sustainable. That said, our research in multiple sectors has shown that 80% of the factors that drive a company’s multiple relative to its peers (which is what counts from a rTSR perspective) are largely under management’s control. (See the exhibit “More Than 80% of the Factors Affecting Valuation Multiple Can Be Quantified and Measured.”)

Second, the market is efficient. It has proven itself very good at reflecting all the known factors affecting a company and its performance in the company’s stock price. Investors collectively do not leave value on the table. This creates a level playing field for all companies to compete in delivering superior rTSR looking forward—no one is advantaged or disadvantaged owing to past performance. It’s all about future performance improvements and/or continuing to beat the fade that is baked into market expectations for most companies.

Third, rTSR corrects for macroeconomic and broad industry trends and events that are beyond management’s control. In this way, the metric reflects the value that management, through strategy, planning, and execution, adds to (or subtracts from) the enterprise.

Finally, rTSR is the only thing that matters to the investors that own a company. They may have different priorities for how superior rTSR is achieved (a growth focus versus a cash generation and payout focus), but in the end, rTSR success is what will keep them invested and supportive of management’s agenda.

An explicit rTSR governance focus needs to be based on a clear understanding of just how difficult it is to continuously win the rTSR competition with a company’s peers. Our analysis of the S&P 500, as well as of many specific industry sectors, shows that the odds of delivering above-average rTSR year in and year out are similar to a random coin toss: 50% in one period, 25% for two periods in a row, 12.5% for three periods in a row. These odds hold true even for top performers, because the valuation multiple component means that they typically revert back to average TSR over time. (See the exhibit “TSR Reverts to the Mean, Limiting Even Top Performers’ Upside.”)

For this reason, strategic plans should always be developed with an eye to winning on rTSR over the next three- to five-year period (and not every year in the period). Moreover, incentive program payouts should be based on realistic assessments of the frequency of delivering above-average rTSR and on the level and period of outperformance required to trigger a top incentive award. For example, delivering top-quartile TSR over five years typically requires performing 10 percentage points above the industry median, while delivering top-quartile TSR over a 20-year period typically requires only about a 4 percentage-point spread over the median.

In times of actual or potential disruption, companies need a governance objective to guide their reinvention toward a winning outcome and provide the discipline to stay the course, since disruption is by definition distracting. The rTSR metric, both relative to the market and relative to peers, provides such a goal. The rTSR best-practice management tools described above will provide a leg up in both navigating disruption and delivering ongoing superior value creation relative to peers. More traditional objectives, such as steady EPS growth, an increasing dividend, or revenue growth at a “served-market plus” rate, are likely to be no longer relevant—or even feasible—at least in the short term. All that counts in disruptive times—and all that executives can fully manage—is rTSR compared with the peers that are subject to the same disruptive challenges or opportunities.

One of the biggest drivers of rTSR success is likely to be what happens to each company’s P/E multiple given how investors perceive who the future winner(s) will be. Managing cash flow will also be more critical than trying to prop up EPS growth through creative accounting, share repurchases, or expense reduction when the underlying people or capabilities may be needed to meet the disruption challenge.

The experience of two tech companies—Adobe and Microsoft—illustrates the power of a focus on rTSR during disruptions. Adobe is one of only nine companies to have consistently outperformed over the past 20 years, with an annualized TSR of 16.8% from 1996 through 2016, compared with a median of about 10% for all the companies in BCG’s value creation database and 11.5% for the tech sector. And during that period, it undertook a major transformation of its business model. (See “ How Top Value Creators Outpace the Market—for Decades ,” BCG article, July 2017.)

Over the past five years, Adobe has posted an annualized TSR of 29.5% (number 11 among all large-cap companies), compared with 16.1% for the overall database and 18.4% for the tech sector. Microsoft, which has also undergone significant business model transformation, isn’t far behind, with 22.4% annual TSR over the past five years. The key reason for both companies’ strong TSR performance is the much-improved quality of their earnings, rather than their quantity, which highlights the benefits of their transformations. Adobe’s EPS has grown by only 6.7% a year over the past five years, compared with 8.2% on average for tech companies. Microsoft’s EPS even contracted by 5% a year over the same period. At the same time, both companies’ trailing P/E multiples have expanded by more than 20% a year (from as low as 9.3x to 28.8x for Microsoft and from 16.7x to 43.8x for Adobe), reflecting investors’ positive reaction to the moves both management teams are making.

Companies facing disruption will also need to rethink the alignment of their business, financial, and investor strategy priorities. Legacy capital allocation priorities can be either strained by disruption, become barriers to confronting disruption, or both. But while rethinking the business strategy is an obvious high priority, it can’t be divorced from developing and communicating a clear value proposition to the kind of investors who will support management—and the company’s P/E—during the disruption period or from developing a revised set of financial policies that reduce risk, preserve flexibility, and provide confidence to the market that the changes underway will work.

When disruption is not occurring but the cloud is on the horizon, the rTSR metric provides an early-warning signal that can help top management mobilize its organizations and boards. Companies should monitor the rTSR of their peer group versus the overall market as a routine exercise. When the peer group is underperforming the market (and the cause is not normal industry cyclicality), it may be a signal of impending disruption from a source such as regulatory change, new technology, or demographic shifts. When the peer group is underperforming the market and the company is underperforming its peers, that is an even stronger signal that reinvention is needed.

We examined the performance of 1,952 companies that attracted attention from activist investors from 2000 through 2017. These activist targets underperformed both the S&P 500 and their industry indices by more than 7 percentage points in the year before the activist arrived. They underperformed the S&P 500 by more than 3 percentage points, and the industry index by almost 6 percentage points, in the three years prior. Given a market and typical industry average TSR of about 9%, a 3 to 7 percentage-point gap is a clear call to action.

BCG has studied the patterns and drivers of rTSR success for almost three decades. In stable times, as well as in times of financial crisis, recession, technology change, or disruption, companies that win combine a willingness to embrace reinvention with the guidance and discipline of best-practice TSR management.